Archive: Art, Activism, and the Street in 1960s/70s Black Chicago

The photographs in this portfolio are news photos, mostly from the late 1960s, representing Black activism and art in Chicago during the Black Freedom Movement and Black Arts Movement. Many were never published in their respective newspapers (and in a few cases it’s not possible to determine with certainty what paper they were taken for), but for decades they were kept in photo archives, until they were sold in recent years, often through companies like Historic Images that do business through Ebay. I bought them for research purposes, primarily for my book Art for People’s Sake. A small number have appeared there and in exhibitions and exhibition catalogues to which I contributed. Eventually, I plan to donate them to a library, but in the meantime, I’m excited to have been offered the opportunity to share a selection of them online. Many of these images were never published at the time they were taken, and I hope they may offer new avenues for research and teaching—and potentially political inspiration.

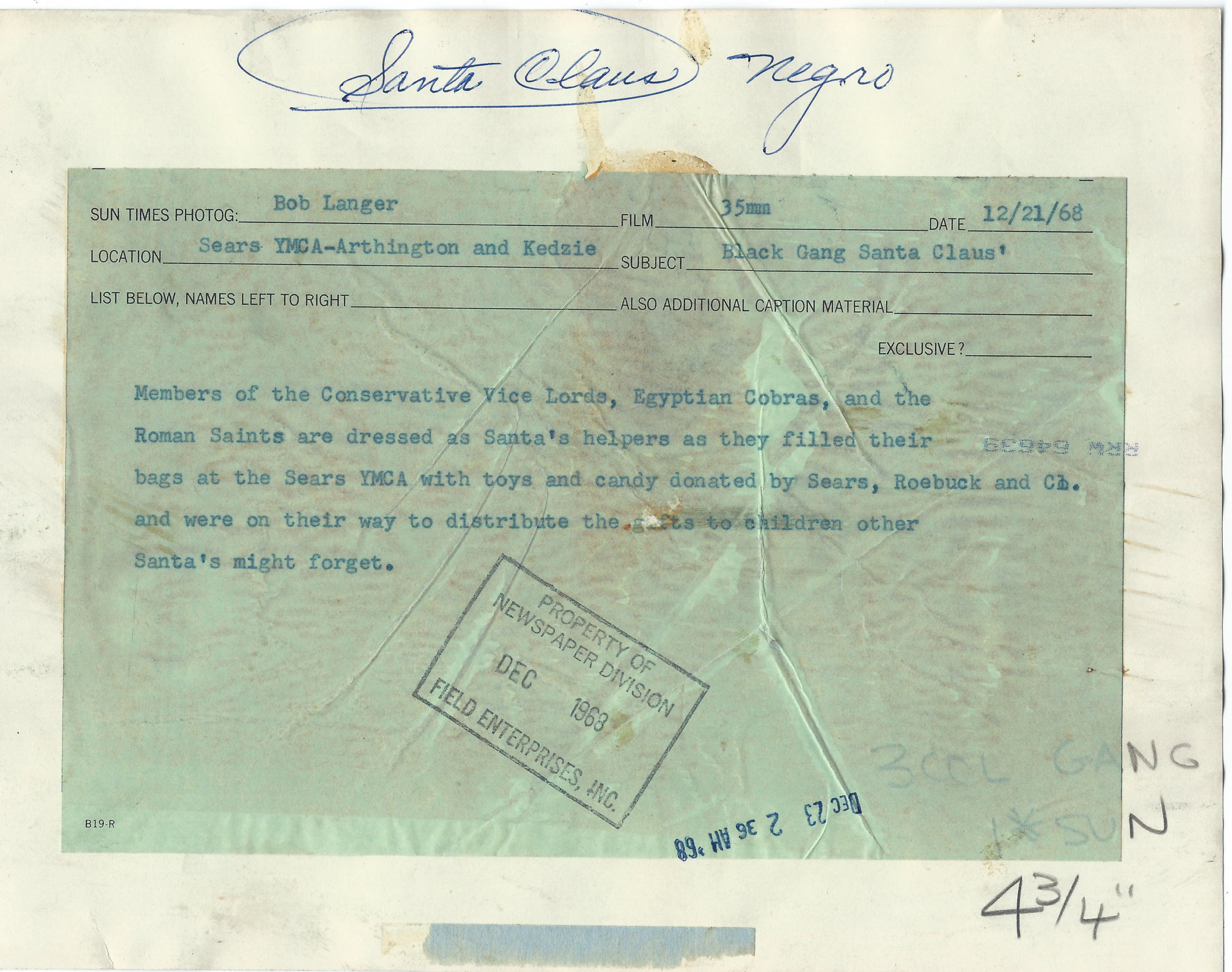

I’ve divided them into thematic sections (though there is a lot of overlap between the themes) and provide a brief introduction to each section that contextualizes the individual photos and points out some key features and notable background information. I’m including the backs of the photographs because they often contain material that is especially useful to researchers. They can include handwritten notes that reflect the newspaper’s filing system, typed stickers with information about the photographer and subject matter, stamps with dates (typically the day they arrived in the archive, which is often the day they were taken or not long after; they were usually printed in an in-house darkroom), and, importantly, the pasted clippings of newspaper articles in which the photos appeared.

In my research, these pasted articles often provided precious information, because several important papers are largely inaccessible (the Sun-Times is microfilmed, but somewhat haphazardly; the Daily News is not). It was standard practice when an article used a photo for the article clipping to be glued to the back, which means that most of the prints without an article on the back were unpublished; however, the absence of an article does not offer 100% certainty that the photo never appeared in the paper.

Titles were tricky, because the captions given to photos in the paper were often quite different from the photographers’ descriptions at the time of filing. I have generally tried to use the caption if it makes sense, and a descriptive statement (often drawing on the information provided by the photographer) in cases where there is no caption or the caption doesn’t do the photograph justice. Dates are also tricky; I’ve listed the date the photo was taken if it’s possible to discern, and also generally included the date of the stamp and/or date of publication.

These photographs do not provide a neutral view of events: the decisions to snap particular scenes were shaped by the agendas of large white-owned media corporations, even if photographers had some leeway to follow a story that interested them; most (though not all) of the photographers are/were white, and all were men; some topics (notably anything relating to the Black Panthers) were thinly represented by the time I started purchasing; and, finally, I personally made choices about what to buy as I pursued my research process.

Some of the photos have been interestingly cropped, like the photo of Conservative Vice Lords leader Bobby Gore (2.5) in which the context of the African Lion shop was removed when this image was used in conjunction with a story on his arrest. Others have been retouched, like A youth writes Black Power in shaving cream at intersection of Homan and Madison (3.3), which was modified by a photo editor who enhanced the white of the words for legibility. The latter photo in particular is, I believe, the result of a complex performance. I would argue that the young man writing “Black Power” was quite conscious of the presence of the photographer and intentionally producing an image for a broader audience through the use of the photographer’s camera and potential publication.

A key point in viewing these images that emerges from this particular case, but can be applied more generally, is that we need to understand the historical actors appearing in the camera’s lens not as passive objects but as, in fact, actors. Whatever the agenda of the photographer or his employer, these images also result from dialogue. An interpretation based on both political context and close visual analysis needs to take account of the fact that many of the subjects depicted in these images were aware of the power of the camera and deployed it for their own purposes.

The texts that accompany these images draw largely on my book, Art for People’s Sake: Artists and Community in Black Chicago 1965–1975 (Duke University Press, 2019), in which activists and street organizations figure as a primary locus of “community.” I refer readers to the book and its bibliography for further information. I also wish to cite here a few additional items of bibliography that help contextualize some of the specific events documented in the photographs. On the Chicago jobs campaign see most recently Toussaint Losier, “The Rise and Fall of the 1969 Chicago Jobs Campaign: Street Gangs, Coalition Politics, and the Origins of Mass Incarceration,” The University of Memphis Law Review, Vol. 49, No. 1 (2018), 101-136 (watch for his forthcoming book on the rise of mass incarceration as a response to the politicization of gangs). On the West Side Paper Stock Corporation, see “Black Business Cures Pollution Problem,” Congressional Record, Volume 116, Part 14, June 4, 1970. On the uprising that marked the one-year anniversary of the murder of Martin Luther King, Jr., see “City Quiet Under Guard,” Chicago Tribune, April 4, 1969. On the convent occupations, see among other articles (in chronological order) “Neighborhood Group Seizes Old Convent,” Chicago Tribune, July 14, 1969; “Convent Still Held by Gangs on West Side,” Chicago Tribune, September 23, 1969; “Wreckers Move In on Convent,” Chicago Tribune, November 9, 1969; and “Community Raps Church: Want Convent For Center,” Chicago Daily Defender, December 2, 1969.

– Rebecca Zorach

sections:

one • murals and culture

two • gangs, art, mark-making

three • uprising

four • street organizations & community organizing

five • Black power and direct action

six • Black power and the police