First of all, it must be admitted… (1968)

Translator’s note: This text was produced in connection with a display of Buraglio’s 1968 work Mondrian camouflé (Camouflaged Mondrian). Although never formally a member of Supports/Surfaces, Buraglio was close to the group. Published as “Préalablement, il faut admettre…” in: Buraglio, Écrits entre 1962 et 2007 (Paris: Beaux-arts de Paris, 2007), 34-39.

First of all… it must be admitted that there can be no question but of painting and of nothing less than painting. This contradiction and this excess are necessary for the manifestation of a certain subversion. This subversion must first be exercised with regard to painting itself—painting is built on its own ruins—and finally against society. Here and now.

The dominant class controls all means of cultural dissemination, of cultural penetration: it is within these that subversion may cut its furrows, or break out in spots.

The function of painting that aims to be subversive is to seek out—in artistic, intellectual, and commercial circles, galleries, salons, biennials, journals—whatever it can undermine from within.

But not in just any old way.

The goal is not to make a thing or things; the goal is the truth of what you make.

Result and process confounded, the plastic effect happily forgetting itself (an effect that may moreover be the consequence of all the usual stylistics and techniques)—it’s the painter’s conduct that should be of interest.

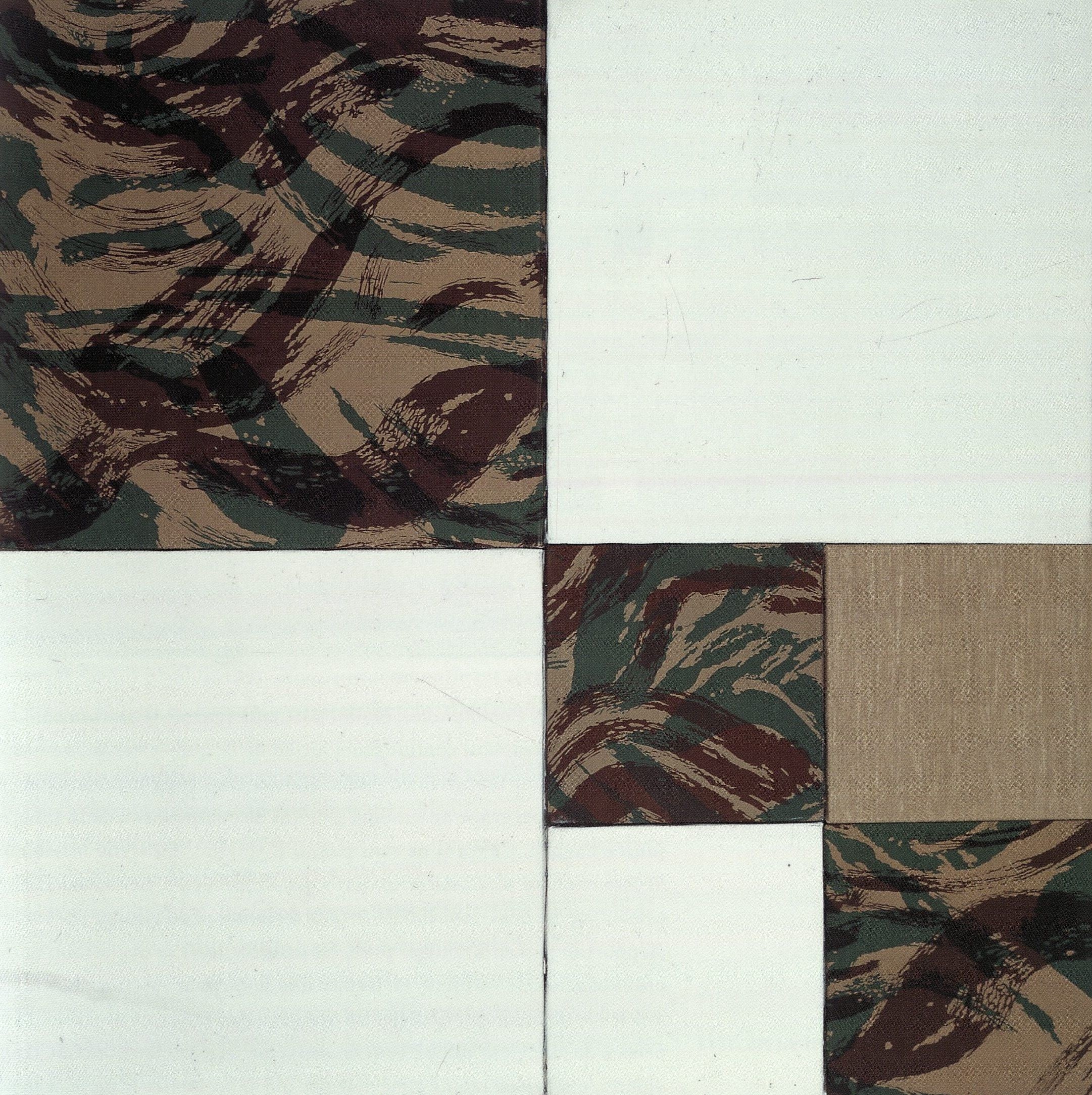

It’s necessary to read this subversion literally as what it shows itself to be; these camouflaged surfaces and these white surfaces (vinyl paint). It has to be accepted on its own terms without recourse to extrapictorial mediations.

To conceive the practice of painting as the field in which is manifested, exhibited, our non-freedom. Indeed, it is against the anonymous and confining ground of painting that the painter, in the least spontaneous way, develops his discourse. Consciously critical.

Work that limits itself to being only an interval, a permanent reference to the paintings that underlie it; to the painters who, since Cézanne, have interrogated the language of painting; who exhaust it.

It is necessary to admit this painting as indication.

Mute discourse, and yet indicative.

Its efficacity (but don’t overestimate it—because this is a matter of art, of painting) is proportionate to its apparent indifference to History.

(Apparent “bracketing of the world”).

This painting has developed the characteristic common to the art of exploiting classes in decline: the contradiction between political content / artistic form.

It camouflages itself behind its artistic form: exasperated abstract formalism. In order to reach the goal already announced: to work on painting from within. To be inside (within bourgeois culture)—and, dialectically, to escape from it. Once this goal has been indicated, it is necessary to explain how to go about the work, the methods employed, the tools used.

To clarify the constraints, the demands, that this practice imposes. These are neither of an aesthetic nor an ethical order. They can be explained as follows… Let us summarize: to effect a certain cultural subversion, it is necessary that a certain painting be fabricated. The realization depends on whether certain conditions are satisfied.

The production of these surfaces is critique in action. Painting puts its object to the test, by putting itself to the test of its object. Critique and self-critique.

These surfaces, like real and material critique, precede this text. However, this text accelerates the process.

Painting foreign to all representation, to all spectacle (Lyrical Abstraction is spectacle). These camouflaged and white surfaces present themselves. Nothing is represented on these surfaces. They act and do not react.

The absence of all representation is implicit in the painter’s project. This is not an end in itself. Painting of presentation is not opposed to representational painting, but differs from it.

To present means to render present. What is said is not separated from the singular moment in which it is said. The painter’s action is contemporaneous with what is presented (it applies to this exact concomitance). The viewer’s perceptual experience coincides with the evidence of making.

The viewer witnesses the event of the picture. The surfaces, their painter, and the viewer are all present at the same scene. What is shown has not been constituted through the advent of a spectacle of forms, whether figurative or otherwise: to look is to witness its perpetual event. This making-present must serve to protect the discourse that these surfaces materialize. Indeed, the truth of the painter’s work is threatened with obliteration by the merchandise with which it is confused. The practice of such a painting is the site and moment of the following contradiction: this practice is the event, and therefore History; History, in fact, through the transformation of the chosen support; in experimental space (see above). Presentation posits its space. Perceptible space is that which is contained within the limits of the painting’s frame. As soon as this space is no longer figurative but literal, no longer diffuse or mobile, as soon as it no longer measures a fictional space, but rather presents its own measurement: it identifies itself with the four sides of the frame, by simultaneously doubling it and at the same time affirming its difference from the frame (the wooden stretcher that grips it tightly).

An event, insofar as this space (this superficies) both remains a surface and becomes a screen. Now, the viewer who is isolated from the memory of things in his extreme dependence on vision will not be distracted. Vision of a manifest illegibility; left anonymous.

I do mean (manifest) illegibility, illegibility legible as such.

These surfaces do not communicate.

This union is the seizure; immediate and global seizure of those superficies (202 x 180 cm) that both remain surfaces and become screens. Against which the viewer stumbles. But the viewer is not left before an abstract picture, that is to say as if plunged into the bottom of a cup of Turkish coffee, or left to suffer, or to wander. The picture must establish an active relation with the viewer.

It is a fact that these combined surfaces (camouflage and white paint) say nothing to those who look at them. It is a fact that the painter says nothing, except in saying it, repeating it—which is not silence, which is not abstention—on the contrary; at this point at which critics, commentators, and the public are led more and more to speak up; and in a useful way: by raising questions based on the discourse that these surfaces materialize, questions that pass far beyond this discourse. Hence this is not a neutral silence; it would be a misunderstanding to think so. These surfaces want to say nothing; they are situated beyond meaning. They have no preexisting meaning. What they enunciate refers only to themselves. They depend on no meaning.

The correct reception of the discourse depends on the fact that not only do these surfaces represent nothing, express nothing, they also demonstrate nothing, they propose precisely nothing.

To signify, for such a painting, would be the obliteration of its signification.

To be silent—To be silent: in order to cause speech.

These surfaces that say nothing, that have no meaning. What do they make us see, perceive, sense?

A material presence that manifests an absence, rendered without symbolism, by the mere presence of these surfaces.

The absence of all representation, demonstration, etc., conjoined to that of the painter, of the operator, constitutes a situation of silence inherent to the product. As soon as it is produced: vector of silence.

Absence of the operator from the conceptual point of view. The product is detached from the ideas and the opinions of its producer; distinct.

In place of the relation of the artist to his work, such a practice substitutes the product and its painter, who is secondary in relation to what he has produced.

From the technical point of view… he effaces himself in the course of his operations… restrained sensibility, minimal, mechanized interventions, an economy of means.

Mechanization contributes, as a practice, to the subversion of idealist notions of the creator, of natural gifts, of the individual oeuvre.

The painter not only ceases to be privileged, but also renounces the imposition of his individual vision on the world. It is not only that he does not speak of himself, but that he says nothing at all, all while saying this, while repeating it. This is not—it must be repeated: silence, abstention. The silence of these surfaces is not neutral.

These surfaces make reference: their economy refers to pictures, to series of pictures (to painters) that systematize a certain development of modern painting.

This painting reproduces that development; in the experience of these limits. These limits were first indicated, in principle as well as chronologically, by Cézanne, then by Analytic Cubism, and were finally attained in both theory and practice by Mondrian and Pollock and by painters such as Parmentier, Buren.

This referential field…

In the series of canvases that each of these artists painted, each during a specific historical period, we can decipher the following problematic: the relation form/ground, otherwise known as the relation of the support (of the canvas) to what is painted atop it.

The abovementioned painters are the milestones of a history within History—that of painting taken as its own subject. The trait common to all these painters is their attempt, on the one hand, not to represent, not to symbolize, not to express; on the other hand, their attempt to carry out, with the means available at the time, the process of the production of representation.

…Progressive destruction of representation (flattening of the figure, etc.). Putting into question representation as a vehicle of exchange.

On our non-freedom, again

Submission to this anonymous and constrictive reality, submission to this ground of painting to which the painter is deliberately tied, makes it impossible to paint as one wishes at the very moment in which it has been proclaimed that painting is finally free.

How can one pretend to be free in a society that is not?

Bourgeois society encourages and valorizes novelty.

Artists thus have the task of producing the new. Why?

Because novelty does not put anything in question.

The persistence of values is not at all threatened by a change of forms. Taken as an end in itself, research and production only serve to better lend to art the mask of universality.

Bourgeois society claims that the artist is free, has won his freedom. Bourgeois society censors artists precisely through creative freedom. They are not actually able to conceptualize their relation to society, their state of extreme ideological and economic dependence. The practice of painting understood as its own subject is the field in which the operator of these surfaces acts and consumes (has already consumed) the resources available to him.

He is well and truly blocked.

He must repeat, paraphrase, cite, as did Mondrian, as did Lyrical Abstraction. It is a matter of showing that such painting, taken to its limits, runs up against the wall that it has itself erected. It is time to stop.

In conclusion—some remarks on the reading of Althusser.

We know that the break does not come out of thin air, that we need words to break with words, ideas to break with ideas. We know that is often old words that are charged with rupturing protocol, even as the search for new ones goes on. The same is true for the practice of painting, if one is determined to engage in a process of deep rather than superficial rupture.

We know that ideological consciousness does not in itself contain anything that escapes from its internal dialectic, does not permit an exit into reality by virtue of its own contradictions—furthermore, alongside this practice that exerts only a slow and very limited effect, it is quite possible to carry on work that is immediately useful, that coincides perfectly with designated propaganda objects.

Example: the Red Room for Vietnam (25 pictures, each 2 x 2 meters) in the service of the Vietnamese people.[1]

The insertion into studios of posters such as those of the Atelier Populaire des Beaux-Arts de Paris, in the service of the strike movement of May ’68.

- [1] Translator’s note: The reference is to an exhibition organized by the French artists’ association Jeune Peinture, originally planned for the spring of 1968 but postponed to January 1969 on account of the May uprising. Buraglio submitted a figurative painting of Nguyễn Hữu Thọ, a leader of the Việt Cộng. This picture is unique in the artist’s work of the period, which was otherwise strictly abstract.