3. Uprising

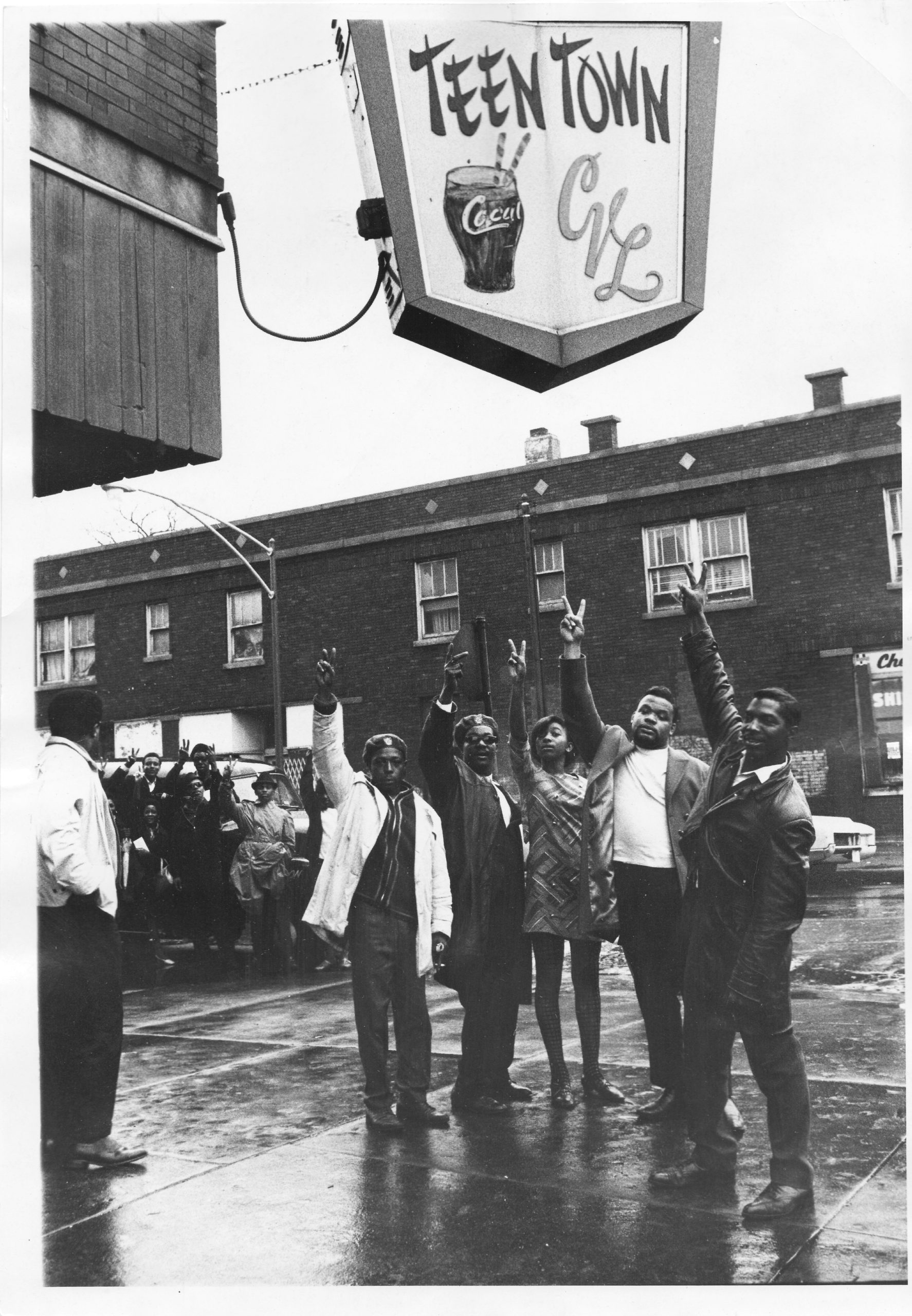

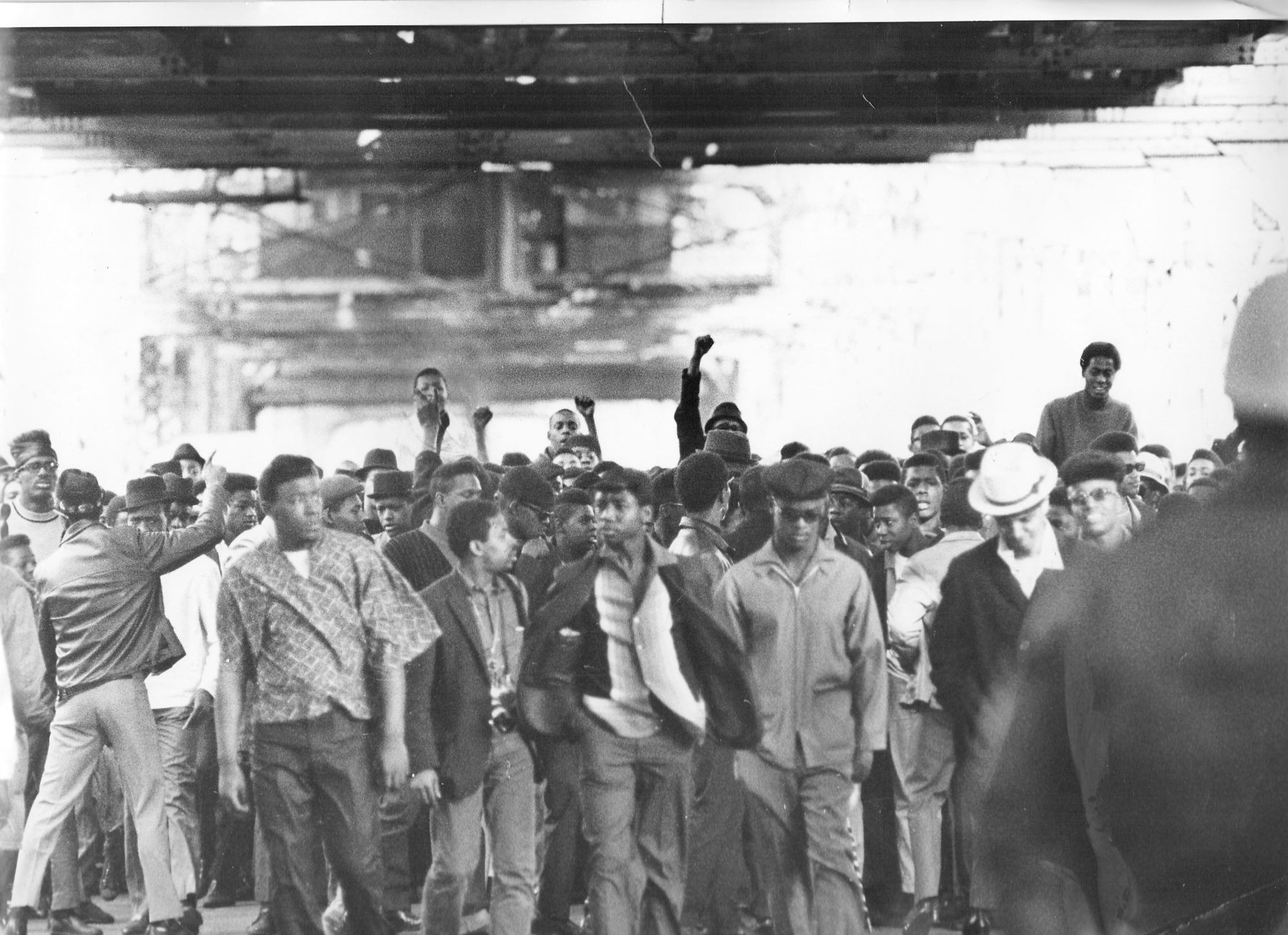

Among the CVL’s other business ventures was a teen center called Teen Town. Unbeknownst to the members and friends who (along with members of the press) came to celebrate its opening on April 4, 1968 (3.1), it was a fateful day: the day Martin Luther King was assassinated in Memphis, Tennessee. Around the country, this event sparked uprisings in Black communities that were under enormous stress—economic and otherwise—and were, at the same time, developing a more radical political consciousness. On the South Side, the Blackstone Rangers joined together with another gang, the Disciples, to keep the peace and prevent damage to Black businesses and homes (3.2). On the even poorer West Side, although the CVL tried to intervene in a similar way, the destruction was massive. Some West Side neighborhoods have never fully recovered from the aftermath, in particular the departure of larger businesses (notably Sears, Roebuck and Company, the neighborhood’s major employer) and an apathetic response from the city.

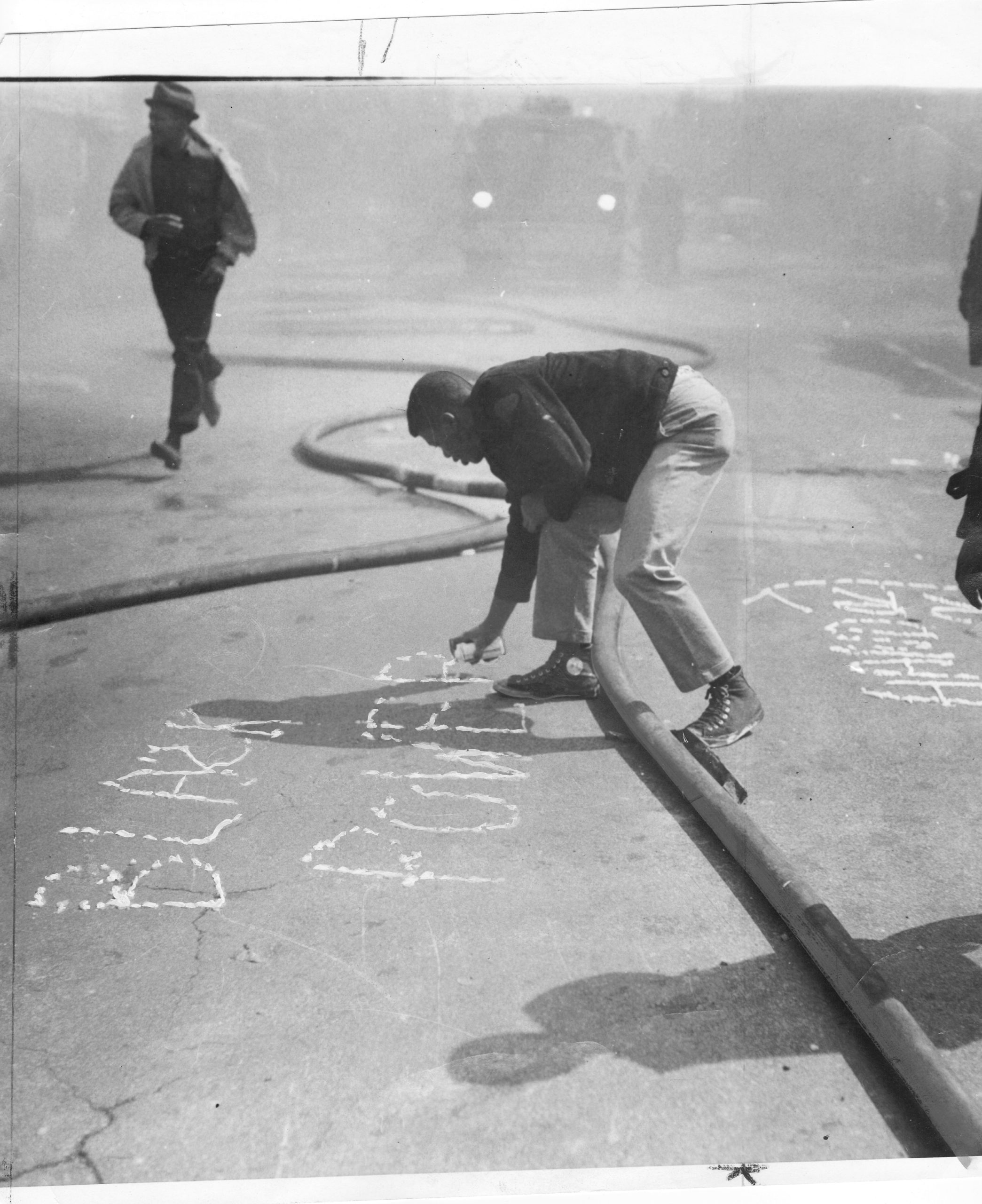

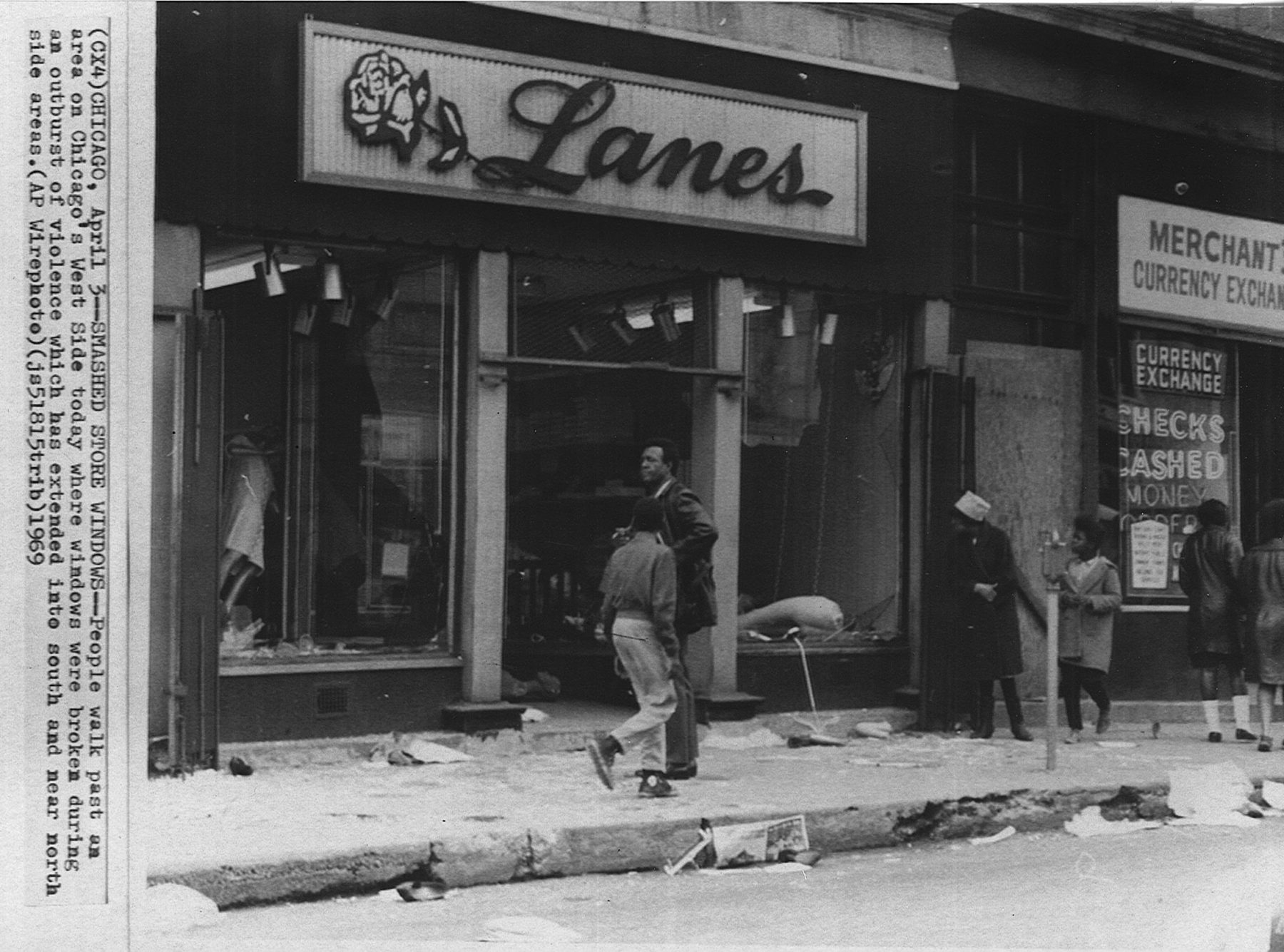

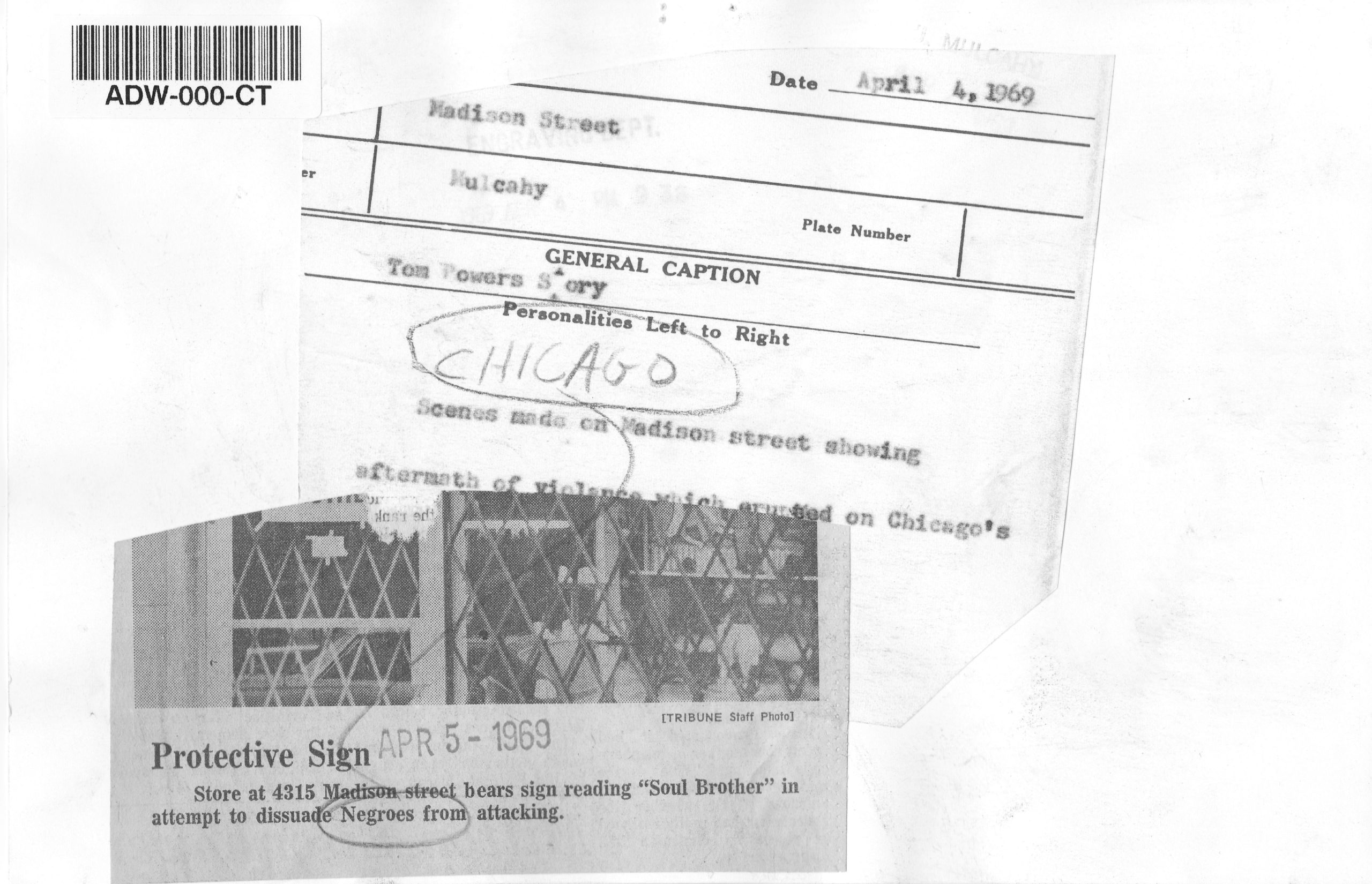

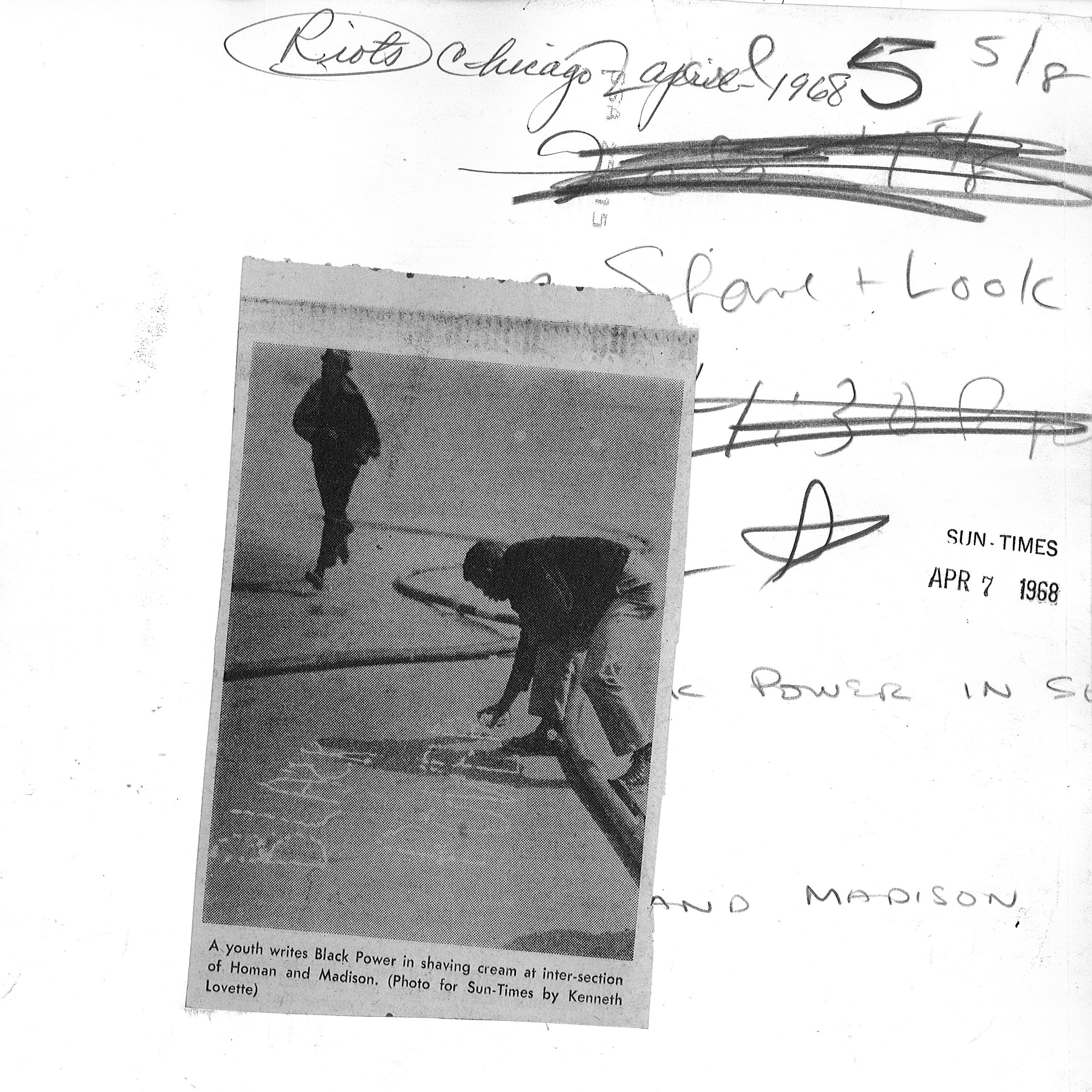

But the uprising— typically referred to as “riots”—was not simply a matter of incoherent violence. Studies done at the time suggested that people who participated in urban uprisings were not simply letting off steam but took action on the basis of a more articulated political consciousness than those who did not. This seems apparent in the image of a young man writing “Black Power” in shaving cream on the street, taking full advantage of the newspaper photographer’s presence (3.3). Rebellion became an expected part of urban life in this period, and people again broke windows and looted businesses in April 1969, on the first anniversary of the 1968 uprising (3.4). This time, Black business owners were prepared with printed signs reading “Soul Brother” to encourage looters to skip these potential targets (3.5).

Photographer unknown

Chicago Sun-Times

4/4/68

Photographer: Gary Settle

Chicago Daily News

4/8/68

Photographer: Kenneth Lovette

Chicago Sun-Times

4/7/68

AP Wire Photo

4/3/69

Photographer: Jack Mulcahy

Chicago Tribune

4/5/69