Form and the Postwar Neo-Avant-Garde: Allan Kaprow’s Critical Writing

Allan Kaprow’s early critical writing on his art and that of his contemporaries deserves close attention, not just for what it reveals about his practice as a pioneering figure of the postwar so-called neo-avantgarde, but also for broader insights it offers into major shifts in ways of thinking about modern art taking place in New York at the time.[1] It combines an ostensibly casual everyday rhetoric with undeniable analytic astuteness and critical insight. This critical writing has considerable claim to an afterlife in its own right alongside his art world reputation as the supposed inventor of the happening. It consists of essays and articles published in widely-circulated art journals such at Art News over the period from the late 1950s to the late 1960s, as well as a longer theoretical and critical statement accompanying his book Assemblage, Environments and Happenings, published in 1966.[2] The moment was a crucial one in the American art world. It came in the immediate wake of Abstract Expressionism establishing itself as the latest phase of a history of ongoing radical modernist or avant-garde innovation. The younger generation of radically experimental artists who were beginning to make their mark at this moment, however, categorically rejected, in theory at least, the high modernist formalism associated with this recent reconfiguring of modern abstract painting. Commonly designated as neo-avant-garde,[3] they experimented with a variety of alternative practices, amongst which happenings of the kind championed by Kaprow were for a moment a particularly important instance. A central argument of this article is that these initiatives were not categorically anti-form, even as they were reacting against the formalist orthodoxies associated with high modernism. While anticipating subsequent “postmodernist” or “poststructuralist” tendencies, they remained more invested, ethically and aesthetically, in the rigors of a broadly modern preoccupation with issues of artistic form.

Two key issues are brought into sharp relief by Kaprow’s contributions to theoretical and critical debate around the artistic formation and ethical and political imperatives shaping postwar developments in a self-consciously modern art, variously designated as modernist or avant-garde.[4] The first part of the article examines the attentiveness to issues of artistic form that emerges in the course of Kaprow’s attempts to formulate a conception of a non-art that dispensed with the limits imposed by the artificial formalism of orthodox high modernism, and come closer to the “real” rhythms and patternings of everyday life. What persists is a distinctively modern, even modernist, commitment to the significance of form,[5] manifesting itself in the first instance in Kaprow’s finely-wrought analysis of the formal complexities of works of painterly abstraction he particularly admired, but whose structural underpinnings he felt he had to abandon in further efforts at radical artistic experimentation. The second part examines the broader imperatives Kaprow saw as driving avant-garde or experimental practice, and shows how shifts taking place in his thinking expose key aspects of larger, longer-term changes taking place in the political imperatives of a radical modern or avant-garde practice. Such shifts eventually led to the demise, loosely associated with postmodernism, of the whole idea of an artistic avant-garde whose formal radicalism would offer a challenge, more or less overtly political, to modern society’s hegemonic norms. The analysis is filled out by comparing the trajectory of Kaprow’s thinking in this respect with that of the Marxist-inclined art historian and critic Meyer Schapiro. A figure from an earlier generation, formed in the interwar period, who subsequently had a considerable impact on the American art world of the 1940 and 1950s, and under whom Kaprow briefly studied, he played a significant role in shaping Kaprow’s thinking about art. He also, like Kaprow, was alert, if in a very different way, to the ideological ramifications of the changing nature of artistic experimentation that they both witnessed and, to a greater degree in Kaprow’s case, participated in. Considering the affinities and differences between the two makes for an illuminating perspective on larger currents of thought that played a key role in the postwar American art scene.

Form

Kaprow’s critical writing on art takes two forms. On the one hand there are his close formal and structural analyses of abstract modern artworks he particularly admired, as well as his astute anatomizing of experimental tendencies in recent art. On the other are his accounts of the guiding principles of his happenings and their larger raison-d’être. At times, the latter blur into the former as they extend beyond apologias for happenings to become reflections on the larger condition of contemporary art.[6] Kaprow became best known for promoting the idea of a non-art that sought to realize itself outside the framing and structuring of a conventionally recognizable art practice. At the same time, he remained seriously preoccupied by issues of artistic form, to the extent of producing some of the finest critical writing of the period on the complex formal logic at work in recent abstract painting. This concern with formal issues never entirely disappears. In fact, his invocations of the anti-aesthetic and the non-artistic were designed in part to give the logic and necessity of form a more compelling grounding than dominant understandings centered exclusively on art allowed. Kaprow is an interesting case in point because he put such pressure on this apparent paradox, thereby throwing into question standard assumptions about the abandonment of form as a defining issue of the post-Abstract Expressionist neo-avant-garde.

Kaprow’s most fully-elaborated analysis of artistic form comes in an essay titled Impurity published in Art News in 1963.[7] In it he developed a suggestive comparison between the apparent chaos and impurity of Pollock’s freely gestural painting, on the one hand, and the finely-tuned, rigorously geometrical purism of Mondrian’s abstraction or the minimalist purism of Barnett Newman’s color-field painting, on the other. He began with a disquisition on the larger significance of art-world ideas of purity and impurity. These terms, he argued, form an interdependent polarity—impurity is unthinkable without purity—and much more is at stake in the choice the artist makes between them than matters of an exclusively artistic nature. They have gained their purchase as ways of understanding the nature and structure of reality, of defining the goals of human and natural activity and of explaining “the world’s events as an ethical passage from one condition to the other.”[8] Purity brings to mind the valuing of the rational and non-empirical, and also moral qualities such as refinement and spirituality, as well as metaphysical conceptions—the essential, true and absolute. Impurity on the other hand defines itself as the negation or sullying of purity. It is a “second-hand state, a mongrel at best physically; therefore tainted morally; metaphysically impossible by definition.” Such a state lies at the basis of ideas of the romantic, and at times, when “romantic thoughts prevail, impurity is scrawled over the earth as a truth of nature more honest than any classical artifice.”[9]

The extended analysis he offers of carefully selected individual artworks performs a virtuoso reversal between these polarities. In his close reading of works by Pollock, Mondrian and Barnett Newman,[10] he shows how what initially comes across as classical order and poise can be seen to disintegrate and give way to impurity and unboundedness, while alternatively, what at first appears redolent of chaos and disorder can momentarily stabilize in a precarious moment of “pure harmony.”[11] The point of departure for his painstaking anatomizing of Piet Mondrian’s Composition 2, 1922[12] is clearly indebted to Meyer Schapiro, under whose supervision he had written an MA dissertation on the artist. Schapiro did not envisage a stable sense of Platonic order emerging from Mondrian’s ostensibly highly-regulated arrangement of pared-down abstract lines and geometrical fields of color in the painting. What the artist achieved, in his view, was a dynamic as distinct from a static equilibrium. On careful examination the fixed order that the work might at first seem to represent gave way to something more asymmetric, freely engaged, and open.[13]

Kaprow had in mind a more radical and intensely charged transition from the initial semblance of classical fixity than did Schapiro. As a result of the “prolonged and unblinking gaze,” Mondrian’s radical abstraction demands if it is to be seen and felt properly,” he explained, an initial semblance of classical stability and containment dissolves into “a myriad of changing substances and positions… We become another unfixed point in immeasurable space, one more reciprocating rhythm in a charged void. We are no longer rooted in time or in any space. Still as long as we remain conscious of our task to account for every phenomenon in the work… we are yet in this world.”[14] A succession of dialectical reversals unfold. “The data of vision cumulatively annihilate themselves, but it takes our eyes to accomplish this, and we become increasingly sensible of their role in bringing about this exaltation,” thereby “precipitating a crisis of consciousness and identity.”[15] In this way, Mondrian brings us to “the brink and the abyss on the other side of which is purity,”the purity he was constantly struggling to achieve through an art necessarily grounded in matter and sensation.[16] Kaprow concluded with a compelling evocation of the expansive and intensely charged vision which Mondrian sought to realize through his painstaking formal procedures. His ceaseless artistic effort, he explained, is “essentially a purgatorial exercise of the loftiest kind, qualified and given meaning by the imperfection of the world he lived in and hoped to improve by his difficult example… That he was part of this world […] is implicit and makes his works poignant”—this “is their romanticism and impurity.”[17]

Kaprow’s analysis of Pollock’s expansive monochrome canvas Composition 32, 1950[18] takes off from the immediately felt, pervasive and engulfing sense of romantic impurity. He then goes on to detail how the intensely chaotic initial appearance of scattered paint work eventually yields to a radically different apprehension of the work. On closer examination, an awareness emerges of the “natural rhythm” of a repeated gesturing creating trails and blobs of paint on the canvas. This permitted Pollock the “liberty of alternately enflaming and drenching the entire canvas by only varying it slightly”—so that after a certain time “the conflagration suddenly freezes over, and motion stops.”[19] Momentarily a harmony takes over as the image created “reverts to its enigmatic space on the wall, and acquires a cool almost fragile independence,” though this doesn’t stabilize matters: the “impulse to movement returns; the vertiginous ride always starts again.”[20]

Kaprow is not just making the point that any significant abstract art, in his view, is activated by an unstable compound of purity and impurity. He is also claiming that entire worldviews are caught up in this compound. Like a number of his near-contemporaries who are seen as pioneers of an anti-formalistic turn—Eva Hesse might come to mind here—he had a keen awareness of the huge ambitions that energized a practice based on a systematically pursued, radical unstructuring and restructuring of artistic form. But he took the view that this visionary dimension of early modernist and recent abstraction could not now be repeated or reactivated. A truly compelling art, one that carried something of the same ethical charge, had to break out of the framing that determined both the possibilities and limits of these latest experiments in radical abstraction. It would also need to locate itself outside confines of the formal analytic tradition that still set the terms for his compelling critical evaluations of works of high abstract art.[21]

In his view, such a new departure was not to be realized by taking an ideological stand against form as such. In 1968, he published an article in Artforum criticizing Morris’s notion of anti-form: anti-form, in Morris’s case, standing for various new kinds of open processoriented work deploying unformed or largely unformed materials.[22] Morris represented his new, freely-arrayed felt pieces and their departure from the residual modernist formalism of his earlier, rigorously geometric Minimalist work as exemplifying this new anti-form ethos.[23] Kaprow responded, first by showing how even a recent, particularly casual-looking, but also dense hanging felt piece (Untitled,1967)[24] that Morris cited still had an underlying formal structuring—one that may not have been imposed by the artist, but certainly emerged during the process of arranging and laying out the clean-cut pieces of dangling industrial felt.[25] Secondly, he took theoretical issue with Morris’s whole idea of anti-form: “The nonformal alternative is no less formal than the formal enemy. […] Literal nonform, like chaos, is impossible,” as our brain only allows for patterned responses.[26] Though we may have cultural preferences for one kind of pattern to another, “both are equally formal.”[27] “The notion of an antiform may now mean only antigeometry, a rephrasing of formlessness that preoccupied the ancients from the Egyptians onwards.”[28] It was as if Morris were subscribing to a view, current in art circles of the time, that the form realized in non-representational abstract art was generally geometrical in character, and that a departure from such geometric structuring constituted a shift to the informal or non-formal. Morris would certainly have recognized that the gestural fluidity of previous Abstract Expressionist painting such as De Kooning’s represented a kind of informal abstraction—“art informel” as its European equivalent was often called—but he was trying with his more rigorously process-oriented work using everyday matter rather than paint to radicalize the “informal” to the point of being anti-form. Kaprow’s point was that such work was still located within a dialectic between the geometric and the non- or anti-geometric that had taxed artists ever since an art consciously shaped by formal convention and framing had emerged in antiquity.

Kaprow’s critique of Morris’s notion of anti-form was in part clearly motivated by his own claims to be recasting the basis of even the most radical recent art by fashioning happenings that took on a non-art life of their own outside any gallery context (within which work such as Morris’s felts were still being displayed). This, in his view, was the only way to make a clear departure from the conventional formal procedures within which even the most radical forms of recent modernist or avant-garde experimentation were still framed. Happenings, as exemplars of such non-art, however, still inevitably had form, as did any phenomenon in the process of becoming a focus of conscious attention, but realized in a different register from that found in conventional art. It was form literally embodied in the shapes of phenomena and patterns of motion or behavior existing in the everyday world. In such work, “the only form a thing has is what it looks like or does… that is if a chicken runs, eats chicken feed, and roosts, that is the only composition required.”[29] Composition becomes an operation inherent in the materials (including people and natural phenomena) incorporated in the art work and “indistinct from them.” Thus, the “materials and their associations and meanings… generate the relationships and movements of the Happening instead of the reverse.”[30] This sounds a little like a recasting of the modernist idea of truth to materials. Furthermore, in specifying the procedures guiding his non-art practices, he was obliged to talk in terms of patternings that had an internal logic of their own, and that did not completely blur into the fabric of the everyday material world. For example, in comments he prepared for participants in the happening Household, which he staged in 1964, he explained how its “performed phantasy, whose actions are direct, yet embodied in images of intense emotional pressure” required “a structured arrangement, which alone determines and sustains the degree of ‘pressure’ in the images.”[31]

He stopped short though of addressing the paradoxes his position entailed, paradoxes that, even as they seemed to compromise his conception of a radical non-art, energized his more suggestive art and writing. Implicit in much of his finest earlier critical writing is the coexistence of a radical renunciation of orthodox modernist formalism with an underlying commitment to certain aspects of modernist notions of form. This sits uneasily with any designation of his notions of experimental artistic procedure as anti-modernist in any straightforward way, or even as completely abandoning the structuring formal ambitions of a modernist art in the way that later postmodernists generally sought to do.

Avant-Garde

In his earlier writing, Kaprow envisaged the new experimental art as an avant-garde[32] driven by urgent ethical and existential imperatives. As he put it in the conclusion to the essay incorporated in his 1966 book Assemblage Environments and Happenings, “at present any [true] avant-garde art is primarily a philosophical quest and a finding of truths, rather than purely an aesthetic activity.”[33] Happenings, he stressed, like other genuinely radical initiatives of the time, were not just “another new style. Instead, like American art of the late 1940s, they are a moral act, a human stand of great urgency, whose professional status as art is less a criterion than their certainty as an ultimate existential commitment.”[34] In the analysis of recent “Experimental Art” he published in Art News in 1966, he explained how, for the genuinely experimental artist, “like the extremist or radical, being at the outer limits is an important condition for jarring into focus attention to urgent issues.” Such issues, he insisted, were “philosophical rather than aesthetic. They speak to the questions of being rather than to matters of art.”[35]

There was furthermore a romantic dimension to Kaprow’s abandoning any semblance of object-likeness in favor of the event-like ephemerality of the happening. It is “the one art activity,” he maintained, “that can escape the inevitable death by publicity to which all other art is condemned.”[36] Existing not as “a commodity, but a brief event, it may become a state of mind. […] It may become like the sea monsters of the past or the flying saucers of yesterday. […] As the myth grows on its own, without reference to anything in particular, the artist may achieve a beautiful privacy, famed for something purely imaginary while free to explore something nobody will notice.”[37] This condition of “beautiful privacy” was in a way a return to a very romantic conception of artistic autonomy, the fantasy of an art of unsullied interiority, free from the contamination of art’s means of public consumption and distribution. Still, he was acutely aware that a work, in order to exist, had to “enter the world,” even if only amongst the small group of people who were privileged to witness or participate in it. Divested of permanent material embodiment, however, how could the work persist in any meaningful way?[38] The myth surrounding or emanating from an ephemeral work only had a substantive afterlife if it could claim some form of ongoing public notice, even while being experienced as it were in “beautiful privacy,” both by the artist and the work’s audience, the latter including participants at the original event, and others who got to know the work by hearsay and possibly through a few fragmentary surviving documents.[39] The situation created a dilemma for critical evaluation that Kaprow himself recognized. In a crucial passage in his essay 1966 essay on “Experimental Art,” one can see him attempting to negotiate the dilemma while in the end having to fudge it:

Judgement may be difficult—often artist and public are enmeshed in a situation that will vanish after its enactment—but the context demands criticism in retrospect. If something of value must remain for our tomorrow, it will have to be a myth.[40]

An artwork cannot exist without a public; otherwise it is destined to become extinct immediately after its moment of realization. The paradox is nicely encapsulated in the title of an article Kaprow published in Artforum in 1966, “The Happenings are Dead: Long Live Happenings!”, ironically perhaps shortly before happenings began to go out of fashion as a widely recognized form of experimental art. Kaprow’s subsequent attempts to get around the dilemmas posed by claiming a public presence for his happenings by shifting his practice from overtly public performance to activity enacted in an ever-more intimate sphere meant he had to abandon the larger ambitions of the projects on which he had embarked at the beginning of his career.[41]

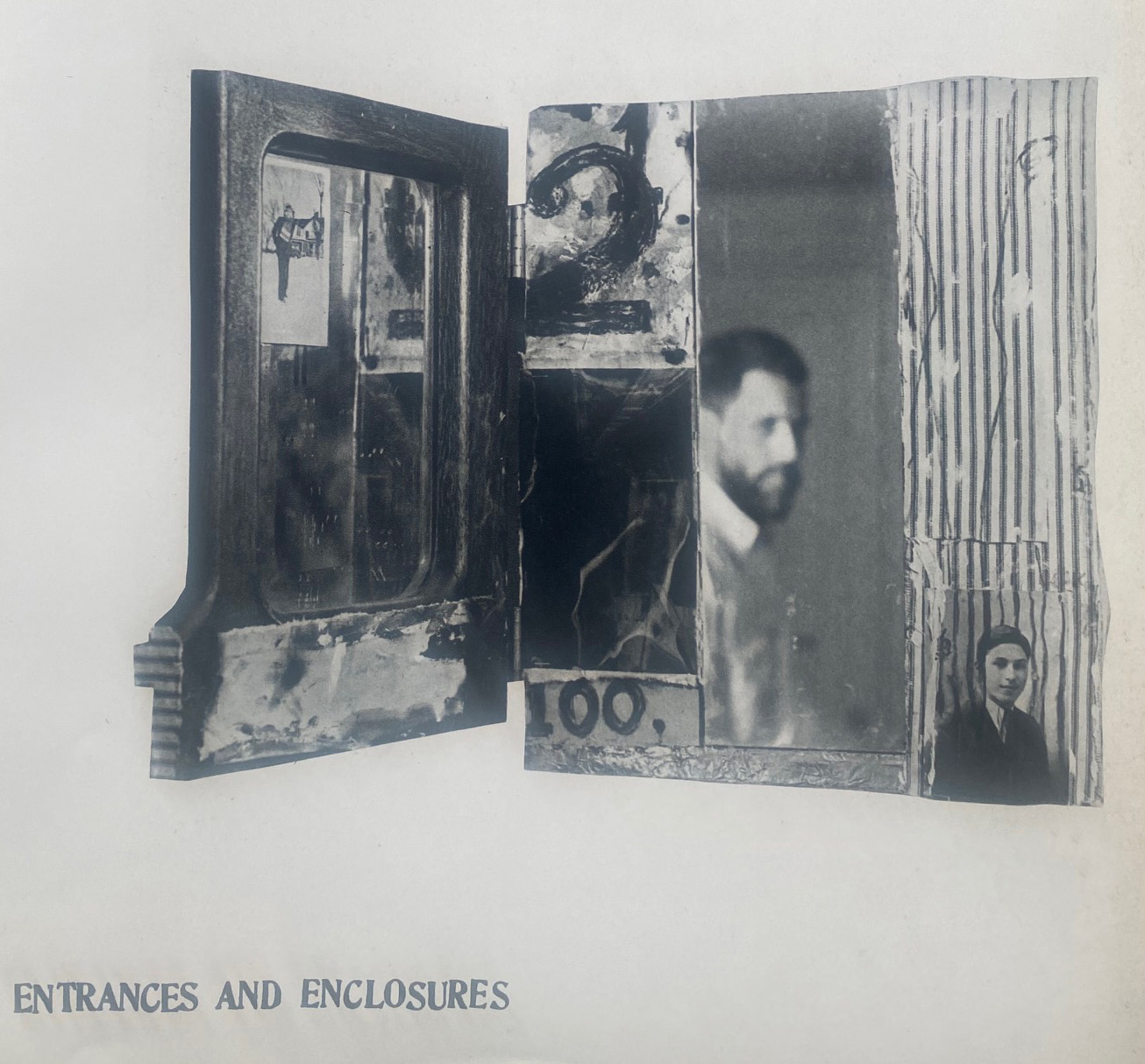

1. Illustration in: Allan Kaprow, Assemblage, Environments & Happenings (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1966).

Paralleling this, a marked change is also evident in the general tenor of his conception of new avant-garde art from the late 1960s onwards, broadly speaking from the agonistic to the therapeutic. In a manifesto, “The Demiurge,” that he published in 1959, the tone is almost Nietzschean: “I am convinced that the only human ‘virtue’ is the continuous rebirth of the Self. And this is what the new art is. […] As an artist it means living in constant spiritual awe and inner disequilibrium… It means casting our values (our habits) over the edge of great heights, smiling as we hear them clatter to pieces down below like so much crockery… I am ruthlessly impatient with anything I seriously attempt which does not shriek violently out of the unknown present.”[42] In a much later apologia for a life-like avant-garde art, his essay “The Real Experiment,” published in 1983, the self-fashioning involved is envisaged very differently: the artistic process involved is “therapeutic,” reconciling oneself to the normative conditions of everyday life (and by implication the everyday practice of art), in contrast to bringing one to the brink of their radical dissolution. Rather than challenging a settled self-awareness, the purpose is “to reintegrate the piecemeal reality we take for granted not just intellectually, but directly in experience. […] What is at stake now is to understand that of all the integrative roles lifelike art can play (for example, in popular entertainments, education, communications, politics, or social organization), none is so crucial to our survival as the one that serves self-knowledge.”[43]

Kaprow’s designation of the paradigmatic avant-garde artist shifts from Pollock, as the tormented and eventually tragic figure fated to live and die for the unsustainable intensity of his commitment to art, and Cage—deft, more Zen-like and laid back, his art equally expansive but divested of the “virulence,” “the sharp discontent” habitually associated with anti-formalism.[44] This shift is given an explicitly political inflexion in an essay, “The Artist as Man of the World,” published in Art News in 1964, that presents a summary overview of the changing complexion of the cultural politics of a radical modern art practice. Like many New York-based artist and critics, Kaprow adopted Rosenberg’s image of the more innovative artists of the immediate postwar period engaged in an intensely personal gesturing before the “abyss.”[45] In contrast to earlier modernist artists, “the lone artist did not want the world to be different, he wanted his canvas to be the world,” carried away by “the exhilaration of an adventure over depths in which he might find reflected the true image of his identity.”[46] The residual public politics of this agonism, still at odds with and resistant to its time, Kaprow explained, was abandoned by the following generation to which he belonged. Nowadays, the “modern artist… does not have the anxiety about ideological betrayals so typical of artist of the 1940s.”[47] A distinctive feature of the earlier modern avant-garde, unsettling the dominant values and conventions of the art world, was retained, but decoupled from any overt connection with broader public forms of social and political resistance. In so much as this was a new politics, it was one of a more personal nature.

A certain draining of public ambition is also evident in the trajectory of Kaprow’s artistic practice. His earlier happenings were scenarios or performative events that he envisaged as being evocative of or enacting some grittier material realities of his time.[48] He would, for example, maintain that he and his contemporaries’ use of “debris, waste products” in their earlier experiments had “a clear range of allusions with obvious sociological implications, the simplest being the artist’s positive involvement, on the one hand with an everyday world [“our ‘throwaway’ culture,” as he called it] and on the other with a group of objects which, being expendable, might suggest that corresponding lack of status which is supposed to be the fate of anything creative today.” At issue, too, in his view was the underlying philosophical conception of a “non-fixed, organic universe” in a state of “constant metamorphosis.”[49]

Not at any point in his career did Kaprow present himself as someone who envisaged his artistic radicalism as representing an overtly public political stand, let alone commitment to anti-capitalism or anti-consumerism. At the same time, he was quite astute about the larger shifts brought about by the American neo-avantgarde in understandings of the political complexion of a radical artistic practice and the associated persona of the radically experimental artist. It is instructive to compare him in this respect with a writer of an earlier generation of markedly different political background, who began as a committed Marxist, but for whom, as for Kaprow, Abstract Expressionism loomed large as a point of reference for understanding the formal and the ethical/political imperatives of radical artistic practice in postwar America. The art historian and critic Meyer Schapiro was someone whose conception of radical abstraction in modern art played a formative role for Kaprow when the latter was studying with him and attending his lectures in the 1950s. That they diverged in their evaluation of the changes effected by the neo-avantgarde in configuring a radical modern art and in the ethos of a radical artistic practice was almost inevitable given their generational difference and their very different political and cultural formation. At the same time, the differences as well as the convergences in the ways in which they tracked larger shifts in the ethical/political complexion of the art of the postwar period do bring into focus certain implications of such changes.

In Schapiro’s writings one can detect a significant change of outlook from a prewar, explicitly politicized take on earlier non-representational modern art practice to a more apolitical one in the immediate postwar period when he was teasing out the issues at stake in the new Abstract Expressionist painting.[50] There is a marked contrast between Schapiro’s political and social historical grounding of early modernist abstraction in the 1937 article “Nature of Abstract Art” and his later analysis of the ethos of postwar American Abstract Expression-ism in the essay dating from 1957, variously titled “Recent Abstract Art” or “The Liberating Quality of Avant-Garde Art.”[51] In the earlier essay, as in his writing from the period on Romanesque sculpture, close formal analysis is grounded in and complemented by extensive consideration of cultural and political developments in the society of the time that shaped the distinctive meaning these forms would have had. He was in many ways an exemplary historical materialist in his approach as an art historian and art critic. The later essay on the new radical abstraction of the American postwar “avant-garde,” as he calls it, gives up on any such publicly grounded political ambitions and instead represents radical formal experimentation as having an ethical significance in its own right. The struggle and conflict registered in such work is seen as being driven by, in Schapiro’s words, as “an affirmation of the self, or certain parts of the self, against devalued social norms,” an ethic in some ways in tune with the dominant Cold War cultural mind set of postwar America, and that has affinities with Harold Rosenberg’s Existential championing of this art. Still, there are residues of his previously much more explicit left politics in his characterization of the situation against which the artist is seen to be struggling, even as the art itself is prized primarily for exhibiting “the presence of the individual, his spontaneity and the concreteness of his procedures.” “If the painter cannot celebrate many current values, it may be that these values are not worth celebrating… the artist must cultivate his own garden as the only secure field in the violence and uncertainties of our time.”[52]

There is something of Kaprow’s later artistic self in the idea of the artist cultivating his own garden. However, Kaprow’s fascination with features of contemporary consumer culture, as well as the lengths to which he went in distancing himself from the ambitions associated with the pursuit of a strenuously focused painterly practice and of the values both aesthetic and non-aesthetic to which such a practice laid claim, take one out of the world that Schapiro inhabited. Even in his less Marxist postwar moment, Schapiro’s vision of a modern avant-garde retained vestiges of an older politics of resistance, though now severed from the communist cause that had inspired him back in the 1930s. Kaprow’s critical writing and art practice was symptomatic of an ongoing commitment to an idea of avant-garde experimentation, but increasingly removed from a larger world of publicly-engaged politics. His shift from the modernist association of radical formal innovation with a broader politics of opposition and resistance, let alone revolution, is in many ways truer to the temper of his times in Cold War New York than Schapiro’s ongoing loyalty to an agonistic conception of radical artistic experimentation.[53] An older avant-garde urgency was giving way to a post-avant-garde ethos more sequestered within concerns particular to the art world, regarding the formation of a critically self-aware art practice (and “critique” as it is often called) and the challenges such work might offer to normative conceptions of the work of art. Duchamp largely displaced the revolutionary or tormented artist-figure as model.[54] The production of vital politically-charged art continued, but no longer as critics like Schapiro might have wished, bound up in some way with the larger revolutionary ambitions previously associated with an avant-garde or modernist reconfiguring of artistic form.[55]

- [1] This article originated in research done for the discussion of Kaprow’s early happenings and critical writing in my book: Alex Potts, Experiments in Modern Realism: World Making, Politics and the Everyday in Postwar European and American Art (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2013), 13–16, 338–61, and the article “Writing the Happening: The Aesthetics of Nonart,” in Allan Kaprow—Art as Life, ed. Eva Meyer-Hermann et al. (Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute, 2008), 20–31. The latter offers a wealth of documentary material relating to Kaprow’s happenings. Two recent scholarly monographs elaborate on some of Kaprow’s major early happenings and the cultural politics informing them: Robert E. Haywood, Allan Kaprow and Claes Oldenburg: Art, Happenings, and Cultural Politics (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2017) and Judith Rodenbeck, Radical Prototypes: Alan Kaprow and the Invention of Happenings (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2011).

- [2] The majority of these essays and articles are republished in Allan Kaprow, Essays on the Blurring of Art and Life (Berkeley, Los Angeles, and London: University of California Press, 2003). This is an expanded edition of a volume edited by Jeff Kelley that came out under the same title in 1993. All references here are to the expanded edition. Neither edition includes the extended essay on happenings and their genealogy that Kaprow’s included in his book Assemblage, Environments and Happenings (New York: Abrams, 1966), much of which consists of skillfully staged arrays of photographic illustrations of happenings and related works.

- [3] The articles by Benjamin Buchloh that have been formative in shaping current understandings of the neo-avant-garde as a tendency in postwar art are collected in his book Neo-Avantgarde and Culture Industry: Essays on European and American Art from 1955 to 1975 (Cambridge, MA, and London: MIT Press, 2003). The complex interrelationship between neo-avant-garde initiatives and the informal non-geometric painterly abstraction of the immediate postwar period from which they were ostensibly radically departing is addressed in: Potts, Experiments.

- [4] The current tendency in art historical writing to make a categorical distinction between the two, consolidated theoretically by Peter Bürger’s classic study Theory of the Avant-Garde, trans. Michael Shaw (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1984; a first edition had already appeared in German in 1974), rather belies the frequent interchangeability between the designations of modern, avant-garde, and latterly modernist in the period. Art that today would be categorized as modernist was often referred to as avant-garde at the time. Neo-avant-garde is a retrospective designation.

- [5] The use of terms such non-form or formless does not necessarily mean a categorical abandonment of the idea of form, particularly in theoretical writing on art that came out of the American art world, where a lingering loyalty to a Greenbergian formal rigor often persisted within outspoken critiques of stale and restrictive formalist convention. Poststructural and ostensibly postmodern dismissals of modernist formalism are often not anti-form so much as critical of ossified formalist tendencies in mainstream writing about modern art, and committed to unsettling orthodox artistic convention, as were many modernists. One of the authors of the publication Formless, a User’s Guide (New York: Zone Books, 1997), Yve Alain-Bois, is undoubtedly a superbly rigorous critical analysist of artistic form, and much the same could be said of his coauthor, Rosalind Krauss.

- [6] This might be said of Kaprow’s article “Happenings in the New York Art Scene” (Art News, 1961), an early manifesto of the happening as an art world phenomenon as well as a discussion of the artistic/cultural context out of which it emerged (Kaprow, Blurring, 15–26).

- [7] Kaprow, Blurring, 27–45.

- [8] Ibid., 28.

- [9] Ibid., 28. Emphasis in the original.

- [10] The work by Barnett Newman he singles out is Vir Heroicus Sublimis (1950-51, Museum of Modern Art, New York).

- [11] Kaprow, Blurring, 40

- [12] Piet Mondrian, Compositon 2, 1922, oil on canvas, 55.6 x 53.3 cm., Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York.

- [13] Meyer Schapiro, “Mondrian,” in Modern Art: 19th and 20th Centuries (London: Chatto & Windus, 1978), 243, 256. Though only published in 1978, this paper’s “essential points,” as Schapiro makes clear (p. 258), “go back to lectures on Mondrian and other abstract painters” in courses he had been giving at Columbia University since the late 1930s, and which Kaprow would have attended. Schapiro was not a prolific publisher. The impact of his ideas on modern art in the New York art world of the 1940s and 1950s came by way of lectures he gave, rather than publications.

- [14] Kaprow, Blurring, 31, 33.

- [15] Ibid., 37.

- [16] Ibid., 33.

- [17] Ibid., 34.

- [18] Jackson Pollock, Number 32, 1950, enamel on canvas, 457.5 x 269 cm., Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, Düsseldorf, Germany.

- [19] Kaprox, Blurring, 39.

- [20] Ibid., 40. The last passage quotes Thomas B. Hess, editor of Art News, and author of the influential book on the new American abstract painting, Abstract Painting: Background and American Phase (New York: Viking Press,1951).

- [21] This argument was developed most fully in Kaprow‘s early “manifesto” essay “The Legacy of Jackson Pollock” (Art News, 1958). This includes a very acute and appreciative formal analysis of Pollock’s reconfiguring of painterly abstraction (Kaprow, Blurring, 3–6).

- [22] Kaprow’s essay, titled “The Shape of the Environment,“ published in Artforum in summer 1968 (Kaprow, Blurring, 90–94), responded to claims Morris made for his new felt work—including the piece Kaprow analyzed in detail (Untitled, 1967)—in his article “Anti Form,” published in Artforum earlier that year; Robert Morris, Continuous Project Altered Daily: The Writings of Robert Morris (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1993), 43–47.

- [23] In a series of articles published between 1966 and 1969 titled “Notes on Sculpture,” Morris tracked in detail shifts taking place in his art and his conceptualizing of it between his earlier geometric Minimalist sculpture to his most recent supposedly anti-form process-based work.

- [24] Robert Morris, Untitled, 1967, felt, variable dimensions, Sam Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

- [25] Kaprow, Blurring, 90–92.

- [26] Ibid., 93.

- [27] Ibid., 90.

- [28] Ibid., 93.

- [29] Ibid., 77. The passage comes from the article “Experimental Art,” published in Art News in 1966.

- [30] Kaprow, Assemblage, 198.

- [31] Allan Kaprow papers, box 9, folder 1, Getty Research Institute.

- [32] Late in his career he came up with the formulation “life-like avant-garde” (Kaprow, Blurring, 203).

- [33] Kaprow, Assemblage, 207.

- [34] Kaprow, Blurring, 21.

- [35] Ibid., 69.

- [36] Ibid., 59.

- [37]Ibid., 26.

- [38] Ibid, 53–54

- [39] For more details see: Potts, Experiments, 338–339, and Kaprow, Blurring, 62.

- [40] Ibid., 79.

- [41] A turning point in Kaprow’s ambitions to create happenings that had a significant public presence came in the late 1960s, in the wake of the failure of a particularly elaborate three-day televised happening, Gas, staged in 1967 at a beachside resort in East Hampton on Long Island. For this event, he and collaborators worked in cooperation with Dawn Gallery and WCBS-TV. Haywood, Allan Kaprow, 92–97.

- [42] Kaprow, “The Demiurge,” The Anthologist, spring 1959, 16. I am grateful to Robert Haywood for alerting me to this publication.

- [43] Ibid., 206, 217.

- [44] Ibid., 160.

- [45] Ibid., 47. Kaprow was referencing Harold Rosenberg’s landmark essay “The American Action Painters,” first published in Art News in December 1952, and republished in Harold Rosenberg, The Tradition of the New (New York: Viking Press, 1959), 23–39.

- [46] Kaprow, Blurring, 50.

- [47] Ibid., 50.

- [48] On the role played by such “realist” tendencies in Kaprow’s earlier happenings, see: Potts, Experiments, 34–352, 355–61.

- [49] Kaprow, Assemblage, 168–69.

- [50] On Schapiro’s earlier Marxist commitments and how these informed his evaluation of the role played by the social and political in modern art, see: Andrew Hemingway, “Meyer Schapiro and Marxism in the 1930s,” Oxford Art Journal, vol. 17, no. 1 (1994), 13–29, and also “Meyer Schapiro on the ‘Content’ of Impressionism: The Standpoint of Subjective Freedom,” Oxford Art Journal, vol. 46, no. 2 (2023), 291–304.

- [51] Meyer Schapiro, “Nature of Abstract Art” (first published in Marxist Quarterly in 1937), in Meyer Schapiro, Modern Art: 19th and 20th Centuries, 185-211, and “Recent Abstract Painting” (first published in Art News in Summer 1957 under the title “The Liberatory Quality of Avant-Garde Art”), ibid., 213–26.

- [52] Schapiro, Modern Art, 217, 222, 226.

- [53] In his contribution to this volume, “Meyer Schapiro’s Obsolescence: New York and the Portents of Postmodernism,” C. Oliver O’Donnell details Schapiro’s unresponsiveness to then-recent neo-avantgarde work and his ongoing attachment to Abstract Expressionism as a particularly significant modern cultural formation (one in which, as he put it, “the contradiction between the professed ideals and the actuality is most obvious and often becomes tragic” (Schapiro, Modern Painting, 224). Importantly, O’Donnell also shows how Schapiro on occasion would take an open view of recent forms of artistic experimentation that more conservative contemporaries rejected out of hand. His monograph on Schapiro—Oliver O’Donnell, Meyer Schapiro’s Critical Debates: Art Through a Modern American Mind (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2019)—had a different set of priorities, examining Schapiro’s broader intellectual formation and his approach to art historical scholarly inquiry. As such, it only makes brief mention, where appropriate, of Schapiro’s critical writing on the art of his own time (27–28, 121–22, 171–73). He does however comment on the role Schapiro possibly played in forming the thinking of a younger generation of artists, most notably Allan Kaprow and Donald Judd, both of whom studied under him (5, 171).

- [54] Kaprow contributed a tribute to Duchamp titled “Doctor MD” to the catalogue of the landmark Duchamp exhibition held at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, in 1973 (Kaprow, Blurring, 127–29).

- [55] With the poststructural turn taken in the 1980s and 1990s in critical and theoretical writing about modern art by figures such as Rosalind Krauss, one central task of a radical or critical art became that of exposing the enmeshment within the larger logic of late capitalist culture of modernist or avant-garde procedures and innovations previously seen as potentially liberatory. This marks a significant departure from Schapiro’s views and values. Interestingly, Schapiro played a significant role in Krauss’s early intellectual formation and her professorship bears his name.