Annette Michelson and the “Crisis” of Criticism c. 1967–73

As is well-known, Annette Michelson founded October with Rosalind Krauss in 1976.[1] To commemorate Michelson’s passing in 2018, a special issue of October contained a series of contributions and reminiscences, mainly from filmmakers and academics in film and media studies.[2] The focus of this article, however, is upon Michelson’s emergence as a writer in relation to other critics and the underlying problem of critical method. Unlike some colleagues at Artforum, she was never a close follower of Clement Greenberg.[3] Michelson’s intellectual coordinates were located largely in the French intellectual culture which she helped to introduce to Anglophone art criticism upon her return to the United States in the mid-1960s.[4]

If contemporaneous art writers engaged with Greenberg, a comparably formative intellectual mentor for Michelson was André Bazin (1918–58). Her early review of the English translation of What Is Cinema? (1967) marks an early engagement with Bazin’s establishment of a critical method with which to study film and cinema. I would like to consider this review in relation to two other key critical engagements. “Robert Morris—An Aesthetics of Transgression” accompanied the artist’s exhibition at Corcoran Gallery in 1969. Although known for its critique of Michael Fried’s notion of “theatricality,” this passage constitutes only a small portion of Michelson’s lengthy text: although, as we will see, Michelson’s use of Charles Sanders Peirce against Fried’s Jonathan Edwards add different inflection to debates on modernism and “theatricality.” The polemical nature of Fried’s argument indicated a hardening of his conception of modernism, one later associated with conservatives such as Hilton Kramer. In 1974, Michelson reviewed Kramer’s collection The Age of the Avant-Garde: An Art Chronicle 1956–72 (1973). Michelson’s nuanced review was characteristic of her scrupulous approach. However, it also indicated a more nuanced understanding of the relationships between modernist critics. Taken together, these three texts provide an initial step towards a fuller assessment of both Michelson’s contribution as a critic and theorist, and the broader shift initiated by the “crisis” of criticism during this period.

Bazin as Model

Michelson produced a substantial body of art criticism before returning to the United States in the mid-1960s. She was correspondent for the New York Herald Tribune between August 1957 and March 1960, in which capacity she wrote approximately forty-five regular reviews, according to Yve-Alain Bois.[5] She also wrote approximately twenty-five “Paris Letters” for Arts magazine between December 1957 and summer 1964 and approximately fifteen “Paris Letters” for Art International between December 1962 and April 1965, some of which continued to appear after she left France. Those writings might be regarded as an apprenticeship of sorts, with the caveat that, as Bois argues, she was already an accomplished writer. Upon her return to New York she published two key texts: “Breton’s Esthetics,” in Artforum’s special issue on Surrealism, and “Film and the Radical Aspiration” in Film Culture.[6] Michelson later recalled, in Amy Newman’s oral history Challenging Art, that her contribution to the Artforum special issue “was about my return to my native country and the kind of revision and reestablishment of my intellectual coordinates and my working situation.”[7] Although one way to understand “Breton’s Esthetics” is to regard it as part of the importation of “theory” into Anglophone criticism, Michelson later told Newman that the intellectual exchange was reciprocal:

Everybody was very kind to me when I returned here. […] And most importantly of all, I was for the first time writing with a group. I had a relationship with other writers. I knew many people in Paris, but I had no real intellectual relation with the other critics. So for the first time I really felt that I was involved in a milieu…[8]

Upon her return to New York, Michelson benefitted from this intellectual companionship at Artforum, and from the avant-garde art scene of independent filmmakers.

We might trace Michelson’s intellectual formation back to her review of What is Cinema? in 1968.[9] Michelson later recalled that on reading Bazin, she thought “[here] was someone who was not saying quite the right things all the time, but his range, his project of the theorization of film and the way in which he drew upon already existing bodies of theory, rather than just providing informal protocols, could, it seemed to me, provide a model.”[10] There is an interesting analogy here with those writers influenced by Greenberg. They, too, admitted to the attraction of a historically-minded form of criticism which avoided the informality of poetic criticism.[11] For Michelson, Bazin “set standards for ambitious critical effort” in a field that had not yet developed the sophistication of art criticism and literary criticism.[12]

Bazin’s essay “The Evolution of the Language of Cinema” gave an account of its development between the 1930s and 1950s. He argued that the crucial development of the medium was not from silent film to “talkies,” but concerned a changed approach to editing and montage.[13] Bazin argued that montage tends to abstract from reality and to focus the viewer’s attention on specific details and away from the multifariousness of reality at large. Bazin favored the shot-in-depth used famously by Orson Welles and later by the Neorealists.[14] This technique created a more economical means of directing, bringing the spectator closer to the image. He also argued that it allowed for a greater degree of ambiguity. The cutting used in montage, on the other hand, tended to suggest a more precise meaning for each edited fragment.[15] Michelson, of course, would take an opposite view, championing the montage of Sergei Eisenstein and other avant-garde filmmakers. This distinction has political as well as technical ramifications. Bazin claimed that the wider shot-in-depth allowed a greater degree of ambiguity and spectatorial freedom. Michelson would return to Bazin in the essay “Screen/Surface: The Politics of Illusionism” (1972). Here, Michelson drew attention to the political implications of Bazin’s notion of montage:

It is interesting to note Bazin’s use, as an ultimate supporting argument (or rhetorical strategy) of a political metaphor: the depth of field which underwrites this ambiguity guarantees as well the more “democratic” ordering of phenomena presented. Not subjected to the subjective emphases of the more assertively edited footage and the metaphorical thrust of the montage style, the material is not in any way subject to hierarchization (or “distortion”), and the spectator retains his “democratic” right as it were, to the constitution of meaning from within that cinematic manifold… One can with a certain justice speak of Bazin’s critical and theoretical work as providing an esthetics of postwar Christian Democracy.[16]

Michelson adds that Eisenstein had his own view regarding the “democratic” viewer: he argued for “the active quality of… film-viewing experience as involved in the constant apprehension of the dialectic of contrasts and of metaphors… offering to his spectators the experience of revolutionary consciousness unfolding in the apprehension of the dialectic.”[17]

This distinction between Bazin’s realism and Eisenstein’s montage has been extensively discussed in film studies. But I want to turn here to the way that Michelson frames Bazin’s theory and its accompanying Neorealism as “the privileged mode of ontologically focused consciousness itself.”[18] Michelson moves outwards from Bazin’s distrust of montage to a whole worldview, arguing that such distrust is rooted in “the intransigently religious sensibility,” an attitude which holds that art should reveal a “transcendent reality.” This is justified in the sense that for Bazin

Poesis has ultimately to be construed as an assault upon a Primal Unity, a sin against Being itself. It was as though the Symbolist proposal of an autonomous, self-justifying and reflexive order, that Aesthetic reformation which engendered Modernism, had revived an ancient hubris, substituting for The Creation creative process as the prime and general object of piety, the source of cinematic authenticity.[19]

This cascading passage is characteristic of Michelson in full flow. Her confident inductive diagnosis of Bazin’s criticism is characteristic of formalist writing. The slightly abstruse manner of expression recalls some of the more portentous pronouncements of Abstract Expressionist discourse, but it also prefigures the ascendancy of “theory.” Is Eisenstein’s montage aligned with Symbolism and art-for-art’s sake? Not quite, although Michelson positions Bazin’s realism against a broader modernist move to repudiate it. In a grand dialectical sweep, Michelson argues that the opposition between realism and modernist fragmentation has been transcended by recent filmmakers. She points to Robert Bresson, Jean-Luc Godard and Alain Resnais.[20] To illustrate this, the concluding page of the publication in Artforum displays a still from Andy Warhol’s Sleep (1964). Here, the lengthy duration of the camera’s focus on John Giorno takes Bazin’s notion of the sustained shot to an extreme, turning this realist technique to more explicitly radical ends.

Michelson’s writings on Bazin marked a point in the development of film theory when a second generation of theorists started to turn against Bazin: a move which would lead to the development of “apparatus theory” and the use of psychoanalysis. To those critics, Bazin’s conception of realism was regarded as a mere effect of ideology.[21] This turn, as Michelson acknowledged in “Screen/Surface” in 1972, was shaped by the events of 1968. But Michelson was too sophisticated to reject Bazin wholesale; instead, she regarded him as a model to be superseded dialectically. In “What is Cinema?” she compared Bazin to Greenberg. Bazin died at the age of forty in 1958. Coincidentally, Greenberg stopped writing regular art criticism around this time. Like Greenberg, Bazin paid little heed to Surrealism or to Russian Constructivism. A further analogy worth highlighting is that, like Greenberg’s Art and Culture (1961), What Is Cinema? whittled down Bazin’s writings at the cost of losing “the central points of philosophical reference.”[22] One shouldn’t push this analogy too far: Bazin’s Écrits Complets were published in 2018. They total two thousand, six hundred and eighty-one texts (although fewer than three hundred have been translated into English).[23] Despite this far greater output, we might point to a similar pattern of reception with Greenberg: an initial formative influence, followed by a critical backlash, with later reassessments.[24]

Neither Bazin nor Greenberg were academics with fully worked-out philosophies of art or film. As such, their writings are subject to debate as to whether we can discern a broader underlying theory.[25] As with Bazin’s notion of “realism,” discussion of Greenberg has occasioned similar debates which often hinge upon well-known texts such as “Avant-Garde and Kitsch” (1939) and “Modernist Painting” (1960). Those are often taken as a shorthand for Greenberg’s broader critical positions. There is an age-old dilemma here between the practice of criticism, which entails shifting position to encounter the new, and the working-out of a philosophical theory. This is further complicated by the over-determination of those texts as they become part of an ever-growing academic literature.

Almost five decades later, Michelson’s anthology On the Eve of the Future (2017) opens with a passage from Bazin which she had already quoted in “Screen/Surface” (1972). Taken from Bazin’s brief text “L’avant-garde nouvelle,” it was first published in the tenth anniversary edition of Les Cahiers du Cinéma in 1952. Bazin responded to Hans Richter’s “Un art original: le film,” which had drawn attention to the avant-garde of the late 1920s and to recent innovators such as Maya Deren and James Broughton in the United States, whom Richter considered the inheritors of this radical tradition. Bazin, on the other hand, proposed a different conception of the avant-garde:

We may use the abandoned concept of the avant-garde if we restore its literal meaning and thereby, its relativity. For us, avant-garde films are those in the forefront of cinema. By the cinema we mean, of course, the product of a particular industry whose fundamental and indisputable law is the winning, by one means or another, of public acceptance. This may seem a paradoxical statement to make, but it carries a corrective provided by the notion of public acceptance. The avant-garde of 1949 is just as prone to misunderstanding on the part of the mass public as that of 1925… This avant-garde arouses no less hostility. On the contrary, it elicits more, because not soliciting misunderstanding, attempting as it does to work within cinematic norms, it takes great risks: both misunderstanding on the part of the public and immediate withdrawal on the part of the producers.[26]

Bazin’s argument for the neo-realists countered the filmmakers identified by Richter, who Michelson agrees were the true inheritors of the avant-garde, although she adds the names Kenneth Anger, Sidney Peterson and Harry Smith. Michelson cautions that “for those unconcerned with the important new developments… Bazin’s statement was to afford a sense of ease and intellectual progress regained.”[27] We might think here of Greenberg’s argument for the color field painters in the late 1950s and 1960s: that their sweet, airy surfaces disguised genuine avant-garde intent.[28] This went hand-in-hand with a reestimation of the late Monet as an overlooked radical. This argument by Greenberg is often regarded as opportunistic and unconvincing. We might take the positions of Bazin and Greenberg as somewhat outdated: comparable, perhaps, to T.S. Eliot’s understanding of tradition. However, that Bazin bookends Michelson’s career is telling. It demonstrates not only his intellectual importance, but that his position, like Greenberg’s, must be understood dialectically in order to arrive at a more comprehensive theorization, whether of film or of modernism more broadly.

“Robert Morris—An Aesthetics of Transgression” (1969)

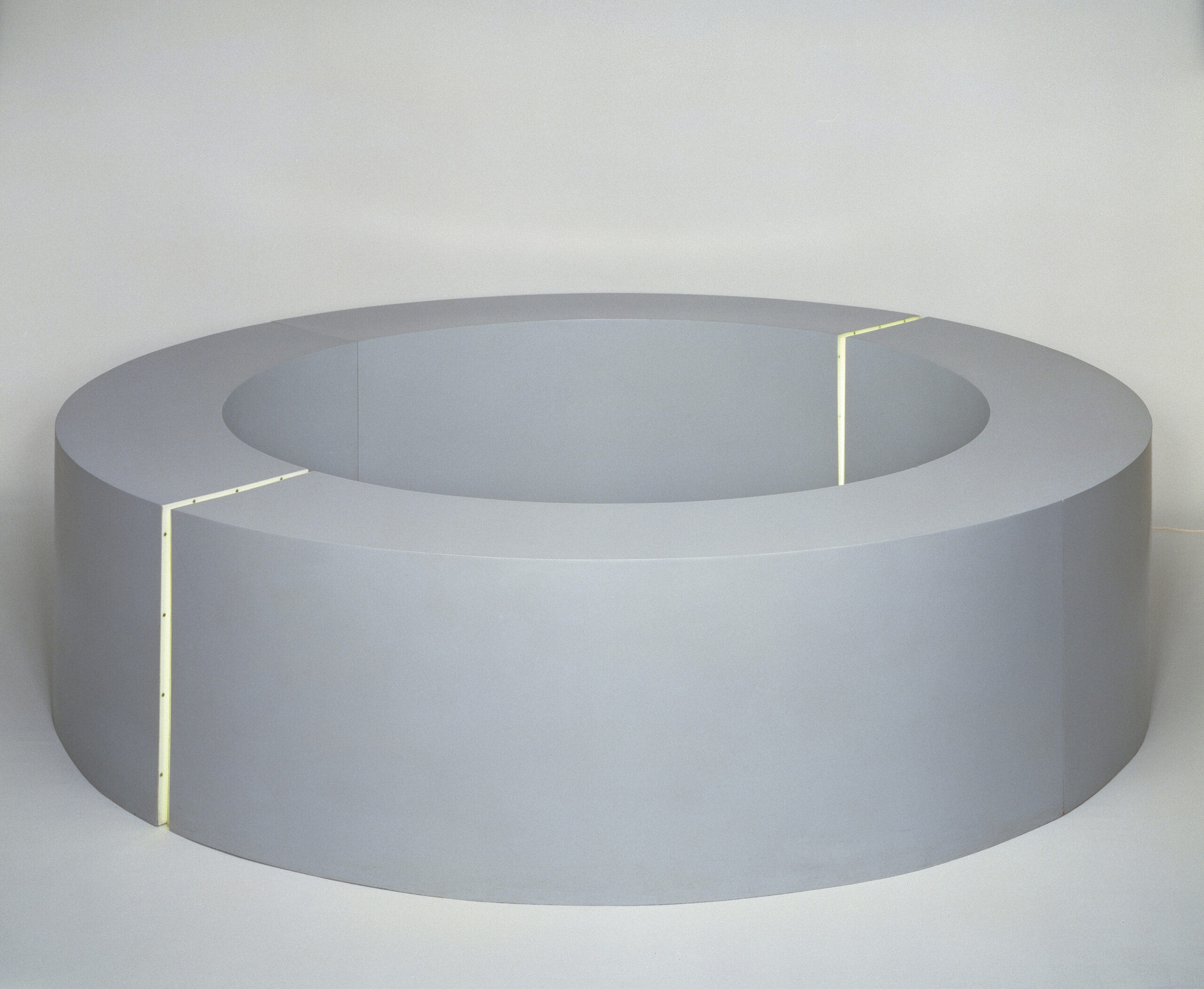

While Michelson was emerging as a formidable film theorist in the 1960s, she was also writing on the visual arts, where the dominant modernist criticism was challenged by new practices such as Minimalism. “An Aesthetics of Transgression” accompanied Morris’s exhibition at the Corcoran Gallery in 1969. The essay goes far beyond Morris: it is a dense, multi-layered text containing enough material to launch a clutch of academic careers. In its grand sweep, it might be regarded as an exemplum of the critical-historical writing which would later appear in October. At the heart of the text though, is Morris, whose work, according to Michelson, exhibited a “resistance to prevailing critical techniques founded on notions of aesthetic metaphor, gesture, or statement.”[29] The declarative nature of Morris’s work appeared to some viewers to be nothing more than “this cube” or “that slab” of unprepossessing materials, often in a non-committal gray. Jack Burnham, who reviewed Morris’s show when it moved to Detroit Institute of Arts, pointed to the “hollow-centered, circular and oval pieces” such as Untitled, 1965–66 (Fig. 1), which Burnham regarded as enduring “archetypes of the artist as a personality.”[30] He noted that the hollow center appeared to forbid entry to the viewer, “as if to say, ‘I won’t allow you near the center, the center is me.’”[31] Michelson described this apparently self-sufficient work as “apodictic,” analogous to tautological statements which “brook neither denial nor debate.” This self-sufficient, declarative quality projected a sense of security which appeared to be lacking in critical discourse. She had already gestured towards a “crisis of criticism” in “Breton’s Esthetics,” but she now diagnosed the following symptoms:

1. A general and immediate proliferation of new epithets.

2. Attempts to find historical, formal precedents which might facilitate analysis.

3. A growing literature about the problematic nature of available critical vocabulary, procedure, standards.[32]

Michelson’s text then, was an attempt to come to terms with some of the problems set in train by work termed Minimal art, “Primary Structures”—the title of the group show at the Jewish Museum in 1966—or “ABC Art,” the title of Barbara Rose’s 1965 essay. Michelson cited the following passage from Rose: “as T.E. Hulme put it, the problem is to keep from discussing the new art with a vocabulary derived from the old position.”[33] Hulme’s remark, made a half-century earlier, seemed especially pertinent to Michelson, so much so that she cited Hulme in an extensive passage. As Michelson noted, the nature of Minimal art could not be seen as simply “one more seasonal episode in an accelerating history of stylistic innovation.”[34]

Between 1967–68, Michelson wrote about a related group of artists in Artforum: Ron Davis, Agnes Martin, and the Canadian sculptor Sylvia Stone. She also reviewed the “10” exhibition at Dwan Gallery in October 1966.[35] This group show included work by Carl Andre, Jo Baer, Dan Flavin, Donald Judd, Sol LeWitt, Martin, Morris, Ad Reinhardt, Robert Smithson and Michael Steiner. Michelson’s review opened with a passage quoted from Henri Michaux’s “Au Pays de la Magie” (1941), later republished in Ailleurs (1948).[36] This story describes a fictional voyage where the narrator finds “an exquisitely cold light, invented by the Magi and displeasing to others… a brightness which is strict and clear… a light one is tempted to call ‘classical.’”[37] Anticipating the Morris text, she writes that “this exhibition evokes two matters of central interest in the situation of art just now: a current crisis of criticism and the increasing interinvolvement of artistic and critical activity. (Of the artists represented at Dwan, four, at least, have been fairly systematically engaged in critical writing.)” She also wonders about “the increasingly urgent necessity of some conceptual or philosophical framework within which criticism can propose a comprehension of the dynamics of art history and of art making.”[38] Michelson proposes that negation might be the unifying thread behind this aesthetic of “literalness,” “reduction” or “concrete reasonableness.”[39] This last term we will return to later.

Those short reviews function as a prelude to the more extensive theoretical reach of “An Aesthetics of Transgression.” The title suggests forbidding seriousness, perhaps leavened by a promise of an erotic frisson. Spread across five lengthy sections, the text has a sense of extended duration appropriate to the experience of Minimal art. The heavily edited version included in James Meyer’s appendix of primary and secondary sources in the Phaidon publication Minimalism cuts the extensive section which compares Morris to Marcel Duchamp.[40] He also removed the closing (fifth) section, which contextualized Morris within a changed understanding of the Cubist “analysis” of the object. Here Michelson refers to Constantin Brâncuși, Edmund Husserl, Kasimir Malevich, and Vladimir Tatlin.

Meyer’s edit preserves what may be the two most well-known elements of Michelson’s argument. Firstly, her framing of Minimalism—or, at least, Morris’s work—in phenomenological terms: an approach characterized by her pioneering account of Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). Indeed, as Gregory Taylor has argued, “Michelson endeavored to adapt American Minimalist criticism to the cinema.”[41] Michelson’s argument for the figuring of the viewer of 2001 as an active, corporeal presence mirrors the ways in which Minimalist discourse—and Morris especially—reactivated the position of the spectator.[42]

The second key element is Michelson’s critique of “Art and Objecthood.” There is an irony here. Michelson later remarked that she considered the essay to be Fried’s most overrated piece of writing.[43] She recalled taking copious notes at the time which she decided not to publish. In the end, Michelson’s refutation of Fried comprises only a small part of the text: although elsewhere, Michelson challenges Fried’s conception of modernism indirectly.[44] Nonetheless, the text has come to stand for a broader conflict between Fried’s conception of modernism and the emergence of a new cultural condition, once termed postmodernism, but which we might now call “the contemporary.”

Prior to Fried’s use of the term “theatricality,” the terms of this conflict were pitched between the “optical” and the “literal”: between a sensuous painterly modernism and more phenomenological practice which threatened to broach the territory of non-art. The two terms were not wholly separate, however, and, as is well-known, the painting of Frank Stella lay between those two readings. Fried had reflected upon this for some time, using the term “non-relational painting” in a 1965 essay on Stella and Kenneth Noland.[45] Their paintings tended to appear as one holistic form. In Stella’s case, the irregular shape of the canvas itself often determined the painting, as in his early black, aluminum, and copper paintings (although it should be stressed that this was not uniformly the case). In Noland’s work, despite the predominantly rectangular format of his paintings, his use of preformed concentric rings and targets, allied to his “one-shot” approach, had an effect similar to that of Stella, stressing the surface and shape to such an extent that they could be regarded as “mere” objects.

Michelson took her bearings from what Fried described as the “literalist” tendency. In the Morris essay, she “culled” a series of indicative words from the critical literature.[46] Michelson then draws the reader’s attention to the following passage where those indicative words reappear: “About (it) little can be affirmed; many of the predicates we can attach to it are negative. It is incomparable, non-relational, undifferentiated, indescribable and unintellectual.”[47] This passage might have been written by Mel Bochner, or by Morris himself. However, as Michelson writes, it is “an account of the notion of ‘epistemological firstness’ as defined by the first among our philosophers, Charles Sanders Peirce.”[48] The passage is taken from Thomas S. Knight’s study Charles Peirce (1965).[49] Although an introductory study, Knight’s account of Peirce’s many intellectual contributions is far from straightforward. The passage in question refers to the triadic structure of “firstness,” “secondness,” and “thirdness” that comprised Peirce’s phenomenology, which he termed the “phaneron.” Broadly, Knight claims that “firsts,” “seconds,” and “thirds” can be understood as qualities, facts, and relations.[50]

Peirce describes ‘firstness” as a “mere sense of quality.” The examples he adduces are singularly unpleasant: “an odour… an infinite dead ache… a piercing eternal whistle.”[51] “Secondness” is not a quality, but instead what Peirce calls “the shock of reaction between ego and non-ego.”[52] It is not a quality or a feeling, but the idea of action and resistance: our acceptance of the actual impressing itself upon us (Peirce gives the example of pushing against a door). “Thirdness” is cognitive: it is the mediation of firstness and secondness into something knowable. Although the three terms are interrelated, it is the notion of “firstness” which is especially pertinent to debates around criticism in the 1960s, when the very question of critical principles was being brought into question by works which questioned the nature or properties of art.

Although the overall structure of Peirce’s thought has an admirable clarity, the terms themselves are complex. As Knight explains, “firstness” is not a feeling (for feelings are complex), nor is it a percept (an object of perception which may be broken down and analyzed into constituent “firsts”).[53] The irreducibility of “firstness” also prevents it from being categorized with other qualities. Knight continues:

So much for what firstness is not. On the positive side, firstness is somehow “absolutely present” yet we have no absolute awareness of it. It is a “purely monadic state of feeling” which is somehow “immediate” without its being derived by reflection from what is not immediate; it is “fresh” without the necessity of deriving that freshness from the non-fresh; it is “free” without the necessity of deriving that freedom from the non-free; it is “vivid” without the necessity of deriving that vividness from the non-vivid. Firstness for Peirce is “original” and “spontaneous”—affirmations which apparently do not require their opposites.[54]

I cite this in full because Michelson’s citation abbreviates it slightly without indicating the alterations.[55] In doing so, she elides some of the complexities of Knight’s original text. Although “firstness” is not strictly speaking a quality, it might be taken in a lay sense to stand for certain properties of Morris’s art. The “singular” and “irreducible” (not to say unpleasant) aspects of “firstness” might correspond to negative critical responses. But what of the “vivid” and the “spontaneous”? Those terms are not suggestive of “literalist” art but rather of the intuitive approaches of painterly modernism. This intertwining is indicative of the complex relationship between modernism and “theatricality” more broadly.[56]

Michelson draws attention to the notion of firstness as “absolutely present,” comparing this to Fried’s “continuous and entire presentness, amounting, as it were, to the perpetual creation of itself.”[57] However, the analogy is not exact. As Knight explains, “firstness” is not a percept: it is not a bundle of properties which can be broken down and analyzed. Fried, on the other hand, is not describing the properties of modernist art but the viewer’s apprehension of what he considers to be the best modernist painting and sculpture. Similarly, the irreducibility of firstness cannot be said to apply to our experience of Minimal art. Although it appeared “singular” and reductive, Morris’s spartan forms consist of multiple perceptual properties of surface, colour, and shape, however unappealing they may be to unsympathetic viewers. We can construe “firstness” here not in a strictly Peircian sense, but rather as a term around which critical principles constellate, underpinning the explanation and evaluation of the new art of the 1960s.

Michelson ties Fried to an explicitly religious worldview, as she did in her account of Bazin. Here, “presentness” suggests not Peirce’s quality of “firstness,” but St. Augustine’s divinity (“Examine the mutations of things, and thou wilt everywhere find ‘has been’ and ‘will be.’ Think on God, and thou wilt find ‘is’ where ‘has been’ and ‘will be’ cannot be”). Michelson sets up Fried in opposition to modernism’s “secular impulse”: “Modernism seen thus assumes the aspect of a Reformation, bequeathing, in its prescriptiveness, its preoccupation with a canon, its identification of aesthetic decisions with moral choices, a repertory of Calvinist themes of sin and redemption for our contemporary rehearsal.”[58] Fried of course, had referred to the Calvinist theologian Jonathan Edwards in the epigraph to “Art and Objecthood.” Michelson’s epigraph to “An Aesthetics of Transgression,” on the other hand, cites Peirce. However, the appeal to Peirce reveals an entwining of those two positions of modernism and theatricality, religiosity and the secular impulse. Meyer made a similar claim in his magisterial study Minimalism: Art and Polemics in the Sixties (2001). He writes that Michelson’s was a “powerful reversal of ‘Art and Objecthood’s’ cherished values.”[59] But as he added, this reversal implicitly accepted the terms of Fried’s analysis by lauding the “theatrical” rather than deploring it. Meyer also argues very subtly—perhaps too subtly—that Michelson’s text reduces the complex nature of “presentness” to something of a straw man. While it is true that Fried’s essay is complex, and that “presentness” cannot be so easily dismissed, Meyer’s claim is not fatal for Michelson’s argument. However, Fried’s closing remark “presentness is grace,” was offensive to Michelson and to her ally Rosalind Krauss. It is worth noting that for Edwards, “grace” was not attained through the cultivation of sensibility (as one might assume if we understand Fried within the traditions of aestheticism and formalism). “Grace” was simply given through “God’s arbitrary and sovereign good pleasure.”[60] As Miller’s biography of Edwards shows, the notion that our good works on Earth could have the slightest bearing on God’s grace—such as proposed by the Dutchman Arminius—was considered outrageous by Edwards. Indeed, Miller’s study inveighs strongly against Arminianism’s milder variant of Calvinism as if it were a form of touchy-feely liberalism (to be classified with other misguided ideas such as democracy).[61] What then, could be further from the “secular impulse” of radical modernist practice?

It is worth turning here to the term “concrete reasonableness”: the title of Michelson’s review of the Dwan Gallery show “10” in 1967. On the face of it, it appears to describe both modernism’s “secular impulse” and the tendency of art in the 1960s, exemplified by Stella’s catchphrase “what you see is what you see.” It is also suggestive of “Concrete Expressionism,” the title of a show organized by Irving Sandler in 1965 which included work by Al Held and Ronald Bladen. But the phrase is from Peirce, and as Knight explains, it means something very different: that “the cosmos is becoming more reasonable, more settled, more lawlike, less sporadic, less erratic, and less indeterminate. […] For there is purpose operative in the universe; it is evolving toward an end—concrete reasonableness.”[62] The term signifies Peirce’s conviction of a tendency towards ever greater understanding of the lawlike workings of the cosmos. In this, Peirce’s cosmology is, according to Knight, “hyperbolic” (optimistic) rather than “parabolic” (pessimistic).[63] Edwards’s vision, on the other hand, regarded the majority of humanity as destined for the eternal fire. To take this distinction down to a less cosmic level, we can understand Michelson and Fried as occupying similarly opposed positions. Michelson’s writing evinced a (“hyperbolic”) optimism about the possibilities of radical avant-garde practice, whereas Fried’s “Art and Objecthood,” taken as a denunciation of those tendencies, is pessimistic (“parabolic”).[64] We are back then, at the accepted view of those opposed positions, although the consideration of Peirce has, I hope, added a helpful gloss to its broader stakes. What though, of the nature of criticism? Michelson described Morris’s early sculptures as “apodictic,” suggesting an imperviousness to critical debate. Apodictic propositions are demonstrably true by definition: the etymology derives from the Greek “to show.” As is well-known, one aspect of modernism’s crisis, which “Art and Objecthood” has come to signify, was the increasing difficulty of ascertaining underlying critical principles in the face of work by artists like Morris. Burnham’s review, however, drew a further inference. He argued that Morris’s irony and detachment, described by Michelson as Duchampian, was suggestive of something else: “that Morris’s sculpture is essentially criticism about sculpture.”[65] Burnham pointed to Morris’s “manipulation of the art category,” which he explained as “an overriding concern with the category of art per se, and only secondarily [with] particular art forms or inventions.” Instead of using the “found object” in the manner of Duchamp, Morris adopts a “curatorial” approach to the “found art movement” (be it Minimalist, Conceptual or Anti-Form).[66] Burnham suggests that Morris, rather than Fried, is Michelson’s genuine critical interlocutor.

“Contemporary Art and the Plight of its Public: A View from the New York Hilton” (1974)

Robert Pincus-Witten’s “Naked Lunches” contains an account of an editorial meeting at Artforum in the mid-1970s. Under discussion was Michelson’s review of Hilton Kramer’s recently published anthology The Age of the Avant-Garde (1973).[67] Lawrence Alloway, who could be prickly at the best of times, was especially irked by Michelson’s use of the word “apodicticity,” and he rudely cut her off when she attempted to explain its meaning.[68] However, as we have seen, Michelson had already used the term in her essay on Morris. There, it described the self-sufficient quality of his work, but it also stood for a kind of recalcitrant tautology resistant to prevailing forms of criticism. In the Kramer review, the term took on a different meaning. Here, it designated the hardening of the elder critic’s conservative conception of modernism. More specifically, Michelson ascribed it to his position as art editor of the New York Times, which he took up in 1965. She described it as follows:

The art editor of the Times is somewhat removed from anything one might consider an intellectual arena or a space of dialectical interaction; he is propelled toward the eminence of the cathedra. The pressures, obligations, the dynamics of the relation to the vaster public and the market foster a certain apodicticity of tone.[69]

Michelson’s carefully written passage attempts to persuade the reader that Kramer’s reactionary position was shaped by causes which extended beyond mere personal taste or choice. Instead, she suggests that both the imperatives of the market and the publication’s wider audience were determining factors. Michelson contrasts this to the earlier Kramer’s “extremely able editorship” at Arts magazine, a position he held from 1958 to 1961.[70] There, she claims, Kramer “projected a sense of shared intensity of commitment… a certain lively reciprocity.”[71] Michelson mentions Sidney Geist and Sidney Tillim, both of whom contributed to the magazine’s “Month in Review” section, but a number of other critics wrote for Kramer at Arts magazine, such as Fried, Donald Judd and Leo Steinberg. Michelson too, wrote for Kramer during this period. Kramer’s later notoriety as a neo-conservative might lead us to overlook his role as a mentor to a roster of important critics far better attuned to contemporary practice than he. And it reminds us of Michelson’s claim regarding the importance of intellectual collegiality. Kramer’s “apodictic” tone was, for Michelson, connected to his increasing estrangement from contemporary practice and debate.[72] In this respect, she links Kramer to Greenberg and Harold Rosenberg, who “all begin, by the late ’60s, to move much more closely together in the rhetoric of their defenses and rejections.”[73] During this period, Rosenberg was a regular writer for the New Yorker but he was no longer closely involved with current practice; Greenberg on the other hand was still committed to his group of color field painters and modernist sculptors, but not to other fields of advanced practice, which he termed “Novelty Art.” This was his catch-all term for the practices of the 1960s which, he argued, sought too self-consciously to appear “avant-garde.” Kramer took a similar view, and Michelson scolded him for “invoking Greenberg’s embarrassingly feeble lamentations” on the work of Morris and Carl Andre.[74] Despite these differences, Michelson felt driven to provide a more nuanced account of Kramer, whom she clearly held in high regard.[75]

Kramer’s anthology brought together a range of writings from numerous publications across sixteen years. The timeframe stretches from the nineteenth century, with sections on early twentieth-century modernism (“Germans and Other Northerners” and “The School of Paris”) before moving on to “Americans,” “Contemporaries,” “The Art of Photography,” and “Into the Seventies.” Of interest to us here is the penultimate section entitled “Critics,” which is by far the shortest, consisting of only three essays: on Greenberg, Herbert Read, and Rosenberg.[76] The essay on Greenberg, which was initially published in October 1962 as a review of Art and Culture in Arts, remains a perceptive account of the tension between taste and history which animated his criticism. That is, Greenberg’s argument for the historical necessity of abstract art ran into conflict with the critic’s own judgments: for instance, his praise for the sensuous Henri Matisse paintings of the 1920s.[77] As Kramer pointed out, this tension was also part of the critic’s function, in that, as he put it, “every critic faces the responsibility of having to discriminate between his own irrational preferences and the application of meaningful principles.”[78] This difficulty in ascertaining its “meaningful principles” lay at the heart of criticism’s crisis in the 1960s.

Kramer’s review of The Anxious Object (1964), entitled “The Strange Case of Harold Rosenberg,” was originally published in the Lugano Review. Here Kramer praised Rosenberg’s “extraordinary intelligence” and his unparalleled “abilities as a phrasemaker.” But as is customary in commentary on Rosenberg, Kramer argued that his criticism “eschewed the analysis of form as an inferior, if not an altogether irrelevant, interest.”[79] Kramer also noted that the strengths of Rosenberg’s writing often lay on the surface. As Kramer put it, “Mr Rosenberg’s criticism is widely valued more for the extravagance of its rhetoric than for the cogency of its ideas.”[80] However, Michelson observed that Kramer shared certain characteristics with those two critics. Kramer’s “historicist generalities” drew him closer to Greenberg, while on the other hand, he could be as inattentive to form as Rosenberg.[81]

For Michelson, Kramer evinced a nostalgia for French modernism which failed to think seriously enough about contemporary practice. She described Kramer as a writer of unused potential whose keen critical sense is compared to “capital which has simply not been renewed.” The terms of this renewal center upon Kramer’s Francophilia, albeit only for the first half of the twentieth century. As Michelson reminds us, French culture continued to exert an influence on the post-war period, not in terms of Cubism or Fauvism, but in terms of existentialism, structuralism and phenomenology: developments which Kramer had “responded [to] with a faint, generalized, ironic dismissal.”[82] As she remarked, Kramer was quite willing to engage with the climate of Theosophical ideas which informed the work of Piet Mondrian or Wassily Kandinsky, but not with those of Merleau-Ponty or Wittgenstein as they might be brought to bear on Morris and his peers.

Kramer indicates the historical closure of the avant-garde in his collection’s very title. The avant-garde for Kramer is tied intimately to the middle-class. Michelson adds that the terms of his admiration for the bourgeoisie rest upon its “liberalism” and “permissiveness.” Michelson argues that this misses the fact that the “structure and ascension of the bourgeoisie exact the most terrible price from the working class, and in so doing compromise the beneficiaries of that permissiveness” [emphasis in original]. Kramer fails to grasp the bourgeoisie dialectically. The terms of the avant-garde’s decline, which he attributed to Duchamp, rest on psychological terms such as cynicism. Michelson argues that Kramer fails to consider his own implication in this new situation: “the entire cultural superstructure of which artists and critics, like dealers and museum officials, are a part, forcing complicity in the decay and repression of the late capitalist era.” Kramer, like Greenberg and Rosenberg, cannot be “outside” this problematic. She concludes with Theodor Adorno:

If cultural criticism, even at its best with Valéry, sides with conservatism, it is because of its unconscious adherence to a notion of culture which, during the era of late capitalism, aims at a form of property which is stable and independent of stock-market fluctuations. This idea of culture asserts its distance from the system in order, as it were, to offer universal security in the middle of a universal dynamic.[83]

Michelson conceives here of the critic as enmeshed within, rather than safely detached from his or her broader cultural condition. The critic may also now appear as a figure of discourse to be interrogated. In this sense, we might take Michelson’s review of Kramer as a pendant to Krauss’s “A View of Modernism” (1972). Both texts were saying farewell: not to modernism as such, but to a particular type of modernism. And while both writers are associated with the formation of postmodernism, Michelson considered herself as modernist in her formation.[84] Krauss and Michelson shared, however, a commitment to resist narratives of decline: whether this meant Fried’s denunciation of the “theatrical,” Greenberg’s distaste for “Novelty Art,” or Kramer’s nostalgia for the School of Paris. This critical dialogue between Krauss and Michelson is certainly worthy of closer consideration, not least because, as co-founders of October, they played key roles in the development of what is now broadly referred to as “theory” in the visual arts.

Within this broader turn, Michelson was in dialogue with other writers. That Bazin, rather than Greenberg, was a critical exemplar distinguishes her from contemporaries in art criticism. Michelson has remarked upon the different timelines of avant-garde film compared to modernist painting and sculpture, adding a further nuance to our understanding of her place within the discourse of art criticism. Her close engagement with Morris, though, marked an important moment in the broader “crisis” of criticism. It is doubtful that Michelson was convinced by claims made for the new art’s critical self-sufficiency, but its challenge to prevailing principles undoubtedly initiated new vocabularies and frames of reference. Her review of Kramer, written on the cusp of October’s formation may appear marginal, but it is nonetheless suggestive. Although Michelson critiqued the elder critic’s conservative conception of modernist criticism, this did not entail a rejection of modernism tout court, nor the abandonment of underlying critical principles, however much they were subject to transformation.

- [1] For a variety of perspectives on Michelson’s work, see: Richard Allan and Malcolm Turvey, eds., Camera Obscura, Camera Lucida: Essays in Honor of Annette Michelson (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2000), especially Turvey’s valuable introduction, 13–34.

- [2] “Annette Michelson Remembered,” October 169 (summer 2019), 105–163.

- [3] Michelson did briefly commend Greenberg’s writing in an early review in 1959, writing that he “is perhaps the most distinguished practicing critic of his generation, certainly the most articulate, and responsible for bringing to the attention of the American public the work of Pollock, Gottlieb and a host of others.” See: Michelson, “Gottlieb Exhibition,” New York Herald Tribune [European Edition], April 8, 1959, 5.

- [4] For a broader approach to the impact of theory on American art, see: Anaël Lejeune, Olivier Mignon and Raphaël Pirenne, eds., French Theory and American Art (London: Sternberg Press, 2013).

- [5] Yve-Alain Bois, “Letters from Paris,” October 169 (summer 2019), 39. My own search within the recently digitized archives of the Herald Tribune yielded forty-one reviews by Michelson. This discrepancy may be due to the vagaries of the search algorithm.

- [6] Michelson, “Breton’s Esthetics: The Peripeties of a Metaphor, or, a Journey through Impossibility,” Artforum, vol. 5, no. 1 (September 1966), 72–7; Michelson, “Film and the Radical Aspiration,” Film Culture 42 (fall 1966), republished in P. Adams Sitney, ed., The Film Culture Reader (New York: Praeger, 1970), 404–21.

- [7] Michelson, cited in Amy Newman, Challenging Art: Artforum 1962–74 (New York: Soho Press, 2000), 154.

- [8] Ibid., 144. Emphasis in original.

- [9] Michelson, “What is Cinema?” [Review of André Bazin, What is Cinema? ed. and transl. Hugh Gray (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1967)], Artforum, vol. 6, no. 10 (summer 1968), 67–71. Republished in Performing Arts Journal, vol. 17, no. 2–3 (May–September 1995), 20–29. References are to the latter version.

- [10] Michelson, cited in Newman, Challenging Art, 231. Emphasis in original.

- [11] This approached appealed to critics in both Anglophone and Francophone spheres: see for instance, Yve-Alain Bois and his colleagues at Macula.

- [12] Michelson, “What is Cinema?” 22.

- [13] According to Bazin, montage is defined by “the creation of a sense or meaning not objectively contained within the image themselves but derived exclusively from their juxtaposition.” Bazin, “The Evolution of the Language of Cinema,” in What Is Cinema? 25.

- [14] Bazin calls this a “dialectical step forward in the history of film language.” Bazin, “The Evolution of the Language of Cinema,” 35.

- [15] This distinction is curious from an art-historical perspective as it appears to reverse the ways that modernism and realism are understood. In art history, we might regard the modernist forms of abstraction and collage as ambiguous, while realism, on the other hand, is often regarded as offering greater legibility.

- [16] Michelson, “Screen/Surface: The Politics of Illusionism,” Artforum, vol. 11, no. 1 (September 1972), 61.

- [17] Ibid.

- [18] Michelson, “What is Cinema?” 24. Emphasis in original.

- [19] Ibid., 25.

- [20] Ibid., 27.

- [21] See: Thomas Elsaesser, “A Bazinian Half-Century,” in Andrew Dudley and Hervé Joubert-Laurencin, eds., Opening Bazin (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), 9.

- [22] Michelson, “What is Cinema?” 21–22. Greenberg’s texts for Art and Culture were also rewritten.

- [23] See: Blandine Joret, Studying Film with André Bazin (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2019), and Angela Dalle Vacche, Andre Bazin’s Film Theory: Art, Science, Religion (New York: Oxford University Press, 2020), 2.

- [24] Recent accounts by Dalle Vacche, Andrew Dudley and Blandine Joret have attempted to rectify what they regard as simplifications or misinterpretations of Bazin’s thinking. Joret points to what she regards as the “lazy and deceptive” repetitions of arguments claimed to be Bazin’s and argues for the flexibility of his theory. See: Joret, Studying Film with André Bazin, 15.

- [25] Dalle Vacche argues in André Bazin’s Film Theory (2020) that a careful working-through of Bazin’s extensive writings yields a broader theory. The difficulties of this approach were anticipated by Noël Carroll, who proposed that to argue for a theory of Bazin required the drawing out of broader principles never fully elucidated by Bazin himself. See Noël Carroll, Philosophical Problems of Classical Film Theory (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1988), 103. See also Marc Furstenau, “André Bazin’s Film Theory: Art, Science, Religion by Angela dalle Vacche,” Canadian Journal of Film Studies, vol. 30, no. 2 (2021), 116–20.

- [26] Bazin writes, “Il est donc permis de reprendre à notre compte le concept désaffecté d’avant-garde en lui restituant un sens littéral et par la même sa relativité. L’avant-garde, pour nous, ce sont les films qui sont en avance sur le cinéma. Nous disons bien sur le cinéma, c’est-à-dire la production d’une industrie bien caracterisée dont il ne saurait être question de discuter la loi fondamentale qui est de rencontre d’une façon ou d’une autre l’assentiment du public. Cette affirmation pourra paraître paradoxale, mais elle se corrige d’elle-même par la notion de nouveauté. L’avant-garde de 1949 a tout autant de chance d’être incomprise du grand public que celle de 1925… Cette avant-garde n’est pas plus maudite que l’autre. Davantage, au contraire, car dans le mesure où elle ne recherche pas par principe l’incompréhension et s’efforce de s’inscrire dans les conditions normales du cinéma, elle court le pire des risques: le malentendu avec le public et le retrait immédiat de la confiance des producteurs.” André Bazin, “L’avant-garde nouvelle,” in Cahiers du Cinéma (March 1952), 17. Translated by Michelson and cited in “Introduction,” Rachel Churner, ed., On the Eve of the Future: Selected Writings on Film (Cambridge MA and London: MIT Press, 2017), xv.

- [27] Michelson, “Introduction,” in On the Eve of the Future,xvi.

- [28] Greenberg, somewhat unusually, describes the originality of Louis and Noland as “upsetting.” Greenberg, “Louis and Noland,” in John O’Brian, ed., Clement Greenberg: The Collected Essays and Criticism, vol. 4 (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 1993), 100.

- [29] Michelson, “Robert Morris—An Aesthetics of Transgression,” in Julia Bryan-Wilson, ed., Robert Morris (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2013), 10.

- [30] Jack Burnham, “A Robert Morris Retrospective in Detroit,” Artforum, vol. 8, no. 7 (March 1970), 69.

- [31] Burnham, “A Robert Morris Retrospective,” 67.

- [32] Michelson, “Robert Morris—An Aesthetics of Transgression,” 11.

- [33] Barbara Rose, “ABC Art,” Art in America (October–November 1965). Reprinted in Gregory Battcock, Minimal Art: A Critical Anthology (New York: E.P. Dunton, 1968), 282. Cited in Michelson, “Robert Morris—An Aesthetics of Transgression,” 14.

- [34] Michelson, “Robert Morris—An Aesthetics of Transgression,” 11.

- [35] See “10 x 10: ‘Concrete Reasonableness,’” Artforum, vol. 5, no. 5 (January 1967), 30–31; “Agnes Martin: Recent Paintings,” Artforum, vol. 5, no. 5 (January 1967), 46–47; ‘Ron Davis,’ and ‘Sylvia Stone,’ Artforum vol. 6, no. 9 (May 1968), 56–58.

- [36] Michelson had previously written a review on Michaux’s watercolors. See: “The Worlds of Henri Michaux,” New York Herald Tribune [European Edition], October 28, 1959.

- [37] Michaux writes, “Leur exquise lumière froide dégoût les autres… une clarté rigoureusement clarté, règne, douce à l’œil comme est doux le lait au corps de l’enfant, lumière qu’on aurait envie d’appeler d’‘époque classique.’” In Michaux, Au Pays de La Magie, ed. Peter Broome (London: Athlone Press, 1977), 77. Michelson leaves out Michaux’s reference to the light as equivalent to mother’s milk.

- [38] Michael Fried was engaging with the same questions in the 1960s. In a review of the paintings of Stephen Greene, Fried wrote that “there has been no serious discussion of the philosophical grounds on which the aesthetic of modernist painting ultimately rests—this on the assumption that such grounds actually exist…” Fried, “The Goals of Stephen Greene,” Arts Magazine, vol. 37, no. 9 (May–June 1963), 22–23. Fried’s major essays throughout the 1960s should be understood as an attempt to reckon with this problem, although this essay was not republished in Art and Objecthood.

- [39] Michelson, “10 x 10: ‘Concrete Reasonableness,’” 31.

- [40] James Meyer, ed., Minimalism (London: Phaidon, 2000), 247–50. The original Corcoran catalogue is not widely accessible (at least, not in the United Kingdom). Meyer’s edited version would have been a standard point of reference for many readers until the full-length text was republished in Julia Bryan-Wilson’s collection Robert Morris (Cambridge MA and London: MIT Press, 2013).

- [41] Gregory T. Taylor, “‘The Cognitive Instrument in the Service of Revolutionary Change’: Sergei Eisenstein, Annette Michelson, and the Avant-Garde’s Scholarly Aspiration,” Cinema Journal, vol. 31, no. 4 (summer 1992), 51. See Michelson, “Bodies in Space: Film as ‘Carnal Knowledge,’” Artforum, vol. 7, no. 6 (February 1969).

- [42] As she puts it, “It is the commitment to the exact particularity of experience, to the experience of a sculptural object as inextricably involved with the sense of self and of that space which is their common dwelling, which characterizes these strategies [of Morris] as radical.” “Robert Morris—An Aesthetics of Transgression,” 24–25.

- [43] See Newman, Challenging Art, 199.

- [44] See, for instance, the critique of Idealism on page 8. Further, on pages 21–22, Michelson posits Morris’s sculpture as a challenge to the idea of sculpture as visually apprehended. On pages 25–28, Morris’s work is seen as a “point-by-point contestation of Greenberg’s claims in ‘The New Sculpture.’”

- [45] Fried, “Anthony Caro and Kenneth Noland: Some Notes on Not Composing,” The Lugano Review 3–4 (summer 1965), 198–206.

- [46] Michelson, “Robert Morris—An Aesthetics of Transgression,” 14. Michelson refers to the well-known Bruce Glaser interview with Judd and Stella in which both artists argued in favour of “wholeness” as opposed to the allegedly “relational” quality of European art. See Bruce Glaser, “Questions to Stella and Judd,” Art News, September 1966. Republished in Gregory Battcock, ed., Minimal Art.

- [47] Thomas S. Knight, Charles Peirce (New York: Washington Square Press, 1965), 74.

- [48] Michelson, “Robert Morris—An Aesthetics of Transgression,” 15.

- [49] This title formed part of a “Great American Thinkers Series” which aimed to “present in highly readable form the flow of American thought from colonial times to the present.” Others in the series included John Dewey, W.E.B. du Bois, Thomas Jefferson, and (of particular relevance here), Alfred Owen Aldridge’s Jonathan Edwards (1966).

- [50] Knight, Charles Peirce, 66.

- [51] Peirce, cited in Knight, Charles Peirce, 74.

- [52] Knight, Charles Peirce, 78.

- [53] Ibid., 75.

- [54] Ibid.,75–76. Cited in “An Aesthetics of Transgression,” 15.

- [55] Michelson transcribes the passage as: “Firstness is somehow absolutely present. It is a purely monadic state of feeling and somehow immediate, without its immediacy being derived by reflection from what is not immediate. It is fresh, free, vivid, original, spontaneous.” Michelson, “Robert Morris—An Aesthetics of Transgression,” 15.

- [56] See Stephen Melville, “On Modernism,” in Philosophy Beside Itself: On Deconstruction and Modernism (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1986), 3–33. See also Meyer, “The Aesthetics of Doubt: ‘Art and Objecthood,’” in Minimalism: Art and Polemics in the Sixties, 229–312.

- [57] Fried, “Art and Objecthood,” in Art and Objecthood: Essays and Reviews (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), 167.

- [58] Michelson, “Robert Morris—An Aesthetics of Transgression,” 16.

- [59] James Meyer, Minimalism,239.

- [60] Those words are from Edwards’s sermon of July 8, 1731, quoted in: Perry Miller, Jonathan Edwards (New York: Meridian, 1959), 29.

- [61] Miller describes Arminianism as “shallow optimism.” Miller, Jonathan Edwards, 123–24. In Miller’s closing chapter it is worth noting quite how extraordinarily pessimistic is his view of human nature. It is from this closing chapter that Fried takes his epigraph.

- [62] Knight, Charles Peirce, 143.

- [63] Ibid., 147.

- [64] One could qualify this by pointing to critics of Fried who might describe his rhetoric as hyperbolic.

- [65] Burnham, “A Robert Morris Retrospective,” 71.

- [66] Ibid., 75.

- [67] Michelson, “Contemporary Art and the Plight of its Public: A View from the New York Hilton,” Artforum, vol. 13, no.1 (September 1974), 68–70. Review of Hilton Kramer, The Age of the Avant-Garde: An Art Chronicle of 1956–72 (New York: Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, 1973).

- [68] Robert Pincus-Witten, “Naked Lunches,” October 3 (spring 1977), 116.

- [69] Michelson, “Contemporary Art and the Plight of its Public,” 68.

- [70] Prior to this, Kramer was Managing Editor from 1955–58.

- [71] Michelson, “Contemporary Art and the Plight of its Public,” 68.

- [72] Mira Schor has noted that in Emile de Antonio’s film Painters Painting (1973), Kramer is filmed seated behind his desk. This gives the impression that he is barricaded behind it, as if to fight off the forces of barbarism. See Schor, “Robert Hughes and Hilton Kramer,” Artforum, vol. 51, no. 6 (February 2013), 56.

- [73] Michelson, “Contemporary Art and the Plight of its Public,” 69.

- [74] Ibid.

- [75] Indeed, Michelson took offense at Roger Shattuck’s “appallingly cavalier and vulgar” review in the New York Times. “Contemporary Art and the Plight of its Public,” 68. See: Roger Shattuck, “The Age of the Avant-Garde,” New York Times, January 6, 1974.

- [76] See “A Critic on the Side of History: Notes on Clement Greenberg”; “The Contradictions of Herbert Read”; “The Strange Case of Harold Rosenberg,” in The Age of the Avant-Garde, 499–516.

- [77] Or elsewhere, his diffidence towards the work of Frank Stella, which could be taken as a logical “working-out” of his understanding of painting’s tendency towards flatness.

- [78] Hilton Kramer, “A Critic on the Side of History,” 502.

- [79] Kramer, “The Strange Case of Harold Rosenberg,” 512. This is a view of the critic which has persisted, although there have been recent efforts to rectify it. See: Christa Noel Robbins, “Harold Rosenberg on the Character of Action,” Oxford Art Journal, vol. 35, no. 2 (2012), 195–214.

- [80] Kramer, “The Strange Case of Harold Rosenberg,” in The Age of the Avant-Garde, 511. For a persuasive and more sympathetic account of the notion of “rhetoric,” see Robert Genter, Late Modernism: Art, Culture and Politics in Cold War America (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2010). In particular, see chapter 8, 273–308.

- [81] Michelson, “Contemporary Art and the Plight of its Public,” 69.

- [82] Ibid., 70.

- [83] Theodor Adorno, “Cultural Criticism and Society,” in Prisms, transl. Samuel and Sherry Weber (London: Spearman, 1967), 22.

- [84] Michelson told Amy Newman that she did not regard herself as having engaged in debates around postmodernism. Newman, Challenging Art, 443.