Walter Benjamin, Roland Barthes, Craig Owens: The Ends of Allegory in Postmodernism

Historian Perry Anderson reminds us that it was in the United States that postmodernism gained traction, “not as an idea, but as a phenomenon.”[1] In New York around 1980, artists, art critics, and intellectuals shaped the contours of a new critical approach: postmodernism uncovered circuits of power and oppression in society, and revealed how grand narratives shore up fictions of the status quo. Although postmodernism would later be criticized as a game played out in an ivory tower, the stakes for critical thought were real enough. Now is the time to investigate a phenomenon that drew on modernism as well as disavowed it.

Craig Owens’s celebrated essay, “The Allegorical Impulse: Toward a Theory of Postmodernism,” appeared in two installments in the New York journal October in 1980. October was the flagship for new approaches to visual art and literature inspired by French structuralist and post-structuralist theory. In his essay, Owens enlists French post-structuralist Roland Barthes, but he also draws on Walter Benjamin’s theory of allegory from the 1920s. In 1977, three years before Owen’s essay appeared in October, Charles Rosen introduced Benjamin’s theory of allegory to an American audience. Benjamin’s theory of allegory and its reception in the United States sets the stage for my exploration of Owens’s essay, the problem of form, and the critic’s task in relation to the work of art.

Part I

It is well-known that Walter Benjamin’s postdoctoral thesis on the German Baroque mourning play, The Origin of German Tragic Drama (Ursprung des deutschen Trauerspiels), was turned down by members of the faculty of the University of Frankfurt in 1925, first in the Department of Germanic Studies and then in Kunstwissenschaft (Science or Philosophy of Art). Benjamin wrote his postdoctoral thesis—the requirement for a university lectureship—between 1919 and 1925, although two essays from 1916 show his central ideas maturing earlier.[2] A collector of Baroque poetry and emblem books “for his personal delight,” he could now “ferret with intent” in his own library as well as “among the folios, broadsheets and in-octavos of the Berlin Staatsbibliothek.” Hard at work, he made “some six-hundred excerpts from long-dormant Baroque plays, from theological tracts of that tormented period, and from secondary sources.” This would be his only completed book apart from Einbahnstraße (One-Way Street), a collection of aphorisms published in 1928.[3]

Benjamin’s thesis topic was part of a renewed interest in the Baroque in Germany. When the Pergamon Altararrived in Berlin in 1880, it sparked interest in as well as controversy over the Baroque as a style of art.[4] Viewed first-hand, the extraordinary quality of the relief sculpture was undeniable, but the overt dynamism and “painterliness” of form contrasted with Winckelmann’s “noble simplicity and serene grandeur” of Greek classical sculpture. A new designation, “the Hellenistic Baroque,” was required to accommodate the surprising features of the Pergamon Altar. In Vienna, meanwhile, art historians August Schmarsow and Alois Riegl expanded understanding of the style through close study of Baroque architecture and Counter-Reformation contexts.[5]

At the end of the 1880s, German-speaking Swiss art historian Heinrich Wölfflin complicated this positive view of the Baroque, arguing that the “Baroque” was a style derived from a Renaissance, “Classical” ideal.[6] His book Principles of Art History (Kunstgeschictliche Grundbegriffe), published in 1915, continued the mission to rectify Scharsow and Riegl’s conceptual imprecision.[7] The Principles earned Wölfflin a wide following in his lifetime, and would go on to have a global reception, becoming a set text in art history for decades.[8] Benjamin attended Wölfflin’s lectures in Munich in 1915, the same year the Principles appeared. In a letter to his friend Gershom Scholem, he criticized the professor’s focus on characteristics of style that missed those essential sources in artworks “which are the most inaccessible.”[9] Benjamin would train his sights on those “inaccessible” sources that Wölfflin’s method failed to capture.

The belief in classicism as an ideal and the Renaissance as the pinnacle of artistic achievement was clearly shifting in these years. While Schmarsow and Riegl continued their careful studies, artists and writers associated with German Expressionism discovered in the Baroque a precursor to the anti-classical form they valued. Benjamin was drawn to the various facets of renewed interest in the Baroque in Germany, but he also valued the unfolding tradition of modern esoteric literature: “1921 is the date of Joyce’s Ulysses, 1922 of Eliot’s The Waste Land and Rilke’s Sonnets to Orpheus, while Yeats’s A Vision appeared in 1926,” Charles Rosen observed. Benjamin’s book “is a masterly work in that tradition.”[10]

Benjamin would continue to focus on periods of art deemed “in decline,” on objects deemed “imperfect and incomplete,”[11] and on art historians who studied such lowly material. His review essay of the Vienna School art historians, “Rigorous Study of Art: On the First Volume of the Kunstwissenschaftliche Forschungen,” appeared in 1933, the year Hitler rose to power in Germany. In this review Benjamin praises the “willingness” of the Viennese art historians “to push research forward to the point where even the ‘insignificant’—no, precisely the insignificant—becomes significant.” Riegl is “the precursor of this new type of scholar,” who “raises the inconspicuous material contents of an object (Sachgehalte) to the level of signification or meaning (Bedeutungsgehalte). It is Riegl’s method, grounded in “the philosophy of history,” which enables such “masterly command of the transition from the individual object to its cultural and intellectual [geistig] function.”[12] Akin to Riegl’s own rehabilitation of the late Roman art industry, Benjamin hoped to restore the vitality of the German Baroque and to reveal its historical and trans-historical qualities.

Hitler’s rise to power in Germany reminds us that Benjamin’s work “took place against a darkening domestic and political backdrop” of antisemitism.[13] Sorrowfulness may be the red thread through his book, from the German seventeenth century to the 1920s, and into the future. Indeed, Benjamin perceived in the Baroque plays a link between past and present; his essays and book on the Trauerspiel are studies of his own time as well. Allegory features centrally here, for Benjamin’s understanding of the German Baroque as a significant historical period, and of the mourning play as an exemplary form, is underpinned by his theory of allegory.

Perhaps the reader has already concluded that Benjamin’s approach to the German Baroque was idiosyncratic, that his ideas and discoveries were incomprehensible under academic standards of the day. The rejection of the postdoctoral thesis ruined any chance of the academic career that Benjamin (at least in some part of himself) was hoping to have. Yet he must have also realized (in some part of himself) what the outcome would be. “Benjamin’s text is multiple in its voices and intentions,” the literary critic George Steiner writes. The Origin of German Tragic Drama draws on two “radical, sharply idiosyncratic books, two exemplary precedents” for its “subversion” of the university “from within”: Hegel’s Phenomenology and Nietzsche’s The Birth of Tragedy. The Hegelian idea of history and the Nietzschean textual echoes do not blend easily in Benjamin’s text. On the one hand, the book presents a dizzying display of academic erudition; one the other hand, as Steiner says, it offers “a poetic-metaphysical meditation unique to Benjamin’s intellectual world and private feelings.”[14] German philosopher Theodor Adorno, one of Benjamin’s most important interlocutors, would praise his “philosophy of fragmentation” for breaking with “the theologically grounded philosophies of the past” and for countering myth and reification.[15] All the same, in his postdoctoral thesis, Benjamin set himself up for academic failure by relying on the fragment as a structuring principle and on the allegorical image as a conveyor of meaning.

“The Ruins of Walter Benjamin,” the title of Charles Rosen’s enduring essay published in The New York Review of Books in 1977, invokes the double resonance, the twinned fate, of Benjamin’s book and academic career. Rosen begins on a positive note, informing the reader that “after many years of announcement and postponement,” New Left Books has “finally issued a translation of Benjamin’s book in England.” Nevertheless, for “those who are interested in Benjamin and don’t read German, the situation is gloomy,” he continues, since the holders of the American rights are “sitting on them” and appear “to have no intention of making the British translation of this work available” in the United States.[16] The non-appearance of Benjamin’s book in the United States and dearth of translations of his writings into English make Rosen’s sensitive, probing essay a watershed.[17] Rosen not only provides a lucid account of symbol and allegory in Benjamin’s book, he also emphasizes—rather unusually for that time—the influence of early German Romantic aesthetics on Benjamin’s thought. When Rosen’s essay appeared in The New York Review of Books, allegory was gathering force as a “strategy” in contemporary (postmodern) art in the United States.

Part II

Benjamin described his approach as a new mode of “philosophical contemplation”: an “intentionless state of knowing” that recalls “in memory the primordial form of perception.”[18] Putting received ideas and concepts to one side, Benjamin excavates beneath the surface to discover the “most essential” yet “inaccessible” sources of works of art and historical periods, genres, or images. Adorno observed his penchant for “evidentness,” or “the specific gravity of the concrete in his philosophy,” which enabled him to “lead philosophy out of the ‘frozen wasteland of abstraction’ and carry thought over into concrete historical images.”[19] In his book, Benjamin isolates a concrete historical image of Baroque allegory in its Lutheran and Counter-Reformation ambience.

In contrast to classical tragedy, which is rooted in myth, sacrifice and the transcendent, the Baroque mourning play is rooted in history and in the sense of history as catastrophe. Where classical tragedy employs the symbol predominately, the Trauerspiel draws on allegory and allegorical modes of presentation. Where the symbol unites object and meaning in its form, in allegory object and meaning are conceived as clearly distinct entities. Meaning is hidden or delayed. Allegory is a “figure of false semblaunt,” Angus Fletcher writes, “a method of double meanings” or “a mix of making and reading combined in one mode, [whose] nature is to produce a ruminative self-reflexivity.”[20] For maker and interpreter, we might say, allegory is a problem of form.

In his book, Benjamin takes a tour through Melencolia I, Albrecht Dürer’s master engraving of 1514, embroidering on material laid out in Fritz Saxl and Erwin Panofsky’s erudite study, published a few years earlier, in 1923.[21] Born under the sign of Saturn and the polarity of Chronos, Melancolia is doomed to a pensive and feckless life. Dürer’s winged figure crouches on a low slab by an unfinished building, hand resting on her cheek, a brooding thinker or “unhappy genius.” As Panofsky says, “hers is the inertia of a being which renounces what it could reach because it cannot reach for what it longs.”[22] Melencolia holds an unused compass in her right hand; tools with which to make, measure, or describe the world lie scattered, untouched, by her feet.

Benjamin enters the stream of debate on Melencolia I, relaying the print’s intricate iconography and hidden meanings. In a stroke of original research, he discovers in Dürer’s engraving a concrete image of the Baroque in its German ambiance. Melencolia I expresses the earthbound heaviness of soul that Lutheranism would produce in great men when it deprived human actions of all value: “In that excessive reaction which ultimately denied good works as such, and not just their meritorious and penitential character,” he writes, “there was an element of German paganism and the grim belief in the subjection of man to fate. […] Something new arose: an empty world.”[23]

In the particular concreteness of the German Baroque—its awkwardness, lifelessness, and love of ruins—Benjamin perceives the symptoms of this empty, Lutheran world. Dürer’s engraving “anticipates the Baroque in many respects,” he writes, since in Melencolia’s proximity “the utensils of active life are lying around unused on the floor, as objects of contemplation.” Benjamin describes the theatrical and emblematic world of the Baroque in similar terms: replete with “pensiveness of gravity,” “self-absorption,” and in extreme states of mournfulness, “depersonalization.”[24] Here, contemplation and depersonalization are linked, each measured through the other term. As person and world separate, any natural concourse between person and things of the world disappears. Things of the world become objects of contemplation, but the meaning of things separates from the things themselves. Hence, the concreteness of things; hence, their seeming awkwardness. “[T]he most simple object appears to be a symbol of some enigmatic wisdom because it lacks any natural, creative relationship to us,” Benjamin observes.[25] Things are dumb (stumm; blöde) yet their silence, their awkwardness, is fringed with enigma.

In “The Centaur,” written in 1917 and published posthumously, Benjamin evokes the sorrowfulness emerging from the separation of word and life in vivid, chiming prose: “Where the word does not give life, life takes its time in coming awake, and where the creation takes its time and lingers, it is sorrowful.”[26] Here, we might say, the visual image of Melencolia is distilled in a linguistic image. Here, the language of communication is a voice over the void. Melencolia, the mournful witness to a creation that refuses to come awake with life, recalls the separation of object and meaning in Benjamin’s theory of allegory. If allegory acknowledges the state of separation, the melancholy allegorist sets her sights on a futile repair. At best, silent awkward things expose a trace of the metaphysical, living wor(l)d.

In Benjamin’s account of Baroque allegory, contemplation is at once an effect and a force. When he notes how life despises death and rises up against it, we might hear the echo of Freud. Yet Benjamin says that life rises up against the empty world and attempts to revive it through contemplation. To conjure meaning from the husks of objects thus becomes a human endeavor to recover what has been lost—to recover, that is, the meaning of the world. For melancholy men with their ear to the ground, this endeavor proceeds in spite of its ultimate failure, for once the world has been emptied, non-communicative aspects of word and world can no longer be expressed in human language. Allegory—the separation of object and meaning, the separation of person and world—thus becomes a persisting aspect of the world. Object and meaning may continue to be yoked together in the symbol, or motivated in the sign, but the duty of the allegorist is to break down symbol or sign to reveal what has been lost in language as communication, including everyday speech.

In “The Ruins of Walter Benjamin,” Rosen rightly notes that Benjamin’s book is a painstaking academic exercise in explication of the Trauerspiel—an exemplum, in other words, of language as communication. It is also a plea for the esoteric and for non-communicative aspects of language. “Language’s poetic and contemplative functions, and even the ways in which it can transform itself into a sacred text or become petrified as a magic formula” cannot be communicated directly, Rosen explains. Nevertheless, these non-communicative aspects of language exist as a feature of language as communication.[27] Benjamin has these non-communicative aspects, or capabilities, of language in mind when he says that words are not signs; words degenerate into signs, “into things that arbitrarily stand for something other than themselves.”[28] In order to recover non-communicative aspects of language buried within and obscured by language as communication, the allegorist burrows below the linguistic level of language to a non-linguistic register of meaning. Benjamin “attempts to grasp the phenomena before the dissimulation of language enters the picture.”[29]

Where academics might rely on the faculty of reason to sort things out, Benjamin’s melancholy allegorist draws on the full capacities of the mimetic faculty “to grasp the phenomenon.” This is an important point. “Benjamin’s is a mimetic and not a synthetic idea of reading,” as Anson Rabinbach has said.[30] The mimetic faculty includes sensuous similarity as well as non-sensuous similarity, and Benjamin’s allegorist relies on this entire toolkit. “Although Benjamin sees the world as a ‘script’” to be deciphered, “this script is not necessarily a text, and by no means is language the ontological pretext for interpretation.”[31] This distinction between “script” and “text” is worth bearing in mind as we go along. Benjamin’s mimetic reading, which interprets sensuous as well as non-sensuous similarity, transpires in a non-linguistic register of meaning. It thus includes interpretation of “what was never written.” “‘Read what was never written,’ runs a line in Hofmannsthal. The reader one should think of here is the true historian,” as Benjamin insists.[32]

Part III

In 1980, Craig Owens’s celebrated essay “The Allegorical Impulse: Toward a Theory of Postmodernism” appeared in October.[33] It begins with an epigraph from Benjamin’s 1940 essay “On the Concept of History”: “Every image of the past that is not recognized by the present as one of its own concerns threatens to disappear irretrievably.” Benjamin viewed history as a rescue operation—and Owens will train his sights on allegory’s “capacity to rescue from historical oblivion that which threatens to disappear.”[34] In a spirit of rehabilitation and recovery, Benjamin brought non-communicative aspects of language to light and demonstrated their loss as a modern condition. In the spirit of Benjamin, Owens will retrieve the allegorical impulse for the present and define it as a signal feature of postmodern art. He tells the reader that, at the time of his writing, “allegory has been condemned for nearly two centuries as aesthetic aberration, the antithesis of art.”[35] He names allegory’s prominent detractors: Croce, Borges, and Greenberg.

The name Clement Greenberg resonates especially here, since his influential definition of modernist painting effectively wiped allegory from the map. For Greenberg, modernist painting is “pure painting”: a self-critical operation in which the artist jettisons anything extraneous to painting as an artistic medium.[36] This purifying operation begins with Manet in the 1860s and reaches its apogee with postwar American Abstract Expressionism. Since what distinguishes painting as an artistic medium is its material support, artists involved in this purifying operation will acknowledge the flatness of the material support over attempts at illusionism or painting’s utility in the world. “Purity” is thus here understood as “an art freed from both resemblance to the world and function within it,” as Hal Foster has said.[37]

Greenberg shutters modernist painting from the world in order to vouchsafe the autonomy of art, but Owens finds that postmodern art has concourse with history and the artist’s surrounding world. In fact, Owens considers allegory to be the mode best suited for the retrieval of the past into the present of art. He celebrates how new artistic strategies—appropriation, site specificity, impermanence, accumulation, discursivity, and hybridization—raze Greenberg’s boundary between art and life. This litany of artistic strategies supports Owens’s claim about a common impulse to break down the strictures of modernist painting in the new forms of contemporary art.

Owens’s desire to retrieve allegory from the dustbin of modernist art history resonates with Benjamin’s understanding of history as the recovery of the forgotten. And yet, what follows in the 1980 essay is a description and deployment of allegory that veers away from Benjamin’s conception. Owens writes that “allegory occurs whenever one text is doubled by another; the Old Testament, for example, becomes allegorical when it is read as a prefiguration of the New.” This “provisional description,” as he calls it, “accounts for both allegory’s origin in commentary and exegesis, as well as its continued affinity with them.”[38] Already one can see that Owens casts allegory as a mode of reading. With this definition of allegory in view, it comes as little surprise to discover two things as Owens proceeds (the emphases are his own): Firstly, “[i]n allegorical structure […], one text is read through another, however fragmentary, intermittent, or chaotic their relationship may be.” Secondly, “when this relationship takes place within works of art, when it describes their structure […], [a]llegorical imagery is appropriated imagery.”[39]

Listen closely now as Owens characterizes the allegorist who “does not invent images but confiscates them”:

He does not restore an original meaning that may have been lost or obscured: allegory is not hermeneutics. Rather, he adds another meaning to the image. If he adds, how[ever, he does so only to replace: the allegorical meaning supplants an antecedent one; it is a supplement. This is why allegory is condemned, but it is also the source of its theoretical significance.[40]

Owens begins, in the spirit of Benjamin, with “allegorical interpretation,” noting how allegory functions in “the gap between past and present” so as to redeem the past for the present.[41] But several pages on, a shift occurs at the level of structure: the restoration of “an original meaning” is effaced by the theory of allegory as the replacement of one meaning by another. The swerve is decisive.

Repeated invocations throughout the essay’s two installments of “structure,” “supplement,” and the “deconstructive impulse” reveal the theoretical fashions of the day. Hermeneutics has become “reading.” The palimpsest is pronounced the allegorical form par excellence.[42] The move from hermeneutics to “reading” parallels another move in the essay: the shift from history to discourse. This shift, from the third person (“we” or “one”) to the first or second person (“I” or “you”), brings the work of art and the beholder into relation. The work of art is now directed, or addressed, to the beholder and she becomes its “reader.” This shift echoes “the death of the author and the birth of the reader” in Roland Barthes’s celebrated essay, “The Death of the Author” (English translation 1967; French 1968).[43] With shifts to “reading” and “discourse,” the question of meaning becomes a matter of deciphering, that is, a matter of legibility or illegibility. Just as “reading” is here understood horizontally—as art historian or beholder seek to “read” one text through another—so the work of art is brought onto the plane of the present and the present-day viewer.

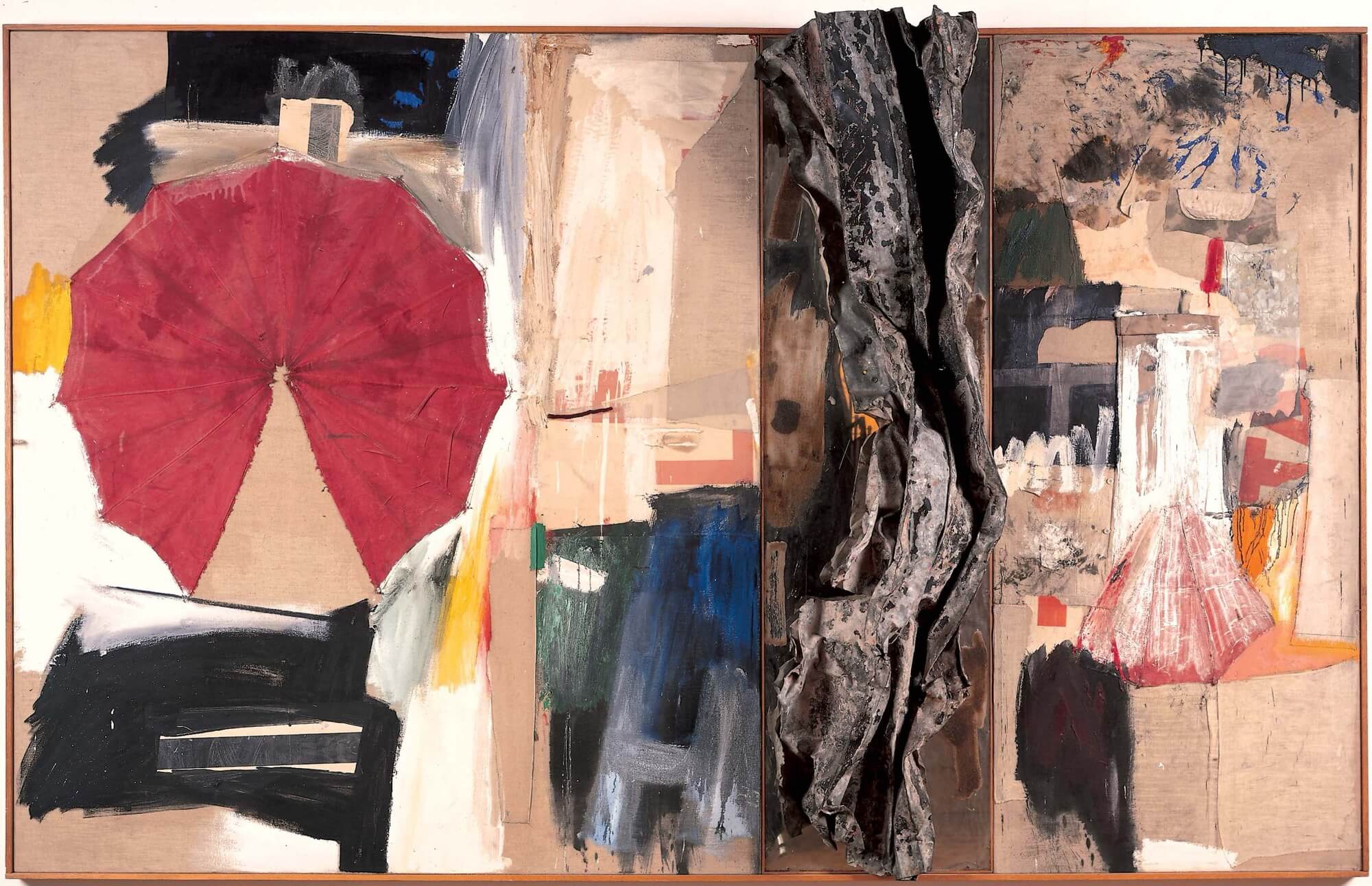

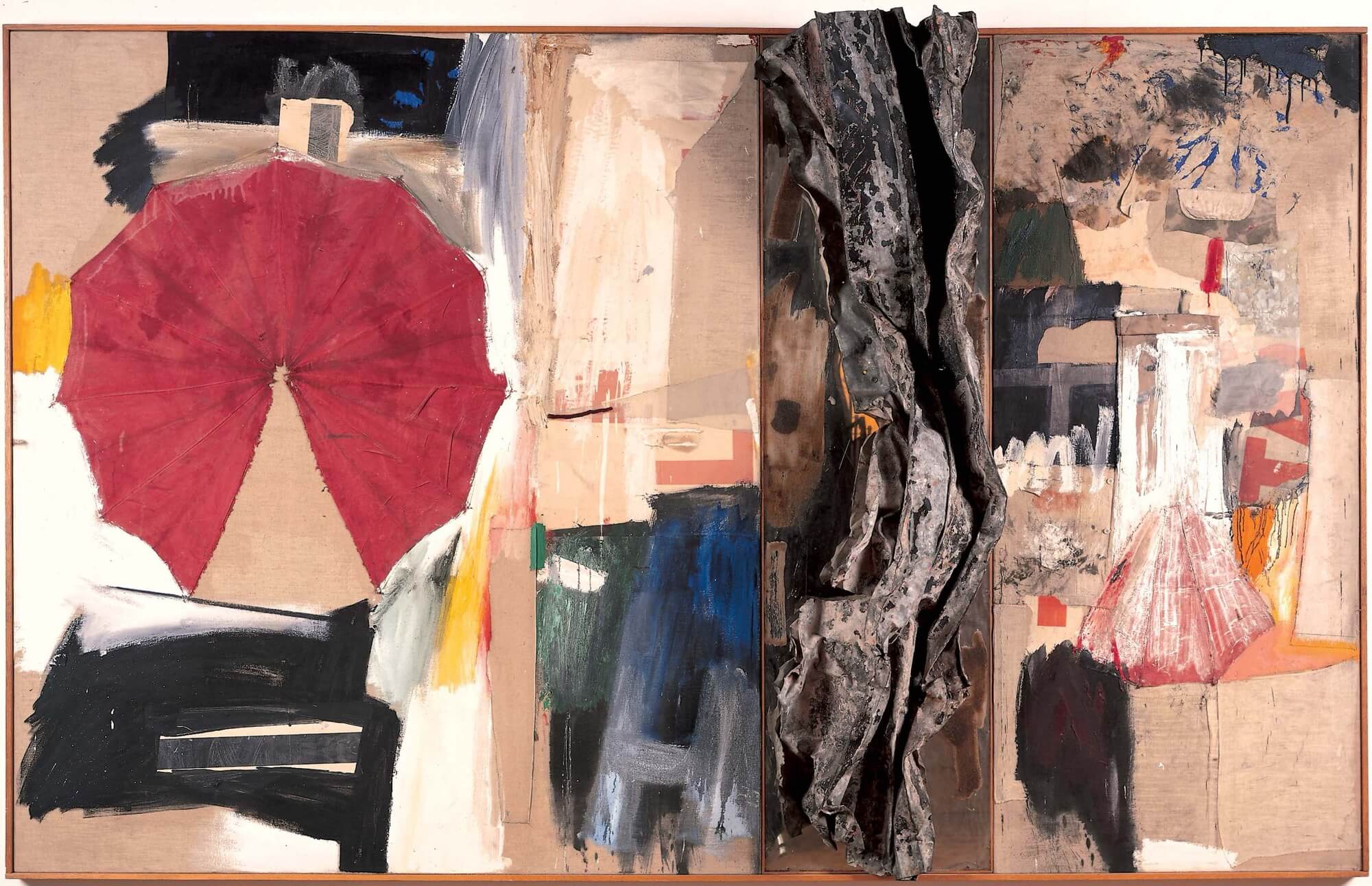

Having laid out his theory of allegory, Owens turns to the artistic strategies of the postmodern impulse. Robert Rauschenberg’s Allegory, a large combine painting from 1959–60, is heralded as postmodern avant la lettre. Surely a nightmare for Clement Greenberg, Rauschenberg’s Allegory would appear to include everything the artist could get his hands on in the world: a red umbrella, which Owens nicely describes as “stripped from its frame and splayed like a fan,” crumpled, rusted sheet metal, red block lettering from a broadside, swatches of fabric, mirrored panel, paint, metal, sand, glue. Allegory is “a random collection of heterogeneous objects,” Owens explains. Focusing on the means by which Rauschenberg’s combine painting denies “links of connection” between parts and materials, and how it appears a “dumping ground” or field of irredeemable fragments, Owens reads the painting as “the narrative—the allegory—of its own fundamental illegibility.” This is where, he intones, “everything finally comes to rest.”[44] Owens’s reading closes off connections within the artwork, as well as the artwork’s connections to history.

In the part two of “The Allegorical Impulse,” Owens leans on Paul de Man’s recently published book Allegories of Reading to read artworks by Rauschenberg and Cindy Sherman (among others) as “allegories of unreadability.” The aim here is to show how these artists “problematized the activity of reference” by setting up “that blind confrontation of antithetical meanings which characterizes the allegory of unreadability.”[45] Sherman’s Untitled Film Still no. 56, a small work from 1980 not mentioned by Owens, is one in an expanding series of photographic self-portraits in which the self does not appear as itself. Rather, the self appears as an image in the guise of a woman from the cinematic culture of the 1950s and 1960s. By drawing on cinematic culture, by transforming self into image, Owens says that Sherman’s work counters the self-critical tendency of modernism with a deconstructive impulse. Having spent several pages unpacking Barthes’s essay “The Third Meaning: Research Notes on Some Eisenstein Stills,” he is ready to claim that Sherman’s use of the film still format “parallels” Roland Barthes’s interest “in the theoretical value of the film still.”

Part IV

In “The Third Meaning,” Barthes focuses on the concreteness of the film still, since, as he says, the “filmic” can only be located in the still. For Barthes, “the filmic begins only where language and metalanguage end.” He writes:

The filmic, then, lies precisely here, in that region where articulated language is no longer more than approximative and where another language begins (whose science therefore cannot be linguistics, soon to be discarded like a booster rocket).

This other language is the third meaning. Barthes also calls it the obtuse meaning. Like Benjamin, he locates meaning in the fragment. As he says (in his emphasis), “the filmic can only be grasped in the still,” and the still “offers us the inside of the fragment.”[46]

Barthes proposes three levels of meaning in the film still. The first, “informational” level, is that of communication and its mode of analysis is the semiotic “message.” Using a still from Sergei Eisenstein’s film Ivan the Terrible as an example, he shows how the first level “gathers together everything” one “can learn from the setting, the costumes, the characters, their relations,” and “their insertion in an anecdote.” The second, “symbolic” level, is that of signification and its mode of analysis is a neo-semiotics of message and symbol (which expands in Barthes’s theory to include psychoanalysis, economy, and dramaturgy). In a still of Ivan’s face curtained by a shower of gold, the meaning of the gold is semiological because, he writes, “the gold brings in a (theatrical) playing, a scenography of exchange, locatable both psychologically and economically.”[47] The first and second levels comprise “the obvious meaning of the film still.”

“Is this all?” Barthes asks, rhetorically. “No,” he replies. For he is “still held by the image”: “I read, I receive (and probably even first and foremost) a third meaning evident, erratic, obstinate.” This third level corresponds to hearing in the classical paradigm of the five senses, and the reader is reminded that hearing was “first in importance in the Middle Ages.” For Barthes, this is “a happy coincidence,” since “what is in question here is indeed listening.” Listening, because the remarks by Eisenstein to which Barthes refers “are taken from a consideration of the coming of sound in film.” Listening, because it “bears within it that metaphor best suited to the ‘textual’: orchestration [which is Eisenstein’s own word], counterpoint, stereophony.”[48] Barthes is now ready to draw a distinction between linguistic and textual “listening.” If one takes away the obtuse meaning, “communication and signification still comes through,” he observes, because the third meaning is neither “in the language-system (even that of symbols),” nor is it “situated structurally.”[49] The third meaning emerges and begins to be grasped only in the filmic, which is to say, with Barthes, “inside the fragment” of the still rather than in the language-system of the film.

On the level of the third meaning, one receives the meaning even though “one does not know what the signified is.”[50] Indeed, Barthes continues, the obtuse meaning “does not copy anything”—the third meaning is a signifier without a signified.[51] “How do you describe something that does not represent anything?” he asks. He answers that “this third level—even if the reading of it is still hazardous—is that of signifiance, a word which has the advantage of referring to the field of the signifier (and not of signification) and of linking up with […] a semiotics of the text.”[52] In other words, on the third level, meaning is compacted in the field of the signifier rather than achieved through signification, as would occur in language as communication. This is enacted in the essay itself: Barthes tries to give words to “the supplement that his intellect cannot succeed in absorbing”; however, the obtuse meaning is, as he says, “at once persistent and fleeting, smooth and elusive.”[53]

Barthes unfolds the etymology of the word “obtuse” to find that it “already provides us with a theory of the supplementary meaning,” for (in his emphasis) obtusus means “that which is blunted, rounded in form.” The word “obtuse” also refers to an opening out, as in an obtuse angle, “greater than the pure, upright, secant, legal perpendicular,” he writes, with an eye on what is to come. Finally, in a pejorative connotation, the meaning of obtusus “extends outside culture, knowledge, information” to refer to that which is dull or stupid.[54] The obtuse meaning of the film still is all of these things. Blunted, the obtuse meaning does not appear directly. It is an artifice, a disguise.

In two Eisenstein stills of a grieving woman, illustrated one atop the other in the essay, Barthes discovers the fleeting traces of the obtuse meaning. In the uppermost image, “the closed eyelids, the taut mouth, the hand clasped on the breast” belong to “the full signification” of the still, which is to say, to the obvious meaning of the image as an expression of grief. These features are not only recognizable, they are part of “Eisensteinian realism and decorativism,” as Barthes says. Nevertheless, this image is an artifice of grief, a disguise. For here, a grief is suggested that does not appear directly. As he says, this image shows grief “just short of the cutting edge of grief.” Moving closer, Barthes locates the obtuse meaning in “the region of the forehead,” or even more precisely, in the “tenuous relationship […] of the low headscarf, the closed eyes and the convex mouth,” which lends to the image something of the comic, the low, the image d’Épinal. This woman’s “pitiful disguise” creates “a facetious, simpleton look,” he observes, a near comic stylization of grief whose emphatic emphasis hides an ellipsis of fleeting, elusive, inarticulate meaning. This is precisely what he means by “the third meaning.” In the lower still, by contrast, “the obtuse meaning vanishes,” he writes, “leaving only a message of grief,” which is also to say, a grief which appears directly.[55]

For Barthes, the obtuse image is what in the image is purely image. The “obtuse meaning is outside (articulated) language while nevertheless within interlocution,” he writes. It exists “over the shoulder” or “on the back” of articulated language. It is discontinuous with the time and narrative of the film. Concrete but unnameable, the obtuse meaning escapes language. And yet, as he makes clear, the obtuse meaning is sensed by the listener of the film.[56]

In “The Allegorical Impulse,” Owens describes the obtuse meaning as a supplement which disrupts narrative and “reading.” However, he fails to note the deeper registers of the obtuse meaning. For Barthes, the obtuse meaning is a supplement (indeed, narrative and meaning can proceed without it), but it is not supplementary. Rather, and more crucially, the obtuse meaning is “meaning on the cutting edge of meaning.” Indefinable and inexpressive, the obtuse meaning may be found in the play, the work of art, the filmic, the comic, or the low. Benjamin’s theory of the inexpressive or non-communicative aspects of language reveals something similar. Benjamin, too, noticed how the inexpressive lurks in disguise, how it often hides in the awkward or low image.[57] Cindy Sherman’s Untitled Film Still no. 56 deploys artifice to lay bare the artifice of cinematic images of women. This image does employ a deconstructive impulse to create an allegory of unreadability, as Owens says. But something in Sherman’s image escapes this “reading” of it, and this is Sherman’s art: to set up an artifice of longing which reveals an expression of longing that does not appear directly.

What Owens calls “the allegorical impulse” of postmodernism arose out of the particular political, social, and cultural contexts of late 1970s America. It also arose in response to the strictures of modernism.[58] Like Greenberg in his genealogy of modernist painting, Owens locates the roots of the allegorical impulse in Manet’s art of the 1860s. In a move at odds with Greenberg’s notion of “purity,” however, Owens sets Manet’s art in relation to the museum, since it was there, in his viewing of older art, that Manet discovered the elements he would forge into a new, modern art. Owens draws a genealogical line from Manet in 1860 to Rauschenberg and fellow artists in 1980. And while one surmises ruptures along the way—the very label “postmodernism” giving a hint of the greatest of these—one also surmises that this gathering of the dispirited and the disparate comes together under the sun of “the allegorical impulse.”

Owens’s emphasis on “reading” and “unreadability” distinguishes his account of postmodernism from Greenberg’s “Modernist Painting.” Nevertheless, the allegorical impulse of postmodernism dovetails with the impulse of modernist painting in a crucial sense: in both, the artwork’s meaning is coincident with the present. Meaning is legible or else illegible. Either way, meaning is gauged against the plane of the present and the beholder’s grasp in the present moment. Of course, Greenberg and Owens engaged with works of art coincident with their time—for them, these works of art were contemporary. Yet to consider the art of one’s time is not the same thing as to construe meaning as coincident with one’s time. By pulling the artwork into the present, Greenberg and Owens do not make way for the untimely work of art or the discontinuous in the work of art, except in those cases where the artwork is ahead of its time (avant-garde) or when the artwork mounts a critique of its time, through a deconstructive impulse, for example.

The works of art Owens considers in his essay may present a new form of allegory. The “allegorical impulse” he discovers in these works may be a means through which to unmask circuits of power and oppression in society. Perhaps these works are best read as “allegories of unreadability” that “problematized the activity of reference.” For all the referencing of Benjamin, it was not the author’s aim to reproduce Benjamin’s theory of allegory. Still, something of Benjamin’s understanding of allegory as a problem of form has fallen away in this account. When Owens swerves from the restoration of “an original meaning” to the replacement of one meaning by another, he sets allegory on the horizontal plane of the present. When he replaces hermeneutics with “reading,” and history with “discourse,” he invites theory to do the work of interpretation. It might even be said that theory comes to replace history.

For the art historian, the problem of form includes the problem of its possible meanings. Benjamin’s conception of allegory as a problem of form invites us to consider works of art, even those of our own time, as untimely. It invites us to consider meaning that is discontinuous with the time of the work of art as well as meaning that is inexpressive, yet present, in the work of art. Contemplation in Benjamin’s sense is taxing; it takes time. Where what Owens calls “reading” draws the work of art onto the plane of the present, and theory subsumes the work of art into a concept, contemplation in Benjamin’s sense—attentive, intentionless—regards the work of art in the manifold senses of its concreteness.

In The Origin of German Tragic Drama, Benjamin writes: “At one stroke the profound vision of allegory transforms things and works into stirring writing.”[59] For Owens, who quotes this sentence in his essay, allegory transforms the work of art into a (linguistic) script to be deciphered. For Benjamin, however, writing is stirring when contemplation stirs the image and the emotions. In contemplation, what lies on the periphery may unsettle the center; the awkward image may be fringed with enigma, as Barthes shows in his essay “The Third Meaning.” The art historian could make way for the untimely and the inexpressive in the work of art. These, too, are aspects of the problem of form.

- An earlier version of this essay, “Walter Benjamin’s Theory of Allegory as a Problem of Form,” appeared in English in: Hans Aurenhammer and Regine Prange, eds., Das Problem der Form: Interferenzen zwischen moderner Kunst und Kunstwissenschaft (Berlin: Gebr. Mann, 2016), 43–57.

- [1] Perry Anderson, The Origins of Postmodernity (London and New York: Verso, 2006), vii.

- [2] Walter Benjamin, “Trauerspiel and Tragedy” and “The Role of Language in Trauerspiel and Tragedy,” trans. Rodney Livingstone, in Selected Writings, vol. 1, ed. Marcus Bullock and Michael W. Jennings (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 2011), 241–50. Both essays were published posthumously.

- [3] George Steiner, “Introduction” to Walter Benjamin, The Origin of German Tragic Drama, trans. John Osborne (London: Verso, 1977), 9–11. Steiner provides a rich context for the book. The English-speaking protagonists of the present essay—George Steiner, Charles Rosen and Craig Owens—refer to the Osborne translation; for the purposes of historical accuracy, I do too. However, it is worth noting a new translation by Howard Eiland, Origin of the German Trauerspiel (Cambridge, MA and London: Harvard University Press, 2019).

- [4] My understanding of this affair relies on Alina Payne, “Portable Ruins: The Pergamon Altar, Heinrich Wölfflin, and German Art History at the fin de siècle,” Res: Anthropology and Aesthetics 53/54 (spring-autumn 2008), 168–89; and her “Rudolf Wittkower,” in Klassiker der Kunstgeschichte, vol. 2, ed. Ulrich Pfisterer (Munich: C. H. Beck, 2008), 107–23.

- [5] August Schmarsow, Barock und Rokoko: Eine Auseinandersetzung über das Malerische in der Architektur (Leipzig: S. Hirzel, 1897); and Der Barock als Kunst der Gegenreformation (Berlin: Paul Cassirer, 1921); Alois Riegl, Die Entstehung der Barockkunst in Rom (Vienna: Anton Schroll & Co., 1908).

- [6] Heinrich Wölfflin, Renaissance und Barock: Eine Auseinandersetzung über Wesen und Entstehung des Barockstils in Italien (Munich: Theodor Ackermann, 1888).

- [7] The full title is Heinrich Wölfflin, Kunstgeschichtliche Grundbegriffe: Das Problem der Stilentwicklung in der neueren Kunst (Munich: F. Bruckmann, 1915); Principles of Art History: The Problem of the Development of Style in Early Modern Art, trans. Jonathan Blower (Los Angeles: Getty Publications, 2015). See: Gabriele Wimböck, “Heinrich Wölfflin,” in Klassiker der Kunstgeschichte, vol. 1, ed. Ulrich Pfisterer (Munich: C. H. Beck, 2008), 131; and more generally, Evonne Levy’s chapter on Wölfflin in her book, Baroque and the Political Language of Formalism (1845-1945): Burckhardt, Wölfflin, Burlitt, Brinckmann, Sedlmayr (Basel: Schwabe, 2015).

- [8] Evonne Levy and Tristan Weddigen, eds., The Global Reception of Heinrich Wölfflin’s ‘Principles of Art History’ (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2020).

- [9] Gershom Scholem, “Walter Benjamin und Felix Noeggerath,” in Walter Benjamin und sein Engel: Vierzehn Aufsätze under kleine Beiträge (Frankfurt: Suhrkamp, 1983), 84–85; quoted in Thomas Levin, “Walter Benjamin and the Theory of Art History,” October 47 (winter 1988), 79–80.

- [10] Charles Rosen, “The Ruins of Walter Benjamin,” in Romantic Poets, Critics, and Other Madmen (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1998), 57; originally appearing across two issues of The New York Review of Books: “The Ruins of Walter Benjamin” (October 27, 1977), “The Origins of Walter Benjamin” (November 10, 1977). Rosen’s dates are slightly inaccurate: Ulysses was first serialized in The Little Review from 1918 to 1920 and then published as a book in 1922, while Yeats’s A Vision was published in 1925.

- [11] Benjamin, Origin, 45.

- [12] Walter Benjamin, “Rigorous Study of Art: On the First Volume of the Kunstwissenschaftliche Forschungen,” trans. Thomas Y. Levin, October 47 (winter 1988), 87–89. On Benjamin’s absorption and transformation of Riegl’s method, see: Karen Lang, Chaos and Cosmos: On the Image in Aesthetics and Art History (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2006), 147–57; and Giles Peaker, “Works that Have Lasted… Walter Benjamin Reading Alois Riegl,” in Framing Formalism: Riegl’s Work, ed. Richard Woodfield (Amsterdam: G+B Arts International, 2001), 291–309.

- [13] Steiner, “Introduction” to Benjamin, Origin, 10.

- [14] Steiner, “Introduction,” 12, 13.

- [15] Benjamin “remained uncorrupted by all […] attempts […] to grasp transcendence through natural reason, as though the limiting process of the enlightenment could be revoked and one could simply reinstate the theologically grounded philosophies of the past. For this reason from its inception his thought protected itself from the ‘success’ of unbroken cohesion by making the fragmentary its guiding principle.” Theodor Adorno, “A Portrait of Walter Benjamin,” in Prisms, trans. Samuel and Shierry Weber (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1986), 239. This fragmentation has its own history in Benjamin’s thought and writing, culminating in the aphoristic and montage structure of his last works.

- [16] Rosen, “The Ruins of Walter Benjamin,” 133.

- [17] Canvasing English translations available in the United States, Rosen notes that the “small selection” of Benjamin’s writings in Illuminations: Walter Benjamin. Essays and Reflections, edited by Hannah Arendt (New York: Schocken Books, 1969), contains only one of Benjamin’s major achievements, the now-canonical essay “The Work of Art in the Age of its Technical Reproducibility.” The omission of his important essay on Goethe’s Elective Affinities reflects the general neglect of that time in his early writings inspired by German Romantic criticism. This neglect helped set the stage for the popularity of his so-called Marxist or materialist writings (including the “The Work of Art” essay). A subsequent volume, Reflections: Walter Benjamin, Essays, Aphorisms, and Autobiographical Writings, ed. Peter Demetz (New York: Shocken Books, 1977), further promoted his middle and late writings at the expense of his early work. Reflections does contain two significant early essays, “On Language as Such and the Language of Man” (1916) and “Fate and Character” (1919). Stranded from the context of Benjamin’s early writing and its shaping concerns, however, these two essays cannot but have an esoteric flavor. After Rosen’s essay in 1977, the situation improved somewhat in spring 1979, when New German Critique published a special issue on Benjamin. The introductory essay, “Critique and Commentary/Alchemy and Chemistry: Some Remarks on Walter Benjamin and this Special Issue” (3–14), written by issue editor Anson Rabinbach, is an incisive and thought-provoking overview of Benjamin’s approach. For more on this context, see: Vera Schwarz, “The Domestication of Walter Benjamin: Admirers Flee from History into Melancholia,” Bennington Review 4 (April 1979), 7–11; and Jeffrey Grossman, “The Reception of Walter Benjamin in the Anglo-American Literary Institution,” The German Quarterly, vol. 65, no. 3–4 (summer–autumn 1992), 414–28.

- [18] Benjamin, Origin, 36–37.

- [19] Theodor Adorno, “Introduction to Benjamin’s Schriften,” in On Walter Benjamin: Critical Essays and Recollections, ed. Gary Smith (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1988), 3, 7. Benjamin’s Schriften (Writings) was published by Suhrkamp in two volumes in 1955. This and the proceeding quote show that Adorno thought of Benjamin’s writings as a philosophy—he relates his own philosophy to Benjamin’s. Adorno carries over the phrase “frozen wasteland of abstraction” from his Negative Dialectics, trans. E. B. Ashton (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1973), xix.

- [20] Angus Fletcher, “Allegory without Ideas,” in Thinking Allegory Otherwise, ed. Brenda Machosky (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2010), 10. See also Anselm Haverkamp and Bettine Menken’s entry on allegory in Ästhetische Grundbegriffe, vol. 1, ed. Karlheinz Barck et al. (Stuttgart: J. B Metzler, 2010), 49–104; Angus Fletcher’s classic study, Allegory: The Theory of a Symbolic Mode (1964) (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2011); and Brenda Machosky’s fresh considerations of art and allegory in Structures of Appearing: Allegory & the Work of Literature (New York: Fordham University Press, 2013). For Benjamin’s theory of allegory, one could begin with Burkhart Lindner, “Allegory,” in Benjamins Begriffe, vol. 1, ed. Michael Optiz and Erdmut Wizisla (Frankfurt: Suhrkamp, 2000), 50–94.

- [21] Fritz Saxl and Erwin Panofsky, Dürer’s Melencolia I. Eine quellen- und typengeschichtliche Untersuchung (Leipzig: B. G. Teubner, 1923). Benjamin also cites Karl Giehlow, “Dürers Stich Melencolia I und der maximilianische Humanistenkreis,” Mitteilungen der Gesellschaft für vervielfältigende Kunst, vol. 26, no. 2 (1903); and Aby Warburg, Heidnisch-antike Weissagung in Wort und Bild zu Luthers Zeiten (Heidelberg: C. Winter, 1920). Space does not allow me to explore this rich scholarly context.

- [22] Erwin Panofsky, Albrecht Dürer (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1945), 170.

- [23] Benjamin, Origin, 138–39.

- [24] Ibid., 140.

- [25] Ibid.

- [26] “Wo nicht das Wort belebt, wird Leben mit Weile wach und wo sich die Schöpfung verweilt ist sie traurig.” Walter Benjamin, “The Centaur,” trans. Howard Eiland, in Early Writings 1910-1917 (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 2011), 283. As Eiland points out, the passage “is notable for its paronomasia or chiming verbal permutations (on the model of Hölderlin and archaic texts).”

- [27] Rosen, “The Ruins of Walter Benjamin,” 164.

- [28] Ibid., 159.

- [29] Rabinbach, “Critique and Commentary/Achemy and Chemistry,” 9.

- [30] Ibid.

- [31] Ibid.

- [32] Walter Benjamin, “Paralipomena to ‘On the Concept of History’” (1940), in Selected Writings, vol. 4, ed. Howard Eiland and Michael Jennings (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 2003), 405. The quotation is from Hofmannsthal’s 1894 play Death and the Fool (Der Tor und der Tod). See also Benjamin, “On the Mimetic Faculty” (1930), in Selected Writings, vol. 2, ed. Michael Jennings, Howard Eiland, and Gary Smith (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 1999), 722, where Benjamin quotes the line “To read what was never written.”

- [33] Craig Owens, “The Allegorical Impulse: Toward a Theory of Postmodernism,” October 12 (spring 1980), 67–86; “The Allegorical Impulse: Toward a Theory of Postmodernism, Part 2,” October 13 (summer 1980), 58–80. These are reprinted together in: Craig Owens, Beyond Recognition: Representation, Power, and Culture, ed. Scott Bryson, Barbara Kruger, et. al. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992), 52–82. I will quote from this reprint. A year earlier, in “Earthwords,” October 10 (autumn 1979), 120–130, Owens discovered the allegorical impulse in the work of Robert Smithson.

- [34] Owens, “The Allegorical Impulse,” 52–53.

- [35] Ibid., 52.

- [36] Clement Greenberg, “Modernist Painting,” in Greenberg, The Collected Essays and Criticism, vol. 4, ed. John O’Brian (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995), 185–194. Greenberg’s essay was originally broadcast over radio on the program Voice of America in 1960. After a bit of retouching, it was published in Art and Literature (spring 1965). For the essay and its surrounding contexts, see: Francis Frascina, “Institutions, Culture, and America’s ‘Cold War’ Years: The Making of Greenberg’s ‘Modernist Painting,’” Oxford Art Journal, vol. 26, no. 1 (2003), 69–97.

- [37] Hal Foster, “At MoMA,” London Review of Books (February 7, 2013), 14.

- [38] Owens, “The Allegorical Impulse,” 53.

- [39] Ibid., 53–54.

- [40] Ibid., 54.

- [41] Ibid., 53.

- [42] Ibid., 54.

- [43] Roland Barthes, “The Death of the Author,” trans. Richard Howard, Aspen 5–6 (fall–winter 1967); first published in French in Mantéia 5 (1968).

- [44] Owens, “The Allegorical Impulse”, part II, 76–78.

- [45] Ibid., 79. Paul de Man, Allegories of Reading: Figural Language in Rousseau, Nietzsche, Rilke, and Proust (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1979).

- [46] Roland Barthes, “The Third Meaning: Research Notes on Some Eisenstein Stills,” in Barthes, Image, Music, Text, ed. and trans. Stephen Heath (London: Fontana, 1977), 62, 64, 67. Emphasis in the original. The essay originally appeared in Cahiers du cinéma 222 (1970).

- [47] Ibid., 52.

- [48] Ibid., 53.

- [49] Ibid., 53, 60.

- [50] Ibid., 53.

- [51] Ibid., 60.

- [52] Ibid., 54. The word “signifiance,” which appears in italics in Barthes’s essay, is taken from Julia Kristeva’s theory of poetic language.

- [53] Ibid.

- [54] Ibid., 55.

- [55] Ibid., 56–65.

- [56] Ibid., 61. My emphasis.

- [57] A longer essay would take in Benjamin’s theory of the expressionless (das Ausdruckslose).

- [58] Owens’s construal of modernism as an object with discrete borders and specific features allows him to conceive postmodernism in opposition to it. After Owens’s essay appeared, scholars would open out this characterization of modernism by revealing inconsistencies, exclusions, and so forth in the received definition of modernism.

- [59] Benjamin, The Origin of German Tragic Drama, 176; quoted in Owens, “The Allegorical Impulse,” 64.