The Global Circulation of a Black Radical Icon: George Jackson, the French Intelligentsia, and the Outlaw Class

In 1971 the French novelist and playwright Jean Genet issued a statement titled “Appel pour un comité de soutien aux militants politiques noirs emprisonnés” calling for the immediate release of all “détenus politiques” (political prisoners), including George Jackson, John Clutchette, and Fleeta Drumgo, collectively known as the Soledad Brothers.[1] Using the rhetoric of Black Power, the statement denounces “le système judiciaire raciste” (the racist judiciary system) and draws attention to state repression against Black militants.[2] Genet used his connections to the French intelligentsia to mobilize support for Black militants in France and was able to get a number of French intellectuals to sign his statement, including Roland Barthes, Maurice Blanchot, Julia Kristeva, Pierre Guyotat, Jacques Derrida, Marguerite Duras, Phillippe Sollers, and many others.

To understand how George Jackson and the Soledad Brothers became a cause célèbre among the French intelligentsia requires an examination of Jean Genet’s relationship to the Black Panther Party (BPP) and the post-May ’68 political climate in France. Genet’s contact with the BPP began on February 20, 1970 when Black Panther International Coordinator Connie Matthews (and possibly one other BPP member) solicited Genet for help in Paris.[3] According to Genet, he left France for the United States the next day, clandestinely entering the country through Canada because the US had always denied his visa requests. Recounting this event in an interview with Michèle Manceaux, Genet said:

Two members of the Black Panther Party came to see me in Paris and asked me what I could do to help them. I think that what they had in mind was that I would help them in Paris, but I said, “The simplest thing would be to go to America.” This answer seemed to surprise them a little. They said, “In that case, come. When do you want to leave?” I said, “Tomorrow.” They were even more astonished, but they reacted immediately: “Okay, we’ll come by to get you.”[4]

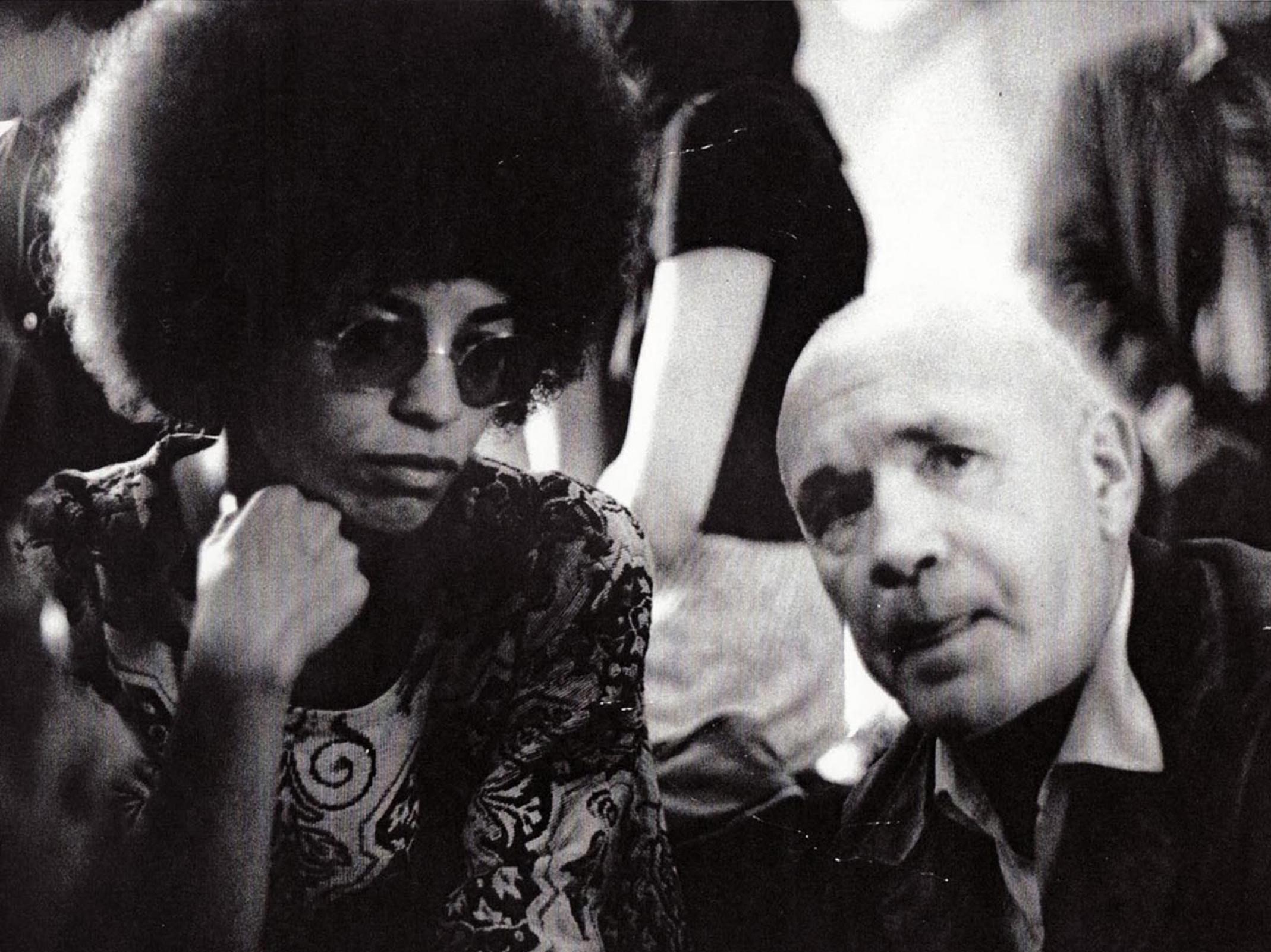

While in the US Genet spent two months with the BPP giving talks at universities and other venues in support of Bobby Seale and the Panther 21, who were later condemned and purged by BPP Chairman Huey P. Newton. Though Genet knew little English, he was assisted by translators (including Angela Davis, who majored in French as an undergraduate) and was able to get by exchanging written notes with David Hilliard, the BPP Chief of Staff who accompanied Genet during much of his travels in the US. It was Genet who introduced French philosopher Michel Foucault to the BPP, and Genet who can be credited with bringing Jackson’s collection of prison letters, Soledad Brother, to the French-speaking world. In an essay about the relationship of the French activist organization Groupe d’Information sur les Prisons (GIP) to prison movements in Italy, Great Britain, Sweden, and the United States, Philippe Artières writes, “En France, ce mouvement noir americain est connu par les traductions, tres rapides, des differents ouvrages des leaders noirs et par les textes de Jean Genet” (In France, the movement of Black US Americans became known through the rapid translations of the works of Black leaders and through the texts of Jean Genet).[5] While even today important works of French political theory may take a decade or more to reach the US, books by Black radicals such as Malcolm X and Stokely Carmichael were published in French almost immediately after they were published in English. Between 1969 and 1972, French editions of a number of works by Black Panthers were published, including three titles by Eldridge Cleaver (Un Noir à l’Ombre, Panthère Noire and Sur la Revolution Amiricaine), Bobby Seale’s À L’Affût, two books by Angela Davis (Angela Davis Parle and S’Ils Frappent à l’Aube), two books by George Jackson (Devant mes Yeux la Mort and Les Frères de Soledad) and the collection Les Panthères Noires Parlent.[6]

Jackson’s circulation in France is particularly striking because Jackson spent all of his adult life in prison after he was given a one year to life indeterminate prison sentence in 1961 for an armed robbery of $70 at a gas station. Thus, Jackson was unable to physically travel, unlike many of the other Panthers published in France. Angela Davis, for instance, served as Genet’s translator while he was in the US and was connected to a cosmopolitan intellectual network through her travels and academic studies in France and Germany. The brutal fact of Jackson’s confinement in Soledad and San Quentin and the global scope of his political consciousness, as well as the appeal of his writings to international audiences, is somewhat paradoxical. While in prison Jackson wrote Blood in My Eye, one of the most nuanced works of political economy produced by a Black Panther. While reading Blood in My Eye—and in particular the sections that flesh out his genealogy of fascism and analysis of the history of global capitalism—it is clear that Jackson’s political consciousness is not parochial and extends far beyond his lived experiences in prison. Not only was Jackson influenced by global events, but he also had an influence on global politics. How did Jackson come to know the world, and how did the world come to know Jackson? How did Jackson’s theorizations of capitalism and the “prisoner class,” made from within prison, materially and symbolically circulate in the world? This essay deals specifically with Jackson’s influence on the French intelligentsia, which was enabled by Genet’s relationship with the BPP.

Not only were Jackson’s ideas and struggle taken up by people around the world, but his assassination also created a ripple effect, setting off a wave of prison revolts in the US and abroad. The Attica revolt at the Attica Correctional Facility in Attica, New York began on September 9, 1971, two weeks after the assassination of Jackson at San Quentin. But Attica was only the beginning of a surge of prison revolts that happened around the world. In France in particular, there was a wave of prison revolts that took place from late 1971 to 1972. Around a week after Governor Nelson Rockefeller sent troops to storm and put down the rebellion at Attica, a similar—although much smaller—revolt took place in France at Clairvaux Prison. On September 21, 1971 two prisoners—Claude Buffet and Roger Bontems—took two hostages and demanded their release. Officers stormed Clairvaux the next day, and the two inmates were guillotined in June 1971. The following day US newspapers ran an Associated Press story about the wave of revolts catalyzed by Attica. In the Sarasota Herald Tribune, the revolt at Clairvaux was mentioned. The article noted that a French newscast said, “After Attica, an identical affair has occurred in France.”[7] To understand how and why Black radicalism and prisoner struggles in the US had such a major influence in France it is necessary to examine how the political climate of France around the events of May 68 was shaped by Black radicalism in the US.

The Black Panthers and the French Intelligentsia

[Jean-Luc Godard] was convinced that America was about to burst into revolution like the student uprisings in France in 1968. He kept saying we have to hurry and get to California because this is where it is going to begin. I asked, ‘‘What was going to begin?’’ ‘‘The revolution you fool,” he told me.

—D.A. Pennebaker on his Panther-inspired collaboration with Godard[8]

There will be a fight. The fight will take place in the central cities. It will be spearheaded by the blacks of the lower class and their vanguard party, the Black Panther Party.

—George Jackson, Blood in My Eye[9]

Even before Jean Genet popularized the writings of George Jackson and galvanized the French intelligentsia into supporting the cause of the Soledad Brothers, French artists and intellectuals were already beginning to look optimistically to Black radicals in the US for political inspiration after the uprisings of May 68 failed to bring about a revolution in France.[10] In 1968 two French New Wave filmmakers produced films featuring the Black Panther Party: Jean-Luc Godard’s Sympathy for the Devil and Agnès Varda’s documentary Black Panthers. Following May 68, Godard—who believed American was going to explode into revolution—rushed to the US to work on a film with American documentary filmmaker D.A. Pennebaker. The film was to be titled One A.M. (One American Movie). The filmmakers interviewed American radicals Tom Hayden and Eldridge Cleaver, but Godard eventually abandoned the project upon realizing he had misjudged the revolutionary situation. Speaking about his abandonment of the project in a 1970 interview he said, “It is two years old and completely of a different period. When we shot that I was thinking like a bourgeois artist.”[11]

Why were French leftists enamored with Black radicals? According to Beth Mauldin, French intellectuals and leftists turned to Black radicals because they 1) felt the student uprising in France was similar to the struggles of urban US Blacks, 2) wanted to disidentify with bourgeois white society, 3) believed that Black Americans living in the heart of empire were well-positioned to jump-start the revolution, and 4) had grown disillusioned with traditional Marxism. Mauldin writes:

In an interview for The New York Times just weeks after Robert Kennedy’s assassination, Romain Gary, French novelist and husband of American actress Jean Seberg, commented on the similarities between the student-worker rebellion in France and the Black uprisings in urban ghettoes across the United States. As he and other intellectuals noted, French radicals were adopting and adapting the techniques and slogans of their American counterparts, but not necessarily their peers. Rather than emulating Students for a Democratic Society, many French student activists were enthralled by the Black Panther Party (BPP). “The average French student wants to identify with the Negro in the American ghetto. It was no accident that the radicals at the Sorbonne barricades adopted the slogan of ‘student power’ from the black nationalist cry of ‘black power.’”[12]

French intellectuals who felt marginalized by French society, such as Varda and Genet, identified with the BPP’s outsider status. Speaking about the BPP, Varda said in an interview that, “The Black Panthers were the first to say, ‘We want to make the rules, the theory.’ And that’s what made me aware of the woman situation. A lot of good men had been thinking for us. Marx did. Engels did … Yet maybe we need to be through with Marx, for Marx doesn’t give the keys and answers for us women.”[13] For Varda, the BPP’s attempts to theorize their situation for themselves enabled her to become conscious of her own situation as a woman.

For French intellectuals, American radicalism contained an originality and vibrancy that helped them think through their own situation and inspired them to break with traditional Marxism. French intellectuals such as sociologist Jean-Francois Revel felt that “traditional Marxist ideas of revolution were no longer applicable within a postindustrial, globalizing economy.”[14] Revel wrote that, “Revolution is not a settling of accounts with the past, but with the future. American revolutionaries sense this; and that is the reason for America’s originality in comparison to Europe.”[15] It was Black radicals in the US who were theorizing the effects of the automation of production on the working class, the significance of global anti-colonial struggles, the effects of global finance on national sovereignty (articulated in Huey Newton’s theory of reactionary intercommunalism), and the new forms of revolutionary struggle that would be required to bring about a revolution (for the BPP: urban guerrilla warfare). In a sense, the Panthers were the avant-garde of post-Marxist theorizations of the new world order. In the early 1970s Black radicals such as Jackson would also theorize the function and significance of prison as an institution, which would have profound effects on the French intelligentsia. It was Jackson’s status as a prisoner that initially attracted the attention of Genet, who went on to popularizeJackson’s collection of prison letters, Soledad Brother.

Not only was Jackson “consumed” by weary French intellectuals looking to enliven themselves with the no-holds-barred discourse of Black radicalism, but Jackson was also “consuming” the literature and ideas of the Francophone world. Among the ninety-nine books in Jackson’s library at the time of his assassination, Francophone authors include Malraux, Fanon, Sartre, Camus, Césaire, and others. Indeed, much of Jackson’s thinking on urban guerrilla warfare and foco theory in Blood in My Eye was also influenced by the French intellectual Régis Debray’s Revolution in the Revolution.

“I am a black whose skin happens to be white”: Genet’s Encounter with the BPP

The Panthers accepted me as I am.

—Jean Genet in an interview with Michèle Manceaux[16]

On May 7, 1970 Genet returned to France, by way of Canada, after spending two months with the Black Panthers. In France and while traveling abroad he continued to lend his support to the Panthers as well as US prisoner struggles. Months after Genet left America, Angela Davis became an international cause célèbre after she was charged with aggravated kidnapping and first degree murder because a gun that was used by Jonathan Jackson (little brother of George Jackson) to take hostages at the Marion County courthouse was registered in her name. Genet publicly defended Davis and the Soledad Brothers in his article “Angela and Her Brothers,” which condemns media representations of Davis and the BPP. To combat the media’s demonization of Davis, Genet paints a warm and personal portrait of Davis, describing her as “incontestably the most persuasive, the warmest, and one of the most intelligent” members of the Soledad Defense Committee.[17] In order to demystify the Panthers and challenge sensationalist representations of them Genet discusses their politics and the context from which they emerged.

Though Genet’s engagement with the BPP lasted only a few years, it could hardly be called superficial. In addition to his tour of the US speaking on behalf of the BPP, Genet wrote a number of articles on the Panthers that were published in France and the US, four of which appeared in The Black Panther Intercommunal News Service, the official newspaper of the BPP. But Genet’s most well-known text on Black radicalism is the introduction to the first edition of Jackson’s collection of prison letters, Soledad Brother, published in 1970. According to historian Dan Berger, Jackson’s lawyer Fey Stender solicited Genet’s support in promoting the book not long before its publication.[18] In Genet’s introduction to the book, the main themes he uses to frame his discussion of Jackson include poetic genius, Black rage against the white world, and the “book” as a weapon. As Berger notes, “Genet’s contribution to Soledad Brother gave the book an instant, international literary imprimatur.”[19]

In my reading of Genet’s commentary on Jackson and the BPP there are two somewhat opposing points I want to emphasize. First, I argue that the interpretive framework Genet’s uses in his introduction to Soledad Brother essentially displaces and disappears Jackson himself. However, the rhetoric used by Genet in the introduction deviates from the rhetoric he uses in his articles on the Panthers, which suggests that Genet was being strategic in his presentation of Jackson’s project. Second, in my more generous reading of Genet, I argue that his identification with Jackson and the BPP is not as outlandish as it initially seems when one examines Genet’s writings through the prism of the outlaw class rather than race. As I show in my discussion of the BPP’s theorizations of the lumpen and the prisoner class, Jackson thought that revolutionaries were necessarily outlaws. Genet—as a former outlaw, thief, and prisoner—felt a kinship with Jackson based on their shared antagonistic relationship to society and law. While the “outlaw” may initially appear to be a subject position rather than a materially constituted class, Jackson’s conception of the prisoner class is rooted in the idea that the prisoner has a structural relationship to capital that is distinct from that of the exploited worker. Yet this material-based “identity” also functions as a counter-hegemonic ideological formation, a kind of radical subjectivity that aims to pull the subject out of the social order through the development of an antagonistic relationship to society as such. If, as Louis Althusser writes, the relations of production are reproduced through ideology and the interpellation of subjects as raced, gendered, and classed individuals, Genet and Jackson’s outcast inverts this process by becoming unmoored from their proper place in social reproduction and charting a line of flight.[20]

Upon an initial read, Genet’s introduction vividly appears to be more about Genet than Jackson himself. Genet’s musings on the relationship (or tension) between the poet vs. the revolutionary, material vs. symbolic action, the white vs. the Black world, and aesthetic vs. political forms of revolt actually say more about Genet’s personal preoccupations than Jackson’s. Initially, it seemed that Genet’s need to cast Jackson as a “poetic genius” was an attempt to make Jackson’s project palatable for white audiences, as it emphasizes the singular nature of Jackson’s literary talent and the universality of his insights (as Genet puts it: “a consciousness so acute that it will be valid for all men”).[21] Genet writes:

If we accept this idea, that the revolutionary enterprise of a man or of a people originates in their poetic genius, or, more precisely, that this enterprise is the inevitable conclusion of poetic genius, we must reject nothing of what makes poetic exaltation possible. If certain details of this work seem immoral to you, it is because the work as a whole denies your morality, because poetry contains both the possibility of a revolutionary morality and what appears to contradict it.[22]

Here, revolutionary subjectivity must be subsumed under the subjectivity of the poet. Moreover, there is a discrepancy between how Jackson identifies and how he is identified by Genet. In Blood in My Eye Jackson describes himself as a “revolutionary Marxist-Leninist-Maoist-Fanonist” while Genet chooses to identify Jackson as a poet above all else, even going so far as to assert that “poetic genius” is primary, and that the revolutionary enterprise emerges from poetic genius. What this rhetorical gesture essentially does is prioritize the aesthetic qualities of Soledad Brother over Jackson’s political analysis. Though Jackson is unarguably a talented writer, this exceptionalizing gesture creates an interpretive framework for the book that enables white audiences to identify with Jackson. The subjective experience of Jackson, as a revolutionary Black man inside prison, may be completely outside Jackson’s white readers’ sphere of understanding. By highlighting the work’s literary qualities Genet is essentially making the text intelligible to white readers by creating a way for them to engage the text. In a sense, it defangs the text by encouraging readers to approach it as a literary object rather than encouraging readers to engage Jackson’s challenging politics. However, given that the purpose of an introduction to a book is partly to prepare the reader for a text, Genet may have chosen to highlight certain aspects of Jackson’s work over others in order to create a bridge between Jackson and his readers. Genet seems hyper-aware of this potential gulf between Jackson and his audience when he writes, “A book written in prison—in any place of confinement—is addressed chiefly perhaps to readers who are not outcasts, who have never been to jail and who will never go there.”[23] However, even if this is the case, why should the confined person be forced to capitulate to the terms of the people on the outside?

There is nothing wrong with discussing the aesthetic qualities of Soledad Brother, but Genet’s framing of the book in this way is problematic insofar as he wrote the introduction in such a way that his own preoccupations masquerade as Jackson’s. While it is difficult to substantiate the claim that Genet projected his set of concerns onto Jackson, Genet’s interview with Michèle Manceaux, where he discusses his relationship to Jackson and the BPP, reveals that he did essentially graft his understanding of the relationship to writing and politics onto Jackson. For instance, for much of Genet’s career his engagement with politics was limited mostly to the aesthetic realm. He was more concerned with linguistic corruption as a political act than collective action. In the interview with Manceaux he noted that “[destroying society was a] concern that I had when I was very young, but I couldn’t change the world all alone. I could only pervert it, corrupt it a little. Which is what I tried to do through a corruption of language, that is, from within the French language, a language that pretends to be so noble.”[24] This personal preoccupation with the corruption of language is transferred directly onto Jackson and the figure of the Black prisoner in Genet’s introduction. He writes:

… the prisoner must use the very language, the words, the syntax of his enemy, whereas he craves a separate language belonging only to his people. Once again his situation is both hypocritical and wretched: he can express his sexual obsessions only in a polite dialect, according to a syntax which enables others to read him, and as for his hatred of the white man, he can utter it only in this language which belongs to black and white alike but over which the white man extends his grammarian’s jurisdiction. It is perhaps a new source of anguish for the black man to realize that if he writes a masterpiece, it is his enemy’s language, his enemy’s treasury which is enriched by the additional jewel he has so furiously and lovingly carved.

He has then only one recourse: to accept this language but to corrupt it so skillfully that the white men are caught in his trap. To accept it in all its richness, to increase that richness still further, and to suffuse it with all his obsessions and all his hatred of the white man.[25]

But who, after reading Soledad Brother, walks away feeling like Jackson felt particularly anguished about the fact he had to write his “masterpiece” in English? If anything, this is much more of a Black cultural nationalist concern than it is a concern of Jackson’s, though the book is suffuse with many passages where Jackson’s rails against western culture, particularly in his letters to his mother Georgia and his father Robert.[26] However, Jackson’s hatred of the white man is not so much aimed at his aesthetic propriety as it is at his institutions, though of course these institutions are legitimized through language and culture.

The BPP’s disdain for western culture and the white world is what initially drew Genet to the BPP. When Manceaux asked Genet in an interview why he feels that the BPP’s cause is also his cause he noted that what immediately made him feel close to them “was their hatred for the white world, their concern to destroy a society, to smash it.”[27] Here Genet reveals that he identifies primarily with the negative or destructive aspect of the BPP’s politics, rather than the constructive aspect, i.e., their political vision.

Genet’s disdain for the white world comes through in the damning, accusatory tone of the essay. However, condemnations of anti-Black racism, when written by a white person in a tone of righteous indignation, sometimes come across as self-aggrandizing, performative gestures that function to purify the conscience of the white author more than they do to elucidate an aspect of how racism operates. Genet sometimes falls into this trap; however, he is very much aware of the pitfalls that accompany white attempts to engage Black struggle, even when he is unable to avoid them. While Genet writes, in the essay “Angela and Her Brothers,” that he has “no confidence in liberals,” to whom he mockingly refers as “petition signers,” it was Genet who mobilized some of the most prominent figures of the French intelligentsia to append their names to a statement he wrote in support of the Soledad Brothers and all Black militants imprisoned in the US. It is impossible to know what material effect Genet’s symbolic support for Black militants and the BPP actually had, but Genet was critical of the very modes of engagement he utilized. The petition, as a mode of political engagement, is frequently a low-risk gesture that involves minimal effort. At its worst, it is an empty, self-congratulatory gesture that allows the signers to accumulate social capital by advertising which causes they support. Jacques Derrida, one of the French intellectuals who signed Genet’s petition of support for the Soledad Brothers, expressed reservations about the petition and his inclusion in an anthology on Jackson that Genet was editing at the time. In a letter to Genet, Derrida writes:

… if one denounces only a case or an affair … is there not a risk of closing up the wound of everything that has been broken open by the letters you presented, of reducing these enormous stakes to a more or less literary, or even editorial, event, to a French, or even Parisian, production that an intelligentsia, busying itself with its signatures, would have staged for itself? That is why I am still hesitant to participate in the collective action you described to me.[28]

In an article that discusses the philosophical implications of Derrida’s hesitation and Genet’s eager participation, Mikkel Bolt Rasmussen asks whether Derrida’s deconstructive (anti-)politics—while attuned to the ways in which engagement with the “other” can be a form of displacement—runs the risk of justifying political apathy, paralysis and non-engagement.[29] However, the article does not note that Genet made a very similar critique of symbolic and performative gestures that Derrida made in his letter. In Genet’s interview with Manceaux he distinguishes between “symbolic” and “revolutionary” actions in his discussion of how he thinks the American Left should relate to the BPP. For Genet, “symbols” merely refer to events or actions that have already taken place while “revolutionary actions” take direct part in the creation of something new, which is why “all revolutionary acts have about them a freshness that is like the beginning of the world.”[30] Genet goes on to say:

… a symbolic gesture or set of gestures is idealistic in that it satisfies the men who make it or who adopt the symbol and prevents them from carrying out real acts that have an irreversible power. I think that a symbolic attitude is both the good conscience of the liberal and a situation that makes it possible to believe that every effort has been made for the revolution. It is much better to carry out real acts on a seemingly small scale than to indulge in vain and theatrical manifestations.[31]

The interviewer, who comes across as somewhat skeptical of Genet’s positions throughout the interview, prods him on this point when she asks in her rejoinder: “What real acts did you carry out in the United States?” Genet replies:

I went from city to city, university to university, working for the BPP, talking about Bobby Seale and about the importance of helping the BPP. These lectures had two goals: to popularize the movement and to collect money. I went to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Yale, Columbia, Los Angeles, and so on. In this way, the most important universities opened their doors to the BPP.[32]

Is Genet’s act of metaphorically knocking down the iron gates of Ivy League and other prestigious institutions a revolutionary act, or does it risk turning the Black radical cause into a commodified, “revolutionary chic” image that can be consumed by mostly white students (presumably enthusiasts of French literature) who may have no stake in the cause Genet was promoting? Certainly Genet’s physical movement through space, when he traveled speaking on behalf of the Panthers, could be considered a material action. Money is also material, and fundraising is an essential part of the survival of any political organization. No doubt, the BPP were in dire need of support around this time, as the party was beginning to unravel due to state repression, internal power struggles, and the pressure the legal system was putting on the organization through the mass arrest of party members (often on trumped-up charges). However, if by Genet’s own definition a revolutionary act is that which takes part in the creation of something new, then Genet’s response essentially dodges the question he was asked.

The question regarding the distinction between material and symbolic acts returns again toward the end of the interview. Following a discussion of how Genet was able to communicate with the Panthers when he spoke very little English, Manceaux changes the subject and asks, “Would you have written The Blacks in the same way after living through what you just experienced?” Genet testily responds, “If you don’t mind, let’s not talk about my plays.”[33] Manceaux asks Genet if he is unwilling to discuss his plays because he no longer has an interest in writing. To this Genet responds, “I don’t think that Brecht did anything for communism, and the revolution was not set off by Beaumarchais’s The Marriage of Figaro. I also think that the closer a work of art is to perfection, the more it is enclosed within itself, Worse than that—it inspires nostalgia!”[34] Here, Genet’s response to Manceaux’s question reveals an existential anxiety on his part regarding the writer’s ineffectiveness when faced with the task of bringing about revolutionary social change.

In Genet’s condemnation of liberal “petition signers” and his offhand comment about Brecht doing nothing for communism, Genet makes a clear distinction between “material” and “symbolic” interventions, while elevating the former. However, Genet’s revolutionary bravado is mostly just rhetorical. While he condoned executing whites in his BPP speeches, he is much more tempered in the introduction to Soledad Brother. Here, he seems to resolve his anxiety about the writer’s inability to effect revolutionary change and the futility of the symbolic gestures of the liberal by elevating the symbolic to the level of material intervention. One way he does this is by characterizing the book as a weapon. He writes, “And from the first letter to the last, nothing has been willed, written or composed for the sake of a book, yet here is a book, tough and sure, both a weapon of liberation and a love poem.”[35] Though I personally agree with Genet that there are ways in which symbolic interventions are material, this rhetorical gesture seems more about Genet’s need to feel politically relevant as a writer than it is about Jackson’s project. Jackson himself maintains the distinction between weapon and literature when he writes, “We will build these communes against all resistance, the pamphlet in one hand, the gun in the other.”[36] For Jackson both the “pamphlet” (ideology) and the “gun” (force) are necessary tools to bring about a successful revolution, but Jackson doesn’t suggest that they are the same.

“We were never intended to be part of his world”: Jackson, Genet, and the Outlaw Class

Outlaws, of course, I thought. Revolution will not be tolerated, it is against the law in the totalitarian corporative state. The revolutionary must certainly reconcile himself with one day becoming an outlaw.

—George Jackson, Blood in My Eye[37]

Madeleine Gobeil: Why did you decide to be a thief, a traitor, and a homosexual?

Genet: I didn’t decide, I didn’t make any decision. But there are certain facts. If I started stealing, it’s because I was hungry.

—Declared Enemy[38]

We were never intended to be part of his world.

—George Jackson, Blood in My Eye[39]

In an article on Derrida’s letter to Genet on Jackson, Rassmussen writes that the most important thing for Genet was a kind of “artistic anarchism” that made “relentless freedom more important than any political programme or stance.”[40] As I have demonstrated in the previous section, there are many ways in which Genet projected his aesthetic concerns onto Jackson and resolved his own inner turmoil about the irrelevance of the writer to revolutionary struggles by using Jackson to elevate symbolic interventions to the level of material interventions. At a glance, Genet’s connection to Jackson seems superficial, and his identification with Jackson impertinent. However, while there are problems with how Genet framed Jackson in his introduction to Soledad Brother, his engagement with Jackson cannot be read as merely a self-serving performance of solidarity (which is how the introduction can feel upon an initial read).. Genet identified with Jackson not only because he was aesthetically transgressive in his rejection of white propriety, but because he felt a kinship with Jackson based on his experiences as a thief and a former prisoner. Until the age of thirty, Genet spent much of his life wandering across Europe going from prison to prison. He spent around seven years in prisons and reformatories.[41] Though it may seem somewhat misguided for Genet to put Jackson in the same lineage as the Marquis de Sade and Antonin Artaud—as he does in his introduction—Genet does so because, according to him, confinement as a material condition, whether it be in prisons or asylums, produces a certain aesthetic sensibility and disposition toward the world: a kind of outcast consciousness. In this sense, Genet’s project of constructing an “outlaw” lineage or class is not so unlike Jackson’s attempts to theorize the lumpen and prisoner classes. Though Genet’s valorization of literary “genius” reinforces a notion of individual talent that does not pay heed to Jackson’s radically anti-individualist conceptualization of himself as a subject, Genet’s comments about the “odor” of work produced in confinement suggests that consciousness is in part the byproduct of material circumstances. He writes:

But I have lived too long in prisons not to recognize, as soon as the very first pages were translated for me in San Francisco, the special odor and texture of what was written in a cell, behind walls, guards, envenomed by hatred, for what I did not yet know so intensely was the hatred of the white American for the black, a hatred so deep that I wonder if every white man in this country, when he plants a tree, doesn’t see Negroes hanging from its branches.[42]

In this passage, Genet performs two distinct gestures: one of identification and one of differentiation. He writes that upon reading Jackson’s text he could immediately recognize a text produced in confinement by its odor and texture. In other words, spatial confinement gives rise to texts that are irrevocably marked by the condition from which they emerge. But Genet is not so naive as to believe he can understand every aspect of Jackson’s subjective experience. What he could not yet understand upon first encountering Jackson’s prison letters was the way in which American racism shaped Jackson’s consciousness, and how hatred for Blacks shaped the consciousness of white America. When Genet wonders “if every white man in this country, when he plants a tree, doesn’t see Negroes hanging from its branches,” he is acknowledging that history directly shapes what one sees. Thus, both Genet’s identification with, and differentiation from, Jackson was partly based on a material and structural analysis of the role of prisons and history in shaping one’s consciousness.

Genet and Jackson’s discussion of the production of outlaw consciousness implicitly offers a theory of identity and subject formation that is pertinent to ongoing debates about ideology and the post-WWII cultural turn in Marxism. While culture was already theorized by the Frankfurt School, most notably in Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer’s analysis of the culture industry, it was during the postwar period that Marxists attempted to develop a rigorous theory of ideology. The debates were catalyzed by the emergence of the New Left, the theoretical interventions of structural Marxist Louis Althusser, and the founding of the field of cultural studies by thinkers such as Stuart Hall. Hall revived the works of Antonio Gramsci for the purpose of understanding the role of civil society, ideology, and culture in neutralizing revolt; in other words, by attending to the “superstructural” level of the social formation. What these thinkers sought was a theory that could account for capitalism’s stability: given its internal contradictions, why had the advanced industrial economies of Europe and the United States failed to undergo communist revolutions? Did it have something to do with the fact that the liberal democracies of the west have highly developed civil societies? What is the relationship between the (economic) base and the superstructure (civil society, the media, the state, ideology, etc)? How do these relatively autonomous domains of the social formation “articulate” or link up with each other? If class consciousness does not arise naturally from the worker’s experience as a laboring subject, then how should we think about identity and the creation of oppositional formations? Ultimately, these thinkers attempted to fill a gaping lacuna in Marxist theory; namely, the absence of a theory of the subject and identity formation. While a full account of these debates is beyond the scope of this article, Hall and Althusser’s accounts of subject formation are relevant to Genet and Jackson’s analysis of the prisoner class and outlaw consciousness.

Jackson and other members of the BPP had an analysis of prisoners and the lumpen as a distinct class that had distinct concerns and emerged from different material circumstances from those of the working class. As a former “criminal,” Genet probably identified much more with the lumpen experience articulated by the BPP than he did with the French bourgeoise. But what is significant about Genet’s identification is it reveals the ways in which Genet and Jackson share an antagonistic relationship to law and society. Genet did not only see in Jackson a fellow former thief, but someone who shared a similar social position. For Jackson, what distinguishes the lumpen class and prisoners from the working class is their exclusion from civil, social and economic participation. This distinction also reveals the difference between being exploited under capitalism (the worker) and being marked as superfluous to capitalism (the outcast).

While contemporary left critics of “identity politics” dismiss identity as an ideological tool used to fracture the working class and foreclose solidarity, Genet and Jackson’s outlaw identity is based on a material analysis of the outlaw’s relationship to capital. For both, the outlaw can function as an oppositional formation. The position of the outlaw does not represent a particular program or doctrine; rather, it is embodied in practices that have an antagonistic relationship to the social formation. If, as Althusser writes, ideology operates in and through us through a process of subjectivization and subjection—or interpellation—then Genet and Jackson attempt to short-circuit this process by refusing to occupy their proper places in social reproduction. The price Jackson paid for this posture of pure refusal was high: interminable incarceration and, ultimately, assassination. The state’s attempt to purge Jackson—both his life and his legacy—reveals that ideological state apparatuses (ISAs) are ultimately undergirded by repressive state apparatuses (RSAs); in this case, Jackson’s insubordination triggered the full force of the prison system, the RSA that superintends populations marked for social exclusion.

Paradoxically, it is social exclusion which produces the outlaw consciousness that Genet and Jackson view as ripe with revolutionary potential. Yet Jackson is also aware that the lumpen class may experiences a psychic anguish and sense of alienation that pulls them toward “anti-communal behavior” rather than political revolt and comraderie. He writes, “It is the sense of the finality of their exclusion from solid social-economic participation that forces our youth away from the crippled family unit into the streets. It causes the excessive importance of meaningless relationships and the prevalence of anti-communal behavior which is a psycho-social response to the loss of-and longing for-community.”[43]

To what extent did Genet suffer from this longing for community described by Jackson? Was Genet’s identification with Black Americans Genet’s attempt to find a surrogate family, a vision of kinship based, not on the nuclear family, but on a shared state of existential homelessness? In “Genet Politique, l’Ultime Engagement,” an article that discusses Genet’s political engagement and lifelong search for belonging, Natalie Fredette writes, “Genet est sans famille” (Genet has no family).[44] According to Fredette, though Genet claimed to find a “frère” (brother) in Jackson, Jackson was always already “un faux frère”: a false brother.[45] Though Genet said he identified most with “the oppressed of the color races, the oppressed who revolted against the whites” and claimed that he was “a black whose skin happens to be white, but … definitely a black,” Fredette notes that Genet never succeeded at fully merging with the Other in the way he wished.[46] However, when we consider Genet’s relationship to Jackson using Jackson’s analysis of the lumpen class, the connections between their respective material circumstances and structural positions are not so trivial as they initially seem.

“La prison est l’école de la révolution” / The Prison is the School of the Revolution

In “Foucault and the Black Panthers,” Brady Thomas Heiner discusses the hidden influence of the BPP on the work of the French philosopher-historian Michel Foucault. Heiner notes that it was Genet who introduced Foucault to the BPP, and it is also widely known that it was Genet who suggested that the Groupe d’Information sur les Prisons (GIP)—a French prison activist organization founded by Foucault, Jean-Marie Domenach and Pierre Vidal-Naquet—produce a pamphlet on the assassination of George Jackson. Given that Foucault is one of the most cited authors in the humanities, it is somewhat surprising that the history of the prison activist organization the GIP is not widely known in the US. Very few of the essays and documents produced by the GIP have been analyzed in anglophone contexts, and the connection between the GIP and Black radicalism has only been discussed in a handful of articles by Jason Demers, Michelle Koerner, and Brady Thomas Heiner. The GIP was founded in 1971 with the aim of making the prison more porous by creating communication networks that would circulate information into and outside of French prisons. Though the GIP was short-lived, they produced a number of documents, hosted events, publicly supported prison revolts, and published four pamphlets in a series titled Intolérable: an investigation of twenty prisons (conducted by the organization itself), an investigation of a model prison (Fleury-Mérogis, near Paris), a collection of essays and interviews following the assassination of George Jackson, and a pamphlet on suicides in French prisons, which include the GIP’s correspondence with a gay inmate who committed suicide while in prison. In addition to the four Intolérable pamphlets the GIP also published a number of essays in other journals and held press conferences to intervene in the mainstream media’s representations of prison struggles. Days after the Attica uprising the GIP published a text in the journal La Cause du peuple, which also featured a contribution by Genet. Several weeks later, on November 11, 1971, the GIP held a “prison meeting,” which drew over 6,000 people.[47] During the event the GIP screened two films on the prisons of Soledad and San Quentin, where Jackson was held.

In the essay on the Attica uprising that the GIP wrote for La Cause du people, they wrote that the prisoner struggle represents a general struggle against racism and fascism. The essay invokes an international prison movement that links the prison revolts of the US, France, Italy, and England. Borrowing the rhetorical flourishes of Black radicals, the GIP writes, “La vie et la mort de Jackson, le massacre d’Attica ont révélé que les prisons amérikkkaines sont aussi des foyers de formation de militants révolutionnaires” (The life and death of Jackson and the massacre of Attica have revealed that Amerikkkan prisons are also the hotbed of the formation of revolutionary militants).[48] The article also declared that the prison “est l’école de la révolution” (is the school of the revolution).[49] The text was also illustrated with images from the Attica revolt. By claiming that prisons are the school of the revolution, the GIP centers the prison as a site of intellectual production. Following Jackson, the GIP’s statements also support Jackson’s claim that the prisoner class is full of revolutionary potential.

“L’assassinat de George Jackson” / The Assassination of George Jackson

Intolérable #3, “L’assassinat de George Jackson” (The Assassination of George Jackson), was one of the first texts by the GIP to be translated into English, perhaps because the other three issues all pertain to French prisons and are less relevant to English-speaking audiences than a text on a US Black radical. Prior to the 2021 publication of Intolerable Writings: from Michel Foucault and the Prisons Information Group (1970–1980), sections of “L’assassinat de George Jackson” were translated into English and published in Warfare in the American Homeland: Policing and Prison in a Penal Democracy, edited by Joy James and published in 2007. According to English translator Sirène Harb, “It was at [Genet’s] suggestion that the GIP devoted a communiqué on media coverage of George Jackson’s death in San Quentin.”[50] Though the authors of the original French pamphlet were anonymous, James’ Warfare in the America Homeland anthology attributes authorship to Michel Foucault, Catherine von Bülow and Daniel Defert. Following James, Heiner also attributes authorship of the pamphlet to Foucault, von Bülow and Defert. However, in the English scholarship on the GIP, there has been no consensus on who authored the pamphlet. In an editorial note James writes, “Some also attribute authorship of this pamphlet to Gilles Deleuze, but research was unable to support this claim.”[51] Because there has been a great deal of confusion about who exactly were the authors of the GIP George Jackson pamphlet, articles that attempt to assess the influence that Black radicals such as Jackson have had on French intellectuals have remained largely speculative. For instance, Heiner’s “Foucault and the Black Panthers” is based partly on the assumption that Foucault was the primary author of the pamphlet. However, a closer look at the pamphlet itself, and the discrepancies between the English translation and the original French text give clues as to who the authors were, which would enable a more accurate assessment of how Black radicals influenced French intellectuals such as Genet, Deleuze and Foucault.

“L’assassinat de George Jackson” consists of five sections preceded by a short editorial note and a preface that was written by Genet but was signed with the initials “J.G.” (purportedly because Genet did not want to be associated with the French intelligentsia). The final three sections consist of three separate essays on various aspects of Jackson’s assassination and legacy. Section three, “L’assassinat camouflé” (translated in Warfare as “The Masked Assassination”) is a point-by-point analysis of the contradictions and discrepancies in the mainstream media’s reporting on the assassination of Jackson. The fourth section, “Après l’assassinat” (“After the Assassination”) discusses the suppression of the testimonies of inmates who witnessed the murder of Jackson. The fifth and final section, “La place de Jackson dans le mouvement des prisons” (“Jackson’s Place in the Prison Movement”) discusses Jackson’s analysis of prisoners as a revolutionary class and how Jackson’s death catalyzed a wave of “revolts that exploded in prisons.”[52]

Given the five-part structure of the pamphlet, and the fact that the GIP was a collective undertaking, it is likely that the pamphlet is polyvocal and that multiple authors were responsible for the text. There are a number of clues that would suggest that section three was written by Foucault, section four was written by Deleuze and the final section may have been written by Genet or another member of the GIP. An Italian version of the pamphlet, which was published in 1971 (around the same time as the original French version) attributes authorship to Foucault, Deleuze and Genet. The third section, “L’assassinat camouflé,” seems likely to have been written by Foucault because it deals primarily with the production of truth and knowledge as a form of power. Furthermore, one possible clue of the authorship of the fifth section is the reference it makes to a revolt among Palestinians at the Israeli prison of Ashkelon. Joy James notes that Palestinians at Ashkelon began to revolt eight days after the Attica uprising. Given that Genet was involved in the production of the pamphlet and went on to visit Palestinian refugee camps in Jordan months after traveling with the BPP, it is possible that Genet might have authored this section. Genet was involved with the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) and made four trip to the Middle East from 1970-1972, so the revolt at Ashkelon would have likely been on his mind.

Lastly, there is quite a bit of reason to believe that Deleuze authored the fourth section, “Après l’assassinat.” Though James’s editor’s note asserts that research was unable to support the claim that Deleuze participated in the writing of the pamphlet, there is much evidence to the contrary. First, the Italian version of the pamphlet, which appeared around the same time as the original French version, includes Deleuze as one of the authors. Second, the “Après l’assassinat” section includes a Jackson quote that Deleuze cited in almost all of the writings he produced during this period. As Koerner and Jeremy Matthew Glick have noted, Deleuze uses the following quote from Soledad Brother to elaborate his concept of “line of flight” (“une ligne de fuite”): “I may run, but all the time that I am, I’ll be looking for a stick! A defensible position!”[53] For Deleuze this quote is useful insofar as it demonstrates that escape or the flight of the fugitive—far from being a form of retreat—can simultaneously be a mode of revolt. Despite the appearance of this quote in a number of works by Deleuze, the connection between Jackson and Deleuze “has thus far only been noted in passing.”[54] Glick’s article “Aphoristic Lines of Flight,” which discusses Jackson’s thought alongside the Deleuze-influenced political theory of the French ultra-leftist group Tiqqun, analyzes the transpositions Deleuze made when quoting Jackson in French, sometimes substituting gun or weapon (“une arme”) for Jackson’s “stick.”

It is possible that anglophone scholars were late to make the connection between Jackson and Deleuze because of James’ dismissal of Deleuze’s involvement with the writing of the Jackson pamphlet, and Harb’s translation of the final three sections of the pamphlet. In the original French text, the fourth section concludes with the sentence “L’assassinat de Jackson est de ces choses, une ligne de fuite, comme dirait Jackson, ou les révolutionnaires s’engagent,” which Harb translates as “The assassination of Jackson is one of these phenomena, a defensible position, as Jackson would say, that revolutionaries can transform into a cause.”[55] However, the choice to translate “une ligne de fuite” (a line of flight) as “a defensible position” in the English version is significant in that it effectively erases Jackson’s connection to a concept that was elaborated specifically by Deleuze, which further reinforces the claim that Deleuze did not contribute to the writing of the Jackson pamphlet. Though it is impossible to determine why the translator (or editor) chose to replace “a line of flight” with “a defensible position” (it is possible that this phrase was chosen because it’s true to Jackson’s wording rather than Deleuze’s paraphrasing of Jackson’s words), the effect is that the main clue that links Deleuze to the authorship of this section of the pamphlet would not be known to English readers, which in turn may have contributed to the confusion surrounding the authorship of the pamphlet among anglophone scholars. The most recent translation of the text by Perry Zurn and Erik Beranek also opt for the phrase “a defensible position” because, as they note in a footnote, it was Jackson’s original wording.[56] Finally, another reason why one can reasonably say that Deleuze wrote this section is the widely-agreed upon claim that Deleuze was the author of the final GIP Intolérable pamphlet, “Suicides de Prison” (which has not been translated into English). Like the fourth section of the Jackson pamphlet, the essay that discusses the letters of H.M.—a homosexual prisoner who committed suicide—also makes reference to the concept of a line of flight while referring to the same Jackson quote mentioned in the Jackson GIP pamphlet.

While a full treatment of the influence of Jackson on the thought of Foucault and Deleuze is beyond the scope of this article, I want to highlight how the concept of the line of flight was taken up by Deleuze. In Dark Deleuze, interdisciplinary media scholar Andrew Culp rejects the “canon of joy” interpretation of Deleuze that casts him as a philosopher of positivity and connectivism.[57] Culp uses Deleuze’s reading of Jackson to emphasize the “destructive force of negativity” embodied in Jackson’s proclamation that “during my escape, I’m looking for a weapon.”[58] During a 1973 address, when Deleuze was asked a question about memory and forgetting in Freudo-Marxism, he began his response by making a Nietzschean distinction between “forgetting as a force of inertia and forgetting as an active force.” The latter, for Deleuze, is a revolutionary form of fugitivity insofar as the revolutionary can wipe clean the slate of the status quo, despite the protestation that “It has existed, therefore it will always exist.”[59] Deleuze goes on to make a distinction between “passive escape” and “active escape,” the active kind being embodied by Jackson’s attempted prison escape and line of flight out of the social formation.

Conclusion: The Circulation of the Global Prison Abolitionist Imagination

What is prison? It is immobility. “Free man, you will always cherish the sea!” (Baudelaire). It is becoming more and more obvious that mobility is one of the signs of our times. To restrict a man for eleven years to surveying the same four or five square meters—which in the end become several thousand meters within the same four walls opened up by the imagination—would justify a young man if he wanted to go … where, for example? To China perhaps, and perhaps on foot. Jackson was this man and this imagination, and the space he traversed was quite real, a space from which he brought back observations and conclusions that strike a death blow to white America (by “America” I mean Europe too, and the world that strips all the rest, reduces it to the status of a disrespected labor force—yesterday’s colonies, today’s neocolonies). Jackson said this. He said it several thousand times and throughout the entire world. It still remained for him to say truths unbearable for our consciences. The better to silence him, the California police …. But what am I saying? Jackson’s book goes far beyond the reach of this police since it is read, praised, commented, and continued by nine-year-old blacks.

—Jean Genet, “After the Assassination”[60]

When Genet writes about George Jackson’s words echoing throughout the entire world, he is hardly exaggerating. No matter how many attempts are made to police and silence Jackson’s message, his legacy endures and continues to inspire revolts, such as the hunger strikes that took place across California prisons in 2013. The force of Jackson’s visionary political imagination is so powerful that it carries his message around the world. This essay deals with only a tiny corner of the whole of Jackson’s global impact: his influence on the French intelligentsia.

The engagement of French intellectuals such as Genet, Foucault, and Deleuze with the writings and struggle of Jackson shows how the prison abolitionist imagination circulates globally, through transatlantic material and discursive networks. Jackson may have spent all of his adult life in prison, but his words circulated, and continue to circulate, far beyond the walls of his prison cell. As he writes in Blood in My Eye, “I can only be executed once.”[61] But his execution can never be total, for it cannot stop the circulation of the prison abolitionist imagination.

- [1] Jean Genet, “Trésors d’archives-Lettre de Derrida à Genet,” Magazine Littéraire 464 (2007), 96.

- [2] Ibid.

- [3] Jean Genet, The Declared Enemy: Texts and Interviews (Stanford: Stanford University, 2004), 303. Robert Sandarg, “Jean Genet and the Black Panther Party,” Journal of Black Studies, vol.16, no. 3 (1986), 270.

- [4] Genet, The Declared Enemy, 42.

- [5] Phillipe Artières, Laurent Quéro, and Michelle Zancarini-Fournel, Le Groupe D’information Sur Les Prisons: Archives D’une Lutte, 1970-1972 (Paris: Institut Mémoires De L’édition Contemporaine, 2003), 93.

- [6] Arie Nicolaas Jan Den Hollander, Contagious Conflict: The Impact of American Dissent on European Life (Leiden: Brill, 1973), 55.

- [7] Associated Press, “Other Prison Uprisings Linked to Riots At Attica,” Sarasota Herald Tribune, September 23, 1971.

- [8] Beth Mauldin, “Searching for the Revolution in America: French Intellectuals, Black Panthers and the Spirit of May ’68” Critique, vol. 36, no. 2 (2008), 233.

- [9] George Jackson, Blood in My Eye (New York: Random House, 1972), 174.

- [10] Mauldin, “Searching for the Revolution in America,” 241.

- [11] Ibid, 234.

- [12] Ibid 239; Henry Raymont, “Gary Comments on Student Riots,” The New York Times, August 21, 1968.

- [13] Agnès Varda and T. Jefferson Kline, eds., Agnès Varda: Interviews (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2014), 91.

- [14] Mauldin, “Searching for the Revolution in America,” 241.

- [15] Ibid.

- [16] Genet, The Declared Enemy,43

- [17] Ibid, 60.

- [18] Dan Berger, Captive Nation: Black Prison Organizing in the Civil Rights Era (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2014), 110.

- [19] Ibid, 110.

- [20] See the appendix, “Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses” in Louis Althusser, On the Reproduction of Capitalism: Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses, trans. G.M. Goshgarian (London: Verso, 2014).

- [21] George Jackson, Soledad Brother: The Prison Letters of George Jackson (Chicago: Lawrence Hill, 1994), 337.

- [22] Ibid, 337-338.

- [23] Ibid, 335.

- [24] Genet, The Declared Enemy, 43.

- [25] Jackson, Soledad Brother, 336-337.

- [26] In a letter to his father Robert, Jackson wrote: “None of the Western European cultures know anything about philosophy (love of knowledge). They know nothing of the proper way that men should carry on their relations with other men.” Jackson, Soledad Brother, 114.

- [27] Genet, The Declared Enemy, 42.

- [28] Mikkel Bolt Rasmussen, “Yes of Course, but … Derrida to Genet on Commitment in Favour of Jackson” New Formations 75 (2012), 147.

- [29] Ibid, 149.

- [30] Genet, The Declared Enemy, 44.

- [31] Ibid.

- [32] Ibid.

- [33] Ibid, 48.

- [34] Ibid.

- [35] Jackson, Soledad Brother, 332.

- [36] Jackson, Blood in My Eye, 175.

- [37] Ibid, 181.

- [38] Genet, The Declared Enemy, 3.

- [39] Jackson, Blood in My Eye, 184.

- [40] Rassmussen, “Yes of Course, but…”, 146.

- [41] Genet, The Declared Enemy, 3.

- [42] Jackson, Soledad Brother, 338.

- [43] Jackson, Blood in My Eye, 184.

- [44] Nathalie Fredette, “Genet politique, l’ultime engagement,” Études françaises, vol. 29, no. 2 (1993), 91.

- [45] Ibid.

- [46] Ibid, 90-91.

- [47] Artières et al, Archives D’une Lutte, 214.

- [48] Ibid,124.

- [49] Ibid.

- [50] James Joy, ed., Warfare in the American Homeland: Policing and Prison in a Penal Democracy, (Durham: Duke University, 2007), 138.

- [51] Ibid, 157.

- [52] Ibid, 156.

- [53] Jackson, Soledad Brother, 328.

- [54] Michelle Koerner, “Line of Escape: Gilles Deleuze’s Encounter with George Jackson” Genre, vol. 44, no. 2 (2011), 158.

- [55] Philippe Artières and Groupe D’information Sur Les Prisons, Intolérable (Paris: Gallimard, 2013), 209; Joy, Warfare in the American Homeland, 154.

- [56] Kevin Thompson and Perry Zurn, eds., Intolerable: Writings from Michel Foucault and the Prisons Information Group (1970–1980) (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2021), 159.

- [57] Andrew Culp, Dark Deleuze (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2016).

- [58] Ibid.

- [59] Gilles Deleuze, Desert Islands and Other Texts, 1953-1974, trans. Michael Taormina (Los Angeles: Semiotext(e), 2004), 277.

- [60] Genet, The Declared Enemy, 87

- [61] Jackson, Blood in My Eye, 181.