Experimental Art in Service to (East German) Society: Angela Hampel and Steffen Fischer’s Fluß-Uferzone, 1988

Art does not simply reflect a given social situation; as a creative act, it also works upon society to change it.

– Peter H. Feist1

When Peter H. Feist delivered his speech in Munich in November 1964, the art world in East Germany was in the midst of a multi-year thaw in cultural policy following the building of the Berlin Wall three years earlier. Freezes and thaws in cultural policy—between a Soviet-inspired socialist realism and a more modern one—were a hallmark of East German art throughout the Ulbricht era (1949–71), often in response to major political events.2 By the time Erich Honecker came to power in 1971, however, policy had largely settled into a permanent thaw, which he then cemented with a speech that December in which he stated that there would be no more taboos in art, neither in content nor in style, for those who believed in socialism.3 This commitment to socialism was an important caveat because criticisms of the government or the Soviet Union could still cause problems, but otherwise, artists working in traditional media such as painting, graphics, and sculpture were now relatively free to pursue their interests, including abstraction.4

This greater freedom for artists in the Honecker era did not include newer art forms, however, such as installations and performance art, which did not yet exist in East Germany at the time that Honecker gave his speech. Artists who began to experiment in these areas in the latter half of the 1970s thus often faced greater challenges than those working in traditional media. And yet, by the late 1970s, such works were not only created, they were also exhibited in official venues. In Dresden in 1979, for example, a group of artists in their twenties created an exhibition of installations at the Leonhardi Museum to mark the thirtieth anniversary of the country’s founding.5 Although controversial, this exhibition—known colloquially as the “Doors” exhibition because the artists incorporated doors into their work—had a “huge audience response” across its two-week run, with visitors coming from nearly all districts of the German Democratic Republic (GDR, or East Germany) as well as neighboring states, including West Germany.6 The exhibition sparked so much interest, in fact, that Willi Sitte, the then 59-year-old president of the national Artists’ Union (Verband Bildender Künstler, or VBK), felt compelled to comment upon the “commotion” (Rummel) of such “stupidities” (Dummheiten) in a speech he gave at the March 1980 meeting of the Artists’ Union’s central committee, stating that the artists at the Leonhardi Museum had stepped over a line (Grenze).7 A few years later, in November 1983, he made similarly disparaging comments about performance art at the VBK’s Ninth Congress, stating there would never be a section for it in the Artists’ Union as long as he was president.8

It is presumably Sitte’s hostility to experimental art, combined with the fact that he remained president of the Artists’ Union until late November 1988, that has led some Anglo-American scholars to claim—incorrectly—that installation and performance art “were officially banned until 1988.”9 German scholarship, on the other hand, has tended to focus on East Germany’s experimental scene in recent years.10 The story told by these scholars has created a new canon that includes the artists around the gallery Clara Mosch in Karl-Marx-Stadt (today Chemnitz), the Herbstsalon (Fall Salon) artists in Leipzig, the Intermedia Festival in Coswig, the Auto-Perforation Artists in Dresden and Berlin, and the Permanent Art Conference in Berlin.11 These scholars tend to emphasize the problems experimental artists faced and to gloss over or ignore the connections they had to the official art world, such as the fact that almost all were members of the Artists’ Union. Indeed, many of their exhibitions and events were held in official venues.12 Instead, the implication of much recent scholarship is that such works were made on the margins of East German society and by artists who were aloof from, if not hostile to, the ideals and values of the GDR.13 It is a narrative that confirms Western ideological investments in a negative view of socialism and a heroic view of artists who “defied” repression.14 It also reflects the personal interests of several of the most prominent authors on the topic, who had themselves been part of the art scene about which they are writing.15

This dominant view of installation and performance art in East Germany, however, tends to ignore important artists, works, and exhibitions that challenge the narrative of oppression.16 In this article, I will focus on two such artists—Angela Hampel (born 1956) and Steffen Fischer (born 1954)—and an artwork they created together in 1988 for an exhibition in Dresden titled Blue Wonder (Blaues Wunder).17 Although both had created and exhibited installations in public venues before this point, this exhibition marks the beginning of experimental art’s official acceptance and support by the Artists’ Union, a fact commented upon at the time by art historians at the national level. In its wake, experimental art was included in district art exhibitions and would likely have been part of the next national Art Exhibition of the GDR in 1992 had the GDR still existed. This is not to say that artists working in experimental media did not face challenges in the GDR, but rather to complicate the narrative.

Despite the importance of the Blue Wonder exhibition in the history of East German art, it is largely absent from current scholarship, presumably because it contradicts current accounts.18 Many of the artists in the exhibition, including Hampel and Fischer, for example, were not marginal figures in the East German art world. Rather, they exhibited regularly and were actively engaged in the Artists’ Union. Indeed, Hampel had catapulted into the national spotlight three years earlier for her punk-inspired Neoexpressionist images of strong women from mythology and the Bible, such as Judith, Medea, and Salome, and was highly praised for them on both sides of the Berlin Wall.19 Nor did they reject socialism: both artists viewed the GDR as the better Germany, albeit in need of reform.20 As Hampel stated in 2015, she did not want to overthrow the State; she “wanted to improve it.”21 Fischer also believed in the idea of “improving socialism,” although he was less engaged in the process than Hampel, who gave critical speeches at a number of Artists’ Union conferences.22 A closer look at their work in the Blue Wonder exhibition thus not only recovers an important experimental work by two previously well-known East German artists, it also reveals some of the problems and limitations of current scholarship, which tends to suffer from both a western bias and a presentist perspective.

The Blue Wonder exhibition

Acknowledged at the time as the first major Artists’ Union exhibition in East Germany to include installation art, the Blue Wonder exhibition was held from July 22 until August 14, 1988, in Fucik Hall A in Dresden, a large exhibition space just east of the city’s center that was also used for East Germany’s prestigious National Art Exhibition.23 Intended as a showcase of Dresden’s youngest artists, those under 35 or who had become candidates or members of the Artists’ Union since the last such exhibition of young artists in Dresden in 1981, it was organized by the Dresden branches of the Artists’ Union and the District Council, although it was the young artists themselves who chose the theme and organized the space.24

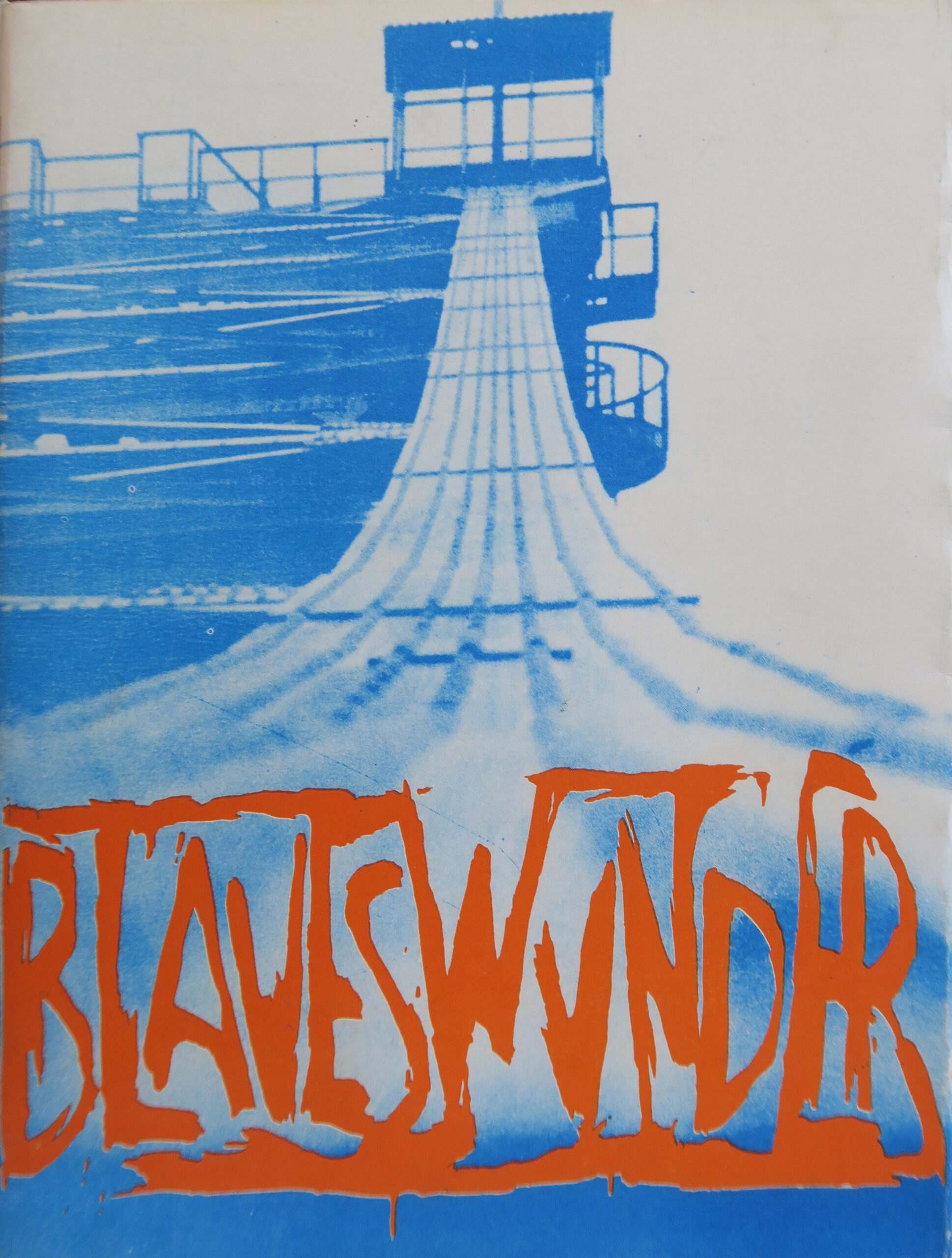

The exhibition was named after the scenic cantilever iron bridge that connects the eastern Dresden suburbs of Blasewitz on the south side of the Elbe River with Loschwitz on the north, where many artists lived. Considered a technological marvel when completed in 1893, the Loschwitz Bridge was soon nicknamed the “Blue Wonder,” in part because of the color of paint used on its surface. It later proved its name by surviving the Second World War relatively unscathed because, in this case, locals had prevented the Nazis from blowing it up as they retreated. As such, the Blue Wonder is an iconic symbol of Dresden and a more modern one than any of the buildings in the Altstadt (the historic part of the city). The artists chose “Blue Wonder” as their title, in part, to make clear their connection to the city, and displayed it prominently on the cover of the exhibition catalog, which depicts a sharply angled detail of the bridge (Fig. 1) with the title expressively written in deep orange along the bottom edge.25

The exhibition contained 368 works by 123 artists in a wide variety of media: painting, graphics, sculpture, arts and crafts, and design.26 There were also five installations, a fact frequently mentioned in the press at the time. The prominent East German art historian Lothar Lang, for example, published an article in the national journal Weltbühne (World Stage) in which he called the exhibition “admirable,” an “‘eye-popping event’ if for no other reason than because it is the first time that object art, previously taboo in this country, has been placed at the fore.”27 With a few exceptions, he noted, such as the Leipzig Herbstsalon in 1984, it was “the first major attempt to integrate object art […] into an exhibition on an equal footing with other genres.”28

In this context, the artists’ choice of the title of their exhibition may have referred to more than just the iconic bridge. In German, to experience a “blue wonder” is to have the shock of one’s life. Such a title was thus also a provocation, one fitting for a group of young artists wanting to make their mark in the art world and doing so by including works that had not previously been allowed in major Artists’ Union exhibitions.

Fluß-Uferzone

One of the largest and most discussed of the installations in the exhibition was Fluß-Uferzone (River-Shore), created by Angela Hampel and Steffen Fischer, two artists who had graduated from the Dresden Academy of Fine Arts in 1982 and became full members of the Artists’ Union in 1985 after completing the mandatory three-year candidacy period.29 Known for creating Neoexpressionist prints and paintings, the two had worked together on a number of projects before creating Fluß-Uferzone, including two murals and an exhibition of installations at the Galerie Nord that had closed earlier that year.30 Both were also active members of the Dresden art scene.

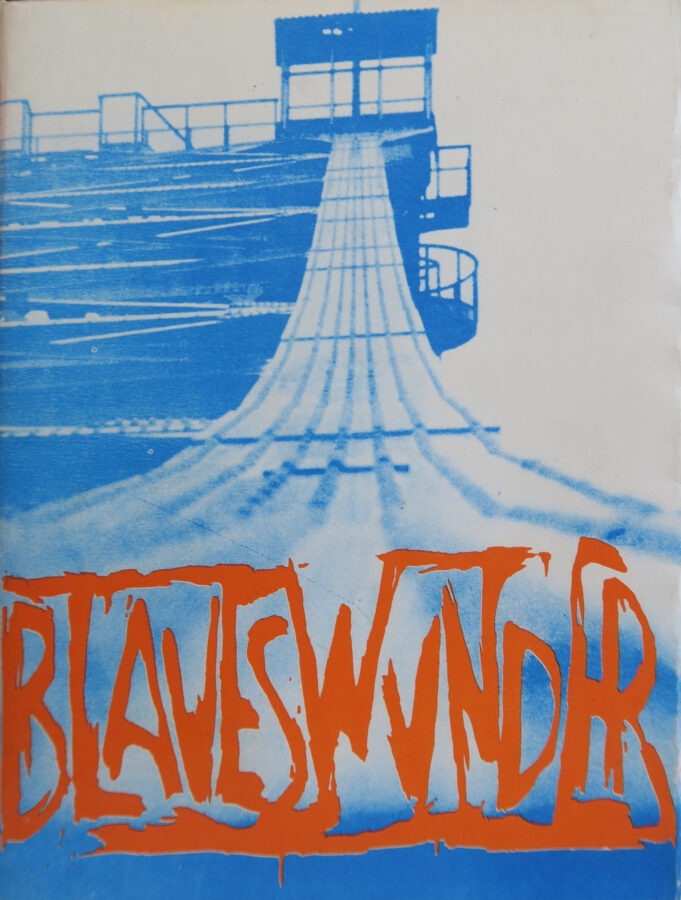

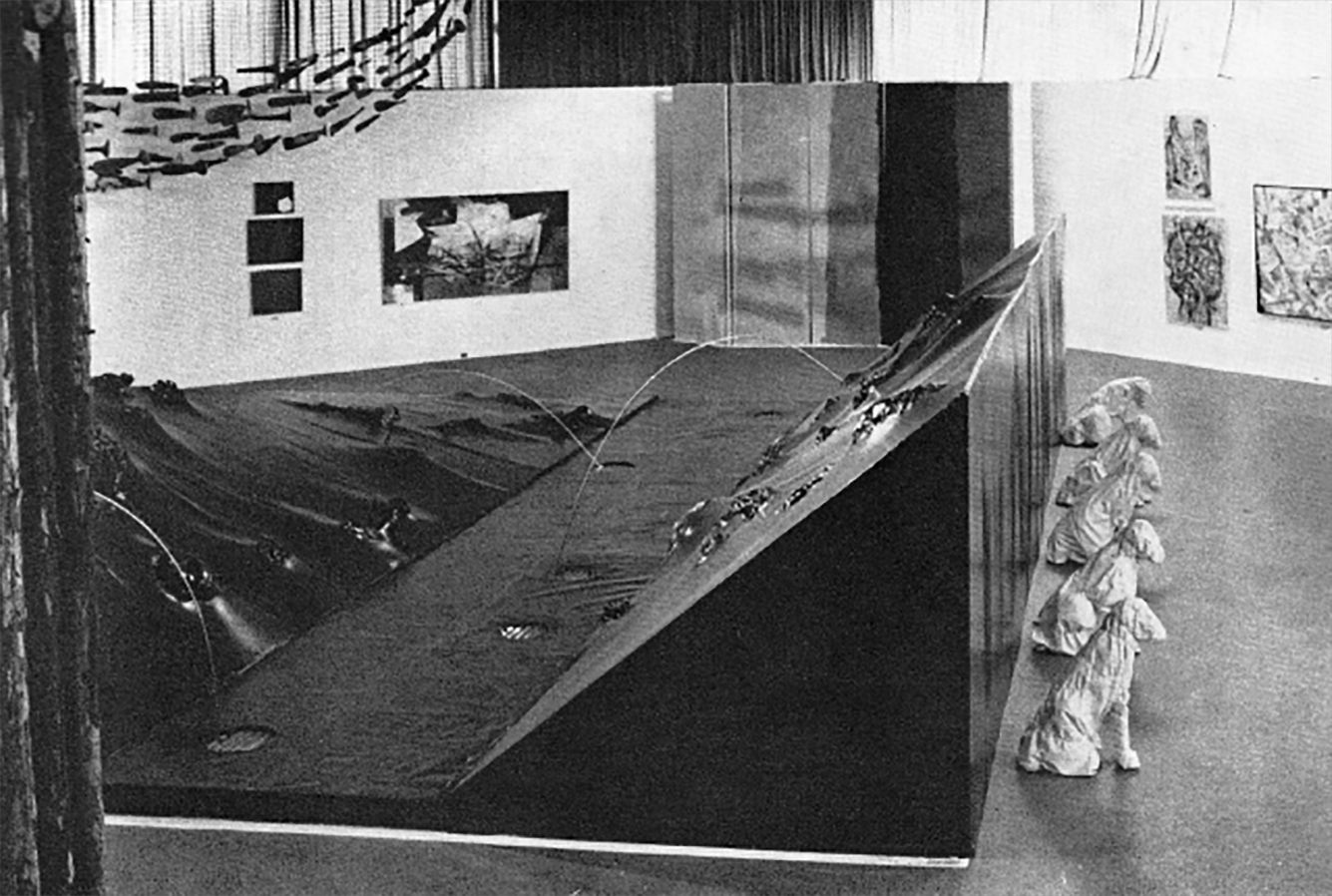

According to the artists’ written concept, which was submitted to the jury in lieu of the work itself, Fluß-Uferzone was intended as an “expansion and enrichment of the collective space” that would offer new “points of view” by making “visible the changing relationship between the river, its banks, and people.”31 They called the river “a metaphor for flow, for movement.”32 Photos of the work in situ show how it fulfilled the artists’ intention for it to be a “nexus point or link” (Bindeglied) within the exhibition, connecting to Sándor Dóró’s mobile of fish, which swam overhead, and Bridge and Ark (Brücke und Arche) by Jörg Sonntag and Andreas Hegewald, a large wooden bridge that stood perpendicular to Fluß-Uferzone.33

Hampel and Fischer had been inspired by a stretch of the Elbe river between Heidenau and Pirna. This area contained a number of factories, including one for making paper. These factories dumped wastewater from their operations directly into the river, contributing significantly to the polluted state of the Elbe. Pollution was a major concern for many in East Germany. In fact, it had gotten so bad by the early 1980s that the State had stopped reporting environmental numbers in 1982.34 This had not always been the case. As historian Dieter Rink has noted, East Germany was actually “one of the first countries in the world to take political action in response to environmental pollution and destruction.”35 Believing that “nature, like workers, must be preserved from the exploitation of capitalism,” the SED had embedded environmental protections into the 1968 constitution.36 It then set up a Ministry of Environmental Protection and Water Management in 1972—one of the first in the world—to implement environmental laws (Landeskulturgesetz), such as installing filters to reduce emissions and imposing fines for not following regulations.37

But competition between the two Germanys led to a shift away from environmental concerns in the 1970s as East Germany—under Erich Honecker—turned to a greater emphasis on consumer goods to counteract the allure of the West amongst its citizens. This shift in priorities led, in turn, to a ramping up of production and a relaxing of environmental protections when they conflicted with that goal. As scholar Julia Ault has noted, the economy came before ecology.38 As a result, East Germany became one of the most polluted countries in Europe by the 1980s and suffered from a long list of environmental problems, including air and water pollution, forest die-off, soil erosion, and exhaustion, as well as large-scale destruction of the countryside by coal mining.39

Although interest in environmental issues waned at the State level after Honecker took office, it continued to grow amongst the populace, often under the aegis of the Protestant Church, which was the largest church in East Germany, and one that, beginning in 1978, had relative autonomy from the State.40 Beginning in the 1970s, church leaders organized lectures and exhibitions about the environment, the proper stewardship of which was seen as a Christian value. In 1980, they founded East Germany’s first ecologically oriented newsletter, Briefe – Zur Orientierung im Konflikt Mensch-Erde [Letters on the Orientation of the Man-Nature Conflict], which was published semi-annually.

This newly emerging environmental movement was especially strong in Saxony, where people engaged with problems caused by brown coal, the chemical industry, the Soviet uranium plant at Wismut, and dying forests.41 In 1983, for example, an “Ecological Working Group” in Dresden decided that they needed to take action against “the resignation they saw in the world around them and to assume ‘responsibility for the earth… and the future of God’s creation.’ They presented the idea of the Green Cross, like an environmental red cross.”42 One concrete result was the development of a “Clean Air Vacation for Kids” program to provide children and their families with a ten-day vacation in less-polluted regions.43

In 1987, a year before the Blue Wonder exhibition opened, the issue of pollution, and especially water pollution, was the focus of much attention in Dresden. Greenpeace, for example, ran a poster campaign about how polluted the Elbe River was.44 They also lent water testing equipment to an environmental group in Dresden that, as Merrill E. Jones explains it, stood “in the town square with a basin of filthy water from the Elbe and a sign saying, ‘This is your drinking water.’”45 Additionally, another exhibition included an analysis of the water from the Elbe River to try to inform people about just how polluted it was, although the authorities ultimately shut it down.46

It is in this context that Hampel and Fischer decided to take a walk together along the Elbe, taking many photographs along the way.47 In one, a factory appears with a mountain of trash next to it. In another, Fischer stands atop a massive pipe emptying wastewater into the river. As they both recalled later, there was no way for them to determine the toxicity of the wastewater they were seeing, and no one they could ask about it or to whom they could complain.48 Hampel stated that she cried when she saw all the contamination, as Fischer confirms: “Angela stood on the pipe and howled. She was finished. She was really affected.”49 It was this hidden-in-plain-sight degradation that the artists wanted to capture in their work. As Fischer explained it, “the visual has more impact on the viewer. When you just have numbers, it’s too abstract. We wanted it to be seen. We translated it into art.”50

The work they created in response (Fig. 2), roughly 6 meters long, was an artistic recreation of a stretch of the Elbe River in miniature, abstracted as a flat walkway with angled banks on each side.51 They covered the structure in taut black plastic that suggested a layer of black oil. On the floor of the “river” were five foot-wide holes covered by grates; inside each were small lights illuminating a pool of water. The ends of golden fishing poles disappeared into three of them, making three thin arches from the “shore.” As Fischer explained, “the fishing poles were a joke. You couldn’t eat fish from the Elbe back then.”52 The banks that rose up on both sides had large, sharp protrusions at random intervals and were made with plastic waste that the artists had collected. This material had washed out of the factory’s paper-making machines in strange forms they found suggestive of sculpture.53 As Fischer stated, “We collected them as an expression of artificiality. A distillation of these refineries. It was like a feeling of graves. They seem so sick. Deformed. Like failed genetics.”54 These protrusions also suggested animals covered in oil and struggling to survive.

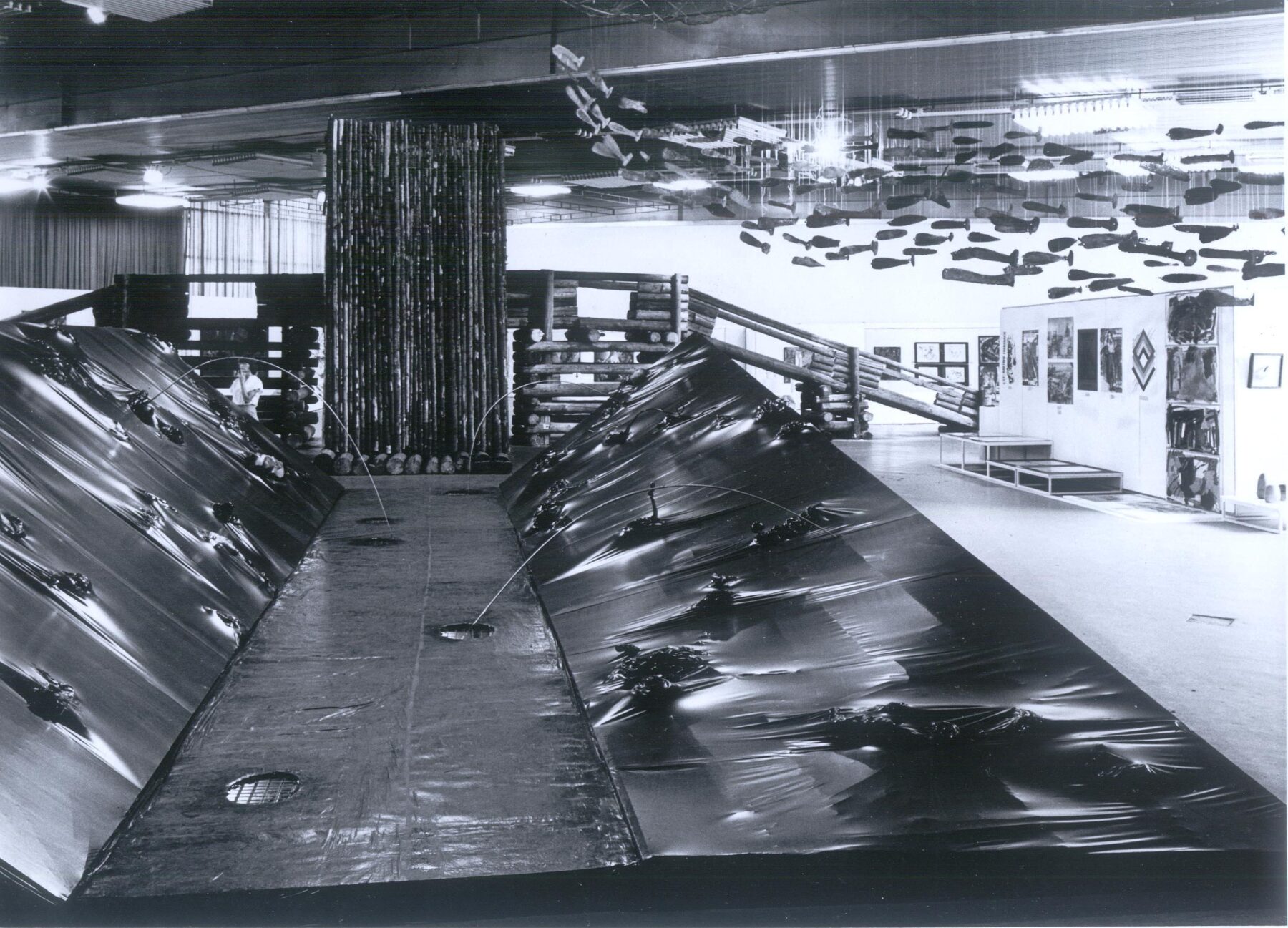

Accompanying the installation was a flyer (Fig. 3) printed on thick orange card stock and folded in three.55 A photograph of a polluted scene from the Elbe was printed in black on both sides as a backdrop to four texts. On the outside, the artists offered a sober account of the state of the Elbe River:

[U]ntreated wastewater flows into the Elbe every day. The main causes of this condition in the Upper Elbe area are the artificial silk plant in Pirnau, the fluorine plant in Dohna, and the pulp paper plant in Heidenau, among others.56

They then listed a series of seven toxins with question marks next to them.57 How much of each was in the Elbe, they wondered. Their text then pointed out the “enormous burden of non-biodegradable substances from households (surfactants in fabric softeners, phosphates…)” before turning to the amount of drinking water used in Dresden each day, “1/3 of it for toilet flushing,” and how the need for fresh water would only rise in coming years.58

In contrast to this factual text on the outside of the flyer, there were three literary texts on the inside. The longest of the three was an excerpt from Forest Fountain (1866) by the popular nineteenth-century Austrian writer Adalbert Stifter. In the excerpt, a grandfather describes the beauty of the Bavarian Forest to his grandchildren. Water plays an important role in his description, with the grandfather ultimately pointing out that “water gives all beings, even the grasses, happiness and health… if you have lost both happiness and health, you will get it again if you drink from this water and breathe from this air.”59 This text also appeared, handwritten, on one of the short sides of the installation, the importance of clean water thus standing in stark contrast to the pollution evident in Fluß-Uferzone.

In the flyer, Stifter’s words were flanked by shorter texts by the artists. In Hampel’s, on the left-hand side of the flyer, she describes a man bending over a natural fountain to take a drink of water, but rather than seeing his own reflection there, he sees a woman “with hair like threads of seaweed and pearls in it” staring back at him.60 It is Undine, a water nymph who falls in love with a human man only to be betrayed by him later.61 Hampel thus juxtaposes man and nature in gendered terms and suggests that man will betray the latter. In Fischer’s text, on the right, he describes children playing with their pails and buckets in the mud. Their father comes home from a day of work, excited about the new building projects with which he is involved: these projects will help protect them from floods by sealing the water “in veins made of concrete and steel.”62 It is a story in which Fischer subtly criticizes humanity’s desire to control nature.

This story perhaps also connects to another part of the installation and the issue of control: five dogs (Fig. 4) wrapped in a white plastic cloth tied together with rope, sitting at attention behind one of the riverbanks, which ends with a steep vertical drop. These dogs refer to the East German secret police, or Stasi, the Dresden headquarters of which ran along the Elbe near what is today the Waldschlösschen Bridge. The Stasi employed security dogs to patrol the area between the buildings and the river. In Fischer’s words, “they were on the terraces, each with a 150-foot steel line. Each had its own running area… and when people came by, you heard such a commotion… That’s how we knew they were there.”63 That the dogs were a symbol of the Stasi was a reference that, according to Fischer, anyone from Dresden, indeed the GDR, would have recognized at the time.

But it was pollution that was the main focus of Fluß-Uferzone. This theme was also at the center of a performance that Hampel and Fischer presented at the opening of the Blue Wonder exhibition on July 22, 1988. Wrapped in black plastic bags (Fig. 5), the same material used to cover the sloping banks of the work, the two artists “slithered” from one end of the installation to the other (Fig. 6). According to Hampel, “we were covered in plastic film and nearly suffocated. We were like worms. The kids cried. They were scared. They cried.”64 Fischer stated that the performance took a long time: they crawled like worms and had no orientation.

Reception

Given the tendency in current scholarship to assume experimental art was taboo, one might expect that Fluß-Uferzone and its accompanying performance, both of which were openly critical of the environmental situation in East Germany, would be ignored or criticized by the press—the opposite was, in fact, the case. The Sächsische Zeitung (SZ), which was one of Dresden’s most important daily newspapers and an official organ of the SED, ran a series of at least eight articles about the exhibition that summer, all of which mentioned the installations, with many singling out Fluß-Uferzone for praise. Several also included a black-and-white photo of the work.65 In an article published the day after the opening, for example, an unnamed SZ author pointed out the “variety of artistic forms” in the exhibition, noting that it included more than 350 works of “painting, graphics, sculpture, photography, commercial art, design, and craftwork” as well as installation art (raumgreifende Objekte).66 The article specifically mentions Sonntag’s wooden bridge (“set up with the help of Soviet garrison troops”) and Fluß-Uferzone, including the performance at the opening.

In another longer article about the exhibition, the art historian Dr. Erhard Frommhold (1928–2007) begins by stating that entering Halle A on Fucikplatz is not as pleasant as it was four months earlier for the Tenth Art Exhibition of the GDR:

One no longer finds pretty paintings […]. Rather, one climbs through a river well-known to us: black, tar-like, viscous (quallig)—disgusting. Only now and again, illuminated from the depths, comforting clean tap-water puddles. It is the Acheron, that sluggish river into the dark underworld of Hades that one can first cross as a spirit, and only with the help of the evil, money-hungry ferryman Charon.

No! It is supposed to be the Elbe. And it is, too, somewhere near Heidenau or in Loschwitz at the Blue Wonder, say the artists Angela Hampel and Steffen Fischer. And indeed their work from wood, plastic (Folie), paint, tar, and alluvial pieces is a giant symbol… a warning in sculptural form that, as a black wonder, controls the meaning of the exhibition, but not to exhaust it. For these artists know of a possible rescue from the threatening calamity. They are indeed innocent young artists who have never been able to take a clean swim in the Elbe.67

Frommhold then discusses Hegewald and Sonntag’s installation, Bridge and Ark, before describing several more traditional works in the exhibition, pointing out that:

one no longer goes from one painting to another painting, from one sculpture to another sculpture, responding with delight or anger. Rather, the visitor is cornered by the designs (Gestaltungen) in the room […]. They are “dialogical art forms” […] works that speak to each other […] fitting into the whole or even defining the goal of the exhibition.68

He points out that this art is no longer about being “pretty” and thus is difficult for many viewers, but making such works is also difficult for artists. He then explains that “the disturbing world is more to blame than these young artists,” continuing by saying that “such disquiet is today a compass that should lead the way for every thoughtful person.”69

Another article focused solely on Fluß-Uferzone and was illustrated with a black-and-white photograph of visitors standing in the middle of the work. Written by Jens-Uwe Sommerschuh (born 1959), cultural editor of the Sächsische Zeitung, this article starts by pointing out how Hampel’s and Fischer’s paintings and graphics are already a well-known and important part of the Dresden art scene. Sommerschuh then notes that their “search for new formulations that transcend traditional genres” is also nothing new.70 He mentions A-ORT-A—an exhibition of installations the two had participated in the previous year at the Galerie Nord Dresden—as one of a number of other recent examples before quoting Hampel’s explanation of their interest in creating installations:

[T]his attempt to find other means of expression is not about experimentation… a painting is like a monologue; it remains “art on the wall.” In real space, the distance from the viewer is eliminated.71

He notes that people can walk through and touch Fluß-Uferzone: “One sees and senses how vulnerable the river and banks are.”72 He then describes the artists, in their performance, not as worms but rather as a reflection of the river itself, which “moved laboriously,” thus showing how “the river suffered… terrible agony.”73

The art historian Gabriele Muschter, who had given Hampel her first exhibition at the Galerie Mitte in Dresden four years earlier, published a negative review of the exhibition as a whole but offered high praise for Fluß-Uferzone. She began her text by saying that “in the exhibition, one experiences the ‘blue wonder’ more as a sense of disappointment. Disappointment over the lack of artistic potency, too few original ideas, and also a lack of engagement with the exhibition.”74 The exceptions, however, were Bridge and Ark and Fluß-Uferzone, “which in [their] direct ideas and their concrete execution stand up to international standards,” by which she presumably meant that they were as good as anything created in the West.75 She states that these two works, with their similarities, “form the core” of the exhibition, but are among “the few” that she found to be successful.76

Criticism of the exhibition but praise for Fluß-Uferzone was also shared publicly by at least one visitor to the exhibition. On August 6/7, the Sächsische Zeitung published two letters from readers. In the longer of the two, the author states he went to the exhibition with great expectations but was disappointed.77 In sharp contrast to the authors of the catalog, he found that the artists were too focused on themselves in their work:

I often stood in front of paintings or sculptures and didn’t know what the artist was trying to say […] an artwork should always have a message […] a message that the receiver can also understand. What good does it do me as a worker with a fully normal understanding of art, when, for example, critics and artists speak positively, and I’m at a loss […] I want to feel something in an artwork, to enter into the sensory world of the artist.78

Fluß-Uferzone was one of three works, however, that he singled out for praise: “the river landscape by Angela Hempel [sic] and Steffen Fischer also gave me a lot to think about. It showed quite precisely our environmental problems.”79

Although the majority of articles about the exhibition were published in the Sächsische Zeitung, the exhibition—and Fluß-Uferzone—reached beyond just local audiences. Neues Deutschland, the official party newspaper at the national level, for example, published a review the day before Blue Wonder opened. It described the exhibition as a focus on “truth and artistic quality,” one that demonstrated an “engaged courage to experiment,” and saw the installations as “a surprising moment in the exhibition,” mentioning both Bridge and Ark and Fluß-Uferzone by name.80 There was also the article by Lothar Lang in Weltbühne cited earlier. Lang called Fluß-Uferzone an “interesting work,” one that “warns us to not overuse water,” also describing it as “A warning of the end of times,” because it was covered in black.81 And in November 1988, a three-page article about the exhibition appeared in Bildende Kunst (Visual Arts), East Germany’s main art journal.82 A photograph of Fluß-Uferzone takes up nearly half of the first page, albeit inadvertently printed upside-down.83 The author makes a connection between this “working exhibition” and the controversial Herbstsalon exhibition that took place in Leipzig four years earlier. He also mentions Hampel and Fischer’s performance in passing. Toward the end of the article, the author points to other exhibitions in Dresden at the time that included installations: the Gruppe Meier in the Galerie Comenius and the Auto-perforation Artists’ From Ebb and Flow in the Leonhardi Museum.84

In a final review in the Sächsische Zeitung, published two days after the exhibition closed, Sommerschuh pointed out that more than 10,000 people had visited Blue Wonder in its three-week run, “a considerable number” considering the short length of time it was open and the fact that it was during summer vacation.85 He mentioned that the association-rich name of the exhibition—“blue wonder,” which refers not only to the Loschwitz Bridge but also to German Expressionism and to the state of being shocked or surprised—provoked curiosity and high expectations. “It is not the choice of artistic means that is decisive for its societal worth. More significant is how the artist, from the full choice of artistic possibilities […] strikes the nerve, the nuanced needs of the other!”86 He continued by saying that “it is of great importance that many artists raised existential questions […] questions about our social interactions with each other […] with our history […] with our environment […] and with our world as a philosophical category.”87 In the end, Sommerschuh stated, the exhibition succeeded in the task at hand, which was, in the words of artist Andreas Hegewald, “to make people think. That we recognize that we need to think.”88

The Blue Wonder exhibition closed in August 1988, but its works were not soon forgotten. A little over a year later, the Twelfth (and final) District Art Exhibition in Dresden opened in the midst of the demonstrations that would ultimately lead to the fall of the Berlin Wall a few weeks later. In its catalog, art historian Barbara Busch discussed the intermedial tendencies of art in Dresden, by which she meant performances and installation art. Pointing to a long tradition for such works in Dresden, she explains that the goal of such works is to “activate the public, to shake them up, to question moral concepts. It is about raising awareness.”89 She recalled Fluß-Uferzone, describing how the installation and performance “impressively and relentlessly drew attention to the pollution of rivers, the destruction of the environment, and thus of the earth,” and connected it to the Exxon Valdez oil spill that had occurred in Alaska a few months earlier.90 The worst oil spill in history at that point in time, it had covered 1,300 miles of shoreline in crude oil and killed thousands of birds and aquatic animals, a seeming live recreation of the inert skulls under black plastic in Fluß-Uferzone.91

Conclusion

The many reviews of the Blue Wonder exhibition in the summer of 1988, together with visitor numbers, reveal that it was an important exhibition that reached a large audience, one that extended well beyond Dresden. The press’ ongoing engagement was a reflection of a political and cultural desire in East Germany to make art accessible to the public.92 Through numerous texts in both local and national publications, art critics and art historians attempted to explain new works like Fluß-Uferzone to an audience more accustomed to looking at traditional media, especially paintings. In these texts, they expressed openness to engaging with the works on display, sometimes explaining their own coming to terms with them or including quotes from the artists about their intentions. The texts thus modeled how readers should respond to challenging artworks.

Angela Hampel and Steffen Fischer’s Fluß-Uferzone was—and is—a challenging work, not just for audiences at the time, but also for the many scholars today who tend to assume that experimental art in East Germany was created only by disaffected artists in marginal locations. Such a view implies a link between artistic style or medium and ideology, in this case, that experimental art and socialism are incompatible. But as Peter H. Feist himself stated in late September 1988, just a month after the Blue Wonder exhibition closed:

There is no clear, causal […] connection between social forces and artistic forms […] A style can correspond to or serve opposing social groups and their interests.93

Fluß-Uferzone is a clear example that experimental art in East Germany could be created by artists who did not reject socialist values and that such works could be exhibited in official Artists’ Union exhibitions and discussed openly in both the local and national press.

The problem that experimental art faced in East Germany was less a political problem, as it is so often presented today, than it was a generational one.94 Willi Sitte, president of the Artists’ Union from 1974–88, for example, strongly opposed its recognition by the Artists’ Union. Born in 1921, he was more than thirty years older than the majority of artists in the “Doors” exhibition. His generation had fought to make modern art acceptable in a context in which the East German government preferred nineteenth-century realism.95 This generation also held most of the positions of power in the East German art world during the Honecker era, a result of historical circumstances: World War II had decimated the older generations, leaving those born in the 1920s to fill the void. This created a glut of artists and cultural functionaries who were only beginning to reach retirement age in the late 1980s, thus inadvertently blocking younger generations, much to the latter’s frustration.

As the introduction of this article shows, Sitte did not support experimental art. He considered Happenings and Environments “stupidities” and refused to incorporate them under the aegis of the Artists’ Union.96 But he also stated that the Artists’ Union would “never forbid” such things, indeed was “against such things being forbidden.”97 Artists were free to experiment. They could, if they wanted to, “[go] into the forest and [strew] sand around” or “[retrieve] some kind of garbage from the dump…”98 For Sitte, the problem was less artists doing such things than the art critics who would “show up and designate all this as new and progressive, as avant-gardist.”99 Indeed, he worried that such “avant-garde escapades” would ultimately lead to the erasure of traditional conceptions of art, leaving East German artists in the future with “nothing more to say.”100

Significantly, it was in 1988—several months before Sitte stepped down as president of the Artists’ Union—when major changes began to happen in East Germany with regard to the official acceptance of experimental art forms.101 The Blue Wonder exhibition that summer marked the first time that a major exhibition at the district level included installation art, nearly a decade after such works first began to appear in East German galleries. Then in September 1988, Bildende Kunst, East Germany’s most important art journal, dedicated an entire issue to installation art, looking at historical precedents such as Lissitzky, Duchamp, and Schwitters, Western proponents such as Joseph Beuys and Edward Kienholz, and East German practitioners. By the summer of 1989, both installation art and performance art were regularly discussed and illustrated in Bildende Kunst, including works by East German artists, and both were also included in the district art exhibitions held in Dresden and Berlin. It is clear that had the Berlin Wall not fallen, experimental art—both installations and performances—would have been included in the XI. National Art Exhibition of the GDR in 1992/93 and would likely have been given its own section or sections in the Artists’ Union.102

Yet, rather than seeing the increasing acceptance of installation and performance art in East Germany as the result of a generational change cut short by the revolutionary events of 1989, many scholars today prefer narratives that emphasize experimental art in East Germany as “alternative,” “dissident,” or “marginal.” There is also a tendency to interpret these changes as the result of a decaying system that was losing its grip.103 This interpretation reads the artistic developments of the 1980s through the lens of 1989/90 and thus from a presentist perspective, one that knows 1988 was late in East Germany’s history. It is important to note, however, that few people at the time knew that East Germany was in decline, and none knew that the GDR was about to collapse. Indeed, even in the spring of 1989, just months before the Wall fell, people on both sides of the Wall were making pronouncements about its longevity.104

The presentist perspective evident in much art historical scholarship today ignores this fact as well as the realities and internal development of art in East Germany. It was first in 1977 that artists began experimenting with performance and installation art, itself a fairly late date in the GDR’s history when viewed from the present.105 By 1979, such works began appearing in art galleries where they were largely ignored—or dismissed—by the Artists’ Union; yet less than a decade later, they were featured in major Artists’ Union exhibitions, the result in large part of what German historian Anja Tack has noted was a generational shift taking place in the East German art world in those years.106

Viewed from a historically grounded perspective, the acceptance of installation and performance art in East Germany at the official level was in fact fairly rapid, the direct result of artists, art historians, and curators who actively promoted and defended such works, from Klaus Werner at the Galerie Arkade in 1979, where the first official performance work in East Germany took place, to Intermedia I in Coswig, near Dresden, in 1985, a two-day festival featuring punk music and experimental art organized by Micha Kapino, Christoph Tannert, and Wolfgang Zimmermann.107 Many of these actions predate Gorbachev’s calls for Glasnost and Perestroika and the revolutionary fervor that led to the fall of the Berlin Wall, although they shared their frustration with the conservativism of the East German gerontocracy.108 Nor were these artists, art historians, and curators dissidents wanting to undermine or overthrow the GDR. Indeed, as Werner himself stated in 1990, “Besides the courage to leave, there was also the courage to stay!”109 This courage to stay, however, sometimes meant having to pay for one’s convictions: Werner lost his job as director of the Galerie Arkade in 1981, for example, after crossing too many lines in his support of experimental art.110

Fluß-Uferzone challenges current understandings of East German art on many levels, including the fact that it was highly critical of the environmental pollution evident in East Germany and even made a nod to the Stasi. Although the latter was largely ignored in the press, the former was a feature of much of the (positive) discussion that ensued. Hampel and Fischer were not the first to engage critically with pollution in their art. Wolfgang Mattheuer, for example, hints at it in a number of his paintings, such as Friendly Visit to the Brown Coal District (Freundlicher Besuch im Braunkohlenrevier, 1974). But Fluß-Uferzone is one of the first to do so without ambiguity.111 Nor did the artists experience any political repercussions as a result.

Fluß-Uferzone’s criticisms of environmental pollution were intended to bring attention to the issue in the hopes of making a change. Its criticisms, however, are just as valid today as they were in 1988, if not more so in the face of accelerating neoliberal exploitation and climate change. The Exxon Valdez spill of 1989, for example, pales in comparison to the Deepwater Horizon spill of 2010.112 In this context, Fluß-Uferzone would fit well alongside contemporary works like Ai Wei Wei’s Oil Spills (2006) and Cai Guo-Qiang’s Silent Ink (2014). The questions it raises about water and our (mis)use of it also touch upon increasing fears and realities of water scarcity as a major problem of the twenty-first century.

This article has focused on Angela Hampel and Steffen Fischer’s Fluß-Uferzone to argue against western bias and presentist understandings of experimental art in East Germany. Fluß-Uferzone was one of four installations and three performances by these artists in the latter half of the 1980s, all in official venues. Neither was a dissident artist, although Hampel did face challenges from cultural functionaries on occasion; such challenges were not uncommon for artists who pushed against—and ultimately moved—accepted boundaries. Indeed, both Hampel and Fischer saw East Germany as the better Germany, even if in need of significant reform: an antifascist, anti-imperialist, anti-capitalist Germany committed to gender and economic equality as well as to the arts, which it supported both financially and through its cultural policies. This article thus also pushes against the tendency in current scholarship to link artistic style—or in this case, media—to a particular political perspective. To equate performance and installation art in East Germany with dissidence or an embrace of the West is to misunderstand many of the artists who created such works. Indeed, as Briana Smith stated, “for many, the flawed state socialism of the GDR was preferred to the capitalist market system of the West. As the VBK increased its temporary visas allowing artists and art historians to travel to the West, some returned with a hardened resolve to remain in the GDR and make it better.”113 Installations like Fluß-Uferzone were created by East Germans for East Germans to “actively account for the problems and needs of the present,” something that Feist stated in his speech twenty-four years earlier. And as he states for art history, so too their work “not only reflects a given social situation; as a creative act, it also works upon society to change it.”114

- [1] Peter H. Feist, Principles and Methods of A Marxist Kunstwissenschaft—Attempt at an Outline, trans. Tamara Golan and Felix Jäger, in Tamara Golan and Felix Jäger, eds., Selva 5 (spring 2024), 39. Originally published in 1966, this text was based on a speech he gave in Munich in November 1964; for more on the relationship between this text and his speech, see: Tamara Golan and Felix Jäger, “‘Our Beautiful, Difficult, Subject:’ Peter Feist’s Marxist Method,” in this issue. I have made connections to Feist here and elsewhere in the text because this article is part of a special issue devoted to Feist.

- [2] For more on these freezes and thaws as well as the battle over artistic style during the Ulbricht era, see: April A. Eisman, Bernhard Heisig and the Fight for Modern Art in East Germany (Rochester, NY: Camden House, 2018).

- [3] Erich Honecker, in a speech given at the Fourth Congress of the SED’s Central Committee. The speech was published in Neues Deutschland, the Party newspaper, on December 18, 1971.

- [4] This final thaw had already begun to set in by the late 1960s. The “constructivist” artist Hermann Glöckner, for example, had small solo exhibitions in 1968 and 1969 in Berlin and Dresden, respectively. Honecker’s speech in December 1971 made this shift official. Shortly thereafter, the formerly controversial expressionist painters Willi Sitte (1921–2013) and Bernhard Heisig (1925–2011) became president and vice president, respectively, of the Artists’ Union, and by 1977, even Glöckner’s fully abstract works were included regularly in the painting and graphics section of the national art exhibitions of the GDR. The greater freedom was not limited to stylistic choices; in the 1970s, artists also began to create “complex paintings” (Komplexbilder) that addressed not only the complexities of history but also the challenges of everyday life, such as the exhaustion caused by manual labor and the alienation of modern life.

- [5] The Leonhardi Museum, founded in 1963 by a group of young artists in Dresden, was an official gallery of the Artists’ Union at the time of the “Doors” exhibition. For a complete accounting of this museum and its exhibition history, see: Angelika Weißbach, Frühstück im Freien – Freiräume im offiziellen Kunstbetrieb der DDR. Die Ausstellungen und Aktionen im Leonhardi-Museum in Dresden 1963-1990 (Berlin: Humboldt-Universität, 2009).

- [6] Weißbach, Frühstück im Freien, 174. Although the actual numbers—70 to 200 per day—pale in comparison to attendance figures for exhibitions in major venues like the Albertinum, they were considerable for the Leonhardi Museum, which was a small gallery space located on the outskirts of Dresden.

- [7] Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Fonds Willi Sitte, Protokoll des Redebeitrages von Willi Sitte auf der Sitzung des Zentralvorstandes des VBK am 13.3.1980, as found in Paul Kaiser, “Suggestion und Recherche. Eine quellenkritische Fallstudie zur Aktenlage um Willi Sitte,” in Georg Ulrich Grossmann, ed., Politik und Kunst in der DDR. Der Fonds Willi Sitte im Germanischen Nationalmuseum (Nuremberg: Germanisches Nationalmuseum, 2003), 96–107, here 106.

- [8] The Artists’ Union had separate sections for each of the main areas of artistic production, including painting/graphics, sculpture, photography, commercial art, and design. The number of sections grew over time.

- [9] Sarah James, Paper Revolutions: An Invisible Avant-Garde (Cambridge, MA & London: MIT Press, 2022), 15.

- [10] Paul Kaiser and Claudia Petzold’s exhibition and catalog, Boheme und Diktatur in der DDR: Gruppen, Konflikte, Quartiere 1970-1989 (Berlin: Fannei & Waltz, 1997) was one of the first to engage with East Germany’s experimental art scene. It came at a time when scholarship tended to emphasize East German painting. In recent years, the experimental art scene has eclipsed the “official” art scene amongst scholars, a fact that is particularly evident in the nascent scholarship in English, where four of the five books published since 2018 focus on experimental art.

- [11] This canon of experimental art stands as a counterpoint to the “official” canon that had previously dominated western understandings of East German art; the latter emphasized traditional media, especially painting, and was closely associated with artists like Bernhard Heisig, Wolfgang Mattheuer, Willi Sitte, and Werner Tübke.

- [12] Weißbach points out this elision with regard to the Leonhardi Museum in major exhibitions such as Boheme und Diktatur. Weißbach, Frühstück im Freien, 8.

- [13] Examples include: Susanne Altmann, Katarina Lozo, and Hilke Wagler, eds., Medea muckt auf. Radikale Künstlerinnen hinter dem Eisernen Vorhang (Cologne: Walther König, 2019); Paul Kaiser, Boheme in der DDR. Kunst und Gegenkultur im Staatssozialismus (Dresden: DIK, 2016); and Eugen Blume and Christoph Tannert, eds., Gegenstimmen. Kunst in der DDR, 1976-1989 (Berlin: Deutsche Gesellschaft e.V., 2016).

- [14] This hagiographic approach has also begun to emerge in the nascent literature on East German art in English; see: Sara Blaylock, Parallel Public: Experimental Art in Late East Germany (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2022). For more on the reception of East German art in unified Germany, see: April A. Eisman, “Whose East German Art is This? The Politics of Reception After 1989,” in Imaginations, Journal of Cross-Cultural Image Studies, vol. 8, no. 1 (2017), 79–99. For more on its reception in English, see: Eisman, Bernhard Heisig, 4–11.

- [15] Christoph Tannert, Eugen Blume, and Klaus Werner have all played an important role since German unification in drawing attention to the more experimental artists they championed in the GDR.

- [16] Briana Smith makes a similar statement in the introduction to her book Free Berlin: Art, Urban Politics, and Everyday Life (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2022), 11: “Many studies [of experimental art in East Germany] focus on underground art appearing in illegal private spaces to the exclusion of the experimental art that appeared in the light of day [… This] preoccupation with the underground has perpetuated the sense that artistic experimentation and the divergence from traditional art forms could exist only in such spaces. This was simply not the case.”

- [17] It is important to point out here that no one knew or even suspected that the Berlin Wall would be breached the following year or that the Soviet Union would cease to exist just a few years later. In 1988, the eastern bloc’s future seemed secure; it was also less than a decade after installation and performance art first emerged onto the East German art scene. I will return to these ideas in the conclusion.

- [18] The Blue Wonder exhibition does not appear, for example, in Frank Eckhardt and Paul Kaiser, eds., Ohne uns!: Kunst und alternative Kultur in Dresden vor und nach ‘89 (Dresden: Efau, 2009), or in Paul Kaiser’s massive, 471-page book on the alternative scene in East Germany, Boheme in der DDR. Christoph Tannert and Bernd Lindner, on the other hand, mention it, but only in passing: Christoph Tannert, “Pflöcke im Niemandsland. Rückblicke auf eine Kunst der Selbstbehauptung in der DDR,” in Paul Kaiser, Christoph Tannert, and Alfred Weidinger, eds., Point of No Return. Wende und Umbruch in der ostdeutschen Kunst (Leipzig: MdBK, 2019) 38–64, here 48; Bernd Lindner, Nähe + Distanz. Bildende Kunst in der DDR (Erfurt: Landeszentrale für politische Bildung Thüringen, 2017), 152.

- [19] Hampel was singled out for praise in reviews of the Dresden heute exhibition, which traveled to five locations in West Germany and Switzerland in 1985–86. This exhibition was organized by Hedwig Doebele, a West German gallerist who regularly exhibited Dresden artists in the West. Dresden heute was the first time she exhibited Hampel.

- [20] This belief that East Germany was the better Germany was not uncommon among artists and writers in East Germany, although that is not to say that they agreed with how their country was run. Hampel and Fischer, for example, were trying to change the system from within through their art and active participation in the Artists’ Union.

- [21] Angela Hampel, interview with the author, June 11, 2013. She did so with her art, but also through her engagement with the Artists’ Union, where she served on committees and gave speeches. Her most famous speech was in 1988, when, at a national meeting of the Artists’ Union, she brazenly criticized the lack of gender equality in the Artists’ Union’s committees, juries, commissions, exhibitions, collections, and media coverage. These attempts meant that sometimes the State lumped her together “with people who really wanted to abolish the State.”

- [22] Steffen Fischer, interview with the author, April 21, 2017. Fischer called this a “third way.” The belief in a third way was not unique to Fischer and is, in fact, well documented in Anglo-American scholarship on East German literature. As Stephen Brockmann has written with regard to the demonstrations that led to the fall of the Berlin Wall, for example, “many writers and intellectuals saw the revolution in the GDR as above all a socialist revolution aimed at actually realizing the promises of socialism that had been ignored for the last forty years.” Stephen Brockmann, Literature and German Reunification (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1999), 48. Emphasis in the original.

- [23] The National Art Exhibition (Kunstausstellung der DDR) took place every four to five years in Dresden between 1946 and 1988. This exhibition focused on recent artworks by East German artists. Its catalogs, of which there are ten, offer a great overview of major trends in East German art across forty years.

- [24] The works were chosen by the “Working Group of Young Artists” from the local branch of the Artists’ Union.

- [25] The cover was designed by Jörg Sonntag and Via Lewandowsky. Identification with place was common in East Germany, where regional styles—and rivalries—developed as a result of the division of the country into fourteen districts. The Artists’ Union, for example, had a local branch in each district, and each branch had a major exhibition every few years to showcase the work being created there.

- [26] “Junge Künstler bereiten in Dresden neue Ausstellung vor,” Neues Deutschland, July 12, 1988. At least one work was included by every artist who answered the call.

- [27] Lothar Lang, “Dresden: Blaues Wunder,” Weltbühne, August 2, 1988, 983–85, here 983. A number of different terms were used for installation art in East Germany, including Object Art, Installations, and Environments.

- [28] Lang, “Dresden: Blaues Wunder,” 983–85. It is also important to note that Lang himself refers to the Herbstsalon exhibition in his text, a fact that challenges the assumption commonly found in current scholarship that this exhibition was too controversial for public mention.

- [29] “Fluß-Uferzone” does not lend itself to easy translation. River-Littoral Zone or River-Shore Zone are the most exact, although both are awkward in English. River-Bank might be the most elegant translation, but it loses some of the meaning. For this reason, I have left the title in German.

- [30] One of the murals was for a Trafohaus (a transformer station) of which there appear to be no surviving photographs. The other was for a youth club and became the center of controversy the year it was completed. For more on this controversy, see: April A. Eisman, “Art and Controversy in Dresden: Angela Hampel and Steffen Fischer’s Mural for the Jugendklub Eule (1987),” in April A. Eisman and Gisela Schirmer, eds., Kunst in der DDR – 30 Jahre danach, Kunst und Politik: Jahrbuch der Guernica-Gesellschaft (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2021), 85–97. The group exhibition at the Galerie Nord, titled A-Ort-A, included installations by Steffen Fischer, Matthias Jackisch, Angela Hampel, and Maja Nagel. It ran from December 6, 1987 until January 23, 1988. There were also two performances that accompanied the exhibition. A-Ort-A is another example of experimental art being shown in an official venue, although much smaller than that of the Blue Wonder.

- [31] Steffen Fischer and Angela Hampel, “Konzeption der Flussbett-bzw. Uferzone,” Akademie der Künste Archiv: VBDK-Dresden 64.

- [32] Fischer and Hampel, “Konzeption der Flussbett-bzw. Uferzone.”

- [33] Bridge and Ark was built with the help of Soviet soldiers stationed in Dresden, a fact frequently commented upon in reviews of the exhibition.

- [34] Merrill E. Jones, “Origins of the East German Environmental Movement,” German Studies Review, vol. 16, no. 2 (May 1993), 235–64, here 243; Julia E. Ault, “Defending God’s Creation? The Environment in State, Church, and Society in the GDR, 1975–1989,” German History, vol. 37, no. 2 (2018), 205–26, here 212.

- [35] Dieter Rink, “Environmental Policy and the Environmental Movement in East Germany,” Capitalism Nature Socialism, vol. 13, no. 3 (September 2002), 73–91, here 73.

- [36] Ault, “Defending God’s Creation?” 206.

- [37] Ibid., 206, 210.

- [38] Julia E. Ault, Saving Nature under Socialism: Transnational Environmentalism in East Germany, 1968–1990 (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2021), 74.

- [39] Rink, “Environmental Policy and the Environmental Movement in East Germany,” 74.

- [40] On March 6, 1978, the SED granted the Protestant Church in East Germany autonomy to make its own decisions about church activities, organization, and staffing as well as in the running of three theological institutions. According to Merrill Jones, this was not so much a sudden change as it was formal recognition of what had been developing over the 1970s. Jones, “Origins of the East German Environmental Movement,” 239.

- [41] Brown coal, or lignite, was a major source of energy in East Germany. Cheap to mine, it is one of the dirtiest forms of fuel to burn, contributing significantly to air pollution as well as acid rain and forest die-off. Julie E. Ault, “Protesting Pollution: Environmental Activism in East Germany and Poland, 1980–1990,” in Astrid Mignon Kirchhof and John R. McNeill, eds., Nature and the Iron Curtain (Pittsburgh: Pittsburgh University Press, 2019), 151–68, here 153–54.

- [42] Ault, “Defending God’s Creation?” 217–18.

- [43] Jones, “Origins of the East German Environmental Movement,” 245.

- [44] Rink, “Environmental Policy and the Environmental Movement in East Germany,” 84.

- [45] Jones, “Origins of the East German Environmental Movement,” 250.

- [46] Rink, “Environmental Policy and the Environmental Movement in East Germany,” 84.

- [47] These photographs were not part of the final artwork.

- [48] Steffen Fischer, interview with the author, July 7, 2017.

- [49] Angela Hampel, interview with the author, June 12, 2017; Fischer interview.

- [50] Fischer interview.

- [51] The size of the work was mentioned by Barbara Barsch in her article “Die Bretter, die die Welt bedeuten. Zu intermedialen Tendenzen in der Dresdner Kunst,” in 12. Kunstausstellung des Bezirkes Dresden (Dresden: Rat des Bezirkes Dresden, 1989), 15–17, here 17.

- [52] Fischer interview. In some of the photos, a school of small metal and textile fish hang down from the ceiling. These were part of an installation by the Hungarian-born artist Sándor Dóró (born 1950) entitled Fische (Fish), 1988. Although not intended as part of Fluß-Uferzone. Dóró, Hampel, and Fischer nonetheless discussed the hanging of it so the works would correspond with each other.

- [53] According to Hampel, they also used animal skulls they had procured from a slaughterhouse and cleaned up before pouring tar on them, like the pollution in the water, which they then positioned to emerge from the black plastic sides as if they were swimming. Hampel interview, 5.

- [54] Fischer interview.

- [55] In response to my questions, coming more than thirty years after the exhibition took place, Fischer stated that he thinks they printed between fifty and one hundred flyers and made them available in a box attached to the back of the installation. Steffen Fischer, email to the author, November 17, 2022.

- [56] Fluß-Uferzone flyer.

- [57] The toxins they listed in the flyer included heavy metals, chlorinated hydrocarbons, chlorides, sulfides, phosphates, nitrates, and cyanides.

- [58] Fluß-Uferzone flyer.

- [59] Ibid.

- [60] Angela Hampel’s text in the Fluß-Uferzone flyer.

- [61] Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué and E. T. A. Hoffmann, among others, wrote works based on the legend of Undine, but it was Ingeborg Bachman’s 1961 version of the story that had the most direct influence on Hampel. She would go on to create a number of works on this theme, including two permanent sculptures of Undine along the Elbe River.

- [62] Steffen Fischer’s text in the Fluß-Uferzone flyer.

- [63] Fischer interview.

- [64] Hampel interview.

- [65] These photos were taken from a variety of angles.

- [66] “Junge Künstler präsentieren ‘Blaues Wunder,’” Sächsische Zeitung, July 23/24, 1988.

- [67] Erhard Frommhold, “Kunst im Fluß – Unruhe aus unbändiger Überlebenslust,” Sächsische Zeitung, August 3, 1988, 4.

- [68] Frommhold, “Kunst im Fluß,” 4.

- [69] Ibid.

- [70] Jens-Uwe Sommerschuh, “Verletzt und berührt. Fluß-Ufer-Zone von Angela Hampel und Steffen Fischer,” Sächsische Zeitung, August 2, 1988, 4.

- [71] Sommerschuh, “Verletzt und berührt,” 4.

- [72] Ibid.

- [73] Ibid.

- [74] Gabriele Muschter, “Schärfer über den Umgang mit dem Leben nachdenken,” Sächsische Zeitung, August 11, 1988, 4.

- [75] Muschter, “Schärfer über den Umgang,” 4. East Germans were well informed about art in the West, even if they were often unable to travel there to see it.

- [76] Ibid.

- [77] “Leser zur Ausstellung ‘Blaues Wunder.’ Mit dem Künstler will ich mitfühlen können,” Sächsische Zeitung, August 6/7, 1988, 4.

- [78] “Leser zur Ausstellung ‘Blaues Wunder,’” 4.

- [79] Ibid.

- [80] “Junge Künstler bereiten in Dresden neue Ausstellung vor,” Neues Deutschland, July 21, 1988. This article also appeared in the Sächsische Zeitung on the same day with the title, “Um Wahrhaftigkeit und künstlerische Qualität.”

- [81] Lang, “Dresden: Blaues Wunder,” 984. Lang actually misidentified the work, thinking it was Quelle by Lothar Rericha and Gudrun Trendafilov. Sommerschuh pointed out this error in his August 9 article in the Sächsische Zeitung.

- [82] Gunter Ziller, “Dresden: Blaues Wunder,” Bildende Kunst 11 (1988), 518–20.

- [83] The photo can be difficult to parse for those unfamiliar with the work or exhibition.

- [84] The author does not use the term Auto-perforation Artists, but rather lists out the four artists by name. The Gruppe Meier, a group of three sculptors who created installations and performances in Dresden in the 1980s, is another example of important artists at the time who have been largely ignored in current scholarship.

- [85] Jens-Uwe Sommerschuh, “Vielfalt, Offenheit und Problembewußtsein,” Sächsische Zeitung, August 16, 1988, 4.

- [86] Sommerschuh, “Vielfalt, Offenheit und Problembewußtsein,” 4.

- [87] Ibid. I have removed the names of the artists from the English translation in the text for ease of reading. They are Leonore Adler, Ulrich Schollmeyer, Wolfgang Smy, Reinhard Springer; Frank Dierchen, Hubertus Giebe; Angela Hampel, Steffen Fischer; and Andreas Hegewald, Jörg Sonntag, respectively.

- [88] Ibid. Hegewald stated this in conversation with an SED member during a tour of the exhibition.

- [89] Busch, “Die Bretter, die die Welt bedeuten,” 16.

- [90] Ibid.

- [91] The Exxon Valdez spilled 10.8 million gallons into the Prince William Sound after hitting a reef on March 24, 1989.

- [92] Feist stated that art should be “accessible and tangible to as many people as possible.” Feist, Principles and Methods, 52. Emphasis in original.

- [93] Peter H. Feist, “Neue Überlegungen zum Forschungsgegenstand ‘Kunstverhältnisse,’” in Ulrike Krenzlin et al., Kunstverhältnisse. Ein Paradigma kunstwissenschaftlicher Forschung (Berlin: Akademie der Künste, 1988), 14.

- [94] For more on the battles fought by a younger generation at this time, see: Anja Tack, Riss im Bild: Kunst und Künstler aus der DDR und die deutsche Vereinigung (Göttingen: Wallstein Verlag, 2021), 52–96.

- [95] For more on this older generation, see: Eisman, Bernhard Heisig.

- [96] Kaiser, “Suggestion und Recherche,” 106.

- [97] Ibid.

- [98] Kaiser, “Suggestion und Recherche,” 106.

- [99] Ibid.

- [100] Ibid.

- [101] Clauss Dietel was chosen as Sitte’s successor at the Artists’ Union at the X. Congress of the Artists’ Union, held November 22–24, 1988.

- [102] Already in January 1988, the Dresden artist Hubertus Giebe argued as much in an interview published in the Sächsische Zeitung: the “XI. [Art Exhibition of the GDR] must include environmental installations, performances, Happenings,” works that colleagues enjoy making but that “so far, have been relegated to small galleries.” Interview by Jens-Uwe Sommerschuh, “Das Kunstangebot ‘draußen’ ist größer und vielschichtiger,” Sächsische Zeitung, January 22, 1988.

- [103] For a recent example of this perspective, see: Blaylock, Parallel Public (2022).

- [104] For historically grounded perspectives on East Germany in its final years, see: Konrad Jarausch, The Rush to German Unity (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994) and Stephen Brockmann, The Freest Country in the World: East Germany’s Final Year in Culture and Memory (Rochester, NY: Camden House, 2023).

- [105] The beginning of performance and installation art in East Germany can be dated to 1977 or 1979, depending on the criteria used: 1979 marks the emergence of such works in art galleries; 1977, when artists began experimenting with these media, albeit not necessarily intending to create finished works of art. An early example of the latter was undertaken in a forest near Leussow in September 1977, sometimes misdated to 1975; remnants of this action survive as Leussow-Recycling (1979), a multiple made two years later.

- [106] For more on the battles fought by a younger generation at this time, see: Tack, Riss im Bild, 52–96. This is also a topic I engage with in my upcoming book, Defiant Images.

- [107] Gregor-Torsten Schade (Kozik) staged a performance at the opening of his 1979 exhibition at the Galerie Arkade, The Black Breakfast (Das schwarze Frühstück), which is widely considered the first performance by an East German artist. Frank Eckart, Eigenart und Eigensinn. Alternative Kulturszenen in der DDR (1980-1990) (Bremen: Edition Temmen, 1993), 24.

- [108] People started taking to the streets in the summer of 1989 in response to the faked election results of March 1989 and, unrelatedly, Hungary’s opening of their border shortly thereafter.

- [109] Klaus Werner in Werner Schmidt, ed., Ausgebürgert: Künstler aus der DDR, 1949-1989 (Berlin: Argon, 1990), 42–43, here 42.

- [110] The gallery was also permanently closed. Smith, Free Berlin, 41–42. Similarly, Zimmermann lost his job as head of the Clubhouse in Coswig and was shut out of the SED because of his involvement with the Intermedia festival in 1985. Weißbach, Frühstück im Freien, 215. Cultural policy toward experimental art relaxed considerably after 1985.

- [111] Mattheuer’s painting can be found online by searching for the artist’s name and German title of the work. It also appears as figure 18 in the open-access article located at http://imaginations.glendon.yorku.ca/?p=9487 (accessed 11/30/2022).

- [112] In comparison to the 10.8 million gallons spilled by the Exxon-Valdez, the Deep Horizon drilling rig spilled more than 200 million gallons into the Gulf of Mexico after an explosion in 2010.

- [113] Smith, Free Berlin, 108.

- [114] Feist, Principles and Methods, 39.