Classing the Classics: Investigating Artisanal Reproduction of Landscape Imagery in Nineteenth-Century Chinese Tombs

Introduction: Putting the Class in Classics

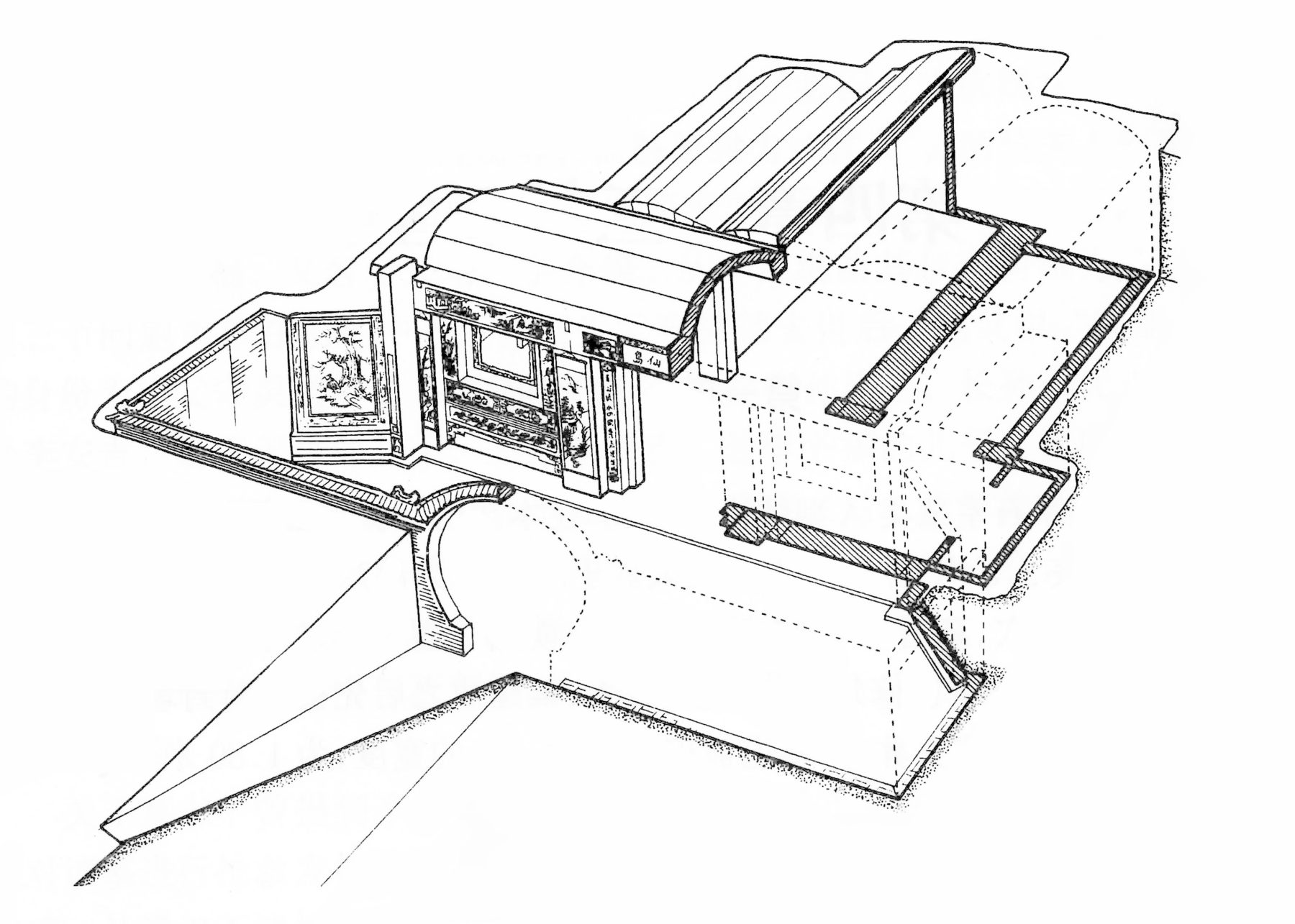

In 2001, five extravagant nineteenth century stone-carved tombs were excavated in Bayu Village of Dali County in Shaanxi Province, an inland region in northwest China. These underground eternal residences belonged to a well-off merchant and local elite family with the surname Li.[1] The tombs are primarily assembled from carved limestone slabs, and each underground unit consists of a tomb pathway, a walled courtyard, a main hall with or lacking two side chambers, and burial chambers for the coffins (Fig. 1). The most stunning feature of the Li family tombs is their close replication of aboveground house structures and the realistic representations of architectural decor, wooden compartments, scroll paintings, calligraphic couplets, screens, embroidered valances, furniture, and other decorative objects. The pictorial details of landscape painting or, in Chinese, shanshui hua (mountain and water painting) and the material forms of hanging scrolls and screen panels are especially striking as these are meticulously reproduced on the surface of the limestone. A pair of calligraphic couplets engraved along the entrance of the burial chamber for Li Tianpei (the posthumous name for Li Jingfu, 1830-1875) explicitly indicates that his erudition in classics is a pre-requisite of his stone chamber’s ability to secure his transcendence to the immortal island of Penglai. The first lines read: “This place is connected to Penglai; he is so knowledgeable that he can transmit the classics to construct a stone chamber.”[2] By the time of the nineteenth century in China, “transmitting the classics” (chuanjing) and “stone chamber” (shishi) became standard elements in expressions that uplifted a member of the gentry’s contribution to local cultural enterprise. Nonetheless, when such rhetorical clichés were materialized through lavish stone carvings, the materialization itself might flag one important question: How did the merchant class utilize the “classics” for constructing a tomb in order to reach eternity? Furthermore, although artisans’ names remained anonymous, their techniques of carving are embedded in the simulations of scholarly paintings, which provides evidence of the Li family’s artistic currency. This leads to a second question: how do we understand the role of artisans in this making process?

1. Structure of Li Tianpei and his wives’ tomb, line drawing after Shaanxi sheng kaogu suo, Dali lishi jiazu mudi (Xi’an: Sanqin chubanshe, 2003), 46, pl. 42.

In this essay, I would like to rethink the shifting relations between literati, merchants, artisans, and other social actors in late imperial China and discuss the reconstitution of class-formation within the reception and constitution of the classics. I examine the phenomenon of class-formation within the classics by focusing on a material turn taken through transmedial practice, namely from painting and prints to stone carving. Working from Li Tianpei’s tomb, in which more than twenty landscape images are carved on stone slabs using hanging scroll and screen formats, I will explore how monetary currency mediates artistic currency and how a sophisticated gentry-merchant patron and skilled artisans together manipulated various themes and styles in traditional landscape paintings and combined with literary canons to create a posthumous paradise.

In premodern China, we can understand class according to both cultural and socio-economic status. Specifically, the literati elite included poor scholars, wealthy landlords, officials, and scholars from merchant families. Their aesthetic sensibilities played an important role in establishing their identity. This model presents a possible disconnect between wealth and status: A scholar might live modestly, but would maintain his elite status. However, by the late imperial period, a significant change occurred once the power of abstract wealth or money could buy status and symbolic power, a development that had previously been morally unacceptable. Art played a crucial role in this process.

The category of “classics” associated with Li Tianpei’s tomb is abstract, ambiguous, but also inclusive and popularized in ways that go beyond conventional definitions of intellectual schools such as Neo-Confucianism. The classics are not always consciously theorized but have permeated through to everyday practices that are then externalized through visual materials. So, aspects of the classics, such as righteousness, are pre-reflectively incorporated into artworks without being made completely explicit. This does not imply that practitioners have no idea about what they are expressing; rather they might encounter and internalize ideas associated with the classics through popular media such as vernacular stories and operas. The various decorative motifs in Li Tianpei tomb showing filial piety stories, historical narratives of well-known scholars, Tang poems, landscapes, flowers and birds, utensils related to scholarly life, and many other themes are part of this everyday culture of the “classics” and become material evidence of Li Tianpei’s erudition. Hence, the image of him as a gentry-merchant with cultural currency parallels the landscape and other subjects in his tomb, which draws on a mixed canon to create eternal peace.

Two material conditions made the Li tomb possible: The merchant patron’s wealth enabled him to access and appropriate conventional landscape painting motifs and other subjects as a visual aid for transcendence to paradise.[3] And highly skilled artisanal labor capable of executing the patron’s demands converted that conventional landscape to spiritual landscape imagery. The classical forms fall into the dialectical relationship between production and consumption, which is mediated by a culture that legitimates and gives it a symbolic value. In other words, value initiates a dynamic that sets the above production process in motion. Merchants were interested in the classics because of their symbolic value, endowed by the literati. Without the merchants’ patronage, artisanal labor would not begin to transform materials, limestone in this case, into images on classical themes. However, deprived of artisans’ knowledge of stone and skill in carving, the inter-medial translation of the classical forms from paper to stone would not have been achieved either. In light of these relations, we need to look at the classics as an intersection of three social classes: merchants, literati and artisans.

Landscape Images as Funerary Landscape Paintings

The landscape images are strategically arrayed in the tomb constructed for Li Tianpei and his four wives, as I will elaborate in the following sections of this essay. These landscape images clearly follow scholarly conventions in terms of their subject, compositional scheme, brush style, and material forms. The unusual level of faithfulness to style makes one wonder whether these carvings of hanging scrolls and screens were copied from real objects, except for the fact that almost no names of the painters or artisans have been discovered. However, the landscapes in Li Tianpei’s tomb also evoke another long-established tradition in Chinese tomb art, namely spiritual painting or minghua.[4] This term refers to a painting that was created only for the dead. It facilitates the deceased’s journey to an eternal world and defines a tomb space as a posthumous paradise. Spiritual painting should be understood under the category of mingqi or spiritual articles that are made for the deceased in China.[5] As Wu Hung points out, “verisimilitude—‘the quality of appearing to be true or real’” has long been developed as a method in China to create tomb objects and space.[6] Although the category of spiritual articles has been recognized since ancient times, the tradition of spiritual painting became known to scholars in modern times thanks to archaeology carried out in China in the late twentieth and the twenty-first centuries, and especially in the aftermath of rapid economic growth in China over the past four decades. More and more tombs have been uncovered with China’s massive real estate expansion and nonstop digging. In other words, these underground landscape images were not part of the canon before the twenty-first century. One of the earliest surviving landscape murals, dated to 738, was discovered in the tomb of Li Daojian (685-738), the great-grandson of Emperor Gaozu (566-635), the founder of the Tang dynasty (618-907). The tomb, located in Fuping County, is only one hundred miles away from the Li family burial site under consideration here, though a thousand years lies between them. Unlike the under-studied Li family tomb from the late Qing period, the eighth-century landscape murals quickly drew the attention of art historians. The different treatment of the eighth-century and the nineteenth-century Li tombs is provocative with respect to how it is related to the Chinese landscape canon.

In a recent article, Wu Hung has proposed a new conceptual frame, namely “funerary landscape,” to call our attention to the dual existence of aboveground and underground landscape images from the early development of landscape genre in China.[7] He uses the term “simulated shanshui paintings” to elucidate the relationship between these two types of landscape paintings. The one for the dead is a simulation of the painting for the living. The simulation includes subject, composition, style, and material format of paintings used in the worldly world, yet in order to distinguish the painting for the dead from the painting for the living, pictorial elements are changed. Li Tianpei tomb’s landscape reliefs should be viewed under this category of funerary landscape painting. As I will demonstrate in the rest of this essay, these images closely simulate their contemporary aboveground landscape painting practices, but with careful alterations to cope with posthumous needs.

By the mid-nineteenth century, the canon of Chinese landscape painting had already been established and the markers of literati landscape were usually understood in terms of a painter’s stylistic lineage with past renowned artists.[8] From the late Northern Song dynasty (960-1127) onward, such lineages were recognized in a painter’s imitation of early models. Angered at the Mongols’ conquest of China in the Yuan dynasty (1279-1368), some scholars who had been government bureaucrats refused to collaborate with the Mongol rulers and established themselves instead as amateur painters. These literati painters chose landscape as the most suitable subject for their self-expression.[9] Painters and critics from the succeeding Ming dynasty (1368-1644) over time selected which paintings would be known as the exemplary models. As James Cahill points out, from the beginning to the middle of the Ming, the artist’s choice of a previous model was not merely connected to aesthetic preference, but intimately related to how a certain style could reflect an artist’s literary accomplishment.[10] Such literary achievement was further conflated with quasi-religious elements of the different schools, with the goal of reaching enlightenment in Chan Buddhist practice. The Southern School promoted intuitive and sudden enlightenment and the Northern School believed in gradual and cumulative realization. Several painters and theorists such as Mo Shilong (1537-1587) and Dong Qichang (1555-1636) classified the landscapes in two groups, those created by amateur painters and those created by professional painters, to contrast the artists’ different working processes. This was another framework for distinguishing the Southern and Northern schools: the former being impulsive and the latter prizing forethought and craft in brushwork. During the early Qing dynasty (1644-1911), court artists who embraced the lineages of amateur painters eventually became orthodox, and the original creative process of the Southern School was lost in this normalization.[11] Landscape paintings from the nineteenth century have been generally viewed as continuous with those of the eighteenth century; they have been dismissed as conservative and less innovative by scholars from the twentieth century. Nonetheless, recent reassessments of art produced from this time period have shown various regional creations and artistic innovations.[12]

The “classic” landscapes in Li Tianpei tomb are not limited to a particular kind of masterpiece or certain artistic school, but instead mix various classical brush idioms and compositional schemes that can be associated with past master painters of a wide range of styles. Such a mixture also includes famous literary allusions, historical narratives, ancient poems, and ideas from different religions. Here the notion of classical form is inclusive and indeed reflects the need to transport the dead to a hybrid vision of eternity.

Moreover, when the medium, artists, and space cross from paper/silk to stone, from individual painter/regional school to unknown artisans, from scholarly studio to artisanal workshop or construction site, from a worldly space to a tomb, the imitation of classic themes both serves the purpose of transcendence and materially models it. Although decorative arts created for a living space also carry allegorical functions of either cultivating a sense of one’s mortality or facilitating contemplation of a reclusive life, a landscape painting cannot satisfy the goal of utmost transcendence in an aboveground household. The material production of classic landscape imagery in Li Tianpei’s tomb entailed a process of converting decorative objects into the ritual paraphernalia of immortality.

When landscape murals from Tang dynasty tombs were excavated—murals also created by anonymous artists or artisans for a burial context—the desire to assimilate these murals into the canon of Chinese landscape painting was readily apparent. Art historians analyzed them from the vantage of intellectual discourse on landscape and brushwork as well as philosophical discussions on nature.[13] From this we can see that when the criteria for judging classical landscape paintings stabilized in the late imperial period, the canon became very exclusive, and modern scholars remain in the thrall of literati discursive hegemony. This essay attempts to destabilize that hegemony by making its assumptions visible through intermediality.

Li Tianpei as a Gentry Merchant

The five excavated Li family tombs were built between 1842 and 1875, a period of great turmoil, when Qing China was defeated by British and French armies in two Opium Wars (1839-1842, 1856-1860). Immediately following the national crisis, between 1862 and 1873, brutal conflicts between Han and Hui (Chinese Muslim) people in Shaanxi, Gansu, and Xinjiang, including Li family’s hometown in Dali County, caused the deaths of millions of people of both ethnic groups. Several male members of the Li family were killed during those massacres.[14] The construction of such an elaborate underground home may have been a way to create a peaceful space contrasting with the disastrous world above ground.

The Li family was one of the wealthiest in the southern Shaanxi region. Even in the face of social chaos, Li family enterprises continued to grow, and they traded a wide range of products from textiles to salt to grains. Their chain of shops was widely distributed across northwest China.[15] Most male members of the Li family were educated, but not enough to pass the official exams; some Li men obtained honorific official titles by donating money to the local government. Among them, Li Tianpei was exceptional in his passion for books and the arts. His epitaph, carved with his biographic information, reveals that he was born eager to learn and was a diligent student when he was young. However, he had to take on the duty of managing the family business and gave up studying, presumably diverging from a path leading towards taking the imperial examinations. He lamented his inability to attain a scholar-official career throughout his life.[16] This is perhaps the reason that his biography on the tomb epitaph leaves his success in trade unmentioned but eulogizes his charity work and his engagement in literati activities—befriending scholars, enjoying conversation on histories and ancient masters’ thoughts, and collecting paintings and calligraphy.[17] Li Tianpei was also well respected for donating money to renovate the local Confucian Temple in Tongzoufu, building roads, and sponsoring poor scholars on their trips to take the official exams.[18] According to Confucian political theory, the wide range of charity works were already considered as a performance of good deeds for reaching immortality in the Eastern Han period (25 B.C.-220 A.D.). Such moral discourses and practices continued into late imperial China.[19]

As I discussed in the beginning of this essay, in the tomb couplets decorating the entrance of Li Tianpei’s burial chamber, the phrases “transmitting classics” and “stone chamber” are used to praise his learning and charity works. The loaded term “stone chamber” can refer to a secure space in a library where documents are stored, a stone casket that holds spirit tablets in an ancestral temple, a lecture hall for teaching classics, a stone tomb, or a Daoist grotto heaven that would have naturally formed architectural elements and stone furniture.[20] Thus by layering the concepts of constructing a library / tomb / Daoist grotto—thanks to this merit-making—Li Tianpei would be able to reach Penglai, that is, eternal paradise. This result is further confirmed by the second line of this couplet, which explains that “His name is registered in the ledgers of immortals; he is so talented that he can compose fu to eulogize the Great Overarching Heaven.”[21] It means he could fully enjoy the literary composition of fu, a literary form that combines both poetry and prose.[22]

Whether stone was used as a surface incised with characters, as in the case of inscribed stone steles and rock cliffs, or used as a mineral material to create a wide range of utensils like inkstones, seals, brush holders, brush containers, and paper and scroll weights, stone as a medium was integrated into the literati’s material life.[23] More importantly, Dorothy Ko alerts us to one important phenomenon in early modern China, which is the “episteme of ‘the craft of wen’ (word, writing, male literati culture).”[24] Her research on inkstone carvers, collectors, and connoisseurs in early Qing China reveals that some scholars took pleasure in both writing and crafting as well as in writing about craft. The “craft of wen” sublates the distinction between literati and people engaged in crafts. Taking this term seriously entails that we should consider painting and other arts associated with the literati also as crafts, with emphasis on their material dimension. However, at the same time, given that these scholars also participated in what we conventionally call crafts and took these embodied practices seriously, we should also speak of the wen of crafts. In this sense, working on crafts and on material objects such as stones itself entails the skills of a literati. From this perspective, rather than an absolute separation between these two practices, we should rather think of different constellations. Although there is no evidence to show that Li Tianpei was physically involved in stone carving, his collaboration with stone artisans can be viewed in the vein of scholarly practice.

Calligraphic and Graphic Tomb Couplet | Entering the Mountains

The spatial navigation from the façade of the main hall to its interior, then to the burial chambers, parallels the bodily movement of entering the mountains, residing in the deep mountains, and then climbing to the peaks of immortality and completing transcendence. In other words, the gradual elevation of body is symbolically indicated by the subject on each individual landscape. Contrary to early examples where only one or two landscapes were used to explain the navigation of the whole tomb, the tomb designer, or perhaps Li Tianpei himself, used the idea of hanging scrolls and screens (moveable decorative arts) and displayed them in a way to facilitate progress along a spiritual path.

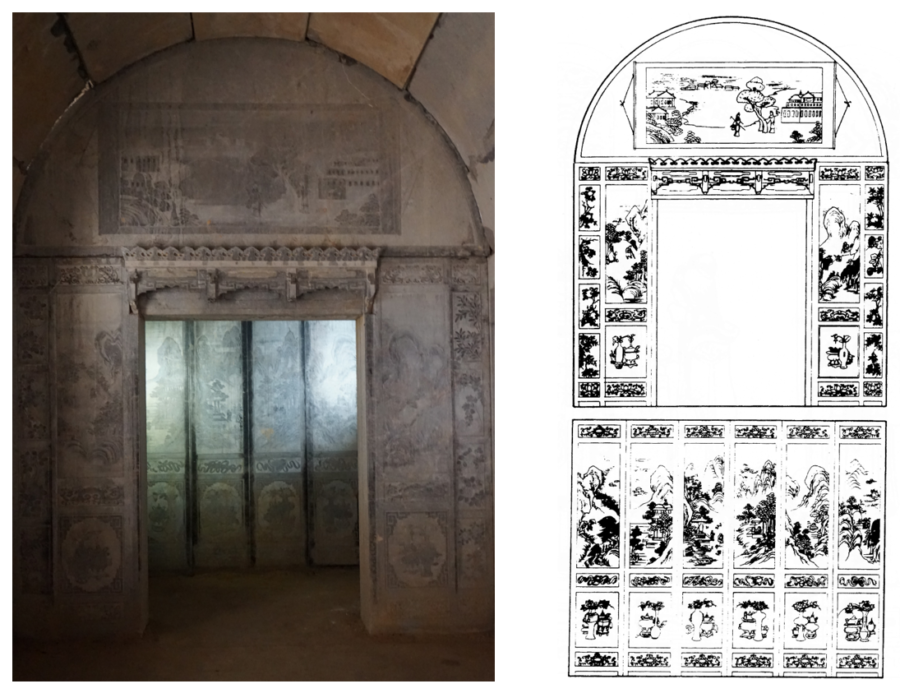

2. The façade of the entrance of Li Tianpei and his wives’ main tomb chamber, limestone, constructed between 1870-1875. Photo courtesy of Li Haoxun.

The first two landscapes, which I have named “Entering the Mountains” on the right and “Entering a Temple” on left, are arranged symmetrically on either side of the main chamber door and paired with the tomb couplet (Fig. 2)[25]. In late imperial China, a horizontal calligraphic plaque and a vertical couplet were often used to define the anterior of a building and an interior entryway. This literary and calligraphic practice enriches a wide range of architectural spaces with a poetic sense or eulogizes their human and spirit inhabitants. The plaque above the door to the main chamber in Li Tianpei and his wives’ tomb is incised with the four characters “Immortal Island of Yingzhou,” a fabled locale in Daoism later associated with one of the islands at the eastern end of the Bohai Sea.[26] As the first plaque of the tomb, it announces that behind the façade is a world beyond the living, a land of immortality.

The couplet reads as follows, right to left:

Emerald-green cypresses and dark green pine trees, a belt of thick shade protects the field of longevity;

Blue mountains and green rivers all around, an elegant atmosphere embraces the beautiful citadel.[27]

“The field of longevity” and “the beautiful citadel” were common expressions referring, respectively, to graveyards and the tombs below. Such standard phrases were often used to decorate aboveground grave structures and praise the surrounding environs as an auspicious and peaceful place for the dead. Many scholars have pointed out the connection between Chinese landscape image-making and the practice of geomancy (in Chinese contexts, the art of arranging buildings in an auspicious way) both on a terminological level and on the level of visual culture. For instance, in his discussion of geomancy and land in the Ming period, Craig Clunas has explained that although there was criticism of geomancy as superstitious knowledge by elite intellectuals, this was not “the same thing as rejection of the cosmological principles that were supposed to supply its explanatory force,” and educated people would “have accepted at least grave geomancy as being… a ‘necessary evil.’”[28] Indeed, “mountains and waters” (shanshui) is one of the terms used for geomancy in the Ming sources.[29] Susan Shih-Shan Huang further shows that geomantic principles pertained in a landscape painting discovered in the Yemaotai tomb from the Liao dynasty (916-1125).[30] Li Tianpei’s tomb continues that tradition.[31]

Hanging scrolls, while portable, are never hung on the exterior wall of a building. The juxtaposition here of a tomb couplet and a pair of landscape scrolls reveals a new mode of marking the sacredness of a tomb entrance. The isomorphism between text and image helps us recognize how a classical landscape painting for the living was converted into a spiritual landscape for the dead and, more specifically, to illustrate the geomancy of the graveyard. The tomb and graveyard mentioned in the couplet can be subtly implied within landscape prototypes.[32]

The overall composition of the two landscapes follows visual convention. Both hanging scrolls present the usual left-and-right spatial organization. As a pair, they mirror each other loosely with respect to terrain, water, and void spaces, and they maintain a sense of bilateral symmetry within the format of the door, plaque, couplet, and scrolls. Both landscapes have a rocky massif in the foreground and the concave slope leads the eye to buildings in the open spaces in the middle ground. The typical treatment of extending space into depth via hazier mountain peaks, rivers, and clouds in the background is also well reproduced. The representation of the watercourse, bridges, and a building that backs onto the mountain and faces water, may have a double function: mimicking a general landscape and satisfying some common geomantic principles.[33]

3. “Entering the Mountains” (detail of the building), façade of the entrance of Li Tianpei and his wives’ main tomb chamber, 145 x 49 cm, limestone, constructed between 1870-1875. Photo by the author.

Moreover, some of the manmade structures, objects, and figures appear unusual. On the right scroll, the three peculiarly blank mausoleum-like buildings (one of them apparently on a terrace of some sort) in the middle ground are distinct from the Chinese-style wooden, brick or thatched structures often depicted in Chinese landscape painting (Fig. 3). The treatments of the roofs, the smooth surface of walls, frameless windows, simple contour lines, and light gray hue shared with the mountain rock nearby indicate that these buildings represent stone structures and evoke a sense of concealment and timelessness. They seem to be a visual reference for the “field of longevity” on the tomb couplet and the term “stone chamber” that appears in the couplet outside Li Tianpei’s burial chamber. More intriguingly, the vaulted roof on the rear building even echoes the arched shape ceiling of Li’s tomb itself. The stone buildings are embraced by the mountains, woods, and waters, a setup that corresponds to the geomancy of the tomb eulogized in the couplet. A landscape beyond human time is successfully evoked through isomorphism between the tomb couplet and the image on the hanging scroll.

4. “Entering A Temple” (detail of the building), façade of the entrance of Li Tianpei and his wives’ main tomb chamber, 145 x 49 cm, limestone, constructed between 1870-1875. Photo courtesy of Li Haoxun.

Similarly, the left hanging scroll presents a temple-like structure situated prominently next to water in the middle ground (Fig. 4). This architecture corresponds to the “beautiful citadel ”—a synonym referring to the graveyard and tomb—in the left couplet. Then the question is why a temple-like structure would signify the idea of a graveyard or even a tomb? The peculiar style of the building is clearly intended to be special. All the unusual elements—the elongated verticality of each section, the elaborate lotus-jewel motif that crowns the narrow tower, the plank construction of pillars, walls, roofs and ridges, the sharp ridge ornaments, and a bridge-like structure extended beyond the frame—suggest that this building might represent a mix of permanent and temporary architectural forms common in mortuary practice, such as an extravagant stone tomb stele erected on the burial site, the temporary memorial tent, which often mimicked a Buddhist hall, and even paper-made towers that would be burned for the deceased. All these structures served the function of safeguarding the dead on his way to the other world and produced an “immortalizing effect.”

5. “Entering the Mountains” (detail of the figures), façade of the entrance of Li Tianpei and his wives’ main tomb chamber, 145 x 49cm, limestone, constructed between 1870-1875. Photo courtesy of Li Haoxun.

Moreover, some of the minute visual elements are altered to convert a conventional landscape into a spirit landscape. On the righthand scroll “Entering the Mountains,” in the lower center, three figures meet on a bridge that leads the way into the mountains (Fig. 5). An elderly man with a long beard looks up in the direction indicated by the other two. He wears a full-length robe, a common archaic-style garment for a gentleman, but the robe closes with left lapel over right, one of the major differences between a spirit garment for the dead and clothes for the living. This convention has long been adhered to by Confucian scholars as proper in death rituals.[34] Although it is too soon to argue that this man is a portrait of the tomb’s occupant, such a minute detail may signify the tomb occupant allegorically and indicate his journey into the mountains, the land of immortality.[35] Indeed, the theatrical identification between the tomb’s occupant and classical figures, whether generic or historical, or from a landscape or a historical narrative, has been consistently established in this tomb. For instance, the high-relief sculptures of filial piety stories along the top of the tomb’s facade loosely echo Li’s life experience.[36]

6. “Entering A Temple” (detail of the boats, streamer-shaped masts, boatman), façade of the entrance of Li Tianpei and his wives’ main tomb chamber, 1 45 x 49cm, limestone, constructed between 1870-1875. Photo courtesy of Li Haoxun.

On the left scroll image, “Entering a Temple,” two scholar-like figures stand on an open ground in front of the elaborate building. Their hands point in different directions: the fellow on the right points to a target rendered on top of the hanging scroll and the left figure gestures toward the architecture to his left (Fig. 4). This combination of two different orientations bridges two elements: the boats and the building. Following the direction suggested by the figure on the right, next to the promontory, we see several boats floating downstream. A boatman, instead of poling, stands on the lead boat with one hand raised to shade his eyes and the other hand resting on his hip to convey an upward gaze, an action that is alien to conventional boatman imagery (Fig. 6). One intriguing detail here is that where sails attached to the mast are usually represented as triangular shapes, here they are replaced with streamers on which lotus petals are gently incised. The streamers may be connected to Buddhist and Daoist streamers of zhuang and fan that are often used to venerate a Buddhist or Daoist hall and mark their sacredness. A fan banner was also a common symbol used to lead souls on their way to transcendence.[37] By the nineteenth century a pair of posts were sometimes erected in front of a tomb gate for hanging streamers for the dead.[38] Such details support the idea that the boats had a practical function, to transport someone, and a symbolic meaning, the transcendence of a soul.

The architecture or the symbolic tomb becomes the destination of the boat. Hence, by introducing such elements into mortuary ritual, yet preserving the two landscapes structurally, these images serve dual functions: They mimic the classic landscape aesthetic and venerate the dead.

From Prints to Stone | Creating Ancestral Status

Beyond the façade door, the main chamber is a 2.27-by-6.27-meter rectangle with doors on four sides that lead to the burial chambers on the east and side chambers for storing burial objects along the north and south walls.[39] The main chamber combines the functions of a ritual space for venerating the tomb occupants as ancestors and an allegorical hermitage for the deceased. However, as I will argue in the following discussion, the traditional Chinese landscape as visual aid for transcendence was reserved for the husband, and an exotic illusionistic landscape was likely invented for the wives.

7. Line drawing of the two winter landscapes along the interior door frame of Li Tianpei and his wives’ middle chamber. Drawing after Shaanxi sheng kaogu suo, Dali lishi jiazu mudi (Xi’an: Sanqin chubanshe, 2003), 48, Pl. 44.

On the back wall of the façade, there are again two vertical landscape images arranged along the entrance (Fig. 7). Unlike the first two paired with the calligraphic couplet, this second pair integrates poem, painting, and calligraphy. The original models for these are likely from a painting manual entitled A Collection of Pictures to Illustrate Tang Poetry (Tangshi huapu), though the exact edition used by the artisans is unclear. This six-volume illustrated anthology was first published in the early seventeenth century as a product driven by the sudden proliferation of printed painting manuals between 1570 to 1620.[40] Huang Fengchi (active 1621-1627), the editor of this anthology, first selected poems and then invited contemporary painters to create illustrations of them in the styles of early well-known painters (these appear mostly in volume one). His fellow calligraphers transcribed the poems in a wide range of calligraphic styles; hence poetry, painting, and calligraphy are equally presented. Such an editorial strategy reflected the literati ideal of the “three perfections.”[41] However, the famous painters’ names inscribed on the illustrations were professional artists and court painters categorized as the so-called Northern School by Dong Qichang, who devalued their work.[42] The two illustrations used in Li Tianpei’s tomb are from volume two, which is missing the names of both the contemporary painter and previous master. In other words, no particular classical tradition was claimed as the model for these two landscapes.

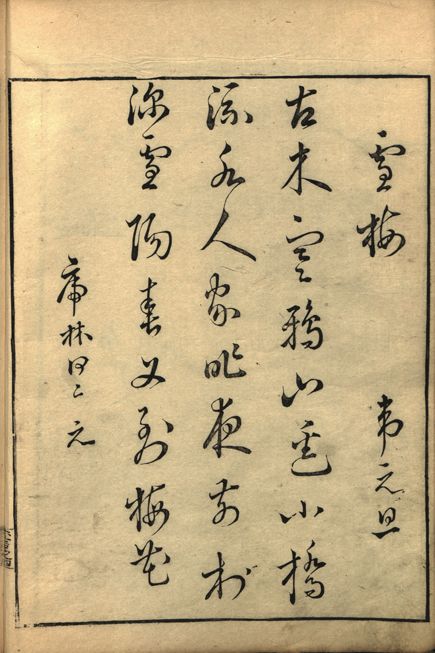

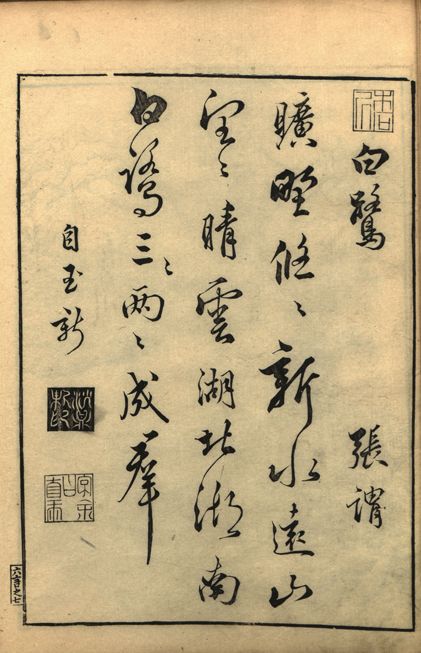

8a (far left). Poem: Wei Yuandan, “Snow Plums;” Calligraphy: He Yuanzhi. Woodblock prints. Huang Fengchi, Xinxie liuyan tangshi huapu, in Tangshi huapu, bazhong, vol.2, 4a, 1620 edition, Hong Kong Chinese University library collection.

8b (second from left). Illustration of “Snow Plums.” Woodblock prints, Huang Fengchi, Xinxie liuyan tangshi huapu, in Tangshi huapu, bazhong, vol.2, 4b, 1620 edition, Hong Kong Chinese University library collection.

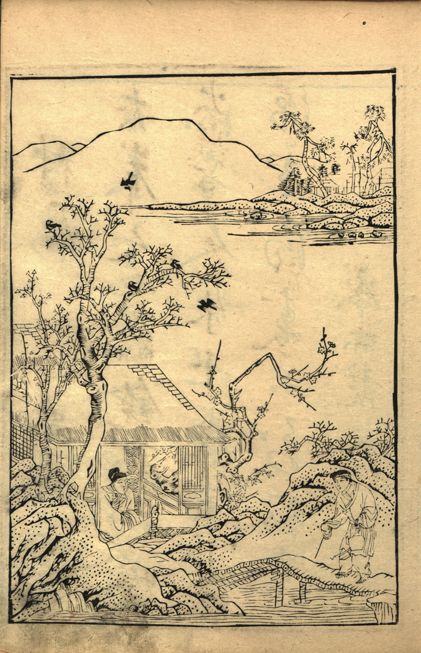

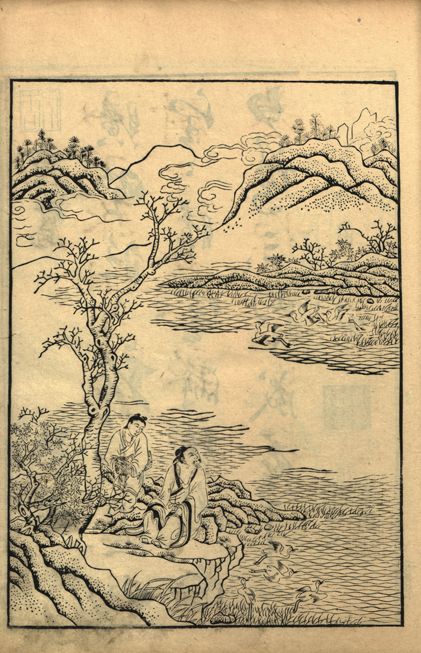

9a (second from right). Poem: Zhang Wei, “White Herons;” Calligraphy: Shen Dingxin (1573-1630). Woodblock prints. Huang Fengchi, Xinxie liuyan tangshi huapu, in Tangshi huapu, bazhong, vol.2, 7a.1620 edition, Hong Kong Chinese University library collection.

9b (far right). Illustration of “White Herons.” Woodblock prints. Huang Fengchi, Xinxie liuyan tangshi huapu, in Tangshi huapu, bazhong, vol.2, 7b, 1620 edition, Hong Kong Chinese University library collection.

When the artisans appropriated two illustrated poems, “Snow Plums” (Xuemei, Figs. 8a-b) and “White Herons” (Bailu, Figs. 9a-b) from A Collection of Pictures to Illustrate Tang Poetry, they preserved the names of the two poets, the early Tang (618-712) poet Wei Yuandan and the mid Tang (766-835) poet Zhang Wei, respectively, but removed the title of each poem and the names of the calligraphers, He Zhiyuan (fl. 17th century) and Shen Dingxin (1573-1670). During the process of transcribing the original texts from a printed book to stone slabs, the artisans altered the original text and features of some of the characters. For instance, in the poem “White Herons,” the phrase qingyun or “clouds in clear sky” is changed to qingxue or “clear sky after snow.” The modification of one character breaks the rhyme principle, but introduces a season and weather condition, namely the snowy winter, that is represented on both hanging scrolls.[43] Li Tianpei’s epitaph records that he passed away on the eighth day of the first lunar month in 1875.[44] The snow scenes likely commemorate the particular time associated with his departure from this world and simultaneous arrival in the other world, eternal paradise. As I have pointed out above, the landscape imagery in this tomb should be understood as a funerary landscape painting, a less studied subject. The rules and principles of adjustment still need further investigation.

Moreover, by comparing the illustrations from A Collection of Pictures to Illustrate Tang Poetry, we see that the artisans made multiple alterations to situate the images to the physical space of the tomb (Figs. 10, 11). They flipped the illustration of “Snow Plums,” so the figure faces the entrance of the main chamber and also faces the figure in the scroll across the entrance as well; by adding foreground rocks and the remote mountains and water to the background, they extended the pictorial frame from a folio to a vertical hanging scroll. The original close-up of the figure in the illustration is pushed into the distance in the scroll’s middle ground.[45]

10 (left). “Snow Plums,” interior door frame of Li Tianpei and his wives’ middle chamber, 153 x 49 cm, limestone, constructed between 1870-1875. Photo courtesy of Li Haoxun.

11 (right). “White Herons,” left side of interior door frame of Li Tianpei and his wives’ middle chamber, 153 x 49 cm, limestone, constructed between 1870-1875. Photo courtesy of Li Haoxun.

More importantly, the artisans, likely in consultation with the patron, innovatively moved and added elements to transform the images from poetic descriptions of serenity and the beauty of nature to an elevation of the tomb occupant’s virtuous, ancestral and transformative status. On the “Snow Plums” scroll (Fig. 10) the original half-length scholar crouched inside a thatched pavilion is changed into a full-length elderly man sitting on the balcony of a pillar-and-beam structure braced with balustrades. The skeletal tree next to the seated figure in the print is replaced with a gigantic pine tree overshadowing the figure. The motif of a massive overhanging pine tree, a structure with a railed balcony, a gentleman and perhaps a servant boy behind him, was created by the well-known painter Ma Yuan (1160-1225) from the Southern Song period. This had become the exemplary image of an eminent gentleman by late imperial times.[46] By pairing a pine tree, a symbol of longevity, with a plum tree, a sign of purity, the stone painting generates another layer of meaning: It eulogizes the tomb occupant metaphorically as a person whose rightness would live forever.[47]

The other painting in this pair, “White Herons,” underwent much more modification (Fig. 11). In the original illustration (Fig. 9), the gentleman sits on a riverbank and watches white herons flying past. In the tomb image, the gentleman is positioned inside a pavilion nestled in a mountain fastness. The coiled rock formation around the pavilion suggests that it extends back into a natural void-like entrance to a grotto-heaven, the Daoist paradise hidden in the mountain’s cavernous interior.[48] Residing outside the entrance to a grotto-heaven was part of the cultivation one needed to attain immortal life.[49] There are certain discrepancies between the iconographic details of the standard cave-heaven and the mysterious pavilion represented in the “White Herons”; however, the designer and artisans seem to have agreed on using a hybrid pictorial form as an effective way to accommodate multiple landscape conventions.

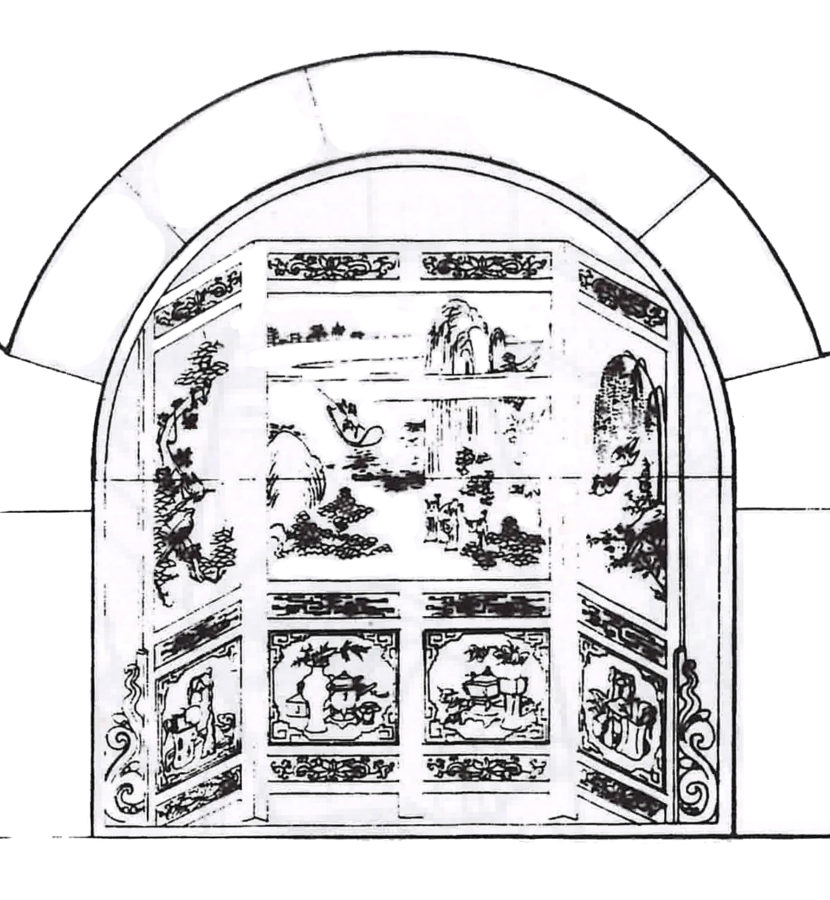

12a (left). Exterior of South Chamber, Li Tianpei and his wives’ middle chamber, limestone, constructed between 1870-1875. Photo courtesy of Li Haoxun.

12b (right). Line drawing of the room partition, horizontal hanging scroll above the entrance of the South Chamber, and the screen inside of the South Chamber, Li Tianpei and his wives’ tomb. After Shaanxi sheng kaogu suo, Dali lishi jiazu mudi (Xi’an: Sanqin chubanshe, 2003), 49, pl. 46.

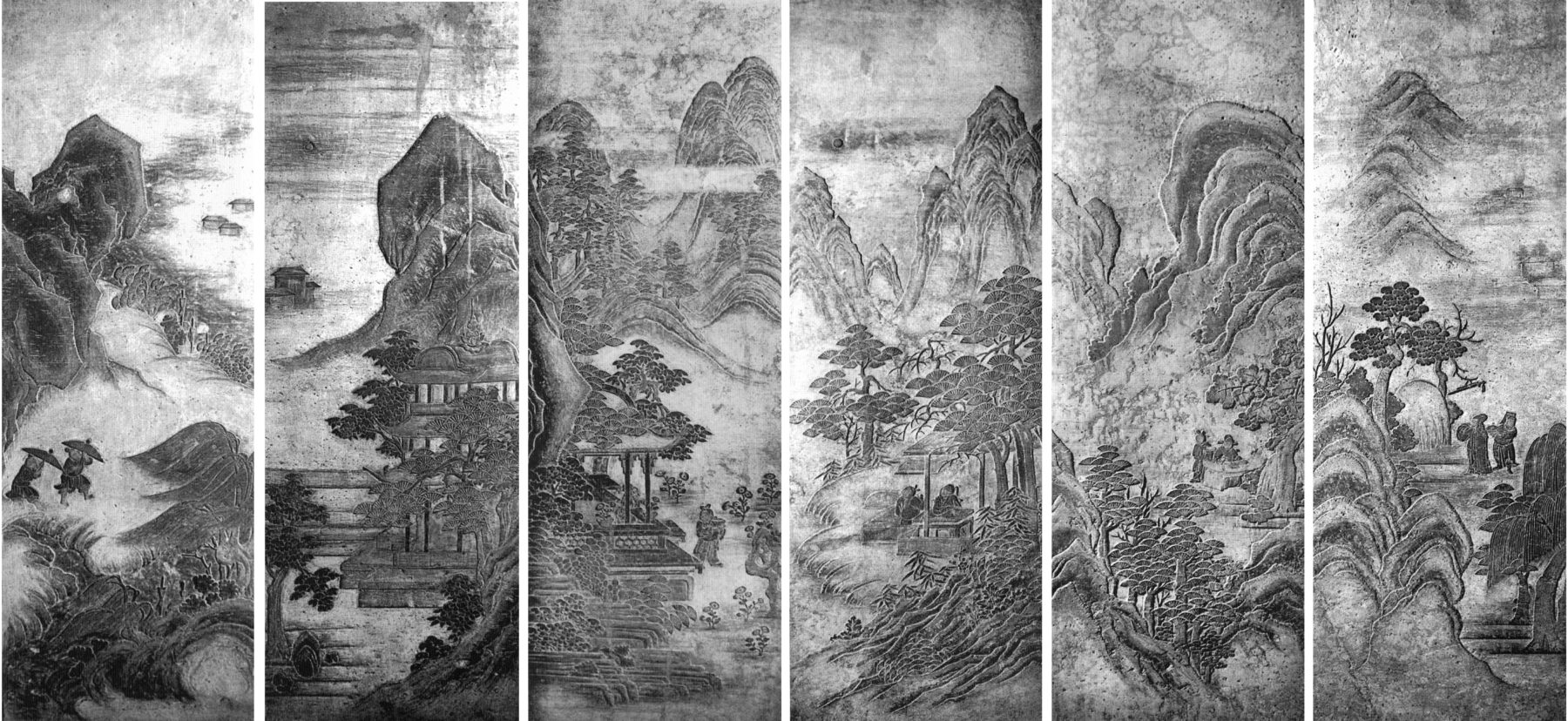

From Painted Screen to Stone | Mountain Life Images for the Male Deceased

The life in deep mountains is indicated figuratively through the landscapes on the room partitions and images carved in folding-screen format in each side chamber (Figs. 12a-b). The total of sixteen individual panels of landscape (not including other subjects) comprise an assemblage of a four-seasons landscape and the pictures of diangu or classic precedents, that is, the cultivated activities of famous literati that include growing chrysanthemums and lotus flowers, picking plum flowers, fishing, raising ducks, observing cranes and geese, playing the qin zither, contemplating on the moon, drinking wine, and composing poems (Fig. 13).[50] Here historical personalities are treated as cultural icons, and their amusements in the natural world, whether farming or artistic creation, are idealized as life in reclusion. Shi Shou-Chien reminds us that this combination of four-season landscapes and images of classical precedents emerged in the Ming period and was intimately related to the propagandistic purposes of court painting. Images of noble scholars and the common people’s regular mountain life at this time represented a peaceful and prosperous empire.[51] Since then, some classic precedents, often captioned with four-character aphorisms, have appeared as set images not only in painting, but also on various decorative arts such as New Year prints, ceramics, lacquer ware, wooden furniture, architectural decoration, and embroidery. Unlike the two pairs of hanging scroll images—the first pair illustrating the couplet at the tomb’s entrance and the second pair that copy illustrations of Tang poetry—the sixteen panels of classical precedents reflect another literary and pictorial convention, namely narratives of life in reclusion.

13a. Six-panel landscape screen, Li Tianpei and his wives’ south chamber, limestone, constructed between 1870-1875. Reconstruction of the photos after Shaanxi sheng kaogu suo, Qingdai mushi shike yishu (Xi’an: Sanqin chubanshe, 2008), 12-17.

Where the artisans altered the minute details of the hanging scroll images to indicate a posthumous status, no similar adjustments are observed on the two screens. Instead, the tomb designer converted the screens from worldly to posthumous objects through the convention of classical precedent. A unique historical narrative commemorating the dead unfolds from the first panel on the screen in the south chamber, read from the far right of Figure 13.

The screen begins on a memorial note. The referenced story is paraphrased as “Ji Zha guajian” (Youngest son Zha hangs up his sword) (Fig. 13a). Zha was a son of the King of Wu and also a politician of the Wu Kingdom during the Spring and Autumn period (771-476 BC). He met with the King of Xu on a diplomatic mission. The king showed great interest in Zha’s sword but did not say a word. Zha noted his interest, but could not very well give away his sword during the mission. He promised himself that he would present the sword to the king after he had accomplished his task. Sadly, when he returned to the Kingdom of Xu, the king had passed away. Zha went to the king’s burial site and hung his sword on a tree branch in front of the grave. The core value of this classical reference is the importance of keeping one’s promise to a friend, even if the friend no longer lives in this world. In late imperial China, this story had become one of a collection of commemorative celebrations for worthy men and was even included in an encyclopedia.[52] Hence, the tomb designer, working within the literary and pictorial canon of classical knowledge, inserted a memorial dimension onto the screen.

13b. Six-panel landscape screen (detail of “Youngest son Zha hangs up his sword”), Li Tianpei and his wives’ south chamber, limestone, constructed between 1870-1875. Photo courtesy of Li Haoxun.

The two six-panel screens also seem to mimic a type of screen that combined imitations of different artists from the same lineage.[53] This form emerged after Dong Qichang’s promotion of amateur painters. His followers copied the compositional schemes and brush idioms from historical artists in the same lineage and assembled the copies in a single album and later in a big-screen format where the different archaic styles were displayed in one frame. Such imitations are not precise copies of previous artists’ works, but rather demonstrations of how their compositions and brush styles were perceived by artists from the early Qing period.[54] It is important to stress that Dong Qichang’s followers were primarily concerned with generic scholarly activities such as watching waterfalls, traveling, and boating, rather than with concrete everyday-life activities in the mountains associated with particular historical figures. The fashion of assembling and copying archaic styles took on another material turn when such items became a luxury good. In a luxury context, it was important to alternate the monochrome ink and colored panels and to combine assorted brush styles. For example, an anonymous ancestral portrait created in the late eighteenth century to early nineteenth century shows a couple in official robes seated before an extraordinary eight-panel screen that likely evokes artists in the lineage of the Southern School (Fig. 14). Such a landscape screen referencing artistic lineage became a popular background for posthumous ancestral portraiture, like the two screens in Li Tianpei’s tomb.

14. Unknown artist, Portrait of an Imperial Censor and His Wife, late 18th-early 19th century. Hanging scroll, ink and color on silk. 168.3 x 98.7cm. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Photo: public domain.

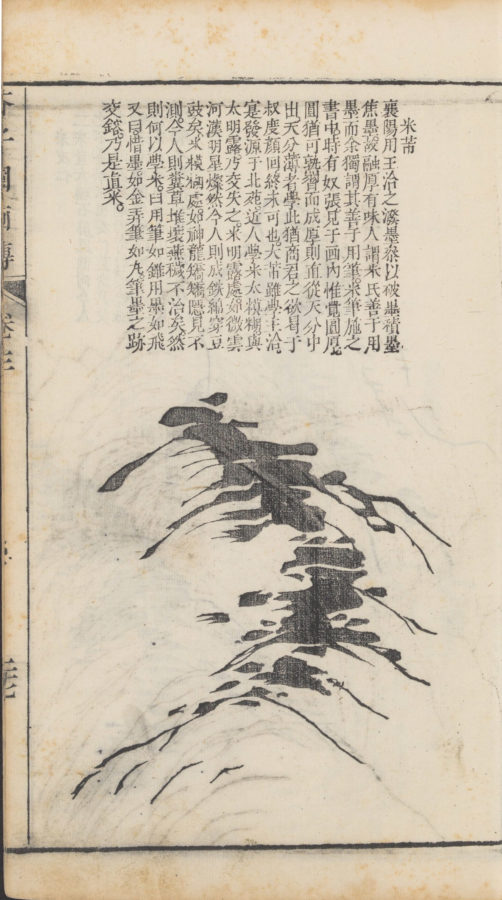

Lastly, the stone artisans who made Li Tianpei’s tomb clearly grasped the characteristics of such screens and reproduced representative historical brush idioms by use of composite methods. The conventional three-section composition of a landscape, foreground, middleground, and background, proved a convenient layout. Although further research of the precise pictorial models used for the carving needs to be conducted, it is likely that the artisans used a printed painting manual such as Painting Manual of the Mustard Seed Garden (Jieziyuan huazhuan) and other similar books as a source. Such painting manuals introduce images of rocks, trees, mountains, clouds, river, architecture, and human beings as modules that were considered essential to learning how to create a particular form.[55] The artisans used modules of mountains and rocks for the background and foreground of the screen panels. Many of the modules, especially mountain peak forms, are associated with historical artists. For instance Mi Fu’s (1051-1107) signature ink dot technique is explained in the section on mountain peaks and relevant text in the Painting Manual of the Mustard Seed Garden (Fig. 15). At the top of “Youngest son Zha hangs up his sword” (Fig. 13, right), the cluster of mountains is flipped from the woodblock print version during the process of transferring the image to stone. Other modules in the same image, such as rocks in the foreground, trees, and figures, do not necessarily conform with the Mi Fu style.

15. Illustration of Mi Fu style mountain. Woodblock. Wang Gai (1645-1710), ed., Painting Manual of the Mustard Seed Garden (Jieziyuan huazhuan), chuji, juan 3, 27a. Harvard Yenching Library collection.

Here, the imitation of the classic styles is incomplete, and the juxtaposition of classical fragments creates a new whole. The whole is indeed greater than the parts, but in this case, the new whole makes the fragments of different imagery point to a past painting that never existed, a reference which implies the production of the simulacrum itself as classic. In other words, the “reproduced” classic invokes a past that has never been and presents a copy without an original. Such a simulacrum has both social and technological possibilities: the artisan and the merchant-patron have together turned painting into ritual equipment, namely a screen for the dead. In other words, the simulacrum has concrete cultural effects; it mediates the transcendence of the deceased.

Exotic Landscape for the Ladies

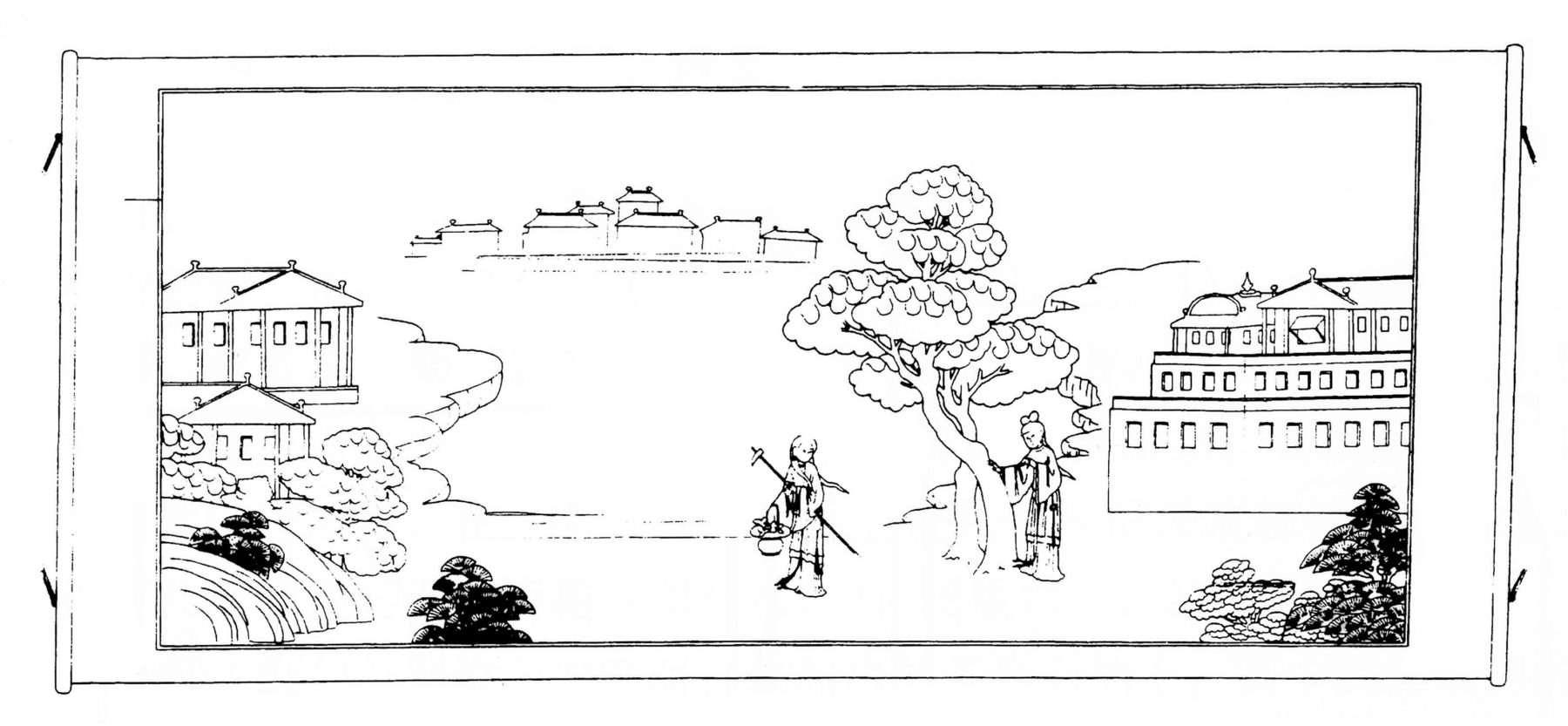

Chinese landscape painting was long institutionalized as a male-dominated practice. To this point, the imitation of classical landscape images in Li Tianpei’s tomb is very much reserved for the husband, but not for his four wives.[56] However, the tomb designers, perhaps includ-ing Li Tianpei’s fourth wife Madam Ge, attempted to create a feminine natural space outside the literati landscape tradition. A horizontal hanging scroll sits along the top of the door-frame to the south chamber, a peculiar position that does not echo any architectural and interior design tradition (Figs. 16a-b).[57]

16a (above). “A Lady Burying Flowers and a Lady under Catalpas.” Li Tianpei and his wives’ tomb, south chamber. Limestone. Constructed between 1870-1875. Photo courtesy of Li Haoxun.

16b (below). Line drawing of “A Lady Burying Flowers and a Lady under Catalpas,” after Shaanxi sheng kaogu suo, Dali lishi jiazu mudi (Xi’an: Sanqin chubanshe, 2003), 90, pl. 89.

Unlike the mountains and waters in literati landscape painting, here a man-made exotic garden is created through Western-style illusionism. An oblate-shaped lake dominates the center of the scroll, surrounded by winding shores. A bulky Western-style multistory building with rows of repetitive square windows sits on the right bank. Several similar structures in reduced scale appear on the left shore to suggest spatial recession. The distant buildings are chiseled in a cluster of silhouettes on a background to emphasize the limits of the horizon. The connection between the women and foreign architecture is further supported by two other hanging scrolls in another Li family tomb, which was only constructed for women.[58] Apparently, the depiction of foreign buildings and three-dimensionality were considered effective methods for constructing an exotic land as the women’s eternal paradise.

Two young ladies are positioned in the foreground of the horizontal scroll. They allude to two individual iconographies. The lady on the right stands behind two intertwined catalpas. Her right hand is placed on a curving tree trunk and the fingers of her left hand seem to gesture to the tree itself to accentuate its presence. There is a rich poetic tradition of the double catalpas as a symbol of a deeply bonded couple.[59] A catalpa was also a common plant used to decorate graveyards. That tradition might have originated with a long narrative poem, “A Peacock Southeast Flew (kongque dongnan fei),” written in the sixth century. In this poem, a Shaanxi couple deeply in love, Liu Lanzhi (the wife) and Jiao Zhongqing (the husband), were forced to divorce because Liu was disliked by her mother-in-law. Both of them were pushed to remarry, but they committed suicide just before Liu’s second wedding. Their families eventually decided to bury the bodies together and allow them to reunite in the other world. The trees planted on their burial site are specified in the poem. In Anne Birrell’s translation,

The two families asked for a joint burial,

A joint burial on the side of Mount Hua.

East and west were planted pine and cypress,

Left and right catalpa were set.

Branch with branch joins to form a canopy,

Leaf with leaf meets in wedlock.[60]

The intertwined branches and leaves would protect the couple’s eternal tie. Since then, catalpa and pine trees have been planted in graveyards to symbolize being eternally together. Here, a pine tree is also portrayed in the lower-right corner. Li Tianpei’s first three wives, the first principal wife, Madam Hu (posthumous name Chong Linü), second principal wife, Madam Li (posthumous name Ru Chunnü), and Madam Dan (posthumous name Yuan Huannü) all died before Li and likely before the tomb was constructed. The epitaph mentions that his three wives were reinterred with him the day Li Tianpei was entombed.[61] Madam Ge, Li’s fourth wife, might have had a role in the selection of the image.

The second figure, a lady setting out to bury flowers, is intimately related to Lin Daiyu, one of the principal protagonists in the romantic novel The Dream of the Red Chamber (Hongloumeng), written by Cao Xueqin (1715 or 1724-1763 or 1764) in the eighteenth century. In chapters 23 and 27, Daiyu, a most talented and ill-fated poet full of melancholy at the ephemerality of nature, often wraps the newly fallen flowers in an embroidered silk bag and buries the bagged flowers to preserve their purity.[62] In the wake of the novel’s popularity, the figure of a lady with a hoe and basket was canonized as a new form of beauty. When this iconography was appropriated to a burial context, the burying of flowers allegorically mirrors the burying of women. When the flowers in the basket are switched from the usual peach blossoms to the Buddhist symbol of lotus flowers, transcendence is explicitly indicated. Ellen Widmer’s research has shown that The Dream of the Red Chamber attracted a large number of female readers during the nineteenth century, mostly women of the gentry who responded to the novel with poetic writings.[63] Li Tianpei’s wives’ literacy is never mentioned in the epitaph, but as the daughters of scholars who all passed the provincial exam or, like Madam Ge, the daughter of a sixth-rank civil official in the Department of Rites, they might well have been educated and able to explore the most popular novel of the time. Although this hypothesis can never be proved, it is still safe to argue that the poetic images of women in this scroll provide allegories and visual idioms specific to a woman’s natural space, a space emphasizing emotional affects.

This horizontal scroll demonstrates how gender could mediate and interrupt the classics. As Wu Hung points out, the combination of western illusionistic space and beautiful-women figures provided a new language to convey women’s psychological moods at the Qing court of the eighteenth century.[64] By the nineteenth century, the new form had been popularized and even assimilated into tomb decoration. This allowed a hybrid configuration of themes from romantic literary writings and illusionistic depictions of landscape. Gender made this hybrid structure necessary because the female perspective did not exist in dominant classical literati painting. The new formation pushes the classical visual and literary forms into a new space that is now appropriate for a gendered gaze.

Picturing the Immortal Realm | Climbing the Mountain and Sailing to the Immortal Island

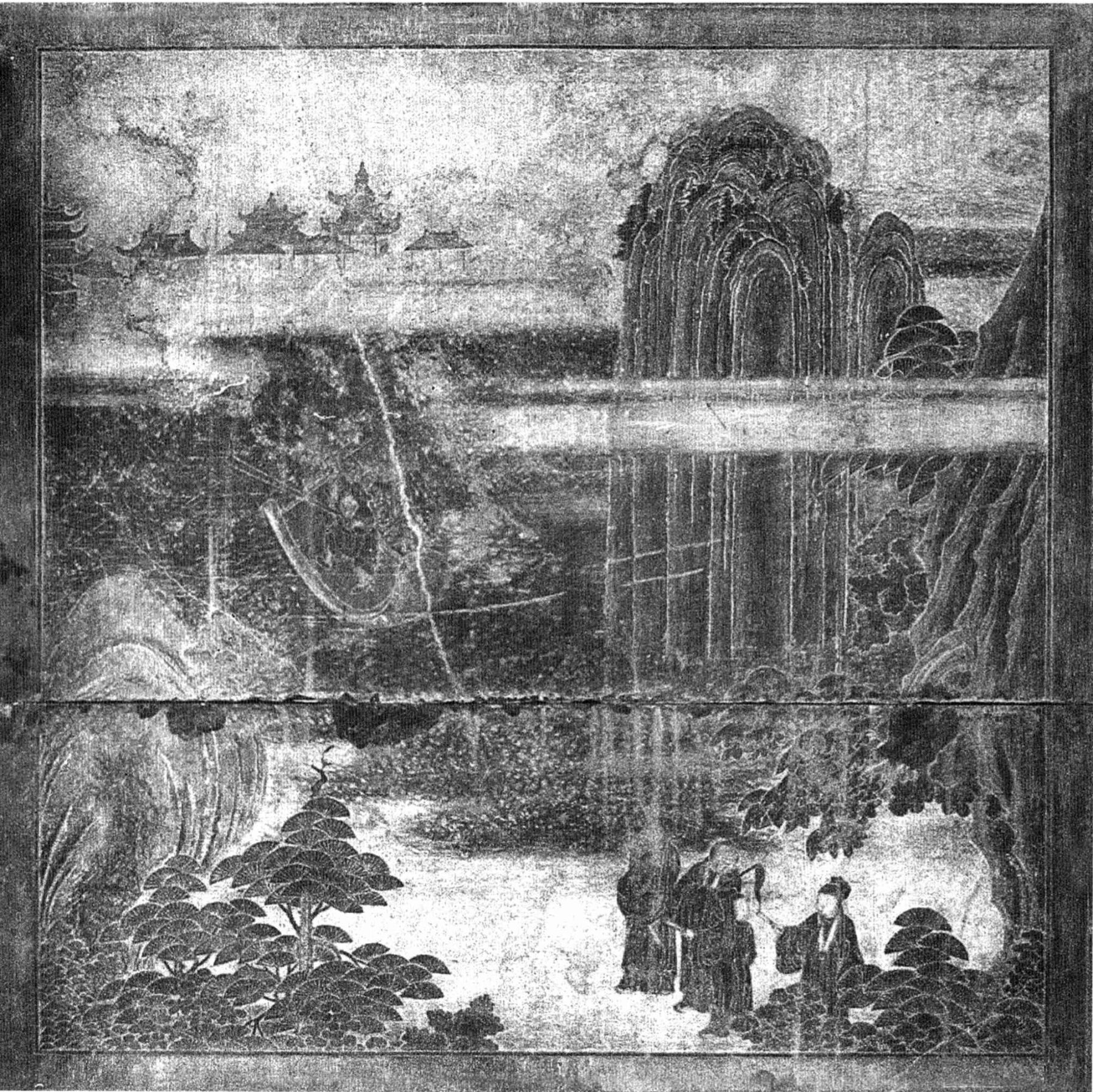

The last landscape appears on the back wall of Li Tianpei’s burial chamber (Fig. 17). The central image is a representation of a wooden framed screen whose square landscape serves as the visual aid for the journey from the inhabited mountain to immortal palaces and mountains (Fig. 18-a). The altitude of the location is suggested by the unusual arrangement in the foreground. The tops of pine trees and a nearby pinnacle rise in the left corner of the frame. This configuration also suggests that the height of the image’s setting is elevated metaphorically from the main chamber to the back chamber.

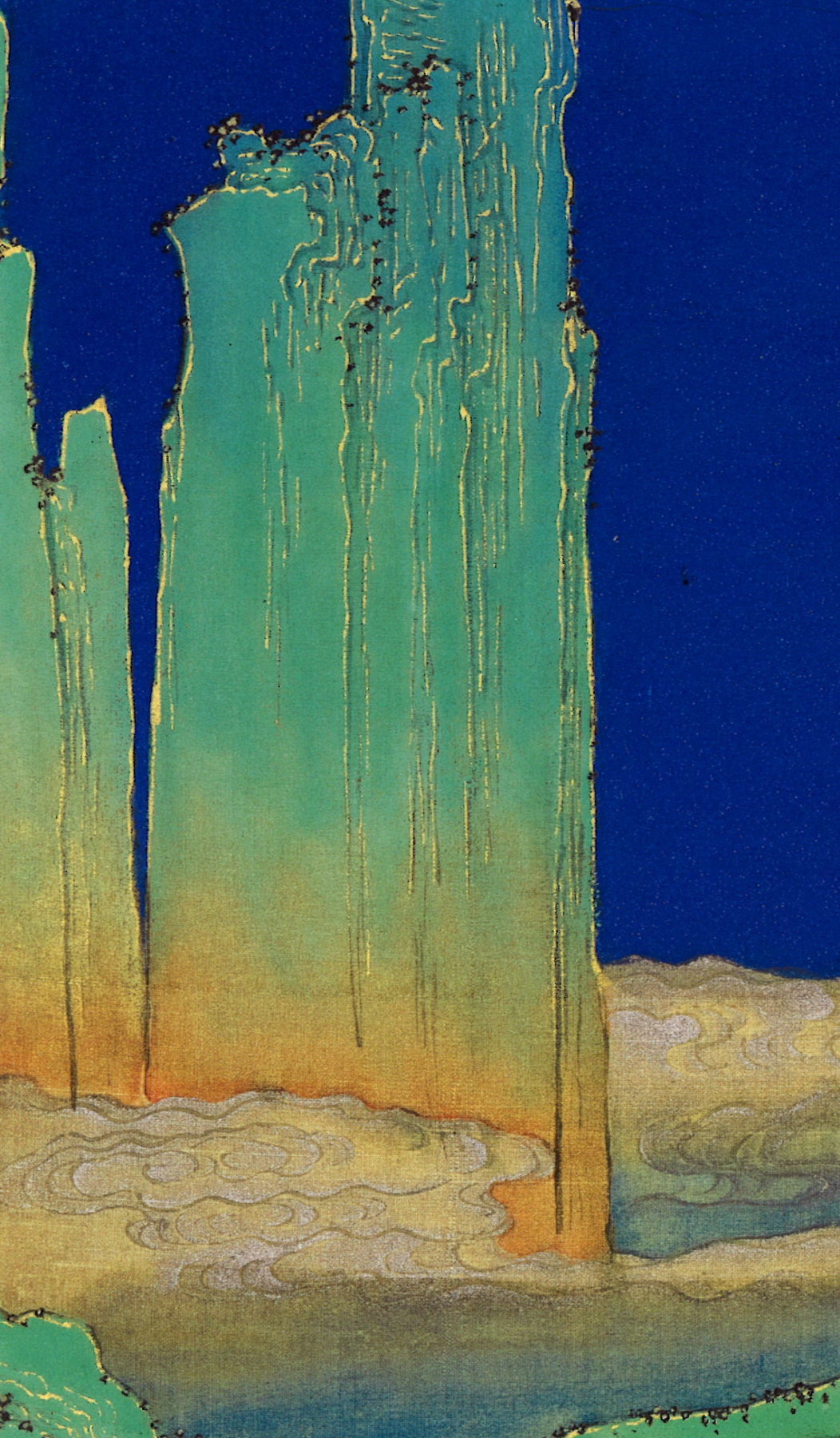

18a. “Immortals Lead the Way,” relief carvings on the back wall of Li Tianpei’s burial chamber. Limestone. Constructed between 1870-1875. Photograph from Shaanxi sheng kaogu suo, Qingdai mushi shike yishu (Xi’an: Sanqin chubanshe, 2008), 3.

18b. “Immortals Lead the Way,” (detail), relief carvings on the back wall of Li Tianpei’s burial chamber. Limestone. Constructed between 1870-1875. Photo courtesy of Li Haoxun.

Four figures are positioned in the lower right corner waiting for the boatman who is paddling toward them from the middle of an empty sea area in the middleground. Buddhist and Daoist priests are conversing with a male scholar on the far right. Wearing a long Daoist robe, the scholar follows the immortal’s hand by pointing his folded fan in the same direction. It is clear that the subject of this image is “Immortals Guiding the Way,” a motif of great popularity in the late imperial China. A soaring mountain, as in this landscape, often dominates the pictorial space. The verticality of the mountain indicates the sublime environment of sacred space. At the top of the image, several ornamented roofs suggest that here are the immortal palaces, the final destiny of the tomb’s occupant.

Intriguingly, the scholar’s lower body and left sleeve are obscured by catalpa and pine tree branches, which are arranged along the lower edge of the frame. If we speculate about the position of the scholar’s feet according to his body proportion, his feet should have been arranged on the frame. Such a peculiar treatment suggests a visual logic between the gentleman and coffin that would have been placed in front of the screen. The distance between lower edges of the frame and the floor of the burial chamber is about 50 centimeters, about the same height as the head end of a coffin. The excavation report indicates that the head ends of all coffins in Li Tianpei’s tomb face west wall.[65] It means that the head of Li Tianpei’s corpse would line up with the notional feet of the figure on the frame. In the long established Chinese funeral practice, the soul is often believed to come out from the top of human head or the acupuncture point of hundred convergence (baihui xue).[66] Hence, the route of the soul to the immortal land is materially linked.

As I mentioned at the beginning of this essay, the itinerary completed here is explicitly explained on the couplet outside the chambers. Now we can read the couplet in a more complete manner: “This place is connected to Penglai; he is so knowledgeable that he can transmit the classics to construct a stone chamber. His name is registered in the ledgers of immortals; he is so talented that he can compose fu (a rhapsody)to eulogize the Great Overarching Heaven.”[67] The stone chamber, which can be a library, a tomb, or a sacred cave, is a channel to Penglai, the legendary immortal island. The second line explains that the tomb occupant has had secured a place in the realms of the immortals. The last landscape provides a material safeguard by which the tomb occupant’s soul may pass from the physical domain to enter the image and follow the guidance of the immortals to eternal happiness. This same visual logic was duplicated in the two women’s chambers, not through landscape conventions, but rather using formulaic patterns of immortal palaces and mountains.

Artisanal Labor and Classical Reconfigurations

Complicated stone carvings like the landscapes in Li Tianpei’s tomb required a complex process to transform the designs into finely executed bas-reliefs. That process used four preliminary techniques: 1) creating a pattern (qi puzi)—drawing an outline of the composition in ink on thick paper; 2) pricking a pattern (zha puzi)—using a needle to pierce holes along the outlines; 3) pounding the pattern (pai puzi)—affixing the paper to the stone, then using a cotton pad coated with red mud powder to pound along the pattern; 4) transferring the pattern (guo puzi)—using ink to draw the pattern according to the pounded pattern, then using a stoneworking punch to carve the outline.[68] Next the carver begins the process of converting a two-dimensional outline into a three dimensional relief. This procedure—starting from the outline to sculpting the rough shapes of the image, then moving to the details—allows artisans to follow an overall compositional scheme and then make changes with small elements, such as figures and architecture. In other words, the work methods of stone carving provide the technological conditions in which artisans can creatively alter minute details and convert a landscape for the living into a landscape for the dead.

19 (left). “Entering the Mountains,” detail of a broken part of the carving demonstrating limestone structure, right hanging scroll on the façade of the entrance of Li Tianpei and his wives’ main tomb chamber. Limestone. 145 x 49 cm. Constructed between 1870-1875. Photo by the author.

20 (right). “Entering A Temple,” detail of ink wash effect, left hanging scroll on the façade of the entrance of Li Tianpei and his wives’ main tomb chamber, limestone, 145 x 49 cm. Limestone. Constructed between 1870-1875. Photo by the author.

However, another important question is how artisans reproduced different brush marks on stone. Indeed, on every landscape image in Li Tianpei’s tomb, the artisans took on the material translation of brush techniques used on paper and silk into stone by using various sculpting techniques; this process may also mediated by reference to prints and perhaps other media as well. Limestone is a relatively soft stone that can hold the subtle treatment of details. A broken part on the “Entering the Mountains” demonstrates the irregularity of entangled inner grey layers and white layers of limestone. (Fig. 19). Artisans’ familiarity with innate grain orientation and structure of the stone is crucial. To achieve the effects of the gradation of ink wash on the hanging scroll “Entering A Temple,” the artisans polished into the white sediment further down and left the darker sediment mostly alone (Fig. 20). Darker gray signifies ink effects, and white areas may represent paper, silk, or sometimes snow. In other words, to imitate the materiality of ink painting, the working process with stone is opposite, taking away surface, where with paper, ink is added. Although we see high-level stone carving techniques used in stone steles, jade, inkstone, and other fine stones in the Qing period, reproducing pictorial effects of brush techniques, ink wash and monochromic ink color is unique. It requires a high level of skill, but also a good understanding of ink painting techniques.

21. Unknown artist, An Qisheng Encounters Immortals (detail), Qing dynasty. Ink and color on silk. 59.6 x 40.4cm. Palace Museum, Taipei. Image from: Guoli gugong bowuyuan, ed., Hechu shi penglai: xianshantu tezhan (Taipei: Guoli gugong bowuyuan, 2018), 155.

The artisans not only reproduced ink wash effects, but also tried to evoke a colored painting through carving. The artistic intention of the last landscape suggests that the artisans tried to mimic a larger category of paintings in Chinese art, namely, pictures of immortal mountains (xianshan tu) and pictures of encountering immortals (yuxian tu).[69] The most common technique used in this category of work is called gongbi or meticulous painting style. As a detail from the painting “An Qisheng Encounters an Immortal” demonstrates, depictions of immortal mountains have several generic characteristics, such as mineral pigments of azurite blue and malachite green, rigid outlines and a well-defined contrast between different colors (Fig. 21). During the stage of final touches, the artist often adds a line in gold color on top of ink outlines to highlight the curves of the cliffs and to contrast the shimmery outlines with blue and green colors and the indigo blue background. To approximate this painting technique, the stone carvers used hammers and chisels to exploit the contrast of dark gray and white crystal in the rock. The effects of gold lines are vividly reproduced by the chiseled lines in lighter gray color (Fig. 18-b).

A detail showing the imitation of the axe-cut brush idiom from “Entering A Temple” provides a third example by which we can understand the technological translation of two-dimensional brushwork to three-dimensional relief (Fig. 22). The original term “axe-cut” for a type of brush stroke refers to the visual effect of split wood. The natural grain revealed by cutting with an ax was borrowed by artists from the Song period to depict the weathered structure of rock. This classic brush idiom is usually executed in a side stroke with a speedy brush movement, so a stroke with both wet and dry ink is produced. This process aestheticizes a three-dimensional natural rock to a two-dimensional brush mark by imitation of a natural property of wood. When the artisan reproduced this brush idiom in stone, he creatively translated the two-dimensional visual vocabulary back into three-dimensional form. Working with the grain of the stone, artisans first used a tool with a flat beveled blade and a hammer to chisel the flat surface into sections of different sizes and angles to imitate the sideway strokes and then used a punch to cut a longer line to indicate the extension of strokes.[70] Like a painter who knows the absorbency of his paper, the amount of ink and water in his brush, the stone carvers also knew the limestone’s composition and the possible visual effect associated with each of his various sculpting tools.[71] Through such a complicated technical and creative process, the artisans could reproduce various idiomatic brushstrokes associated with different painting techniques from both freehand ink-wash and meticulous brush paintings. Moreover, as Ko insightfully points out, in the early Qing period, inkstone artisans such as Wang Xiujun, took advantage of the stone medium and developed new techniques to represent landscape in naturalistic ways. Their wayaking use of the “stoneness” of the stone is different from painter’s creation of rocks on paper.[72] The artisans of the Li Tianpei’s tomb used a similar method to create the stoneness of the rocks and created a naturalistic visual effect.

22. “Entering A Temple,” detail of the axe-cut brush technique, left hanging scroll on the façade of the entrance of Li Tianpei and his wives’ main tomb chamber. Limestone. 145 x 49 cm. Constructed between 1870-1875. Photo courtesy of Li Haoxun.

Here we see a dialectic of artisanal labor, time, and knowledge. The artisans perform labor that is qualitatively different from that of the painter of the classic landscape. These artisans may not have published theories about transposing classical precedents or landscape motifs onto a different material but, as we have seen, they had numerous skills to do so. Their concern of “artistic lineage” is perhaps more related to artisanal linage of skills. Such skills enable artisans to have a concrete connection to the works by translating the images from one medium to another. This intermedial translation gave them a craft-based knowledge of the classical themes that was beyond simple representation. In other words, they knew the classics under the sign of erasure—outside the traditional literati context for the classics, they experienced the immediate materiality of the classics in a space where they were not explicitly contemplated.

Artisans were often commissioned by merchants; the merchant determined the form and content, and the artisan realized it through skill and labor. The time taken to complete this labor was significant. While it might take a few hours to reproduce a classic landscape in ink and wash, it took months for an artisan to sculpt a classical image. Although Qing China was not a capitalist society, even there, duration increased the value of the carved classic because it had more labor-time congealed within it.[73] Through all this, we see how objects that would have hybridized classical references are further transformed through being materially mediated (into a carved stone simulacrum) for a new audience, namely the dead. The source references are put into question here, and they persist primarily as form. Details associated with the living world are altered and yet the basic form remains, which is why we recognize it as landscape. We could say that “classics” are always formed retroactively—the work does not register as a classic until it is later recognized as such. What is classic in works like Li Tianpei’s tomb is not just its particular content, but a combination of form and skill. Even the transformation through form and skill must be rethought as we move from literati to artisanal labor.[74] The very immortality associated with the classic in the sphere of the literati is secured precisely by the knowledge of artisans outside that sphere.

Chinese Glossary:

An Qisheng 安期生

baihui xue 百會穴

Bailu 白鷺

Bayu 八魚

Bohai 渤海

diangu 典故

Cao Xueqin 曹雪芹

Chong Linü 崇立女

Chan 禪

chuanjing 傳經

Dali 大荔

Dan 淡

Dong Qichang 董其昌

fan 幡

fu 賦

Fuping 富平

Gansu 甘肅

Gaozu 高祖

Ge 葛

gongbi 工筆

guo puzi 過譜子

Han 漢

He Zhiyuan 何之元

Hongloumeng 紅樓夢

Hu 扈

Huang Fengchi 黃鳳池

Hui 回

Ji Zha guajian 季札掛劍

Jiao Zhongqing 焦仲卿

Jieziyuan huazhuan 芥子園畫傳

kongque dongnan fei 孔雀東南飛

Li 李

Li Daojian 李道堅

Li Jingfu 李景福

Li Tianpei 李天培

Liao 遼

Lin Daiyu 林黛玉

Liu Lanzhi 劉蘭芝

Liu Rushi 柳如是

Ma Yuan 馬遠

Mi Fu 米芾

Ming 明

Minghua 明畫/冥畫

mingqi 明器/冥器

Mo Shilong 莫是龍

pai puzi 拍譜子

Penglai 蓬萊

qi puzi 起譜子

Qing 清

qingyun 晴雲

qingxue 晴雪

Ru Chunnü 汝椿女

Shaanxi 陝西

shanshui 山水

shanshui hua 山水畫

Shen Dingxin 沈鼎新

shishi 石室

Song 宋

Tang 唐

Tangshi huapu 唐詩畫譜

Tongzoufu 同州府

Wang Xiujun 王岫君

wen 文

Wei Yuandan 韦元旦

Wu 吳

xianshan tu 仙山圖

Xinjiang 新疆

Xu 徐

Xuemei 雪梅

Yemaotai 葉茂台

Yingzhou 瀛洲

Yuan 元

Yuan Huannü 元煥女

yuxian tu 遇仙圖

Zha 札

Zhang Wei 張謂

zha puzi 扎譜子

zhuang 幢

zishi 子史

Zishi jinghua 子史精華

I am very grateful for Wu Hung’s inspiration in initiating this project and to Dorothy Ko, Jennifer Nelson, Terre Fisher and an anonymous reviewer for their generous feedback on an early version of this article. I want to thank Wang Ji for his unparalleled work as a research assistant and Li Haoxun and Li Jinhang for taking photographs and arranging travel logistics for me during my visit to the Li family tombs. I also want to acknowledge the colleagues from the Classical Chinese Reading Group that was led by Ann Waltner and Rivi Handler-Spitz. Everyone from this group provided input that helped me to craft my translation of classical poems. This project was nourished through conversations with friends and colleagues. I would like to thank Daniel Greenberg, He Xilin, Li Qingquan, Viren Murthy, Julia Orell, Kathleen Ryor, Catherine Stuer, Tao Jin, Peggy Wang and Wang Yudong.

- [1] About sixteen tombs were discovered in an archeological survey on the Li family cemetery. Eleven are stone-chambered, three are bricks-chambered and two are earth-chambered tombs. Shaanxi sheng kaogu suo, Dali lishi jiazu mudi (Xi’an: Sanqin chubanshe, 2003), 2-4.

- [2] “地接蓬萊學可傳經築石室,” in Shaanxi sheng kaogu suo, Dali lishi jiazu mudi, 95.

- [3] In the discussion of Suzhou’s renowned scholar-official Wen family from the mid-to-late Ming period, Craig Clunas has shown some overlapping issues concerning tombs and social status in the context of the literati family. He has enlightened us about how tomb lands along with gardens, ancestor shrines, and dwellings were conceived as both cultural and monetary properties. The number of graves and size of the graveyard were considered elements in the public landscape and are important criteria to identify a family’s prominence. See Craig Clunas, Fruitful Sites: Garden Culture in Ming Dynasty China (Durham: Duke University Press, 1996), 130-132.

- [4] For the discussion of the concept of spiritual painting, please see Li Qingquan’s study of two hanging scrolls found in the Yemaotai tomb from the Liao dynasty. See Li Qingquan, “Muzang zhong de huiqitu.” Yishushi Yanjiu, vol. 5 (2003): 371-398.

- [5] For an in-depth discussion on mingqi or spiritual articles, see Wu Hung, The Art of the Yellow Springs: Understanding Chinese Tombs (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2010), 87-99.

- [6] Wu Hung, The Art of the Yellow Springs, 117.

- [7] Wu Hung, “Simulated Landscape Paintings: Newly Unearthed Tomb Murals in Tang China,” Art Bulletin, vol. 103, no. 3 (December 2021), 24.

- [8] The lineage tradition does not mean that artists over a span of a thousand years did not have interest in new forms and subjects, but rather it was an important characteristic of canon formation in China. Jerome Silbergeld, “Changing Views of Change: The Song-Yuan Transition in Chinese Painting Histories,” in Vishakha N. Desai, ed., Asian Art History in the Twenty-First Century (Williamstown, MA: Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, 2007), 40-67.

- [9] Sherman E. Lee, Chinese Landscape Painting (Cleveland: Cleveland Museum of Art 1954).

- [10] James Cahill, The Distant Mountains: Chinese Painting of the Late Ming Dynasty, 1570-1644 (New York and Tokyo: John Weatherhill, Inc. 1982), 9-10.

- [11] For a discussion on how an artist adopted different models within one painting, see Julia Orell, “Itinerary and Painting Lineage: Ten Thousand Miles along the Yangzi River in Seventeenth-Century China,” in Karin Gludovatz, Joachim Rees and Juliane Noth, eds., The Itineraries of Art: Topographies of Artistic Mobility in Europe and Asia (Leiden: Brill, 2015), 153-173.

- [12] Michael J. Hatch, “Epigraphic and Art Historical Responses to Presenting the Tripod, by Wang Xuehao (1803),” Metropolitan Museum Journal 54 (2019), 102, f.18. For a discussion of painting practices in nineteenth century China, please see Claudia Brown, Transcending Turmoil: Painting at the Close of China’s Empire, 1796-1911 (Phoenix, Arizona: Phoenix Art Museum, 1992). The less studied battle paintings produced by the court artists in the nineteenth century reveal a new pictorial form that combines older “amateur” style landscape, representations of different city-walls and figures. The court artists created more than sixty paintings to commemorate Manchu military success in handling various rebellions in the late Qing period. These painters directly copied the brush idioms associated with master landscapists from Yuan and Ming periods, superimposing archaic mountains and rivers on these paintings. Zhang Hongxing, “Studies in Late Qing Dynasty Battle Paintings,” Artibus Asiae, vol.6, no. 2 (2000), 265-296.

- [13] For instance, see Zheng Yan, “Han Xiu mu bihua shanshui tu zouyi,” Gugong bowuyuan yuankan 5 (2015), 87-109.

- [14] The epigraph that contains the biographical information of Li Tianpei and his three wives Madam Hu, Madam Li and Madam Dan was transcribed by the archeologists of the Li family tombs. Shaanxi sheng kaogu suo, Dali lishi jiazu mudi, 102-105.

- [15] Han Kang, “Dali qingdai lishi jiazu huaxiangshi mu chutan,” Central Academy of Fine Arts, M.A. thesis, 2007, 5-7.

- [16] Shaanxi sheng kaogu suo, Dali lishi jiazu mudi, 104.

- [17] In Li Tianpei’s tomb epitaph, “zishi” is used to describe the type of texts he enjoyed in intellectual conversation. Zishi is used here as a loose term to refer to comprehensive knowledge of histories and ancient masters’ thoughts and writings. Since Li Tianpei never took the imperial exams, the writer of his epitaph did not mention Confucian classics at all; instead, he just used the word zishi. The choice of this word might be intended to avoid the embarrassment that Li never took official exams, in which Confucian classics are a major component. During the Kangxi period, a compilation entitled Essence of the Masters and Histories (Zishi jinghua) was completed and was published in 1727. For the content of such massive compilations, please read Benjamin Elman, On Their Own Terms: Science in China, 1550-1900 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2005), 237. I am also grateful for Wang Ji’s comment on this phrase.

- [18] Shaanxi sheng kaogu suo, Dali lishi jiazu mudi, 105.

- [19] Cynthia Brokaw, The Ledgers of Merit and Demerit: Social Change and Moral Order in Late Imperial China (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1991), 30.

- [20] Hanyu dacidian bianji weiyuanhui and Hanyu dacidian biancuanchu eds., Hanyu da cidian, vol. 7 (Shanghai: Hanyu dacidian chubanshe, 1991), 988-989. For a more in-depth discussion of the stone chamber in Daoist discourse, see Shih-shan Susan Huang, Picturing the True Form: Daoist Visual Culture in Traditional China (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2012), 116-117.

- [21] “名登仙籍才堪作賦咏羅天,” in Shaanxi sheng kaogu suo, Dali lishi jiazu mudi, 95. For an overview of fu, see https://www.britannica.com/art/fu-Chinese-literature.

- [22] On the subject of the immortal islands in relation to the Daoist cosmos, see Shih-shan Susan Huang’s comprehensive discussion. Huang, Picturing the True Form, 105-106. This idea was already visualized in the Southern Song period: for example, a carving with the image of a man in a boat sailing to Penglai was excavated from a layperson’s tomb. Ibid, 113, Fig.2.21.

- [23] To understand how stone is used as a medium for literary inscription and its ideological and religious meanings, see Robert E. Harrist, The Landscape of Words: Stone Inscriptions from Early and Medieval China (Seattle: Washington University Press, 2008). While discussing the incised inscription on the surface of a wide range of objects, including stone utensils, Jonathan Hay calls our attention to an important issue of “literati inscriptionality” and “non-literati inscriptionality” associated with each object. Jonathan Hay, Sensuous Surfaces: The Decorative Object in Early Modern China (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2010), 205-213.

- [24] Dorothy Ko, The Social Life of Inkstones: Artisans and Scholars in Early Qing China (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2017), 190.

- [25] These two pairs of landscapes were respectively named “Discussing Dao in the Deep Mountains” and “An Ancient Temple in the Deep Mountains” by the archaeologists of the excavation report. However, these titles do not reflect the ritual context of these two hanging scrolls. Shanxisheng kaogu suo, Dali lishi jiazu mudi, 89. The door was originally sealed with a stone slab that was lost in the robberies of the tomb. The framing couplet imitates wooden couplets.

- [26] For a typical landscape of these three islands see Stephen Little and Shawn Eichman eds., Taoism and the Arts of China (Chicago: The Art Institute of Chicago in association with University of California Press, 2000), 370-371.

- [27] “翠栢蒼松一帯濃陰庇壽域, 青山緑水四圍秀氣繞佳城,” in Shanxisheng kaogu suo, Dali lishi jiazu mudi, 94, pl. 3.

- [28] Clunas, Fruitful Sites, 180. For a review of the scholarship on landscape and geomancy, see 183-184 in the same book.

- [29] Ibid, 178.

- [30] Huang Shih-Shan, “Xie zhenshan zhixing: cong ‘shanshui tu’, ‘shanshui hua’ tan daojiao shamshui guan zhi shijue xingsu,” Gugong xueshu jikan, vol. 31, no. 4 (2013), 121-204, specifically 148-149.

- [31] Han Kang has discussed the Li family tombs from the perspective of geomantic practice, but he mainly concentrates on the auspicious dates for constructing a tomb. He concludes that Li Tianpei’s tomb was probably constructed between 1870 to 1874. Han Kang, “Dali qingdai lishi jiazu huaxiangshi mu chutan,” 16-17.

- [32] A graveyard is an uncommon subject in the canon of Chinese landscape painting. Hui-shu Lee has discussed one rare example of a painting by the well-known woman painter Liu Rushi who included the graveyard of her parents-in-law in one of her site-specific paintings. Hui-Shu Lee, “Voices from the Crimson Clouds Library: Reading Liu Rushi’s (1618–1664) Misty Willows by Moonlit Dike,” Journal of Chinese Literature and Culture, vol. 2, no. 1 (April 2015), 173–206.

- [33] Roger Goepper, The Essence of Chinese Painting, translated by Michael Bullock (Boston: Boston Book and Art Shop, 1963), 173-174.

- [34] Li Xueqin, ed., Liji zhengyi, in Shisanjing zhushu (Beijing: Beijing daxue chubanshe, 1999), 1266.

- [35] As Susan Shih-shan Huang points out, “entering the mountains” is a ritual discourse in Daoist practice. Huang, Picturing the True Form, 115.