Contribution to the Theory of Ideology

"Beitrag zur Ideologienlehre," taken from: Theodor W. Adorno, Gesammelte Schriften in 20 Bänden - Band 8. Soziologische Schriften I. S. 457-477. © Suhrkamp Verlag Frankfurt am Main 1972. Alle Rechte bei und vorbehalten durch Suhrkamp Verlag Berlin.

The concept of ideology has commonly been adopted in academic parlance. “Only rarely,” Eduard Spranger recently wrote, “is there still discussion of political ideas and ideals; rather more often of political ideologies.”[1] With this concept intellectual forms are drawn into the dynamic of society by relating them to the contexts that motivated them. In this way the concept of ideology critically penetrates their immutable semblance of existing in themselves, as well as their claims to truth. In the name of ideology, the autonomy of intellectual products, indeed the very conditions under which they themselves become autonomous, is thought together with the real historical movement of society. These intellectual products originate within this movement, and they perform their functions within it, too. They may stand in the service of particular interests, whether intentionally or not. Indeed, their very isolation, through the constitution of an intellectual sphere and its transcendence, is, at the same time, identified as a social consequence of the division of labor. This transcendence already justifies a divided society simply by virtue of its form. Participation in the eternal world of ideas becomes the preserve only of those who are privileged through their exemption from physical labor. Motifs of this kind, which resonate everywhere that ideology is discussed, have a certain concept; sociology, which wields this concept, stands in opposition to traditional philosophy. Traditional philosophy still always makes the claim, even if not in precisely the same terms, that its work deals with enduring and unchangeable essences, as opposed to the transformation of appearances. The turn of phrase once used by a German philosopher (who still possesses a great deal of authority today) when, in the pre-fascist era, he compared sociology to a cat burglar, is well known.[2] Such ideas long ago seeped into popular consciousness and essentially contributed to a distrust of sociology. They require further reflection, because they amalgamate things that have for a long time been incongruous, and indeed some that are at times baldly contradictory. With the dynamization of the contents of the mind through the critique of ideology, one tends to forget that the theory of ideology is itself subject to this same historical movement; that, if not in substance, then nonetheless in function, the concept of ideology transforms through history, and the same dynamic governs this. What is called ideology—and what ideology is—can only be perceived insofar as one does justice to the movement of the concept; this movement is at the same time one of its objects.

Leaving aside those oppositional countercurrents within Greek philosophy that have fallen into disrepute thanks to the triumph of the Platonic-Aristotelian tradition, and which only today are being painstakingly reconstructed, the general conditions under which consciousness has false content have been noted at least as far back as the beginning of modern bourgeois society, at around the turn of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Francis Bacon’s anti-dogmatic manifestos for the liberation of reason declare a struggle against “idols”: those collective prejudices which weighed upon humanity in the final phase of an epoch just as they had at its beginning. His formulations occasionally sound like anticipations of thoughts belonging to that modern, positivist critique of language: semantics. He characterized a typical idol of which the mind had to rid itself, the idola fori, which can be loosely translated as the idol of mass society. “Men associate through talk; and words are chosen to suit the understanding of the common people. And thus a poor and unskillful code of words incredibly obstructs the understanding. […] Plainly words do violence to the understanding, and confuse everything.”[3] Two aspects of these sentences, which are drawn from the first phase of enlightenment in early modernity, deserve emphasis. Firstly, the deception is blamed on “the” people, as though they were invariable natural beings; it is not blamed on the conditions that make them this way, nor on those conditions that govern them as a mass. The doctrine of innate delusion, a piece of secularized theology, still appears even today in the arsenal of vulgar theories of ideology: insofar as false consciousness is considered as people’s fundamental state, or insofar as it is generally ascribed to their socialization, then not only are the concrete conditions of false consciousness ignored, but even more than this, the delusion is justified as a law of nature, so to speak. The domination of the deluded is founded precisely on this, just as Bacon’s student Hobbes later actually sought to justify. Furthermore, logical impurity is blamed on the deceptions of nomenclature. Therefore, the subject and its fallibility are blamed instead of objective historical constellations, just as Theodor Geiger recently disposed of ideologies as matters of “mentality,” denouncing their relation to the social structure as “pure mysticism.”[4] Bacon’s concept of ideology, if it is accepted that we can speak of such a thing, is already just as subjectivistic as views that are prevalent today. While his doctrine of idols sought to aid the emancipation of bourgeois consciousness from the church’s condescension, and therefore was aligned with the progressive tendency of this entire philosophy, the limitations of such a consciousness can already be foreseen in his work: the intellectual eternalization of relations, which are conceived of after the model of the antique body politic, which one emulates; and abstract subjectivism, which fails to anticipate the moment of untruth in the isolated category of the subject itself.

The politically progressive impulse that is found in Bacon’s sketch of a critique of false consciousness emerges much more sharply in the Enlightenment of the eighteenth century. The left-wing encyclopedists Helvétius and d’Holbach held that the kind of prejudices that Bacon said applied to humanity in general held a particular social function. These prejudices served to perpetuate unjust situations, opposing both the realization of happiness and the creation of a rational society. As Helvétius puts it, the prejudices of the great are the laws of the meek.[5] In another work he writes, “Experience shows us that nearly all questions of morality and politics are decided not by reason but by force. If opinions rule the world, then in the long run it is the powerful that rule opinions.”[6] The modern enterprise of public opinion research forgot this axiom, and believed right up to the most recent times that it could halt after surveying the broad range of subjective opinions at any given time, taking these views as the last given datum. This indicates how enlightenment motifs have changed their function as society has changed. What was once conceived critically now serves only to establish whatever “is the case,”[7] and consequently the findings bear only on themselves. Comments about the ideological surface, and therefore about the distribution of opinions, stand in for the analysis of their significance with regard to the whole of society. Admittedly, the encyclopedists also did not consistently attain insights into the objective origins of ideology or into the objectivity of its social function. Often, they still reduced prejudices and false consciousness to the machinations of the powerful. As d’Holbach put it, “Authority has generally held that the perpetuation of current opinions is in its interests; the prejudices and errors that it deems necessary in order to secure its power are perpetuated through power, which never conforms to reason.”[8] At around the same time, however, Helvétius—perhaps the greatest mind of all the encyclopedists—had already envisaged the objective necessity of what otherwise was ascribed to the evil of the Camarillas: “Our ideas are the necessary consequences of the societies in which we live.”[9]

The motif of necessity stands at the very center of the work of this French school, who named themselves idéologues—literally researchers into ideas. The word “ideology” arises from one of greatest exponents, Destutt de Tracy. He drew from empirical philosophy, which dissects the human intellect in order to lay bare the mechanism of knowledge, in order to reduce questions of truth and bindingness to this mechanism. Yet his aim was not epistemological, and nor was it formal. He did not want to seek out the conditions for which judgments of the mind were valid, but instead sought to observe those intellectual phenomena that constitute the content of consciousness itself, and to describe them like some natural object, a mineral or a plant. In a provocative formulation, he once called ideology an element of zoology. Following Condillac’s tangibly materialistic sensualism, he wanted to trace all ideas back to their origins in the senses. He was no longer satisfied with refuting false consciousness and indicting whatever cause it lent itself to. Instead, he thought that each consciousness, regardless of whether it was false or correct, should be brought before the laws that govern it. From there it would only be one step to comprehend the social necessity of all contents of consciousness in general. The idéologues shared the adoption of a mathematical or natural-scientific orientation with the older tradition, just as they do with the most recent positivism. Destutt de Tracy also placed development and training in linguistic expression in the foreground; indeed, he wanted to connect the verification of primary data with a mathematized grammar and language, in which each idea would map directly to a sign, in just way that Leibniz and earlier rationalism famously intended. However, all of this would now be rendered applicable for a practical political purpose. Through confrontations with what was given to the senses, Destutt de Tracy still hoped to prevent the establishment of false, abstract principles, as these damage not only communication between people but also the construction of society and the state. He anticipated that his science of ideas—ideology—would be able to demonstrate the same measure of certainty as physics or mathematics. The strict methodology of science should prepare to put an end, once and for all, to the arbitrariness and caprice of opinions, which had been the scourge of philosophy since Plato. False consciousness, which would later be called ideology, would finally dissolve when confronted by the scientific method. At the same time, though, he allotted a primacy to science and to the intellect. The school of the idéologues, whose thought drank not only from materialist but also from idealist sources, faithfully held to the belief, despite all empiricism, that consciousness determines existence. Destutt de Tracy considered this highest science to be a human one, which would provide the basis for the entirety of political and social life. Comte’s notion of the ruling role of sociology within the sciences, and ultimately in real social life, is therefore already virtually contained in the work of the idéologues.

Furthermore, the ideologues initially intended theirtheory to be progressive. Reason ought to rule in order to erect a world according to human preferences. Taking a liberal view, they presumed there would be a harmonious balance of social forces, insofar as each person acted on the basis of their own well-understood, transparent interests. The concept of ideology also operated in this way in real political struggles. According to a passage cited by Pareto, Napoleon already raised an accusation of subversion against the idéologues, albeit in a subtler way, despite his dictatorship having been tied in many ways to bourgeois emancipation. This accusation has accompanied the social analysis of consciousness like a shadow. In a language spoken in Rousseauvian tones, he emphasized those irrational moments which later were continually invoked against the so-called intellectualism of ideology critique. Meanwhile, however, Pareto merged the theory of ideology in its later phase with an extreme irrationalism. Napoleon’s sentences proclaim that:

All the misfortunes that our beautiful France has been experiencing have to be ascribed to ‘ideology,’ to that cloudy metaphysics which goes ingeniously seeking first causes and would ground the legislation of the peoples upon them instead of adapting laws to what we know of the human heart and to the lessons of history. Such errors could only lead to a regime by men of blood, and they have in fact done so. Who cajoled the people by thrusting upon it a sovereignty it was unable to exercise? Who destroyed the sacredness of the laws and respect for the laws by basing them not on the sacred principles of justice, on the nature of things and the nature of civic justice, but simply on the will of an assembly made up of individuals who are stranger to any knowledge of law whether civil, criminal, administrative, political, or military? When a man is called upon to reorganize a state, he must follow principles that are for ever in conflict. History draws the picture of the human heart. The advantages and disadvantages of different systems of legislation have to be sought in history.”[10]

However much these sentences might lack lucidity, and however much they fuse together the French Revolution’s doctrine of natural law with a later physiology of consciousness, this much is clear: that Napoleon sensed that positivity was endangered by every analysis of consciousness, and he felt that it would be better preserved by the heart. Furthermore, in Napoleon’s pronouncement the later linguistic usage of “ideology” appears, as he turned the phrase “unworldly ideologues” against the purportedly abstract utopians in the name of “realpolitik.” But what he had misjudged was that the analysis of consciousness offered by the idéologues was in no way incommensurate with interests in domination. They were already associated with a technical-manipulative moment. Positivist social theory has never renounced this moment, and has always kept its findings prepared for social aims that are opposed to each other. Furthermore, for the idéologues, knowledge about the origin and genesis of ideas was the domain of experts, and what these experts figure out should enable the legislature and leadership of states to bring about and maintain the desired order, which is then, however, equated with a rational order. Yet the idea nonetheless prevails that people can be led through some correct knowledge of a chemistry of ideas. In contrast, in the sense of skepticism, which inspired the school of idéologues, the question of the truth and the objective bindingness of ideas recedes. Along with it also goes the question of objective historical tendencies upon which society is based, both in its blind “naturally-lawful” course, and in its potential to become a conscious rational order.

In scientific socialism’s doctrine of ideology these moments are brought into agreement.[11] I will not address this doctrine, since its broad outlines are generally well known. On the other hand, the formulations on which it is founded require detailed interpretation, particularly the question it raises about the relationship between the social situation of the intellect to its inner consistency and autonomy. These formulations would have to be involved wherever the central questions of dialectical philosophy are taken up. The truism that ideologies rebound into social reality is not sufficient. The contradiction between the intellect’s objective truth and its mere being-for-another—a contradiction that traditional thinking cannot contend with—would have to be recognized as the matter at hand, and not merely an inadequacy of method. Since today I am concerned with the transformations in structure and changes in function of both ideology and the concept of ideology, I would like to start at another moment instead: the relationship of ideology and bourgeois culture [Bürgerlichkeit]. The theoretical motifs from the prehistory of the concept of ideology that I have reminded you of belong entirely to a world in which there was still no developed industrial society, and in which barely any doubt was stirred about whether the establishment of formal equality among citizens would also achieve freedom. Insofar as the question about the material life-processes of society had not yet arisen, all of the enlightenment doctrines addressing ideology had a certain priority: they believed that putting consciousness in order would be sufficient to put society in order. Yet this belief is not just bourgeois; it is the essence of ideology itself. As consciousness that is objectively necessary and at the same time false, as the conflation of the true and untrue, differing as much from the whole truth as from barefaced lies, ideology belongs not merely to modernity, but to the developed urban market economy. Because ideology is justification. It requires two things: firstly, the experience of an already problematic social situation, which therefore must be defended; and secondly, the idea of justice itself, which has equal exchange as its model, and without which such apologetic necessity would not endure. There really are no ideologies in situations ruled by bare, immediate relations of violence. Those thinkers of the restoration who poured praise on the relations of feudalism or absolutism are bourgeois; by their very form of discursive logic, that of argumentation, which itself contains an egalitarian, anti-hierarchical element, they undermine precisely what they glorify. A rational theory of the monarchical system¾something which ought to be founded on its own irrationality¾would sound like a lèse-majesté in any place where the monarchical principle still has substance; the foundation of positive power upon reason virtually does away with the principle of recognition of what exists. Accordingly, the critique of ideology is a confrontation of ideology with its own truth, and is only possible insofar as ideology contains a rational element upon which the criticism can set to work. This applies to ideas such as liberalism, individualism, and of the identity of the mind and reality. If, however, one wanted to criticize the so-called ideology of National Socialism, one would lapse into an impotent naïveté. Not only does the quality of Hitler and Rosenberg as authors scoff at every criticism; their lack of quality, the triumph over which counts only as the lowliest of pleasures, is a symptom of a state of affairs for which the concept of ideology as a necessary false consciousness simply no longer immediately applies.[12] Such a body of thought reflects no objective spirit. Rather, it is contrived manipulatively, as a mere means of domination; fundamentally no one expects that it will be believed or taken seriously, not even its authors. They refer to power with a wink: once you use your reason against it, you will see where you end up. In many cases, the absurdity of its theses is turned against people, so as to test out what they will go along with, so long as they hear the threat that lies behind the phrases, or otherwise accept the promise that they will receive some of the spoils. Where ideologies have been replaced by the diktats of the approved worldview, it is in fact the critique of ideology that has been replaced through the analysis of the cui bono. One may understand from this how little ideological critique has to do with the relativism with which it is so readily associated. Ideological critique is a determinate negation in the Hegelian sense: a confrontation of what is intellectual with its realization, and its presupposition is as much the differentiation of the true and the untrue within its own judgment as the claim to truth within what it criticizes. It is not the critique of ideology that is relativistic, but rather the absolutism of the totalitarian pummeling, the writs of Hitler, Mussolini, and Zhdanov, who do not call their enunciations ideology for nothing. The critique of totalitarian ideologies does not have to refute these, because they either raise absolutely no claim to autonomy or consistency, or they do so only in a completely shadowy way. On the contrary, totalitarian ideologues indicate far more that what should be analyzed is the dispositions of people upon whom they speculate, and what they strive to call up in people. That is a completely separate matter from the official declamations. Furthermore, the question remains that of why, and in what ways, modern society produces people who respond to such stimuli, indeed who require such stimuli, and whose spokesmen, to a large degree, are Führers and demagogues of all varieties. The development which leads to such transformations in ideologies themselves, and not just their content and structure, is necessary; the anthropological transformations for which the totalitarian ideologies are tailored are consequences of the structural transformations of society. It is only in this way that they are in some way substantial, and not in what they say. Today, ideology is the conscious and unconscious state of the masses as objective spirit, not the paltry products that emulate and undersell this situation in order to reproduce it. Ideology in the proper sense requires relations of power that are opaque, mediated, and to an extent milder. Today the use of such a term is wrong because society, wrongly scolded for its complexity, has in fact become too transparent for that.

Yet it is exactly this that is the last thing to be conceded. The less there is ideology, and the cruder its legacy, the more research into ideology promises to be able to measure the manifold of appearances at the expense of social theory. While in the Eastern Bloc the concept of ideology has been made into a torture instrument used against all insubordinate thoughts, and against those who dare to think them, in the West, with the softening up of the academic market, the concept of ideology has forfeited its critical content, and with that its relationship to truth. The first signs of this can already be found in Nietzsche, who meant something quite different, and who wanted to smash the pride that limited bourgeois reason takes in its own metaphysical dignity. Then, just as is found consistently today in positivist sociology, Max Weber contested the existence—or at least the cognizability—of any total structure of society and its relation to the mind. He demanded that one ought simply to pursue the interests of research into ideal types without prejudice, without the aid of any principle, and without consideration for what is primary and secondary. In doing so, he comes close to Pareto’s efforts. Max Weber restricted the concept of ideology to proving singular relations of dependence, thereby reducing it from a theory about the whole of society to a hypothesis about particular things we find before us, if not to a completely reduced “category of sociological understanding,” The same effect occurred when Pareto extended his famous doctrine of derivations so far that it no longer contained any specific differentiations. The social explanation of false consciousness becomes the sabotage of consciousness in general. For Max Weber, the concept of ideology is a prejudice that requires scrutiny; for Pareto everything intellectual is ideology. For both, the concept is neutralized. Pareto draws out the full consequences of sociological relativism. The intellectual world, insofar as it might be more than mechanistic natural science, renounces every truth-character; it dissolves into mere rationalizations of interests and the justifications given by every conceivable social group. An intellectual law of the jungle arises out of ideological critique: truth becomes a function of each enforceable power. Despite the appearance of radicalism, Pareto’s thought thus resembles the earlier doctrine of idols: he does not truly have a concept of history but instead only one of ideologies, in the form of “derivations” that are simply attributed to people. Although he emphatically raised the positivistic claim that he was conducting ideological research logico-experimentally, after the model of the natural science, and was faithful to the facts, and in this way was showing himself to be completely unchallenged by the epistemo-critical reflection of Max Weber, with whom he shared the pathos of value-freedom, he nonetheless used expressions like “tout le monde”or even “les hommes.” Pareto was blind to the fact that as social relations transform themselves, what he called human nature, and therefore also the actually driving motives, the residues, and their descendants, the derivations or ideology, are also affected. A characteristic passage from his General Treatise on Sociology reads:

Derivations, in a word, are things that everybody uses. […] hitherto, the social sciences have been theories made up of residues and derivations and furthermore holding in view the practical purpose of persuading people to act in this or that manner deemed beneficial to society. These present volumes aim instead at bringing the social sciences wholly within the logico-experimental field, quite apart from any purpose of immediate practical utility, and in the sole intent of discovering the uniformities that prevail among social phenomena […] But the person who aims at logico-experimental knowledge and nothing else must take the greatest pains not to fall into derivations. They are objects for his study, never tools of persuasion.[13]

By relating to humans-as-such instead of the concrete form of their socialization, Pareto falls back into the older, one might even say pre-sociological, standpoint of the doctrine of ideology: that is, a psychological one. There he remains with the partial knowledge that one must differentiate between “what a person says and thinks about himself, and what he really is and does,” without meeting the complementary requirement: “one would have to differentiate more still in historical struggles the slogans and fantasies of parties from their real organisms and their real interests, their conceptions of themselves from their reality.”[14] Ideological research is steered back, to a certain extent, into the private sphere. One might rightly note that Pareto’s concept of the derivation stands in close relation to the psychoanalytic concept of rationalization, as it was first introduced by Ernest Jones and was then accepted by Freud: “the human being has such a weakness for adding logical developments to nonlogical behaviours.”[15] The fundamental subjectivism in Pareto, which can be traced back to his subjective economics, addresses the untruth of ideologies improperly: not as social relations and objectively prescribed contexts of delusion, but instead as the ways that people give reasons for and justify their true motives after the fact. He does not inquire about that tangible element of truth in ideologies, which is comprehensible only in connection with objective relations and not with psychology: in their anthropological function ideologies simply exhaust themselves. The formulation that Hans Barth offers in Truth and Ideology applies: that for Pareto the intellectual world, insofar as it claims to be something other than the discovery of causal relations after the model of mechanics, possesses neither a lawfulness of its own, nor epistemic value. The scientistic presentation of the theory of ideology implies the resignation of science when confronted with its object. Because Pareto blinded himself to the reason that ideologies contain (counter to the Hegelian manner of conceiving of historical necessity), he gave up any rightful claim on reason in casting an overall judgement on ideologies. This doctrine of ideology is splendidly suitable, itself, as the ideology of a totalitarian power state [Machtstaat]. As it prematurely subsumes everything intellectual under the aims of propaganda and domination, it prepares a scientific clean conscience for cynicism. The relationship between Mussolini’s statements and Pareto’s tract is well known. Political late-liberalism, which with the concept of freedom of opinion possessed a certain affinity for relativism, insofar as everyone is allowed to think what he will, regardless of whether it is really true, because each will choose to think whatever is most favorable for his or her benefit or self-advantage—this liberalism was in no way immune to such perversions of the concept of ideology. This also confirms that the totalitarian domination of humanity was not perpetrated from the outside by a few desperados, that it does not appear as some traffic accident on the motorway of progress, but rather that the powers of destruction matured in the midst of culture.

By separating the doctrine of ideology from the philosophical theory of society, a type of pseudo-exactness is established, but the real epistemological power of the concept is sacrificed. This can be shown also to be the case where the concept was entirely absorbed into philosophy itself, such as by Max Scheler. In contrast to the formless levelling in Pareto’s doctrine of derivations, Scheler proposed a form of typology, if not an ontology, of ideologies. Today, not even thirty years later, his essay, which was once well-admired, sounds astoundingly naïve:

I offer the following as examples of such formal modes of thought determined by class:

2. Reflection upon becoming ↔ lower class; reflection upon being ↔ upper class.

4. Realism (world given predominantly as ‘resistance’) ↔ lower class; idealism (world predominantly a ‘realm of ideas’) ↔ upper class.

5. Materialism ↔ lower class; spiritualism ↔ upper class.

8. Optimistic view of the future and pessimistic retrospection ↔ lower class; pessimistic view of the future and optimistic retrospection (‘the good old days’) ↔ upper class.

9. Thinking that looks for contradictions, or ‘dialectical’ thinking ↔ lower class; thinking that seeks identity ↔ upper class.

These are subliminal forms of bias conditioned by class, in order to comprehend the world in primarily in one form or the other. They are not class prejudices, but more than prejudices: more precisely, they are formal laws for the development of prejudice, and thus as formal laws of predominant biases, in order to develop specific prejudices, have their roots only in the situation of class – completely separate from individuality. Were they to be completely understood, and grasped through their necessary emergence out of the class situation, they would immediately constitute a new lesson in the sociology of knowledge. I would like to designate this as a ‘sociological doctrine of idols’ of thought, views, and values, as an analogue to Bacon’s doctrine of idols.[16]

Despite Pareto being Scheler’s philosophical polar opposite, it is illuminating that this schema of upper class and lower class, which even in Scheler’s own view was all too coarse, shares with his thought the absence of historical consciousness, both in the concretion of the social structure and in how the development of ideology subtends this. The opposition between static-ontological and dynamic-nominalist thought is not only crude and undifferentiated, but false when compared to the structure of the development of ideology itself. What Scheler calls the ideology of the upper class, today broadly has an extremely nominalistic character. Existing relations are therefore defended by construing their critique as arbitrary conceptual constructions from above, or as “metaphysics.” Meanwhile research is supposed to take its orientation from unstructured data or “opaque facts.” Pareto himself offers an example of such an ultranominalistic apologia, and today’s preponderant social scientific positivism, which one can barely ascribe to the lower class of Scheler’s schema, demonstrates the same tendency. Conversely, the most important theories that Scheler would classify as ideologies of the lower class have stood in immediate opposition to nominalism. Their starting points are the objective total structure of society and an objective concept of a self-unfolding truth with a Hegelian provenance. Scheler’s phenomenological procedure, as a philosophy that measures itself against purportedly demonstrable entities, and does so passively, while renouncing construction, still also falls into a positivism of a second order in his late phase¾into a spiritual positivism as it were. But wherever the object is not constructed by the concept, the object itself escapes the concept.

In Scheler and Mannheim the theory of ideology is made into the academic branch of “the sociology of knowledge.” The name is significant enough: all consciousness, and not just the false but also the true, even knowledge, will be governed by the proof of its being socially conditioned. Mannheim prided himself on the introduction of a “total concept of ideology.” In his magnum opus Ideology and Utopia, it is described in this way:

With the emergence of the general formulation of the total conception of ideology, the simple theory of ideology develops into the sociology of knowledge. […] It is clear, then, that in this connection the conception of ideology takes on a new meaning. Out of this meaning two alternative approaches to ideological investigation arise. The first is to confine oneself to showing everywhere the interrelationships between the intellectual point of view held and the social position occupied. […] The second possible approach is nevertheless to combine such a non-evaluative analysis with a definite epistemology. There are two separate and distinct solutions to the problem of what constitutes reliable knowledge—the one solution may be termed relationism, and the other relativism.[17]

It seems difficult to seriously differentiate the two possibilities that Mannheim foresaw for the uses of the total concept of ideology. The second—that of an epistemological relativism, or with the nobler word, relationism, does not form any real opposition to the first, to which Mannheim contrasts it—that of the value-neutral study of the relations of the “situation of being and vision,” and therefore also of base and superstructure. Rather, this epistemological relativism attempts in all cases to shield the procedures of a positivistic sociology of knowledge through methodological reasoning. Mannheim was comfortable that the concept of ideology would only be justified in describing false consciousness, but such a conception is no longer capable of describing content, so he postulated the notion only formally, as an allegedly epistemological possibility. Here, ideology’s general worldview takes the place of determinate negation, and then, following the example of Max Weber’s sociology of religion, the particulars empirically demonstrate relationships between society and the intellect. The doctrine of ideology breaks in two: on the one hand, the highest abstractions of a total project that evades concise articulation; on the other, monographic studies. The dialectical problem of ideology is lost in the vacuum between these two: that there certainly is false consciousness, but it is not only false. The veil that necessarily falls between society and its insight into its own essence simultaneously expresses this essence by virtue of such necessity. Real ideologies become untrue only in relation to existing reality. Ideas can be true “in themselves,” as are freedom, humanity, and justice, but as ideologies they behave as if they were already realized.[18] The labelling of such ideas as ideologies, which is permitted by the total concept of ideology, in many ways testifies less to the irreconcilable opposition to false consciousness, and more to the rage against that, which were it to exist, even if only as powerless intellectual reflection, could point to the possibility of something better. Someone once rightfully said that in many cases those who disdain those same ideological concepts are not thinking so much of the misused concepts as what they stand for.

In closing, instead of entering into theoretical debates about how the concept of ideology could be formulated today, I would like to initiate a discussion with the aim of giving you some indications of the concrete contemporary form of ideology. Indeed, the theoretical construction of ideology depends both on what is actually efficacious as ideology, and, conversely, on the presupposition of the definition and penetration of ideology by theory. Let me first appeal to an experience—one that none of us can avoid: that something decisive has changed in the specific gravity of the mind. If, for a moment, I might recall that art is the most faithful historical seismograph, it seems to me that without a doubt there is a weakening, which places contemporary art in the most extreme contrast to the heroic era of modernism around 1910. Whoever thinks socially cannot be content to ascribe this weakening, from which other intellectual realms such as philosophy are hardly spared, to the so-called decline of creative powers, or to evil, technical civilization itself. In thinking socially, one would instead find traces of some kind of tectonic shift. Countering the catastrophic processes in the deep structures of society, the intellect has assumed for itself the form of something ephemeral, thin, impotent. In light of contemporary reality, it can barely make the unbroken claim to seriousness in the way that nineteenth century believers in culture naturally did. The tectonic shift—literally between the strata of the superstructure and the base—extends to the most subtle of immanent problems of consciousness, and of the shaping of the intellect. It is not that these powers are missing, but rather that they are crippled. Any intellect that does not reflect on this, and which goes on as though nothing had happened, seems to be condemned in advance to helpless vanity. If the theory of ideology has always reminded the intellect of its frailty, today its self-consciousness would also have to face this aspect; one could almost say today that consciousness, which Hegel essentially already defined as the moment of negativity, can survive only so long as it incorporates the critique of ideology into itself. One can only sensibly speak about ideology as though it were an autonomous, substantial, intellectual entity which has emerged out of the social process and makes its own claims. Its untruth is always the price of this detachment, of the disavowal of the social basis. But its moment of truth clings to such autonomy, to a consciousness that is more than the mere reproduction of what exists, and it therefore strives to penetrate what exists. Today, the signature of ideology is more the absence of this autonomy than the deception of its claim. With the crisis of bourgeois society, the traditional concept of ideology seems to have lost its object. The intellect splits apart into a truth which is esoteric, critical, in that it externalizes itself from semblances, and is alienated from the immediate social context; and the planned administration of that which was once ideology. If one were to define the legacy of ideology as the totality of all intellectual products, which today occupy the consciousness of people to a great extent, then one may understand by this less an autonomous mind deceived about its real social implications, than a totality of what is manufactured in order to capture the masses as consumers and, if possible, to model and fixate their state of consciousness. Today’s socially conditioned false consciousness is also no longer an objective spirit, in the sense that it in no way crystallizes blindly and anonymously out of social processes, but instead is scientifically tailored to fit society. This is the case for all products of the culture industry: films, magazines, illustrated papers, radio, bestseller literature of the most various types, of which the novel-biographies play their particular role, and now, in America above all else, the television. It goes without saying that the elements of these are not new, and are petrified into a very uniform ideology, in contrast to the breadth of techniques used for its dissemination. They draw on the traditional distinction, already indicated in antiquity, between the higher and lower spheres of culture, in which the lower is rationalized and is integrated into the derelict residues of the higher spirit. Historically, the schemata of the contemporary culture industry can be traced back, in particular, to the early times of English vulgar literature, around 1700. This literature already uses most of the stereotypes that today grin at us from the silver screen or the television. Social reflection on qualitatively new phenomena ought not to be duped by taking note of these venerably old constituent parts, and consequent arguments based on their age about the fulfilment of primal needs. This is because this ideology does not depend on these constituent parts, nor does it depend on the fact that the primitive movements have remained the same in mass culture as they had been throughout the epochs of an immature humanity. Rather, they depend on the fact that today everything is absorbed into a regime, and that the whole is made into a closed system. Escape is barely tolerated anymore. People are encircled on all sides, and regressive tendencies, which are otherwise released by the increasing social pressure, are promoted through the achievements of a perverted social psychology, or as it was once aptly named, inverted psychoanalysis.[19] Sociology has seized this sphere under the title of “communications research,” the study of the mass media, and in this way has laid a special emphasis on the reactions of consumers and the structure of the interplay between them and the producers. This is not to deny that such undertakings, which rarely disavow their origins in market research, have a certain cognitive value. But to me it is more important to consider the so-called mass media in terms of ideology critique than to content oneself in addressing their mere existence. Such tacit acceptance through descriptive analysis itself constitutes an element of ideology.

In the face of the indescribable power that the media wield over humanity today—which, incidentally, in a broad sense also includes sport, since it was long ago transformed into ideology—determining their concrete ideological content is immediately urgent. This aims towards the synthetic identification of the masses with norms and relations, be they anonymous and standing behind the culture industry, or be they conscious and propagated by it. Censorship is used against all who dissent; conformism is drilled into even the most subtle of emotional reactions. In this way the culture industry is able to play the role of objective spirit to the extent that it is able to draw on anthropological tendencies awake in those consumers whom it supplies. It seizes these tendencies, strengthening and confirming them, while all that is insubordinate is left behind or expressly thrown out. The rigidity of thought, which lacks all experience, that prevails in mass society is hardened further by this ideology where possible, while, at the same time, in an exaggerated pseudo-realism, it delivers an exact likeness of empirical reality in every external respect. In this way it prevents us from seeing through what it offers as something already preformed, as though subject to social control. The more alienated people are from fabricated cultural goods, the more they are persuaded that they are dealing with themselves and their own world. What one sees on the televisions seems all too comfortable. Meanwhile, though, the contraband of slogans, such as that foreigners are all guilty, or that career success is the highest thing in life, are smuggled in as though they were forever given. If one were to condense what the ideology of mass culture comes down to into a single sentence, one would have to represent it with the parodic statement: “become what you are”—as the superelevated justification and duplication of a state of affairs that exists anyway, implicating all transcendence and all criticism. In that the socially effective intellect limits itself to once again placing before people’s eyes only what already determines their existence, while at the same time proclaiming this existence as its own norm, it fixates people through their faithless faith in pure existence.

Nothing remains of ideology other than the acceptance of the status quo itself, as a model of conduct that acquiesces before the supreme power of conditions. It is hardly an accident that the most effective metaphysics today is attached to the word “Existence,” as though the doubling of mere being through the highest of abstract determinations that are drawn from it is coterminous with its meaning. This largely corresponds to the situation in people’s heads. They no longer tolerate as an idea—as they might still tolerate the idea of the bourgeois system of nation-states—the absurd situation in which, in the light of the open possibility of happiness, every day they are threatened with an avoidable catastrophe. Yet they settle for the given in the name of realism. In advance, individuals experience themselves as though they were chess figures, and calm themselves in doing so. But beyond that, ideology amounts to little more than that things just are how they are, and its own untruth has been reduced to the tenuous axiom: it could not be any other way than it is. While the people bow down to this untruth, they secretly see right through it at the same time. The glorification of power and the irresistibility of mere existence are at the same time the very condition for its disenchantment. Ideology is no longer a veil, but now only the threatening countenance of the world. Not only by virtue of its interweaving with propaganda, but by its own form, it devolves into terror. But because ideology and reality converge to such an extent—because reality becomes an ideology of itself in the absence of any other convincing ideology—it would require only a small effort of the mind to throw off the semblance that is at once both omnipotent and futile.

1954.

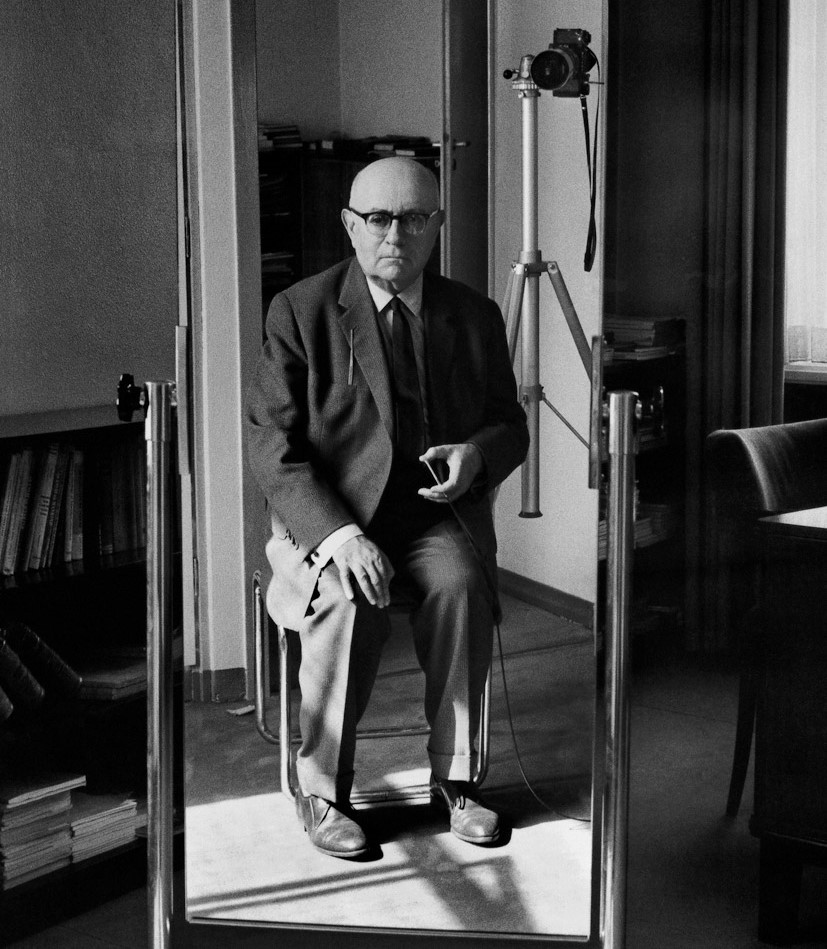

This contribution belongs to the context of continued collaborative work with Max Horkheimer. The author sincerely thanks Messrs Heinz Maus and Hermann Schweppenhäuser for their assistance.

- [1] E. Spranger, ‘Wesen und Wert politischer Ideologien’ [‘Essence and Value of Political Ideologies’], in: Vierteljahreshefte für Zeitgeschichte [Contemporary History Quarterly], 2 (1954), S. 118 ff.

- [2] [Adorno is referring here to Martin Heidegger. In The Fundamental Concepts of Metaphysics: World, Finitude, Solitude, he wrote,‘Yet this transformation of seeing and questioning is misunderstood when it is taken as a change of standpoint or as a shift in the sociological conditions of science. It is true that this is the sort of thing which mainly or exclusively interests many people in science today—its psychologically and sociologically conditioned character—but this is just a facade. Sociology of this kind relates to real science and its philosophical comprehension in same the way in which one who clambers up a façade [Fassadenkletterer] relates to the architect or, to take a less elevated example, to a conscientious craftsman.” trans. William McNeill and Nicholas Walker, (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1995), p.261; Martin Heidegger, Gesamtausgabe 29/30, Grundbegriffe der Metaphysik: Welt – Endlichkeit – Einsamkeit, ed. Friedrich-Wilhelm von Hermann, (Frankfurt am Main: Vittorio Klostermann, 1983), p. 379. Adorno first addressed this figure in his inaugural lecture in 1931, ‘The Actuality of Philosophy’, trans. Benjamin Snow (pseud. Susan Buck-Morss) in Telos, No. 31, 1978, p. 130; Gesammelte Schriften, ed. Rolf Tiedemann, Vol. 1, p. 340. The figure would be addressed again in terms similar to those found here in Adorno’s later lectures, such as Philosophy and Sociology (1960), ed. Dirk Braunstein, trans. Nicholas Walker, (Cambridge: Polity, 2022), 6.—Translator’s notes in brackets here and below.]

- [3] Francis Bacon, The New Organon, eds. Lisa Jardine and Michael Silverthorne, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), p. 42. Compare with Hans Barth, Truth and Ideology,trans. Frederick Lilge, (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1976), p. 19; Wahrheit und Ideologie, Zürich 1945, p. 48; The author is indebted to Hans Barth’s work for providing many pieces of evidence about the development of the concept of ideology.

- [4] Theodor Geiger, ‘Kritische Bemerkungen zum Begriffe der Ideologie’ [‘Critical Remarks on the Concept of Ideology’] inGegenwartsprobleme der Soziologie [Contemporary Problems of Sociology], Potsdam, 1949, p. 144

- [5] Claude Adrien Helvétius, De l’Esprit [On Spirit], cited in Hans Barth, Ideology and Truth, p. 35; Ideologie und Wahrheit, (Zürich: Manesse Verlag, 1945), p. 65.

- [6] Claude Adrien Helvétius, De l’Homme, [On Humans], cited in Hans Barth, Ideology and Truth, p. 35; Ideologie und Wahrheit, p. 66.

- [7] [Adorno is mocking Wittgenstein’s Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, which famously opens with the statement “The world if everything that is that case.” Adorno considered this type of positivism to fail because reason itself becomes insuperably enmeshed in the givenness of an irrational world,]

- [8] Paul-Henri Thiry d’Holbach, Système de la Nature, [The System of Nature], cited in Hans Barth, Ideologie und Wahrheit, p. 69; [This passage does not appear in the English translation of Barth’s book; the English translation is also an abridgment, see the translator’s note, p. xvii.]

- [9] Claude Adrien Helvétius, De l’Esprit [On Spirit], cited in Hans Barth, Ideology and Truth, p. 35; Ideologie und Wahrheit, p. 62.

- [10] Moniteur universel, Paris, Dec. 21, 1812, p.2, cited in Vilfredo Pareto, The Mind and Society: A Treatise on General Sociology, trans. Andrew Bongiorno and Arthur Livingston, (New York: Dover, 1935), Vol. 2, pp. 1244-1245.

- [11] [Adorno is here referring to role of ideology within the dogma of Stalinist dialectical materialism.]

- [12] [Although Adorno does not go into any detail here, the definition of ideology as “socially necessary illusion” would become important in his later work, especially Negative Dialectics, p.197. The definition likely arises from Lukács’s discussion of necessary illusion in History and Class Consciousness, 92.]

- [13] Vilfredo Pareto, The Mind and Society: A Treatise on General Sociology, trans. Andrew Bongiorno and Arthur Livingston, (New York: Dover, 1935), Vol. 2, pp. 890-891.

- [14] [Although not attributed in Adorno’s original text, these two quotations are taken from Chapter 3 of Karl Marx’s The 18th Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte.]

- [15] Pareto, The Mind and Society, Vol. 2, p.104. [In the previous clause Adorno is referring to Ernest Jones’s essay ‘Rationalization in Every-Day Life’, The Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 1908, Vol. 3/3, pp. 161-169.]

- [16] Max Scheler, Problems of the Sociology of Knowledge, trans. Manfred S. Frings, (London: Routledge and Kegan, 1980), pp. 169-170; Die Wissensformen und die Gesellschaft, (Leipzig: Der Neue Geist Verlag, 1926), p. 204.

- [17] Karl Mannheim, Ideology and Utopia, trans. Louis Wirth and Edward A. Shils, (London: Routledge and Kegan, 1936), pp. 69-70; Ideologie und Utopie, 3rd Edition, (Frankfurt: Schulte-Bulmke, 1952), p. 70.

- [18] [This argument that the objective form of ideas is more than a mere expression of interest is borrowed from Hans Barth’s book without credit. Barth uses this argument to attack Marx’s theory of ideology, pp. 104-105, and reiterates the centrality of this argument in the book’s conclusion, pp. 193-194.]

- [19] [This phrase was coined by Leo Löwenthal and would later be adopted by Adorno.]