Socialist Realism in the Abstract: North Korea and the Problem of Cultural Reception Among Socialist Countries in the 1950s

When it first went to print in 1966, Peter H. Feist’s Principles and Methods of a Marxist Kunstwissenschaft landed in the wake of perhaps the most consequential shakedown of the protocols and parameters of socialist realism since the doctrine’s formal inauguration as the official cultural policy of the USSR in 1934. The sea change in question had come to a head with the marquee exhibition The Art of Socialist Countries (Iskusstvo sotsialisticheskikh stran), which opened at Moscow’s Central Exhibition Hall on December 26, 1958. Running through the spring of 1959, the exhibition brought together works by artists representing the constituent nations of socialist Eastern Europe, from East Germany to Romania, along with fraternal Asian countries, including China, North Korea, and North Vietnam. The exhibition’s significance in visually demonstrating the vast range of aesthetic approaches that had been adopted to date throughout the socialist world—often explicitly under the banner of socialist realism—was concisely summarized by Sergey Gerasimov, President of the Soviet Artists’ Union, when he exclaimed just prior to the opening: “The time has come to define the art of socialist realism on an international scale!”1

As Jérôme Bazin has argued, with The Art of Socialist Countries, Soviet leaders effectively heeded Gerasimov’s call and “gave up the idea of Moscow as the only place where artistic matters could be judged and decided.”2 The Moscow elite no longer considered it their prerogative to arbitrate over the precise contours of communist art throughout the Soviet bloc, much less across the global socialist sphere. Instead, as Bazin has written with Pascal Dubourg Glatigny and Piotr Piotrowski, a new phase of Soviet art was emerging in which Moscow would act as a “meeting place” rather than a control center.3

This relinquishing of control would allow artists greater means of access to—and leeway to experiment with—stylistic models that had previously remained foreclosed. In the Soviet context, this much had become obvious in 1956 with the opening of the Sixth World Festival of Youth and Students in Moscow, whereupon Soviet artists took in unprecedented showcases representing a spate of movements said to define modern art in the West.4 Two years later, The Art of Socialist Countries tested the ability of socialist realism to remain a meaningful designation while encompassing the divergent directions contemporary socialist artists worldwide had begun to explore, some of which involved techniques formerly deemed antithetical to socialist realism on aesthetic and ideological grounds.

Visitors to The Art of Socialist Countries certainly registered the disparity that obtained across the discrete national installations. While the representative artists of some countries rigorously adhered to the conventional means of figuration and modeling that had been affirmed as proper to socialist realism since the 1930s, those of other nations seemed to have abandoned any commitment to these core representational devices in favor of expressionist flourishes and abstraction. We know from Susan Reid’s examination of comments left in the exhibition’s visitor books that the Polish pavilion provoked especially passionate responses from Soviet audiences. Some supported Polish artists’ daring deviations from the accustomed aesthetics of socialist realism, while others denigrated what they saw as the self-indulgent escapades on display.5 Reid argues that by sparking contentious discursive engagement among visitors to the exhibition, the Polish pavilion paved the way for a revival of distinctly modernist modes of art production in the Soviet Union, a plethora of which would find traction in the age of the Khrushchev Thaw, coinciding with a renewed emphasis on individual social identities as integral to both art and civil society.

As convincing as Reid’s account remains, by isolating the most conspicuous espousal of modernist strategies in the exhibition, it risks giving the impression that The Art of Socialist Countries consummated a teleological unfolding of socialist realism wherein the stringent 1930s could not but give way to an opening of previously proscribed aesthetic options by the late 1950s. The implication is that such a shift became inevitable under the pressure of artists whose creative energies had for decades remained stifled. From this standpoint, the project of socialist realism comes to appear as a mandate with which artists simply made do, acting within the constraints placed upon them and persisting until the relative sanctioning of Western avant-garde art, and abstraction in particular, provided them with more compelling outlets for their pent-up formal and critical ambitions.6 While such a viewpoint is rarely articulated in explicit terms, one senses its leanings in the art historical treatment of nonconformist art of the socialist bloc, where the figure of the outsider artist is often made to represent the secret inner desires of those conscripted into the scheme of socialist realism. The well-rehearsed arc of Gerhard Richter’s career presents as an object lesson with respect to this tendency. Here we confront an example of an artist trained in the methods of socialist realism in East Germany, who, upon visiting documenta II in 1959 and having his eyes opened to the work of Jackson Pollock, Jean Fautrier, and others, threw off the shackles of affirmative state propaganda and defected to West Germany to pursue more formally rigorous and critically creditable tracks.7

In hoisting such a narrative as the de-facto dream of all socialist artists forced into the service of state-mandated aesthetic programs, there lingers the danger of recapitulating the logic that led the United States Information Services (USIS) to weaponize Abstract Expressionism throughout the Cold War. As is now well known, the agency aggressively promoted AbEx paintings as indexical evidence of the freedom afforded in the capitalist West, in ostensible contrast to the oppressive environments spawned and policed by communist adversaries.8 One way out of this problem is to revive the perspectives of those who remained faithful to the representational and ideological fundaments of socialist realism even as the method came under mounting stress in the post-Stalin era. This was indeed a position maintained and vocalized at a conference organized around The Art of Socialist Countries in March 1959, in which delegates from each participating nation gathered in Moscow to debate art’s relation to reality. While some Soviet artists boldly deprecated previously articulated codes of socialist realism as misaligned with reality, North Korea’s representative oil painter, Mun Hak-su, clung steadfastly to the idea of a global community of socialist artists united on both aesthetic and political grounds. For Mun, the very prospect of socialist internationalism was contingent upon a united vigilance in fending off the blight of artistic trends imported from the West, abstraction being the worst offender. In his mind, experimental diversions like those displayed in the Polish pavilion would only corrupt the clarity of vision for which artists should strive in giving optical form to a new communist world.

Mun’s stance signals a dilemma that hovered over the field of socialist realism in the 1950s: namely, the question of how each socialist nation was to receive the contemporaneous artistic output of brotherly countries, particularly as some socialist artists began openly to toy with techniques and stylistic modes derived from Western modernism. While art was touted as a means by which socialist countries could learn from and about one another, hard distinctions had to be drawn between examples that were worthy of acclaim and those that should be written off as aesthetically and politically misguided.

To explore how this dilemma played out in the North Korean context, in what follows, I situate Mun’s war on abstraction at the Moscow symposium in relation to the reception of exhibitions of art from socialist Eastern Europe that were held in Pyongyang throughout the late 1950s. As part of the larger project of this special issue, Feist’s text will serve as a recurring touchstone throughout. I find that one significant use value of Feist’s essay lies in how it flags a trail of pressure points that inflected the terrain of socialist realist art production and discourse throughout the international socialist camp at the time. I have in mind moments when Feist offers questions and formulations about the transnational circulation of socialist art, artistic influence, and the abstract qualities of critical writing on socialist realism. What emerges from this study is how Mun and others in the North Korean cultural orbit couched their critiques of modernist movements in semiotic terms, bemoaning, for example, abstraction’s rupturing of the signifier and signified—a breakage they characterized as stemming from and reflecting the psychic disorientation brought on by life in capitalist societies. And yet this charged rhetoric, frequently coupled with grainy, black-and-white reproductions of supposedly exemplary socialist realist works, gave rise to discursive and visual abstractions in turn, paradoxically setting loose a torrent of semiotic drift despite the authors’ efforts to rein in any and all ambiguities.

This angle allows us to rethink the presumed drive of socialist realism toward an ever-wider pool of referents and techniques originating outside of the socialist sphere. In the historical narrative presented here, the late 1950s no longer denotes a definitive breaking point, when those sympathetic to modernist currents won out over the Stalinist hardliners. Although concentrated on the terms and conditions of mid-century socialist realism, the stakes of this intervention extend to the field of modern and contemporary art history at its broadest. I show how the international circulation of and commentary on socialist realist art posed alternatives to the twin poles of formal innovation and critique—those totems associated with avant-garde practices that have long been taken for granted as defining any worthwhile artist’s creative outlook.

Intuiting Socialist Realism in Black and White

By the time The Art of Socialist Countries opened in 1958, developments in the North Korean art world had anticipated, if obliquely, several of the guiding maxims Feist would offer in Principles and Methods of a Marxist Kunstwissenschaft. Feist states at the outset that the framework he is concerned with does not privilege the “historically uneven development” of art production in different cultural contexts over time, but instead foregrounds “the mutual learning of peoples from one another, the ability of all people to achieve greatness, and the fundamental equality of creative potential in different peoples.”9 As evidence of this underlying equality, he points to the adoption of realist artistic strategies in places where such a stylistic turn might have seemed improbable. He names specifically “the Asian region of the Soviet Union” and “the young nation-states of the Arab world,” stressing how in these contexts artists had been “restricted for centuries to ornamental arts and crafts due to economic and social backwardness and the Islamic prohibition of images.”10 And yet they still came to adopt and advance realist aesthetics, thereby facilitating the international expansion of socialist realism. For Feist, such achievements suggest a creative element that escapes any interpretive framework that would insist upon a neat reduction of stylistic proclivities and iconographic programs to contingent national identities. Feist thus reaches for an art historical lens open to countenancing recursive phenomena as opposed to reading artistic forms strictly in terms of cultural difference. Realism, in his examples, serves as a plane of equivalence on which the singularities of discrete cultural practices are acknowledged without checking the greater prospects of transnational solidarity. While it would not be difficult to unfurl the Orientalist impulses that linger in Feist’s language and argument, it is perhaps more profitable for our purposes to examine how this lexicon of cross-cultural exchange and equality mirrored the discursive tides that swept through North Korea’s burgeoning artistic community in the 1950s.

Upon the founding of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK, North Korea’s official designation) in 1948, a crucial question emerged: how could the reservoir of Korean artistic heritage through the ages be reinterpreted and deployed to complement the recently instituted model of socialist realism? North Korean artists and critics had come to know socialist realist aesthetics through the experiences and examples shared by Soviet, Chinese, and Eastern European artists following the division of the peninsula in 1945. Seeking a synthesis of modern socialist art and Korean traditional aesthetics, they aimed to devise a distinctly national form that would still adhere to the techniques of figuration and modeling that were taken as foundational to the method of socialist realist representation.11 Against this backdrop, transnational engagement of the type that Feist would celebrate presented itself as a necessary and consequential aspect of art production, education, and discourse in the early years of the North Korean state. Exposure to established models of socialist realism was recognized as essential to the process of founding a workable system of socialist art appropriate for the conditions and contingencies that defined North Korea’s national identity and political reality.

If the sharing of art objects and aesthetic ideas between fraternal socialist countries was, on one level, an amorphous aspiration of socialist internationalism, it was also worked out in blunt, practical terms in a series of agreements on economic and cultural exchange that North Korea drew up with countries throughout Eastern Europe in the late 1950s. The details of these pacts varied in each case. For example, while the agreements with Bulgaria and Romania recommended field trips by prominent cultural figures and the translation of pivotal literary works, the agreement with Hungary stressed the importance of staging exhibitions in order to promote each other’s cultures.12 As a result of these formal and quantifiable commitments, displays of contemporary works by North Korean artists were regularly shipped abroad, and multiple exhibitions of art from fraternal socialist countries were staged in the North Korean capital.13

By turning to the exhibitions of international socialist art that took place in Pyongyang, we are able to glimpse the range of influences that shaped the trajectory of North Korea’s search for a national brand of socialist realism. I use the term “influence” advisedly here, as it features prominently in Feist’s essay as a concept in express need of qualification. Influence, in Feist’s formulation, entails an “active process on the part of the adopter” rather than “the irruption of foreign matter into an inert vacuum.”14 This active attitude toward imported forms and ideas had become a crucial point of emphasis in North Korea following a speech that North Korea’s leader, Kim Il Sung, delivered to the country’s writers and artists in 1951. Addressing the question of “what we should inherit from the past and how we should use it,” Kim proclaimed that creative workers “must take over and develop those things that are genuinely of the people and cast aside whatever is unscientific and vulgar.”15 In addition to mining national traditions, this effort would extend to “[studying] that which is excellent and progressive in the literature and art of the Soviet Union, China, and other People’s Democracies, thereby enriching our national culture still further.”16 While no doubt typical of Kim’s harangues in terms of its language and tone, we glimpse in this excerpt how Kim remained in lockstep with a wider discourse in the socialist world. For Kim, participating in artistic exchange with fraternal socialist countries was a vital step in North Korea’s effort to define its own national style through which to represent socialist content.

In light of Kim’s imperative, artists and critics in North Korea assumed a heavy mantle. Even the act of drafting a short review of an exhibition of Eastern European art constituted a high-stakes endeavor in the grand quest to sift through the manifold instantiations of socialist realism that had germinated abroad and discern which aspects should be assimilated locally in North Korea. Published reviews of such exhibitions quickly took on a standardized format. Working within the space of only one or two pages, the authors of these texts strategically selected artworks that could be celebrated for their high ideological merit and technical mastery, largely avoiding even subtle criticism of the contents on view. Moreover, given the diplomatic function of many of these exhibitions, the reviews were padded with copious lines of encomiastic bombast affirming the supposedly robust ties between North Korea and the particular country represented in a given exhibition. But amidst such buoyant lip service, insightful moments surface in which we are granted indirect access to the precarious working process that was involved in subjectively intuiting the criteria of legitimate socialist art at a time when even the tacit and nebulous guideposts associated with the art of the Stalin era were rapidly falling away.

One striking feature of North Korean art discourse that comes to light in such reviews is that not all variants of Western modernism were dismissed outright by North Korean critics in the 1950s. When, for instance, Pyongyang hosted an exhibition in May 1959 of reproductions of Hungarian paintings from the nineteenth century to the present, the critic Kang Ho noted how “Western art of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries generally followed French trends, and Hungary likewise followed this path.”17 While Kang’s readers might have expected a trenchant reproach of any concessions to the canon of Western art, the critic in fact went on to authorize certain branches of modernist painting, at least as they were taken up subsequently by artists of socialist countries like Hungary. Mentioning Édouard Manet and Claude Monet by name, Kang relates how Hungarian painters such as Károly Ferenczy (1862–1917) had embraced the techniques of impressionism and combined them with lessons taken from Hungarian predecessors such as the realist painter Mihály Munkácsy (1844–1900). Far from resulting in the corruption of genuine socialist art, Kang holds that Ferenczy’s aesthetic amalgam constituted a veritable breakthrough in the Hungarian art world.

It is useful here to cast a sideways glance and consider that impressionism had begun to be reintroduced to the Soviet museum-going public in the 1950s, with works by Edgar Degas, Monet, and Pierre-Auguste Renoir appearing, for example, in the inaugural exhibition at the Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts in Moscow when it reopened as a museum of European art in 1954. Yet the virtues of impressionism remained a subject of ongoing debate among Soviet art critics, with those on the conservative side dismissing the movement as formalist and therefore degenerate.18 As exemplified by Kang’s review, in comparison to their Soviet counterparts, North Korea’s art writers hardly amounted to the most severe of communist critics when it came to the subject of Western modernism. I raise this point because it shows that one cannot simply write off the seemingly anachronistic views that Mun Hak-su would express at the conference for The Art of Socialist Countries as the mindless recitation of draconian cultural policies enforced by a totalitarian state. Rather, a nuanced take on modernism had arisen in North Korea in which certain stands of Western art could, in select circumstances, be endorsed without relinquishing a firm allegiance to the established conventions of socialist realism.

That said, much as in the Soviet Union, this relative receptivity to specific modern art movements in North Korea did not carry over to examples of non-figural abstraction. The biggest fault of this categorically bourgeois device was that it foreclosed any possibility of a coherent narrative. Socialist realism had, after all, been conceived from its inception as a practice that would strive for clarity and concision in its delivery of ideologically correct content. When dealing with exhibitions of Eastern European art, one of the safest ways in which North Korean critics communicated this value was by underscoring an inseparable relationship between visual art objects and corresponding literary texts. Such was the strategy adopted by an anonymous author who, in 1958, assessed an exhibition in Pyongyang that featured some one hundred examples of Romanian paintings produced over the past decade. In the review, the writer highlights the painter Corneliu Baba (1906–97), an artist who had come of age and made a name for himself in pre-communist Romania, and who subsequently aligned himself with contemporary realist art.19 At first glance, Baba’s representation in the exhibition might have seemed underwhelming, consisting of only a small drawing in colored pencil. Titled Mitrea, the drawing depicted the main character of a 1949 socialist realist novel, Mitrea Cocor, by Mihail Sadoveanu (1880–1961), for which Baba had provided the illustrations. Given that the work was not reproduced with the North Korean review, we can only guess that the drawing on display was an initial sketch for one of the book’s plates. In any case, the reviewer singled it out as evidencing “the maturity of a painter who opened a new stage in the field of portrait painting”—this principally because, in the depiction of the main character, “the peasant awakeness [sic] towards the new, true life was vividly represented.”20 For the reviewer, this indicated that while Baba’s technique was rooted in “the mastery of the old painters,” he had also immersed himself “in the spirit of the times.”21 In the absence of any detailed description of the drawing, much less a reproduction of the work, the primary lesson to be gleaned concerns content and process rather than form. To throw oneself into the reality of contemporary socialism, the reader infers, entails seizing upon the already-honed formal methods of sanctioned masters and applying them to subject matter befitting the newly emerging horizon of socialist life as portrayed through the kinds of narrative structures characteristic of socialist realist literature.

When it came to reproducing representative images alongside reviews of Eastern European art, graphic art proved to be one of the few visual media that could be convincingly reduplicated with North Korea’s rudimentary black-and-white printing capabilities. Unlike the bulk of socialist realist oil paintings, for example, woodblock prints retained their legibility in North Korean publications, structured as they are by sharp contrasts between saturated black ink and white paper. Fortuitously, graphic art comprised a sizeable portion of the works sent by Eastern European countries to North Korea, these prints being lightweight and easier to transport than paintings or sculptures. Moreover, the inherent reproducibility of print media meant that there was little risk in shipping examples of such works to a country still floundering in the ruinous aftermath of a devastating war.

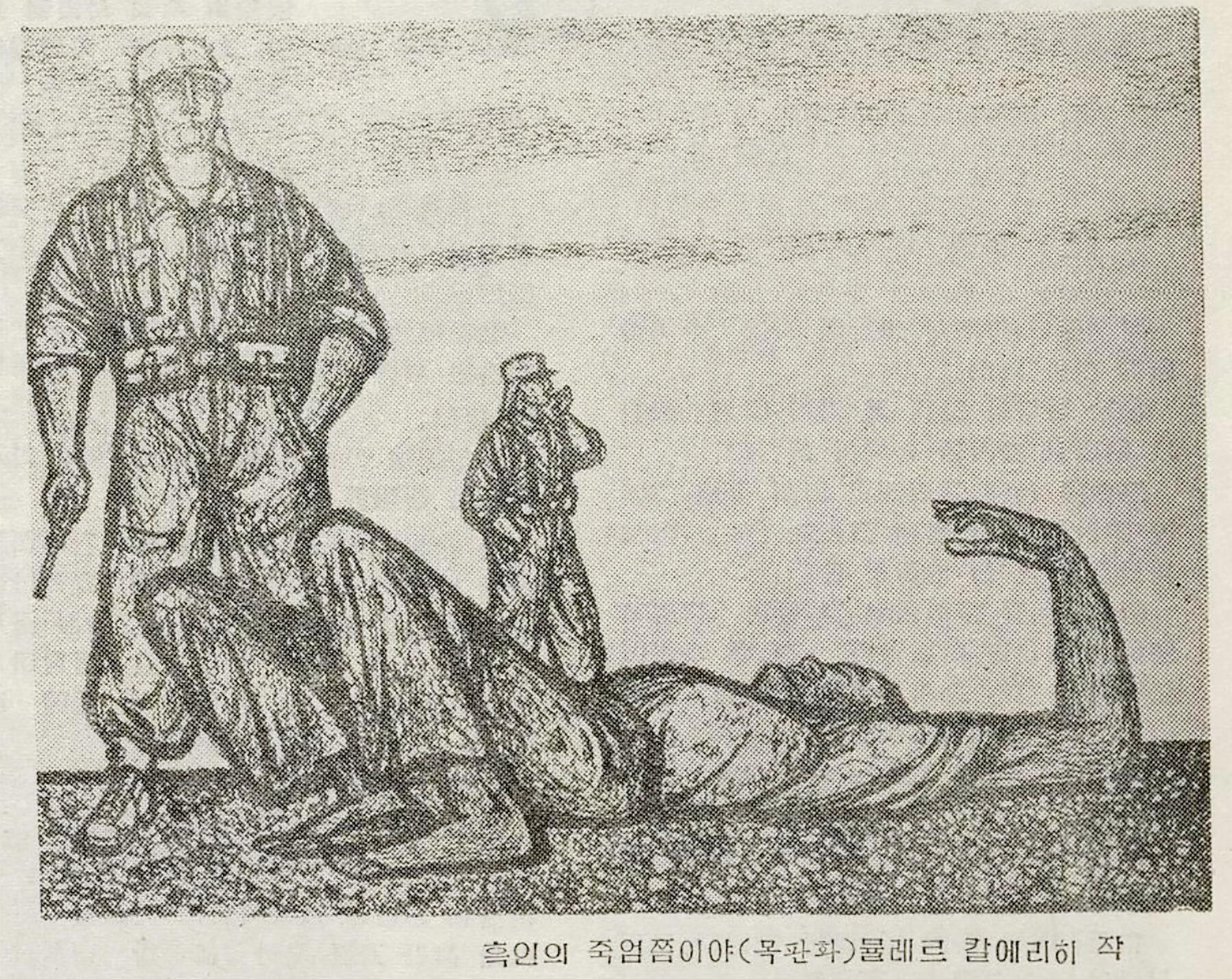

On October 13, 1959, an exhibition of graphic art from East Germany opened on the fourth floor of the National Art Museum in Pyongyang in celebration of the tenth anniversary of the establishment of the German Democratic Republic. The event’s diplomatic potency was on full display as officials from the East German embassy attended the opening ceremony, one of whom delivered a speech emphasizing the shared experiences of the GDR and the DPRK as parts of divided nations seeking appropriate paths to reunification.22 An additional point of solidarity could be identified in the commitment of the two countries to anti-colonial resistance movements across the globe. This much was underscored by a series of three prints concerning Algeria that were reproduced alongside a brief description of the exhibition in Chosŏn misul [Korean art], North Korea’s primary art serial at the time. An especially poignant example is culled from a body of work that the graphic designer and painter Karl Erich Müller (1917–98) had been pursuing since at least 1957 on the theme of the plights endured by Algerians under French colonization. Müller captured everything from the toil of life on plantations to direct physical violence at the hands of the imperialists. The work featured in Chosŏn misul takes the latter thematic strand to its disturbing conclusion, showing a dark-skinned man lying on the ground before a towering white agent in military regalia. As the latter wields his gun, another officer saunters nonchalantly in the background. Given the generalized depictions of the figures and the nondescript environs of the scene, it would be difficult for viewers to place this image squarely in the context of Algeria without being informed of its specificity in the accompanying write-up. But this seems to be the point: that the structural design of the image could apply to any number of contexts in which those in the position of the subaltern find themselves caught beneath the weight of imperialist initiatives. The Korean title ascribed to the print suggests as much, translating literally as “A Black Man on the Verge of Death” (Fig. 1).23 Given only the title and the image, one could easily read the print as a representation of violence against African Americans, whose experiences would soon become an object of great attention in East Germany with the rise to prominence of Paul Robeson upon his visit to the GDR in October 1960.24

Rather than communicating singular specificities, Müller’s Algerian print hinges on the visual dichotomy of black and white integral to the woodblock print format. Müller plays up this opposition to set at odds the white oppressors, positioned in emphatically vertical postures, and the dying dark-skinned man lying in a horizontal state. The juxtaposition even extends to the environment, the sharp particles of gravel that comprise the man’s terrestrial deathbed contrasting with the smooth patches of white paper that denote the unfittingly serene sky.

As a counterexample to the legibility that was retained in the reproduction of Müller’s print, we need only turn to the first few pages of the same Chosŏn misul issue, where an article titled “Let Us Learn from Soviet Art” provides an overview of Soviet paintings and monuments on the occasion of the 42nd anniversary of the October Revolution.25 Among the reproductions included in the article is Boris Ioganson’s 1933 oil painting, Interrogation of the Communists (Fig. 2–3). On one level, the subject matter of Ioganson’s work caters to the same dualistic logic that structures Müller’s print, staging as it does an encounter between White Guards and two proletarian “Reds” who have been commanded into an interrogation room. It is as if Ioganson had tried to convert the Suprematist geometric abstraction of El Lissitzky’s canonical 1919 lithograph, Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge, into the language of realism while retaining the binary opposition built into El Lissitzky’s title and visual configuration. Despite this overarching dyad, Ioganson’s painting has the viewer confront significant ambiguities. Natalia Budanova points out, for example, how the gendered depiction of the two communist protagonists troubles any clear distinction between male and female subjects, which was otherwise demanded under the epistemological worldview of Stalinist totalitarianism.26 In Ioganson’s painting, the two revolutionaries are garbed similarly. Heroic masculinity thus emerges as a guise to be worn not only by men but also by women, who are thus given license to step into the realm of androgyny.

In the context of the article in the North Korean journal, the work is placed in a narrative of Russian revolutionary art that begins with the formation of the Association of Artists of Revolutionary Russia (AKhRR) in 1922. This is predictable given that AKhRR was seen as the progenitor of the brand of socialist realism that would be mandated under Stalin following the dissolution of all artistic groups in 1932 and the establishment of the Artists’ Union of the USSR. With no mention made of the competing art alliances that advocated for other directions, Ioganson’s painting is introduced as evidencing the headway made in Soviet painting during these years. It is perplexing that the author makes no attempt to describe the picture, especially given that it occupies such a primary place in the layout of the article. Rather, the reader gets the sense that no words are necessary. “In the field of painting, the achievements of this period can be cited ad infinitum,” we read, “but it is sufficient to point out only Ioganson’s ‘Interrogation of the Communists’ (1933) and ‘At the Ural Factory’ (1937).”27 An immense communicative weight thus comes to rest upon the reproduction of the work.

In the black-and-white representation of the painting in Chosŏn misul, ambiguity is pushed far beyond the discrepancy Budanova identifies between official policy and sartorial codes. In some areas, the work even appears to border on non-representational abstraction. The contours marking the edges where the walls of the interrogation room meet the floor, for example, are lost in an indeterminate field of grey. This only accentuates the already curious spatial orientation of the painting, as the angling of the white designs on the carpet causes the room to appear as if it is situated on a steep slope, the communist prisoners about to be pulled by gravity into collision with the seated officer. All the while, the man who has ushered the revolutionaries into the room, and who stands menacingly behind them in the painting, has entirely disappeared into the charcoal-like blur that envelops the scene. Likewise, the standing guard to the right of the principal interrogator, while still partially visible, becomes a headless mass of jumbled limbs and weaponry, recalling Italian Futurist takes on velocity and violence.

What were readers to make, then, of the disjunction between the self-evident clarity attributed to the image in the written text and the baffling muddle of visual distortions printed alongside it? In light of this example, when Feist writes in his essay of the “art historical relevance of not only the mass distribution of reproductions that make accessible the entire artistic heritage and the latest inventions to potentially every artist and every audience at any time, but also of the far, fast, and frequent travels of both viewers and works of art,” we would do well to remain cognizant of the material forms of such reproductions.28 As with the North Korean reproduction of Ioganson’s masterpiece, such representations oftentimes had only a tenuous relationship to the artworks they were meant to stand for, becoming unique specimens in their own right and signifying independently of any original source.

This decoupling of signifier and signified—the reproduction and the oil painting—ironically hits on the North Korean state’s apprehension over abstraction. The assumption was that socialist art should entail an unambiguous marriage of image and word, whether that be an artwork and its title, or an illustration and a corresponding literary text. The danger of any fissure between these dimensions would constitute the basis of the case presented by Mun Hak-su at the Moscow symposium. As we will see presently, Mun’s stance set him apart from the majority of representatives at the meeting, who advocated for an open-ended definition of socialist realism. At the same time, his propositions turned a blind eye to the many unruly representations of socialist art circulating in North Korea through crude conduits that, in the context of a forceful pursuit of lucidity, could register only abstractions in terms of formal and artistic qualities, as well as political and ideological positions.

Abstracting from Mun Hak-su’s Moscow Salvo

When Mun took the floor at the Moscow symposium, he was quick to reiterate the value of international cultural exchange and the indispensable duty of socialist artists from different nations to study one another’s developments and directions. “Artists of Korea are paying keen attention to this international art exhibition in Moscow,” Mun proclaimed, “and are working hard to learn from all of the advanced achievements.”29 An anonymously penned introductory passage that accompanied Mun’s speech when it was reprinted in Chosŏn misul in May 1959 magnified this sense of mutual engagement. The author employs overtly affective language, declaring, “[t]he artworks of socialist countries have already become a major force in accelerating socialist construction,” and that “by participating in the exhibition, artists of brotherly countries have become more intimate with one another, and have come to know more about one another.”30 What stands out is how the writer does not cite the exhibition as cold empirical confirmation of socialist internationalism’s triumphs, as one might have expected given Kim Il Sung’s aforementioned directive that, in assessing the merits of international art, cultural workers should be principally concerned with jettisoning the “unscientific and vulgar.” Instead, the reader is told that the exhibition’s effects transpired chiefly at the level of emotive response. The writer continues, for instance: “And in the struggle for socialism and advanced art, it made us feel the unity and solidarity of our ranks more clearly.”31 In these lines, the inexorable force of socialist construction is married to delicate intimacy among international constituents, and the clarity of one’s role within the system of socialist internationalism is rooted in a subjective feeling of camaraderie.

I pause over this introductory passage because it instances how the espousal of socialist realism in North Korea—and the attendant mandate for content that could be clearly codified and made to operate as an ideological tutorial for viewers—was simultaneously set within a matrix of subjective experiences that were difficult to pin down but were nonetheless upheld as essential to socialist art. Just what was it about The Art of Socialist Countries that purportedly elicited sentiments of tenderness and affection amongst the motley congregation of artists and critics who had journeyed to Moscow to see the exhibition and participate in the symposium? Because it escapes any easy answer, this question demonstrates how deeply discourse on socialist realism in North Korea was shot through with conceptual abstractions—not least of which were the unnamed Chosŏn misul penman’s hazy references to feelings of close companionship. Such abstractions likewise haunted Mun’s argumentation, even as he condemned virtually all non-representational artistic devices.

Although Mun’s Moscow speech began by following a congratulatory and largely predictable course, it took a sudden turn when he alleged that “in recent years, Korean artists could not but direct their attention to the fact that formalist influences—in particular those associated with Cubism, Fauvism, and abstraction—have begun to appear in the work of some artists of brotherly countries.”32 Here, Mun speaks in a critical tone that was altogether absent in reviews of Eastern European socialist artworks exhibited in Pyongyang. Mun was no doubt on familiar terms with the list of modernist “–isms” he cited, as he had belonged to a group of Korean artists who, in the Colonial period (1910–45), studied at and graduated from the Bunka School in Tokyo. This institution, in the words of art historian Kim Young-na, promoted a “liberal creative atmosphere” and led Mun to produce works that Kim compares to Mark Chagall’s flirtations with Cubism, Symbolism, and Fauvism.33

A native Pyongyangite, Mun elected to remain in North Korea following the division of the peninsula in 1945.34 Upon North Korea’s adoption of socialist realism during the years of Soviet occupation that preceded the Korean War (1950–53), Mun honed his style in line with lodestars such as Jean-François Millet and Eugène Delacroix, whose works were, in early North Korean art discourse, assimilated as important precedents to socialist realism.35 As he ascended within the ranks of the North Korean art world, he was among those tasked with advancing the most elevated genre in the socialist realist order: the leader portrait.36 Mun’s rising stature and reputation in North Korea by the late 1950s had thus carried him far from the dalliances of his early career—formal experiments of the kind he now publicly denounced in Moscow.

To illustrate the faults evidenced across certain sections of The Art of Socialist Countries, Mun pointed to the Polish painter Adam Marczyński (1908–85), one of a host of Polish artists who, in the post-WWII years, had turned to abstraction. That Polish artists had come to embrace abstraction fed into the Cold War cultural dynamics that defined the late 1950s. This became obvious when, just one month after the Moscow symposium, the US magazine Time published an image of the Polish artist Tadeusz Kantor standing before his much-celebrated 1958 abstract painting Alalaha. The accompanying article exclaimed: “Today, under the regime of Władysław Gomułka, Polish artists have burst irrepressibly from their cellars in an outpouring of expressionist and abstract canvases just as if a dozen years of Nazi and Stalinist suppression had never been.”37 As Jill Bugajski has shown, this episode was part and parcel of the US media’s widespread celebration of Polish abstraction as a refractory gesture against socialist realism in the wake of the Khrushchev Thaw.38 More than a passing phenomenon, this investment in applauding specific currents of Polish art led to a series of extraordinary efforts by American museums to bring Polish abstraction to New York and other American cities in the early 1960s. Doing so proved difficult, as the Polish government—in an effort to assuage strained relations with Moscow—had set an arbitrary quota on the percentage of Polish abstract works that could be exhibited publicly. Blue chip American institutions, including the Museum of Modern Art, thus resorted to makeshift maneuvers and off-the-book dealings to secure, for example, the set of paintings that would be exhibited in MoMA’s 1961 exhibition Fifteen Polish Painters. In some ways, this difficulty in securing the works augmented the perceived daringness of Polish artists who skirted the socialist realist mandate that still hung over the majority of socialist countries in Eastern Europe. Even if the momentum behind abstraction’s critical implications and formal innovations had waned in the New York art world by 1959, the adoption of these strategies by artists in the Soviet bloc was seen as concretizing the historical significance of non-representational visual forms associated with the various modernist “–isms” that Mun enumerated. Polish artists’ experimentation with these strategies seemed to affirm that abstraction could be mobilized belatedly as a critical force in socialist contexts that had to date insulated themselves from the innovations tied to Western modernism.

Regarding Marczyński’s work, Mun’s chief complaint turned on the scission between the titles of his paintings and their visual contents.39 Marczyński’s submissions to the exhibition bore the simplest of designations, such as “Spring,” “Lake,” and “Landscape.” And yet the corresponding pictures displayed scarcely any resemblance to the subject matter named in their titles. They offered little of the clear-cut impact that could be located in other national sections of The Art of Socialist Countries, such as those that had been singled out by none other than Kim Il Sung when he led a delegation of the Korean Workers’ Party to Moscow in January 1959. The North Korean media reported that, upon visiting the exhibition, Kim was seized by the portrayal of fighters for national freedom and independence in Albanian oil paintings, Vietnamese prints, and Chinese ink paintings.40 By contrast, Mun described Marczyński’s paintings as presenting “abstract illusions at odds with what humans feel in time in response to specific natural phenomena.”41

Of interest is how Mun’s disparagement veered toward the register of the emotive. What he found deserving of critique was not only that Marczyński’s images failed to congeal as recognizable references to objects in the world—say, a lake or spring foliage—but also the fact that they neglected to arouse the appropriate feeling of an encounter with such scenes. In Mun’s judgment, it was not enough for socialist art to achieve an adequate level of representational likeness to a given object. Rather, he insisted upon an intangible dimension to socialist realism—one that, while tied to conventions of figuration, lies principally in the affective experience of the viewer who encounters the work of art. In both abstraction and socialist realism, then, subjective experiences were at issue. But, as Mun would emphasize, while socialist realism properly oriented itself toward reality by tapping into the universally shared feelings of the proletariat, abstraction privileged the subjectivity of a single artist, resulting in a congeries of illusory visuals disengaged from the revolutionary course of history. It was particularly lamentable, for Mun, that the delusional impressions wrought by abstraction had, over the past thirty years, been projected outward by critics and commentators as broadly characterizing “the sense of the twentieth century.”42 While such works might well index the contradictions of capitalism and the psychic turbulence that inevitably snowballed under its grip, they failed to acknowledge the contrastingly glorious trajectory of life under socialism.

Mun must have felt that, in voicing his stance on this score, he was positioned on the outside of a community of artists and critics committed to redirecting the course of socialist art. A summary of the symposium printed in Chosŏn misul, which followed the transcript of Mun’s speech, suggests as much. It details how Juliusz Starzyński, the head of the Polish selection committee for the exhibition, “continued to maintain that experimental art forms—even abstract art—could serve as a valuable wellspring for artists as they devise new formal methods.”43 Starzyński went as far as to declare that it was the artist’s “right” to draw from examples of experimental art. Although Starzyński was the most outspoken of the participants on this point, it was not just a small contingent of Polish radicals who were pressing for a more expansive conception of socialist art that would extend beyond the bounds of realism. Summarizing the Moscow symposium, Jérôme Bazin explains: “Since the Stalin era, when it was seen as the expression of a socialist reality that would brook no questioning, realism had lost some of its assurance and had become more uncertain. At the Moscow conference, Soviet artists stated that the socialist realism of Zhdanov’s day had been a dead end because it failed to create a feeling of reality. They argued that it was vital to look for other paths.”44 Here, we again come upon an emphasis on emotional responses associated with reality, except that, unlike Mun, Soviet artists maintained that the pursuit of such impressions would require a wider repertoire of stylistic devices than had yet been admitted in the canon of socialist art.

This ascendant attitude at the conference was thus at odds with what not only Mun but other leading North Korean artists who saw the exhibition in person had expected to encounter. A short article in the April 1959 issue of Chosŏn misul announced the departure of a team of eleven artists who left for Moscow with Mun in order to embark upon a field trip to Soviet museums and cultural sites in Moscow and Leningrad. The article anticipates that the journey would “undoubtedly contribute greatly to the development of Korean art” in that it would afford an opportunity to “learn from the Soviet Union’s achievements in the field of art—a result of the artistic and literary policies of the Communist Party and the government, and the advanced, creative, economic cooperation of socialist countries.”45

North Korean artists’ attachment to the criteria that had shaped realist painting during the Stalin years could only have reinforced Soviet cultural producers’ widespread association of North Korea with dreadfully strict artistic mandates—a perception that had taken hold as early as the 1940s. Tatiana Gabroussenko describes how, during the late 1940s, “a visiting group of Soviet writers and artists tried to persuade their North Korean colleagues not to write exclusively about the Party and Kim Il Sung but to extol ‘external subjects such as love or flowers for a change.’”46 She goes on to explain how Soviet writers strengthened their attempts to convince their Korean counterparts to “humanize” their literary works in the mid-1950s, particularly after the Second Soviet Writers’ Conference in 1954, during which Soviet writers found themselves reproached to more freely express their individual feelings in order to sap the over-bureaucratization of the literary field.47

What happened in Moscow in 1959, then, nuances the dynamics of cultural relations between the Second and Third Worlds theorized by Rossen Djagalov, for whom the artists, writers, and audiences of postcolonial nations creatively modified or otherwise selectively adhered to the official aesthetic grammars transmitted through the channels of Soviet cultural diplomacy.48 In Djagalov’s delineation, the Third World presents as a range of forces that took established Soviet cultural forms in new and unanticipated directions through imaginative appropriation and reception. As we have seen, however, in the case of North Korea in the late 1950s, the inverse fell out. Mun dared to contend that the contemporary art of socialist internationalism needed to conform more faithfully to received Soviet conventions from which even representative Soviet artists were now distancing themselves.

For Mun, his was not entirely a lost cause. Despite abstract abominations like Marczyński’s, he could find ample evidence throughout the exhibition of artists who displayed a debt to the core formal and ideological planks of socialist realism. In the Polish section, he notes, sculptors and graphic designers had most meritoriously met the charge of socialist realism’s essential mandates, leaving him hopeful that even Marczyński would, in time, turn down the proper path of socialist realism.49

In presenting such an outlook to readers on the North Korean home front, the Chosŏn misul write-up on Mun’s experience in Moscow generated a series of disjunctions between image and text that paradoxically mimed the disconnect Mun diagnosed between Marczyński’s titles and painted forms. Following the transcript of Mun’s address, the article provides summaries of the speeches given by the various attendees present at the symposium, including the passage from Starzyński quoted above. It is not until the end of the piece that the reader is informed in fine print that the preceding article is a direct translation of a text that had appeared in the Soviet newspaper Sovetskaya kultura. And yet clearly the entirety of the article was not culled from that source, which would have had no reason to foreground Mun Hak-su above all other delegates. This ambiguity over the origin and standing of the printed text in the Chosŏn misul report is given added intensity by the specific images chosen to represent each country’s contribution to the exhibition. These were presumably meant to provide North Korean readers with a visual demonstration of the most laudable examples of socialist realism that could be found across the discrete installations. One can assume as much because in the majority of cases the selected images are not referenced at all in the corresponding summaries, discounting the idea that they might have been chosen for the purpose of supporting the particular arguments set down by the individual delegates.

Names already familiar to us populate the article. For East Germany, we find a print by Karl Erich Müller taken from a series translated in Korean as “The Wrong Idea of Glory” (Fig. 4).50 The work packs the same immediacy as Müller’s aforementioned Algerian series that would soon after be exhibited in Pyongyang. Indeed, its composition echoes the image of the dying man we previously studied. In this case, a Nazi official points a gun to the neck of a kneeling and cuffed woman while bystanders stare on complacently in the background. In these pages of Chosŏn misul dedicated to the Moscow exhibition, the legibility retained in the reproduction of the woodblock print again stands out compared to works in other media, where the content denoted in the titles is barely discernible on a visual level. Take, for instance, an oil painting by the German artist Gottfried Richter (1904–68) titled Before the Demonstration, where we are given a bird’s-eye-view of a crossroads surrounded by towering buildings (Fig 5). Human figures below can be intuited only by crude strokes of paint that, in the reproduction, give no sense of the figures’ physical constitution, their orientation in space, or the cause for which they swarm the streets. They are lost altogether in the upper register of the reproduction, where the dark shadows of the buildings wash out any subtleties that might have subsisted in the oil painting. With the architectural structures reduced to only three tones of white, grey, and black, the environs of the scene appear to either collapse or melt away, in turn warping any sense of naturalistic spatial perspective. Detached from any secure relation to the protest signaled by the title, the work foregrounds a free play of visual forms as the figurative image dissolves into abstractions. In the context of the journal, the image is printed such that it abuts a text recounting an East German delegate’s accusation that “the enemies of socialism in West Germany are trying to maintain an ideological position that has no connection to us [in East Germany in the field of art. They are openly using art as a weapon to confuse public consciousness.”51 How, we might ask, was the scrappy reproduction of Richter’s painting to act as a representative antidote to the transgressions of the West German art world and its reckless pursuit of the confusing visual schemes of Western modernism?

In toto, the Chosŏn misul article featuring Mun’s speech gives us a run of axiomatic assertions about socialist art’s anchoring in universal feelings of reality shared by the proletariat; a strong condemnation of abstraction’s decoupling of signifier and signified; a decontextualized translation of a Soviet summary of the symposium; and a constellation of images with no explicitly stated correlation to the words they sit adjacent to. And all of this is condensed into the span of seventeen pages, two of which are taken up by single images. The reading and viewing experiences initiated by this curious object thereby link us back to a suggestive moment in Feist’s Principles and Methods of a Marxist Kunstwissenschaft where he engages in self-conscious reflection, wrestling with his own apprehension over the very format of his undertaking and, in particular, the relative concision of his articulations. Key for our purposes, he worries that the “brevity of [the text’s] theoretical generalization” could make the whole thing “seem too abstract.”52 Indeed, he notes, “in many cases, there is only one sentence where an entire essay is needed as proof.”53 More than a happenstance invocation of abstraction, Feist immediately follows this admission with a peculiar visceral description of the effect his grand generalizations might have on the reader: “Necessarily stripped of the flesh and blood of historical diversity and vivid examples, it may initially seem just as frightening as any skeleton.”54 Feist imagines his readers coming up against the world of the dead, as opposed to the immanence of reality in its revolutionary development. Moreover, the audience of the text is presumed to experience shock at this encounter, an anticipation that reprises the agendas of so many avant-garde manifestos in their drive to shake viewers out of complacency through collisions with all things uncanny or otherwise unintelligible. Feist’s association of brevity with abstraction allows us to see yet another way in which North Korean discourse sponsoring tried and true exemplars of socialist realism gave itself over to the very formal qualities it decried—to abstraction.

Conclusion

What comes out of this admittedly unusual treatment of North Korean reviews of exhibitions and reproductions of Eastern European artworks in conjunction with Feist’s essay is an impetus to approach socialist realist art from an ontological rather than an epistemological basis. This means to cease being satisfied with merely rehashing the mandates handed down to artists by a given socialist state, as if these orders were sufficient to explain discrete works of art. Rather, it entails grappling with such questions as: “what have been the effects of socialist realist artworks and the circuits through which they traveled?” and “what might socialist realism have been capable of?”

Feist emphasized that this shift in the grammar through which socialist realism is approached amounted to more than an academic exercise when he reflected on the cultural policies of the GDR in a conversation with Gabriele Sprigath in 1975. On this occasion, Feist portrayed socialist realism as responding to contingent tendencies and beliefs among the proletariat, as opposed to a timeless set of injunctions. He recalled, for instance, how at one point, “the benchmark, even for the socialist worker, was that he should know his Beethoven and his Goethe as well as or better than the educated citizen of the nineteenth century, an idea that represented a survival of the bourgeois conception of culture and the tradition of the workers’ cultural associations from the pre-socialist period.”55 Therefore, Feist explains, “it was quite right to start by shifting the focus of attention among the artist fraternity and the public at large toward the completely unknown tradition of revolutionary proletarian art in order to help attain new artistic perspectives.”56 The policies behind socialist realism here appear as something like balancing weights that are to be adjusted constantly according to the activities of artists and the dominant perceptions of the working class—never set in stone, constantly in flux. It is this volatile quality of socialist realism that was put on full display in North Korean critics’ awkward reception of Eastern European art and in the precarious—and at times downright indecipherable—visual reproductions of representative works that flooded Pyongyang. Despite the significance attributed to the shocking Polish entries to The Art of Socialist Countries, in the late 1950s, socialist realism did not need Western modernism to become abstract. Socialist realism’s fundamentally abstract qualities already amounted to its biggest skeleton in the closet.

- [1] Cited in: Susan Reid, “The Exhibition Art of Socialist Countries, Moscow 1958–9, and the Contemporary Style of Painting,” in Susan Reid and David Crowley, eds., Style and Socialism: Modernity and Material Culture in Post-War Eastern Europe (Oxford: Berg, 2000), 106.

- [2] Jerome Bazin [Jérôme Bazin], “The Geography of Art in Communist Europe: Other Centralities, Other Universalities,” Artl@s Bulletin, vol. 3, no. 1 (2014), 45.

- [3] Jérôme Bazin, Pascal Dubourg Glatigny, and Piotr Piotrowski, “Introduction: Geography of Internationalism,” in Jérôme Bazin, Pascal Dubourg Glatigny, and Piotr Piotrowski, eds., Art Beyond Borders: Artistic Exchange in Communist Europe (1945–1989) (Budapest: Central European University Press, 2016), 10.

- [4] Matthew Cullerne Bown, Socialist Realist Painting (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998), 390.

- [5] Reid, “The Exhibition Art of Socialist Countries,” 101–32.

- [6] See, for example: Jérôme Bazin, Sándor Hornyik, Tihomir Milovac, and Xawery Stańczyk, “Narratives and Places of Cultural Opposition in the Visual Arts,” in Balázs Apor, Péter Apor, and Sándor Horváth, eds., The Handbook of COURAGE: Cultural Opposition and Its Heritage in Eastern Europe (Budapest: Institute of History, Research Centre for the Humanities, Hungarian Academy of Sciences, 2018), 241–66. The authors invoke the binary division between socialist realism and alternative art practices when examining institutions throughout Eastern Europe that were involved in collecting and displaying “abstract and subversive art” (248). A key example is the City Gallery of Contemporary Art in Zagreb (now the Muzej Suvremene Umjetnosti, MSU). It is presented as having, from its founding in 1954, advanced the mission of “establish[ing] a program policy based on the criteria and experiences of the pre-war historical Avantgarde, on opposition to ideologized culture and art (including post-war Socialist Realism), and on intensive internationalization and the opening up of space for the neo-Avantgarde experiment, which was a direct path to the idea of changing social realities” (248).

- [7] Eckhart J. Gillen stands as an exception among art historians when he argues for the continuity between Richter’s output in East and West Germany, at least through the mid-1960s. Gillen posits that the ironically termed “Capitalist Realist” pictures Richter produced in West Germany share with socialist realism “the use of photography as a mimetic form of representing reality” in addition to the notion that in each case Richter’s works appeared as “forms of propaganda for politics and for commodities, respectively.” Eckhart J. Gillen, “Painter without Qualities: Gerhard Richter’s Path from Socialist Society to Western Art System, 1956–1966,” in Christine Mehring, Jeanne Anne Nugent, Jon L. Seydl, eds., Gerhard Richter: Early Work, 1951–1972 (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2010), 65.

- [8] See Eva Cockcroft, “Abstract Expressionism, Weapon of the Cold War,” in Francis Frascina, ed., Pollock and After: The Critical Debate (London: Routledge, 2000), 147–55.

- [9] Peter H. Feist, Principles and Methods of a Marxist Kunstwissenschaft—Attempt at an Outline, trans. Tamara Golan and Felix Jäger, in Tamara Golan and Felix Jäger, eds., Selva 5 (spring 2024), 26–52, here 34.

- [10] Feist, Principles and Methods, 34.

- [11] North Korean artists and critics landed relatively quickly on the idea that ink painting provided a satisfactory solution to this problem. Ink painting, when combined with colored pigments, was seen as evincing a uniquely Korean aesthetic sensibility, and the medium could be calibrated to the kind of figurative representation demanded by socialist realism. See: Jisuk Hong, “Modernity in North Korean Art: Socialist Realism, Joseonhwa and Photography,” in Yeon Shim Chung et al., eds., Korean Art from 1953: Collision, Innovation, Interaction (London: Phaidon, 2020), 143–46. This gravitation to ink painting may have had its genesis in the artistic exchange made possible by socialist internationalism, as the training of ink painters in North Korea increased dramatically after an ink painting division was opened at the Pyongyang College of Arts under the guidance of Pen Varlen, a Soviet artist of Korean ethnicity who had journeyed to Pyongyang on several occasions and became a guiding figure as the country established an art system from the ground up. See: Young Ji Lee, “Building North Korean Art: Pen Varlen/Pyŏn Wŏllyong and Ethnic Networks amid the Cold War,” Art in Translation, vol.12, no. 4 (2020), 504–6.

- [12] Cited in Yi Chu-hyŭn, “1950nyŏndae huban pukhanmisurŭi tongyurŏpchŏnsiwa minjok misurŭi hyŏngsŏng” [North Korean art exhibitions in East Europe in the late 1950s and the formation of national art], Misul sahak yŏn’gu 305 (2020), 114.

- [13] Yi provides a useful table of seven such exhibitions that were held in Pyongyang between 1957 and 1959 featuring representative works from countries including Bulgaria, East Germany, Hungary, and Poland. See: Yi, “1950nyŏndae huban pukhanmisurŭi tongyurŏpchŏnsi,” 115.

- [14] Feist, Principles and Methods, 35.

- [15] Kim Il Sung, “On Some Questions Arising in Our Literature and Art: Talk with Writers and Artists, June 30, 1951,” in Works, vol. 6 (Pyongyang: Foreign Languages Publishing House, 1981), 343.

- [16] Kim, “On Some Questions Arising in Our Literature and Art,” 344.

- [17] Kang Ho, “Wenggŭriya hoehwa pokchep’um chŏllamhoerŭl pogo” [Report on an exhibition of Hungarian painting reproductions], Chosŏn misul (June 1959), 25–27.

- [18] Susan Reid, “(Socialist) Realism Unbound: The Effects of International Encounters on Soviet Art Practice and Discourse in the Khrushchev Thaw,” in Bazin, Glatigny, and Piotrowski, eds., Art Beyond Borders, 274–75.

- [19] “Rumanian Art Exhibition,” New Korea (February 1958), 48.

- [20] “Rumanian Art Exhibition,” 48.

- [21] Ibid.

- [22] “Togil kŭrahwik’ŭ chŏllamhoe” [Exhibition of German graphics], Chosŏn misul (November 1959), 35.

- [23] I have not been able to verify the German title given to the print by Müller. The title in Korean is Hŭginŭi chugŏmtchŭmiya.

- [24] Natalia King Rasmussen, “Friends of Freedom, Allies of Peace: African Americans, the Civil Rights Movement, and East Germany, 1949–1989” (PhD dissertation, Boston College, 2014), 68–106. Robeson was able to make the trip to the GDR only after having his passport returned to him by the US State Department, which had confiscated it in 1950 due to the activist’s forceful protests against the Korean War. See: Suzy Kim, “Land of the Oldest Travel Ban,” Adi Magazine, winter 2019, https://adimagazine.com/articles/land-of-the-oldest-travel-ban (accessed 5/4/2024).

- [25] Kim Ch’ang-sŏk, “Ssoryŏn misurŭl hyanghayŏ paeuja” [Let us learn from Soviet art], Chosŏn misul (November 1959), 1–6.

- [26] Natalia Budanova, “Utopian Sex: The Metamorphosis of Androgynous Imagery in Russian Art of the Pre- and Post-Revolutionary Period,” in Christina Lodder, Maria Kokkori, and Maria Mileeva, eds., Utopian Reality: Reconstructing Culture in Revolutionary Russia and Beyond (Leiden: Brill, 2013), 39.

- [27] Kim, “Ssoryŏn misurŭl,” 3.

- [28] Feist, Principles and Methods, 41.

- [29] Mun Hak-su, “Sahoejuŭi che kukka chohyŏng yesul chŏllamhoe ch’onghwa hoeŭiennŏ han t’orondŭrŭi yoji: Sahoejuŭi misulgwa hyŏnsil” [A summary of the discussions at the Conference of the Art of Socialist Countries Exhibition: Socialist Art and Reality], Chosŏn misul (May 1959), 7.

- [30] Mun, “Sahoejuŭi che kukka chohyŏng yesul chŏllamhoe,” 7.

- [31] Ibid. Emphasis my own.

- [32] Ibid., 9.

- [33] Kim Young-na, 20th Century Korean Art (London: Laurence King, 2005), 135–40.

- [34] Jane Portal, Art Under Control in North Korea (London: Reaktion, 2005), 128–29.

- [35] Min-Kyung Yoon, “Visualizing History: Truthfulness in North Korean Art,” Journal of Korean Studies, vol. 25, no. 1 (2020), 182.

- [36] Important examples include Mun’s two versions of Mass Gathering to Welcome the Return of the Great Leader of the Revolution, Comrade Kim Il Sung, which he painted in 1953 and 1961 respectively. These are reproduced in: Frank Hoffmann, “Brush, Ink and Props: The Birth of Korean Painting,” in Rüdiger Frank, ed., Exploring North Korean Arts (Nuremberg: Verlag für moderne Kunst, 2011), 160.

- [37] “Art: Adventurer in Poland,” Time, vol. 73, no. 14 (April 6, 1959), 81.

- [38] Jill Bugajski, “Tadeusz Kantor’s Publics: Warsaw – New York,” in Peter Romjin, Giles Scott-Smith, and Joes Segal, eds., Divided Dreamworlds? The Cultural Cold War in East and West (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2012), 53–72.

- [39] Mun, “Sahoejuŭi che kukka chohyŏng yesul chŏllamhoe,” 9.

- [40] “Taep’yodanŭi mossŭk’ŭba ch’eryu: sahoejuŭi che kukka chohyŏng yesul chŏllamhoerŭl ch’amgwan” [The delegation’s stay in Moscow: Visiting The Art of Socialist Countriesexhibition], Rodong sinmun, January 27, 1959.

- [41] Mun, “Sahoejuŭi che kukka chohyŏng yesul chŏllamhoe,” 9.

- [42] Ibid., 10. The term Mun uses for “sense” is kamgak, which might also be translated as “feeling.”

- [43] Ibid., 15.

- [44] Jérôme Bazin, “The Reality of Class Struggle: Realism and Reality in East German Socialist Realism,” OwnReality 1 (2013), 4.

- [45] “Sahoejuŭi che kukka chohyŏng yesul chŏllamhoe simsa wiwŏndŭl, chŏllamhoe ch’amgwan chosŏn misulga kwan’gwangdan mossŭk’ŭbaro ch’ulbal” [Members of the reviewing committee of The Art of Socialist Countries and a tourist group that will visit the exhibition leave for Moscow], Chosŏn misul (April 1959), 26. The article indicates that the ink painter Lee Sŏk-ho accompanied Mun Hak-su as a delegate to the Moscow symposium. Lee’s role in the symposium seems to have been overshadowed by Mun’s, as North Korean sources give virtually no account of any remarks he might have delivered.

- [46] Tatiana Gabroussenko, Soldiers on the Cultural Front: Developments in the Early History of North Korean Literature and Literary Policy (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2010), 19.

- [47] Gabroussenko, Soldiers on the Cultural Front, 19–20.

- [48] Rossen Djagalov, From Internationalism to Postcolonialism: Literature and Cinema Between the Second and Third Worlds (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2020), 16.

- [49] Mun, “Sahoejuŭi che kukka chohyŏng yesul chŏllamhoe,” 10.

- [50] The Korean title reads, “Yŏngye e taehan kŭrŭttoen saenggak.”

- [51] Mun, “Sahoejuŭi che kukka chohyŏng yesul chŏllamhoe,” 13.

- [52] Feist, Principles and Methods, 28.

- [53] Ibid.

- [54] Ibid.

- [55] Peter H. Feist and Gabriele Sprigath, “Socialist Realism Is on the Move,” trans. Jonathan Blower, Art in Translation, vol. 5, no. 1 (2013), 111.

- [56] Feist and Sprigath, “Socialism Realism Is on the Move,” 111.