Greenberg avec Mao: Supports/Surfaces and the Specific Contradiction of Painting

What is not quite literal testifies to the tense non-identity of essence and appearance.

Theodor Adorno[1]

We have grown used to a foregone conclusion about the impact of the French uprisings of May 1968 on the field of culture: namely, revolution’s collapse and art’s return to arthood. In the moment there was no such script. The essay that follows is about a passage through the vicinity, if not of revolution per se, then of its specter. The trajectories at issue had points of origin well prior to 1968 but found themselves rerouted (détournés, in the literal sense) by that encounter; the apparent imminence of revolution at a particular time in history was a factor with which the artists of the group Supports/Surfaces—my case study here; the same was true of many others—had to negotiate in order to continue producing work at all in the aftermath of les événements. This pressure exerted certain formal effects on their art, as did capitalism’s resilience. Jockeying in the market of radical chic and jockeying in the art market proper were both in play and not always distinguishable. Yet: the French state had come close to falling, or so it seemed. Revolution was a body in the room. Artists could feel its heat, nearer or farther off. And the ideologies of critique, of artistic and political vanguardism, or of “French theory,” as it eventually came to be known, were means of keeping revolution at bay as much as of stoking its embers. The later descent of so many of the French intellectual scene’s luminaries into reaction or just tedium has perhaps made it difficult, now, to conjure the intensities of the moment, or anyway to take them seriously. It bears emphasizing that this potential lack of seriousness—this potential absence of a link between art and revolution—was as it were built into the conjuncture and felt to be so at the time. Supports/Surfaces rarely enjoyed a credulous public.

In any case, the fact to be explained is this: after 1968, a certain French painterly “formalism” (though its protagonists were careful not to describe it as such) was embedded within, and took its contours from, the pressure-chamber of leftist politics—particularly of Maoism, the nation’s dominant gauchiste tendency from approximately 1970 to 1975. At more or less the same moment, this set of practices drew from Clement Greenberg’s writings on modernist art, and more broadly from the corpus of American postwar abstraction that was Greenberg’s dominion, for an account of painting’s specificity as a (semi-)autonomous practice. The simultaneous collapse of modernist criticism and of Maoist politics by the mid- to late 1970s accounts for the persistent occlusion of Supports/Surfaces as a factory of theory rather than as a factory of (saleable) objects. For the most part, commentators have found it adequate to note that Supports/Surfaces produced a great deal of writing, without bothering to say what exactly all of that writing was about.[2]

This scission of theory from practice is contrary to the stated aims of Supports/ Surfaces, even as it follows logically enough from the contradictions of their project—contradictions that led to the group’s implosion nearly as soon as it got off the ground. The aim of Supports/Surfaces at the turn of the 1970s was to make of their work a dialectical and material practice, a practice that would effectively theorize itself in form. They explained as much in a torrent of words. Texts by members of the group propose that painting is or at least can be two things at once: first, a scientific “theoretical practice,” in the terms of the Marxist philosopher Louis Althusser,[3] and second, a form of production, analogous to the “textual production” that Philippe Sollers, Julia Kristeva, and other writers associated with the journal Tel Quel (for whom Supports/Surfaces functioned as something like an official painterly avant-garde) were in the process of conceptualizing in the same moment. Their reflections were distributed across a number of catalog essays, books, and periodicals, among them Supports/Surfaces’ own house journal, Peinture, cahiers théoriques, which was founded in 1971.

The bulk of my analysis will be devoted to the writings of Marc Devade: painter, poet, member of the editorial board of Tel Quel from 1971 until near to his death. He was both a founding member of Supports/Surfaces and arguably the group’s most ambitious theorist of painting, the last honor under stiff competition from Daniel Dezeuze and Louis Cane, however. Nota bene: these essays represent a particular version of Supports/Surfaces, not a unanimous party line. The identification of Devade, Dezeuze, and Cane (or Devade alone) with the group’s theoretical position, full stop—plausible thanks to their dominance in Peinture, cahiers théoriques—suggests a degree of unanimity that never was. Such unanimity as did exist was disputed from the start; the group’s Nice-centered faction (Noël Dolla, Patrick Saytour, André Valensi, and Claude Viallat) defected as early as 1971. By the following year Supports/Surfaces had for all intents and purposes ceased to exist, though Peinture, cahiers théoriques remained in publication through 1985, even briefly surviving Devade’s premature death in 1983. The difficulty of generalizing about “Supports/Surfaces theory,” then, is that there really never was any such thing. In practice, too—that is, in the collective exhibitions of 1970 and 1971—the art of Supports/Surfaces never congealed into a uniform style, even within the Devade/Dezeuze/Cane triumvirate. Devade pursued a systematized variant of American Color Field painting (Mark Rothko, Barnett Newman, and Morris Louis are the closest precedents). Inspired by Chinese painting, his work after 1971 was executed mostly in ink, rather than paint, on canvas. Although Devade was the group’s most radical theorist, he was also arguably its most conservative practitioner, insofar as he consistently accepted the integrity of the picture plane as a basic parameter. Dezeuze, by contrast, was concerned above all with painting’s physical support, that is to say, with the grid of the stretcher. Cane, in turn, investigated the physical painting surface by cutting out and folding rectangular sections of either monochrome or multicolor canvases, from 1972 generally onto the floor and thus into the viewer’s space. (The first of his cutouts would appear to date from 1970.) Although perhaps equivalently “deconstructive” in their various modes, it is as if these three artists had assigned themselves a division of painterly labor: where Devade tested the nuances of color and the minimal conditions of illusionistic space—retaining a conception of the picture as an image, rather than object—Dezeuze stripped the canvas away almost entirely in order to expose its material infrastructure. Cane, finally, reduced Devade’s numinous membranes of color to a flatter simplicity, the better to annul illusionism in favor of a literal surface that could then be unfolded into real space: though here, too, Cane’s use of gradients implies a minimum of illusionistic recession and thus anti-literalism. Others among the group’s initial members, such as Viallat and Dolla, in turn explored the desubjectifying potential of repetitive marks and patterns, both readymade and hand-painted. These modalities may be complimentary, but they are far from identical in either purpose or effect. The group’s name is hence a copula that expresses while also papering over the heterogeneity of its participants’ artistic production.

The specificities of these practices deserve separate analysis. The present article ought to be read as a gloss on Devade’s writings circa 1969-71, to which can be appended the writings of Cane and Dezeuze from the same period insofar as the three presented a common front during their collaboration on the handful of Supports/Surfaces group exhibitions as well as in the production of Peinture, cahiers théoriques. I cannot tender an account of “Supports/Surfaces-type practice” in general, nor can I do any justice to artists such as Saytour and Viallat, who in many ways were pursuing different aims.[4] The question to be asked of Devade’s texts is not whether they got painting “right,” or even whether they got Supports/Surfaces right, but rather: How was it possible (plausible) to think of painting in these terms at all? And why has it not been possible since? At stake is a defense not of Supports/Surfaces’ pungent blend of Maoism, Althusserian Marxism, Derridean deconstruction, Lacanian psychoanalysis, and—last but not least—formalist art theory à la Greenberg, as such, but rather of their commitment to formalization as a productive “theoretical practice” (to invoke Althusser’s term again). The word “productive” should be taken literally here. Supports/Surfaces theory was not (only) a description or justification of what these artists were already doing, at some other scene—the scene of painting—but was rather a generative problematic in its own right.[5] Theoretical production ran parallel to and was complexly mediated with their painterly output, but it possessed all the same its own impetus and logic.

Such a pursuit was meant to be collective, and it had as its named if not actual horizon nothing less than communist revolution. In point of fact, Tel Quel had followed the French Communist Party’s official line on May ’68: that it had been a petty-bourgeois revolt, not a genuine revolution; their non-participation in the barricades and occupations thus had a readymade rationale.[6] These events were all the same to trigger a profound reorientation for both Tel Quel and Supports/Surfaces in the years to come. At least part of their virulent Maoism circa 1971 has to be read, then, as compensation for missing out on the festivities. And it is this missed encounter, one might further argue, that accounts for the peculiar articulation of theory and practice in Peinture, cahiers théoriques and other manifestations of Supports/Surfaces activity, of which Devade’s writings are, I would submit, both an impressive and problematic result (problematic because the relation of his texts to the group’s collective production—more bluntly, the fact that what Devade has to say does not seem to apply very well to much of the work made by other Supports/Surfaces members—was to remain unresolved, in part simply because the group did not survive long enough for such inconsistencies to be ironed out). The group’s journal was a stage on which both painting’s (semi-)autonomy and its fitting to the needs of Maoist politics could be worked through. Both aspects of the program were equally explicit. It was also in this conscious and jointly pursued aesthetico-political alchemy that the members of Supports/Surfaces saw an escape from the atomism of the capitalist art industry. Devade’s justification for the founding of Peinture, cahiers théoriques (as published in the fifth issue of VH 101, another French art journal of the period) is as follows:

[…] in the face of the inflation of neurotic individual practices encouraged by the painting market and its press, the foundation of this group was a positive act, an active defense of a certain type of painting as a theoretical practice, as a specific materialist practice, despite its empirical effects. It thus constitutes the essential base of support for a certain number of painters who aim not only at the transformation of their practice, but rather, through this, at the transformation of the economic and social field that conditions them; a transformation in which no practice of an individual type can claim to operate effectively, even if it dresses itself up with theoretical borrowings.[7]

Hence collectivism, of however short duration. Now that we know something of Devade’s context and motives, we can proceed to gauge his theoretical accomplishments.

Painting Degree Zero

I have said that the artists I am considering aimed to make of their work a dialectical and materialist practice. We can be more precise. The program of Supports/Surfaces was a destruction of the ontotheology of painting, which is to say, of any recourse to immediacy, to expression, or to the identity of signifier and signified in the creative act. It was a proposition that painting could be disenchanted, but still made. Painting could indeed be a “theoretical practice,” a “specific materialist practice,” productive of knowledge rather than ideology. As Althusser had discerned in Marx’s mature writings an “epistemological rupture” with the “religious complicity between Logos and Being,”[8] and as Jacques Lacan had explicated the split in the subject, Supports/Surfaces announced a break with every notion of painting as a practice free of constitutive fissures. It was, significantly, painterly practice that gave the lie to painting’s native ideology: first, in the canonical modernists of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries (especially Cézanne and Matisse) and then—somewhat in the manner of Althusser’s return to Marx, or Lacan’s to Freud—in the work of Supports/Surfaces itself, whose efforts, by the group’s own account, returned to and in a sense completed the revolution begun with the emergence of modernism a century before.[9] That revolution was to be part of a general demystification of the sign, allied with Kristeva’s “revolution in poetic language,” with Jacques Derrida’s structure of différance, and with Jean-Joseph Goux’s semiotic analysis of money, to name a few of Tel Quel’s touchstones. As they understood it, the isolation and analysis of painting’s basic parameters was an inquiry into the workings of signification at its most irreducibly material level. Catherine Millet, one of the group’s more important critics, would some years later use a phrase of Roland Barthes’ to summarize the contribution of Supports/Surface: “It is painting degree zero: the highlighting of its constituents becomes the very purpose of the work, and they are exploited in such a way as to reveal their specific characteristics and effects.”[10]

This, in short, is the argument of the texts published in the first few issues of the group’s journal. But their critique of painting’s self-presence did not spring into existence full-grown with the establishment of Supports/Surfaces in 1970. Devade, in particular, had been developing a materialist critique of painting for some time already, in close parallel with Lacanian psychoanalysis, deconstruction, and Althusserian Marxism (most of the younger representatives of which, at the turn of the decade, were sliding decisively towards the Maoist camp). In common with Sollers and Tel Quel in general, Devade and his comrades furthermore sutured these discourses to a rather naïve Sinophilia. They were particularly enamored of the idea that ancient Chinese philosophy and artistic theory already constituted a form of dialectical materialism thanks to Chinese culture’s apparently inborn resistance to logocentrism.[11] A final strand of influence was the example of artistic modernism itself, not excluding its most recent American variants: that is, painting in the wake of Abstract Expressionism, and the writings of Clement Greenberg.

Take, for example, Devade’s essay “Chromatic Painting,” which appeared in the 1970 issue of Tel Quel in which Derrida also published the first part of his “Double Session” on Mallarmé. The essay is a convenient case study for two reasons: first, because of its early date (and prominent site of publication), and second, because it has been available in English since the 1990s.[12] Here, Devade describes the “theoretical material practice of the surface”—that is, materialist painting—as “the practice of spacing that constitutes the articulation of the movement of production (time) and pictorial space.” This “spacing” happens on and as the surface. It happens not between discrete surfaces, or on top of them—that is, in physical relief—but rather as the thin layer of a painting’s colored flatness. A materialist practice of painting preserves rather than conceals this spacing. To do so implies a break with any form of traditional Western illusionism, or indeed with any form of seamless pictorial totality, modernist versions included. It implies a break with any mode of picturing that fetishistically conceals its production, as does the commodity-form in Marx’s account: “The obliteration of the spacing of the surface (through a perspectival reduction) is, then, the obliteration of production, and the desire for a final return to a substantial unity that is mono-chromatic or visual.”[13] Both perspectival illusion and the monochrome are equally totalizing, equally reified; they are both systems that leave no remainder. In contrast: “Materialist pictorial production takes place only as the detour of limits, where the desire for unity is constantly subverted by the real practice of painting which demonstrates explicitly the non-existence of that unity, the illusion in its infinite differences (differances: J. Derrida).”[14]

Like Jean-Joseph Goux in nearly the same moment, Devade interprets Derrida’s assault on presence as the impetus for a critique of capitalist fetishism, or in other words, the concealment of relations of production behind the seamlessness of the commodity-form.[15] Materialist painting is then nothing less than the expropriation of the expropriators: “The production of painting, until this point monopolized by the reproduction of an exterior subject, seizes those means of production expropriated in the service of representation and practises itself dialectically in an objective space which it makes readable as history.”[16] To rephrase Devade’s point in a more recent language—that of the art historian Sebastian Egenhofer—materialist painting thus lays bare the “vertical dimension” of the production of semblance, the dimension of the trace and the archive, which is concealed by a constitutive forgetting in the present of aesthetic experience.[17]

This occurs fundamentally in the tension between surface and support. For Devade, although the unpainted plane is an “empty volume,” there is really never such a thing as an empty canvas. Painting has rather “always-already begun.” The bare canvas is already a visual fact, a “graphic surface,” even if its color is white or the neutral beige of untreated fabric. The latter surfaces function as, in Devade’s terminology, a “non-chromatic limit to its [the picture’s] chromatic infinity.” The addition of pigment is thus already a doubling of the (colored) surface, or, as he puts it, “the production of at least one chromatic color on a surface of non-chromatic color.”[18] The painted surface is thus a “sur-face” in the literal sense, something “above” (sur) the “face” of the canvas. This doubled sur-face is what Devade calls the chromatic. The chromatic has less to do with color per se than with a certain minimum of “illusion in its infinite differences.” And because—at least in materialist painting, painting that does not dissemble its genesis—the “graphic” and the “chromatic” aspects of, respectively, the painting’s (material) support and its (doubled) surface always remain immanently entangled, it is this infinite play that is painting’s basic generative operation. Materialist painting does not abolish illusion so much as spin it out, ceaselessly, without any underpinning other than this oscillation between surface and support.[19]

So: the “spacing” between the chromatic mark and its non-chromatic ground is irreducible and has always-already-begun, even as the two are inseparable, precisely because each is what prevents the other from congealing into a totality. In a somewhat unexpected way, it is hence the chromatic mark that “defers”—that forestalls the self-presence of—the “empty volume” of the blank canvas or “graphic” surface.[20] As Devade puts it: “The theoretical practice of painting is the articulation of the graphic surface and the pictorial surface that defers it; this articulation produces not a contradiction but an equivalence or identity of the chromatic and the non-chromatic”; “This deferral of the empty volume (irreducible to the following terms: form-content, outside-inside, same-other, since one is the other, one is already the other, one only is through the other) is the material and real production of the surface, of a pictorial surface.”[21] Playing again on Derrida, Devade further writes: “Painting produced by this means is archi-painting, so named because it announces the becoming of painting beyond the cut effected by its present production; painting as diagram of colours.”[22] Chromaticism is an effect of painting’s system but also transgresses it.

Nothing is left here for a discourse of expression. At stake, rather, is a notion of painting producing both itself and its own transgression, along with an attached subject—the painter—but not as something so straightforward as the realization of latter’s intentionality.[23] It is instead closer to the reverse: the painting-operation produces its subject, and not the other way around. (Within another two years, Devade and Cane would more insistently thematize the artist’s subjectivity in terms of chromatic “pulsion,” which they link to the pre-Oedipal drives at the center of Julia Kristeva’s contemporaneous theorization of the “subject in process.”)[24] “The plane is not the mise-en-scène of an expression or of a vision projected onto this plane (which would preserve the ideological division of the spectator and actor, spectator and painting, ‘artist’ and painting), but the mise-en-scène of painting through the effects of its real production; as an object produced by its own structure: by its format.”[25] Finally, since the viewer’s perception of the work is likewise an effect of structure, or of “format,” there emerges a curious elision of the painter (the subject of practice) with the viewer (the subject of consumption): “The author-actor-spectator of this mise-en-scène is none other than its own structure elaborating itself, playing itself in a mechanical program of which we are the contingent readers.”[26] Both author-painter and reader-viewer have well and truly died, then.

The reference to Derrida is clear throughout the passages I have been discussing, and of course I have just alluded to Roland Barthes, another of Tel Quel’s fellow travelers. But this way of putting things is moreover a precise translation of Althusser’s concept of “structural causality,” to which Devade also explicitly refers. A structure, for Althusser and, following him, Devade, is entirely immanent in its effects. There is not a structure outside of painting that generates its phenomenal appearance, as would be the case in certain mystical theories of emanation, or in a certain idealist version of structuralism. Rather the painting is its structure, in its apparently immediate materiality. This is a relational approach to the interaction between part and whole—between the individual painterly mark or motif and the holding together of those marks as a system or provisional totality. Devade usefully cites Mondrian on this point. In Mondrian’s words,

[…] all things are part of a whole, each part receives its visual value from the other parts. Everything is constituted through relation and reciprocity. A colour exists only through another colour, a dimension is defined by another dimension, there is no position except in opposition to another position. This is why I say that the principal thing is relation.[27]

Relation, by its nature, never resolves into finality. Painterly différance is rather the endless playing out of the structure that painting is, much as “text” or “textuality” is the effect of a similar operation in, say, Nombres, the experimental “novel” by Philippe Sollers that serves as Derrida’s nominal object of analysis in “Dissemination,” his own no less writerly “essay” of early 1969.[28] But this endlessness does not imply that nothing true can be said of painting, in a pat rehearsal of the visual’s supposed inexhaustibility. On the contrary. An understanding of structural causality is rather the condition of scientific as opposed to ideological knowledge of art. And Devade aimed to be scientific.

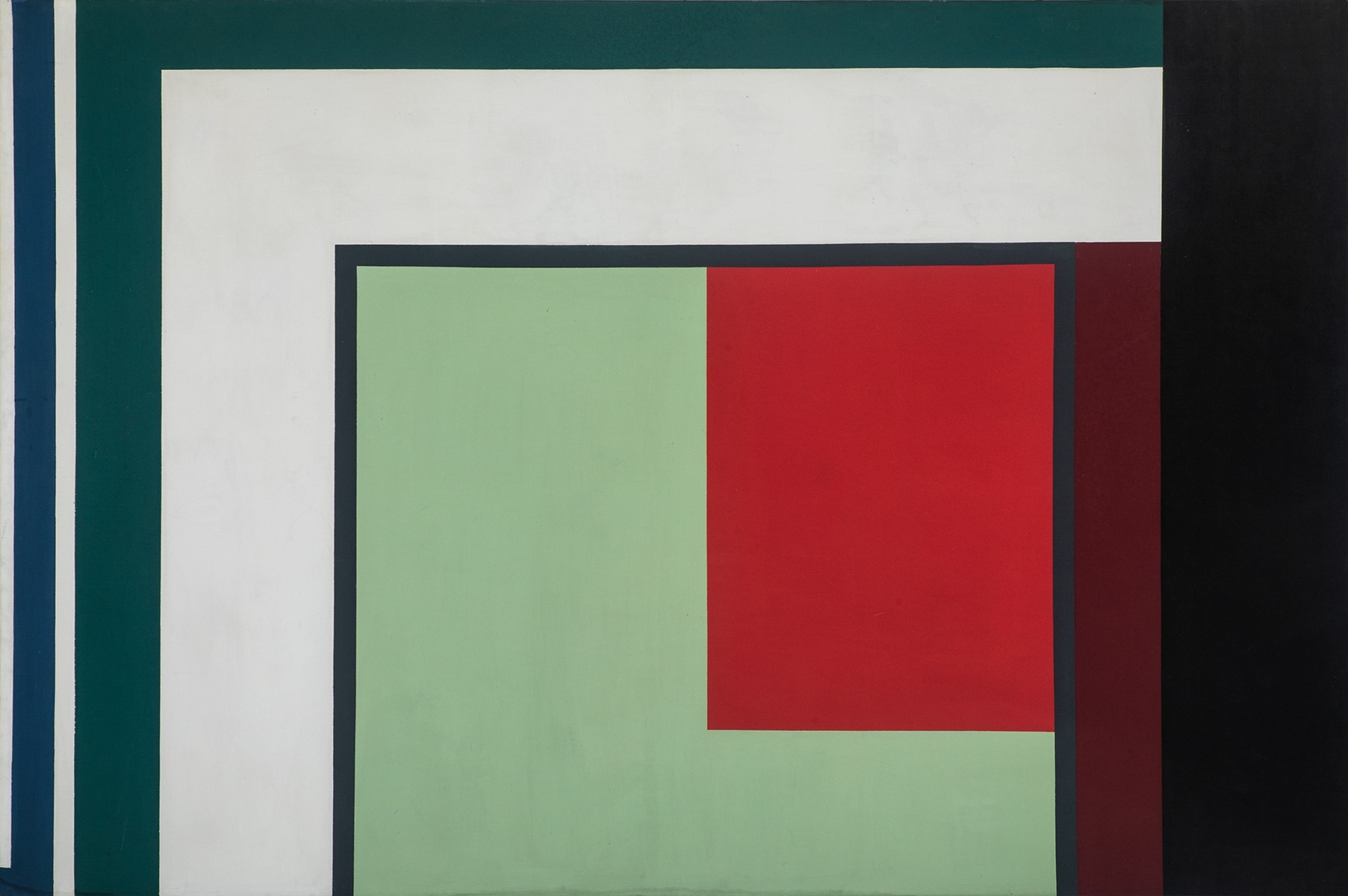

At this point it may be useful to look at a painting that Devade actually made, although my aim is primarily to read theory and not pictures. It is tempting to approach these artworks as illustrations of their author’s writing, or vice versa. In a sense there is no reason not to do so. His paintings transparently attempt to realize the principles of his theory, although we cannot presume that one went before the other. (Devade was in fact a writer before turning to visual art in the late ’60s, however.) His gambit is that the very distinction between theory and practice can and should be undone, if painting is, after all, a “theoretical practice” that explicates itself even as (written) theory continues and completes this self-explication. In poststructuralism, theoretical writing to some degree assimilates itself to the literary “text” it deconstructs, as “Dissemination” assimilates itself to Nombres. A similar relation ought to be at work in the loop between Devade’s pictures and his writing, with the added complication of a shift in medium.

Take a fairly typical work, albeit one that dates from somewhat later than the period of “Chromatic Painting”: Untitled, 1972. (Fig. 1) The medium is colored ink on canvas. The picture is large—over six feet tall. A remainder of bare fabric is visible at the bottom edge. There are a few more white streaks at the top. Apart from this, overlapping washes of ocher and purple cover the entire field. These are secondary rather than primary colors; unlike Mondrian, Devade saw no need to limit his palette to irreducible tones. Edges are irregular, generated by partly unforeseeable spillage. This is in contrast to Devade’s immediately preceding body of hard-edged work. The varied intensity and opacity of the planes is self-evidently the result of liquid ink being poured onto the fabric in one wash after another. Where two washes of purple and one of ocher overlap at lower left, some time has clearly been allowed for each to dry, since their edges are sharp. Elsewhere the ink pools and bleeds. The center of the picture—a rectangle that indexes the shape of its support—is a reserved lighter tone through which much of the raw canvas is perceptible, whereas the overlap between colors about two thirds of the way down, for example, produces what is almost an opaque line. The effects are simple and palpably result from a series of basic operations. At the same time, the “window” reserved at center and the viewer’s sense of overlapping transparencies lend the work proto-perspectival depth, a sense that the surface is being seen through. This format is very close to some of Louis Cane’s contemporaneous fold-outs. But with Devade, spatiality plays out entirely in illusion. The picture is in no way literalist, even as it flaunts its material production. The ink itself has almost no physical presence. It sinks into the texture of the canvas, which thus remains an insistent surface fact.

It may be surprising to find such evidently decorous late modernism stitched to such a portentous theoretical construct. The work is however nothing if not perspicuous about its dialectic of surface and support, and thus is faithful to its author’s theory. The bare canvas impinges on the chromatic surface as a visual fact and vice versa. They “defer” each other, in Devade’s words. Spatial illusion survives on its minimal conditions. The picture represents nothing even as it plays out the mechanics of representation. This is a work that aims to display its making as plainly as can be, even as it conjures a universe of non-identity: of illusion. In doing so it allows us to understand representation as a material effect, and, by the same measure, the material mark as the stuff of signification. The painting is an epistemological machine. Or a scientific demonstration.

So, what kind of knowledge does Untitled give us? To reach an answer, we have to consider what the word “science” would have meant to Devade circa 1970. The major figure here is, once again, Louis Althusser—or rather, a particular version of him. The Althusser of Supports/Surfaces is essentially the Althusser of 1965. The key texts are For Marx and Reading Capital, both published in that year. In fact, Devade and his comrades mostly do without citations altogether, taking key terms (preeminently the distinction between the “real object” and the “object of knowledge”) as simply understood. There is little indication that Supports/Surfaces deeply engaged with Althusser’s 1967 Philosophy and the Spontaneous Philosophy of the Scientists and other later texts, or even, more surprisingly, with his “Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses” of 1970. What follows, then, is an outline of Althusser’s epistemology circa 1965, filtered through Supports/Surfaces circa 1970.

For Althusser, no science is born ex nihilo. Science has no material other than the ideological material of a given practice or discipline. An empiricist approach to knowledge, such as Althusser criticizes in the first part of Reading Capital, distinguishes truth and falsehood by taking the given and then filtering the true from the false. To an empiricist, the true already exists within immediate experience and only needs extracting, like a nugget from a streambed. In Althusser’s view this gets things profoundly wrong. The true is not there for the taking, “out there” in the world. Knowledge must rather be produced. And it is “theoretical practice” that does the producing. Theory sets to work on the raw material of ideology and generates knowledge out of it, not by filtering the true part of reality from the false, but by inaugurating a decisive break, a “radical discontinuity,” between two objects of analysis: the “real object” and the “object of knowledge.”[29] His example is Marx. Marx’s Capital produces knowledge of an object called the “capitalist mode of production.” The book is not a description of any specific, empirical capitalist economy. Strictly speaking, “the capitalist mode of production” nowhere exists in the pure state that Marx describes. But Capital explicates the structure of this mode of production in a way that allows us to say things that we never otherwise could have said about the real world.

It is hence not that the “object of knowledge” is simply made up or has nothing to do with things as they are. Althusser wants to claim that an account of such a theoretical object produces valid knowledge about the real object to which it refers, without the theoretical object only being a model or representation of the real: the latter attitude reinstates an empiricist “mirroring” relation between knowledge and reality. Indeed, the entire epistemological project of Reading Capital is to show how such non-representational knowledge is possible. In particular, it is to show that Marx achieved his knowledge of capitalism through a break with Hegelian metaphysics and classical political economy.

Nonetheless, this doctrine of rupture easily lends itself to disconcerting extrapolations. A break with reality is, after all, something that most of us would presumably like to avoid. Moreover, as a science coheres, as it becomes formalized, and thus closes back over itself—as it constitutes a totality—it is hard to avoid the inference that a new ideology might very easily arise. Theoretical formalization comprehends what exists. And formalization is inherently totalizing. But the real is incomplete: Lacan had taught Althusser as much. Science aims at closure, which however it cannot achieve without the extinction of its object (the expulsion of ontological lack). “The real can only be inscribed on the basis of an impasse of formalization,” as Lacan accordingly says.[30] Jacques-Alain Miller, who studied with both Lacan and Althusser, put matters even more drastically in an essay he published in the journal Cahiers pour l’analyse in 1968: the epistemological break that establishes science as a discourse is its expulsion of lack, its self-closure or elimination of every unformalizable gap.[31] But, as Peter Hallward has noted in his paraphrase of Miller, “since ‘the lack of a lack is also a lack’, science can only relate to what it excludes—i.e. the domain of imaginary/ideological experience structured around lack—in terms of ‘foreclosure’ or exclusion as such.”[32] Althusser’s production of the theoretical object here radicalizes into an unmediated break between science and experience. Miller does not shrink from going so far to say that “every science is structured like a psychosis: the foreclosed returns under the form of the impossible.”[33] The epistemological break is a psychotic break. And the real takes its revenge.

This claim might very easily lend itself to the crassest idealism, namely, a suspicion that the world is only in our heads. The only thing that prevents it is the insistence of the untotalizable real. But from the perspective of theoretical practice, the “real” is precisely the material discourse upon which it works, the ideological and thus incomplete substance of the disciplines as they exist in history, and which must exactly be foreclosed in order for a science to achieve consistency.[34] A theoretical practice is therefore specific insofar as it takes up, transforms, or indeed generates a problematic from the real material of a discipline that constitutes it as a “specific contradiction” (to use a Maoist turn of phrase much in favor at the time). Painting is one such specific contradiction: Supports/Surfaces said so, verbatim.[35] And painting is a materialist theoretical practice insofar as the problematic of its discipline is grounded not in free-floating ideas but in actual relations. These are relations of production, of people to each other and to things, of subjects to objects. All of these relations are ideological, in their usual humming-along, and all of them are material; for Althusser, ideology is embedded in institutions and practices. Somewhat against expectations, then, it is nothing other than the contradiction-ridden materiality of ideology that prevents science from drifting away into the psychotic ether. Any claim to a decisive “break” or rupture absent this link to the material can only generate yet another ideology: that of falsely immediate, self-grounding knowledge.

Greenberg, Deconstructionist

Here we may finally return to the stakes of Althusserianism for Supports/Surfaces. For what is the tradition of painting but an ideology, an ideology of many and various things? (Ranging from the mystery of Christian incarnation to the scientistic dreams of Impressionism to the reiteration of the commodity-form in Pop Art.) And what is “materialist pictorial production” if not the working on, the working through, of this ideological stuff, with the aim of producing an “epistemological rupture” with, and within, painting as it had hitherto been made?[36] But not, importantly, of producing the abolition of painting, or the end of art as such. This would simply reproduce the empiricist or idealist illusion of an absolute beginning: truth ex nihilo, immediate access to non-ideological knowledge, the dualism of matter and spirit—in short, the “religious complicity between Logos and Being.” Abolition would, in its radical variants, be to mistake artistic practice in general as only a matter of ideology, rather than as a potential site for the eruption of truth.

This is why Supports/Surfaces could not bid painting adieu. To illuminate this perspective, I will quote at length from the introduction to the first issue of Peinture, cahiers théoriques:

The formal subversion inflicted upon the market by the fact that we insist upon working on “painting” as a relatively autonomous signifying practice that tracks alongside the material history which determines it in the final instance (in other words, is capable of modifying it, of running in advance or falling behind in relation to it, of having its own temporality), as opposed to the avant-gardist rejection of painting (non-art, production of objects playing out a total rupture with the history of painting up to the present, and thus leaving this history unthought), should coincide with the unveiling of painting’s specific logic as a signifying system. This objective scientific discovery strikes at the very core of the metaphysical framework that considers the signifying formations (literature, painting, etc.… ) purely as ideologies (the “artist” participates in ideology outside of his practice, but his practice is a specific space that should be distinguished from ideology and from science) as does mechanistic “Marxism,” or as ideas, as does transcendental philosophy—in short, as expressions of something already present, or as immanences. Mechanistic materialism and transcendental philosophy share the idealist belief in matter as inert and unformed, which the subject has therefore to “create.” The discovery of this logic specific to the painting system [au système peinture] renders academic and moot any representational mode of painting, whether as the reproduction of its own mode of production or as an image of an already-present reality, and gives rise to pictorial practice as the transformative production or non-production which exposes the work of production instead of real objects, inscribing itself within a dialectical process of knowledge that effaces the object produced and transforms it into an object of knowledge; transformative production giving way to a reading and not to a recognition [reconnaissance] of something always already there, as misrecognition [méconnaissance] of the manner in which “it” gets there [comme méconnaissance de la façon dont “ça” en vient là].[37]

There are many things happening in this tangled paragraph that are beyond the scope of the exposition I have offered thus far. It would be possible to dissect the notion of a “relatively autonomous signifying practice,” determined “in the final instance” by material history, in much greater detail, for example (these too are Althusserianisms); the word “ça” in the final paragraph in turn evokes the French translation of the Freudian es, or id, and hence the formation of the unconscious. The important thing to emphasize, though, is how the protagonists of Supports/Surfaces (in this case they are Vincent Bioulès, Cane, Devade, and Dezeuze, the members of the journal’s editorial committee) articulate the “logic” of painting with a rejection of “non-art” in a way that perhaps explicates their curious welding of a caustic Maoism to the most evidently conservative of artistic media. To condense greatly: the reason why this fusion works, or seemed to work at the time, is that a revolutionary, materialist approach to signification refuses to countenance the reduction of any signifying practice to something “already there,” and thus without need of further thought. Such an approach also resists the vulgar Marxist reduction of art to mere ideology. Art rather occupies a space somewhere between ideology and science. The time for painting’s liquidation, its reduction to mute objectivity, had not arrived.[38] It may never arrive, if we take seriously the infinite “deferral” that Devade perceived in the loop between painting’s surface and support. Comrade Mao was on the side of developing abstract painting’s specificity further, not of throwing it by the wayside. Or anyway the idea of a modernist and deconstructive Maoist abstraction seemed cogent enough in 1971.

For all their radicalism, this position has the potential to make artists-cum-theorists of Supports/Surfaces come off as aesthetically retrograde in comparison to some of their contemporaries. Duchampianism, Nouveau Réalisme, and Minimalism all looked to Devade and his companions like a premature surrender to what Michael Fried, albeit in a very different vocabulary, and for different reasons, called the “literalist” reduction of the artwork to objecthood—to the empirical existence of a thing, the qualities of which are available to the viewing subject in the real time and space of perception. Conceptual Art, to take another example, was for Supports/Surfaces a false “theoreticism” that aims to ground meaning in a priori propositions (in fact, unreflected commonplaces), as opposed to embarking on the dialectical labor of producing knowledge from an ideological field. Nothing is more mystified than that which presents itself as immediately knowable. In painting, “what you see is what you see” is thus the most ideological statement of all.

The quotation is from Frank Stella, Fried’s hero. This does not change the circumstance that Stella provided a 1960s catchphrase for the rejection of composition, or, we could say, of articulation, of the non-identity of the painterly mark with its literal facticity as a thing on the wall. Devade’s invocation of différance, of the “doubling” of the graphic and the chromatic, of surface and support, has no higher aim than to preserve the non-identity of painting (with itself or with anything else) against a collapse of painting into objecthood. The latter would be a collapse of the “object of knowledge” into the “real object” of empiricism, to return to Althusser’s terminology. Just as the object of knowledge must be produced, and thus becomes the lodestone of a semi-autonomous discipline, painting’s (semi-)autonomy had to serve as the precondition for its materialist practice. Autonomy is another name for non-identity, then. In Fried’s terms, autonomy is what holds off painting’s collapse into the “theater” that lies “between the arts.”

Needless to say, there are more than trivial differences of emphasis here. For one thing there is a difference between the dialectical, indeed Hegelian method of Fried and, before him, Greenberg, and the interminable deconstruction that Devade proposes under Derrida’s influence.[39] Yet it is striking to find any echo at all.

Via Fried, we are now in position to explain another surprising kinship, this time undoubtedly a conscious one.[40] Within its first three years, Peinture, cahiers théoriques published three translations of essays by Clement Greenberg: “Picasso at Seventy-Five” and “Master Léger” in issue 2/3 (spring 1972) and “Modernist Painting” in issue 8/9 (spring 1974). (The first two essays had appeared in Greenberg’s 1961 collection Art and Culture. One suspects they were chosen for translation ahead of the book’s more obviously programmatic texts because they are about totems of the École de Paris. “Modernist Painting” is the author’s best-known statement and hence its selection needs less explaining.) There are purely superficial reasons why Greenberg might have attracted interest from Supports/Surfaces. Their works at times look rather like the Color Field painting to which Greenberg turned his attention after the heroic days of Abstract Expressionism. The more important reason for this elective affinity, however, is that Greenberg seemed to Devade et al. to offer an account of painting’s specificity. This was not yet, at least in the eyes of Supports/Surfaces, the ossified “medium specificity” that was soon to be a favored target of the nascent postmodern movement, at least in the USA. I hope that I have already indicated the quite different sort of specificity that was here at stake: that of Althusserian theoretical practice. At the turn of ’70s, in France, it was possible and indeed, it seems, quite logical for a group of thinkers steeped in the work of Althusser, Derrida, Lacan, Kristeva, Sollers—and, not least, Mao Zedong—to read Clement Greenberg as someone fundamentally on their side.

“Modernist Painting,” for example, famously describes “the use of characteristic methods of a discipline to criticize the discipline itself, not in order to subvert it but in order to entrench it more firmly in its area of competence.”[41] Though “competence” is a word one seldom encounters in the universe of Supports/Surfaces, and though “subversion” was quite definitely on their minds, the thrust of Greenberg’s argument is in line with the account of materialist practice that I have summarized above. And it is also closer to a post-structuralist model of textuality, of “literary production,” than generally seems to be noted. Take Sollers, in Writing and the Experience of Limits (L’écriture et l’expérience des limites, published in 1968):

A COMPREHENSIVE THEORY [THÉORIE D’ENSEMBLE] DERIVED FROM THE PRACTICE OF WRITING DEMANDS TO BE ELABORATED. […] From the practice signifies that it has become impossible, beginning with a rupture that can be precisely situated in history, to make of writing an object that can be studied by any means other than writing (its exercise, under certain conditions). In other words, the specific problematic of writing breaks decisively with myth and representation to think itself in its literality and its space.[42]

To think writing “in its literality and in its space” echoes Fried’s assault on Minimalism. But the stress on the specific problematic of writing and its delinking from “myth and representation” (let us translate: narrative and theater) is also fully compatible with the Greenbergian paradigm. Although, granted, it is hard to imagine by whatother means one could study writing, Sollers’s insistence on writing’s self-interpretation is noteworthy, and stridently modernist.

Or take three sentences from Derrida in “The Double Session,” all in reference to Mallarmé: “Literature is at once reassured and threatened by the fact of depending only on itself, standing in the air, all alone, aside from Being”;[43] and: “The Mime mimes reference. He is not an imitator; he mimes imitation.”[44] The first is a free if unintended variation on the argument of “Modernist Painting.” The other two sentences are a near-paraphrase, surely even less intended, of a passage in Greenberg’s 1939 essay “Avant-Garde and Kitsch” about the practice of the modernist artist or writer: “And so he turns out to be imitating, not God—and here I use ‘imitate’ in its Aristotelian sense—but the disciplines and processes of art and literature themselves. […] If, to continue with Aristotle, all art and literature are imitation, then what we have here is the imitation of imitating.”[45] This might as easily have been written of Devade’s non-identical chromatic planes.

If this juxtaposition produces the slightest frisson, it is surely because Greenberg has long served as the avatar of a sort of painterly fundamentalism, a “medium specificity” that is, at first glance, the opposite of deconstructive play. I hope that what I have done in this essay shines a new light on both sides of the ledger. This may elucidate what is perhaps an even more confounding solidarity, that of deconstructive textuality with the politics of Maoist revolution. For if the specificity, the autonomy, of a discipline’s procedures is the guarantee of its materialist bona fides, then the coupling of a backwards-looking fidelity to the giants of high modernism (Matisse, Mallarmé) with fire-breathing Maoism makes a bit more sense.

My aim has not been to fit squares into circles. I do not mean to say that pairing Greenberg with Mao explains Supports/Surfaces in anything like an adequate way. Rather, the fact that it can be done at all, with any plausibility, is the strange datum that needs attention. Even in the special circumstances of the early 1970s, when failure on the barricades had been transmuted into a range of alternate strategies (or coping mechanisms: further street-fighting radicalization; a retreat from practice into theory; doublings-down on Marxism, or breakings away from it entirely; depoliticization, complacency, outright conservatism),[46] the chimera of a radically abstract Maoist painting was hard to maintain for very long. And like all varieties of Maoism it demanded intermittent purges.

Greenberg himself was one such victim, in 1974. The tone of Devade’s introduction to “Modernist Painting” in issue 8/9 of Peinture, cahiers théoriques is very different from that of the brief editorial notice that preceded “Picasso at Seventy-Five” and “Master Léger” two years earlier.[47] Devade here acknowledges that Greenberg’s Kantian method allowed him to “discover the autonomy and the specificity of art with respect to other symbolic forms in ideology.”[48] But the remainder of this incessantly hectoring text lambasts Greenberg for his evolutionist, empirical, and anti-dialectical approach. In essence, Greenberg fails to grasp the “qualitative leap” of the Cézannian rupture and acknowledges neither the unconscious nor language as the material grounds of subjectivity. In other words, he fails to be a Tel Quelian.

Devade however soon makes a rather jarring leap from the usual Althusserian-Maoist-Lacanian tropes—an orthodoxy that of course makes sense only in the very peculiar moment of the early ’70s—to a new language of psychosexual “pulsion.” Deleuze and Guattari’s “body without organs” makes a cameo. His main points of reference, though, are Kristeva’s and Sollers’ contributions to a 1972 Tel Quel conference on Georges Bataille and Antonin Artaud, which took place in the little Norman town of Cerisy-la-Salle. (I have already cited Kristeva’s text, “The Subject in Process,” above.) This event marked a threshold in Tel Quel’s development. Although the Maoist infatuation would persist for another four years, from that moment on the group’s theory increasingly focused on Freudian drives, transgression, and abjection. Sollers and Kristeva had their own reasons for this shift in focus. But in Devade’s case, one may conjecture, the utility of the libidinal turn may have been more straightforward. In effect, it enabled him to fit the square peg of “relative autonomy” into the round hole of historical materialism, via a turn to the constitution of (the artist’s) subjectivity. The problem with Greenberg, and evidently with American artists and critics in general, is that they are fetishists: fetishists of painting, fetishists of medium specificity, fetishists of the commodity. Devade is not above the homophobic suggestion that Greenberg et al. are stuck in an anal or oral stage, rather than having developed healthy genital jouissance. Properly materialist painting and criticism, by contrast, undoes fetishization in favor of a veritable tide of chromatic-libidinal pulsion (color, for Devade, being by this stage understood as hardly less than desire manifest in painting). And since an account of the pulsional constitution of subjectivity—the painter’s, as well as everyone else’s—by way of desire and language simply is materialism, there is no longer any need for political translation: no need to bother with messy mediations between theory and practice. An account of art that looks suspiciously like the Expressionist ur-trope of art-as-exposition-of-the-unconscious effectively assumes the use-value previously accorded to Althusserian theoretical practice. The base, Bataillean materialism of Devade’s “painting seen from below” has here become practically a closed loop between the painter and his own desire, this evidently being enough to maintain radical cachet. Devade’s Maoist rhetoric is still virulent as ever. But by 1974 the exit sign was flashing.

Coda

All of which leaves us with the problem of what to make of a practice and theoretical discourse that more or less erased its own (political) justification over the decade following 1968. I have already hinted at one response: to let theory and politics drop out of the picture altogether. As a market for abstract painting reemerged in the 21st century (not that it had ever gone far underground), so too did interest in Supports/Surfaces. An early flash was the exhibition As Painting: Division and Displacement, which Stephen Melville, Laura Lisbon, and Philipp Armstrong organized at the Wexner Center for the Arts in 2001. The show and its catalog prominently featured the group as part of a broader strain of post-World War II experimental painting. Another important text, more or less contemporaneous with the Wexner exhibition, was Howard Singerman’s article “Noncompositional Effects, or the Process of Painting in the 1970s.”[49] After this brief renaissance, however, scholarship on Supports/Surfaces has been slow in coming, at least until now. In the 2010s the reception of this work instead occurred in the penumbra of quite a different phenomenon: namely, the market success, and then failure, of a revivified “process-oriented abstraction,” or, as it has been more colloquially known, “zombie formalism,” “crapstraction,” etc.[50] This is not an association anyone would envy.

If the work of Supports/Surfaces is to mean anything in the future, this cannot be its frame of reference. Some of the original stakes will have to be recovered. And that means, above all, the recovery of politics. Nothing so obtuse as a defense of their Maoism, or for that matter of their paintings, need be on the table. It is rather that we could stand to take seriously the entanglement of a specific set of (modernist) practices with the rise and fall of a revolutionary movement. After all, the story of May ’68 is to a large extent the story of its eclipse at the hands of friends and enemies alike. Absurdity and irresolution are part of that dialectic, but so, too, are certain achievements (formal, theoretical) that may yet prove more difficult to revoke. Perhaps the best way to recover the radicalism of Supports/Surfaces is through what we might call a principle of methodological irony. Supports/Surfaces was, and was not, “genuinely” revolutionary; it was, and was not, genuinely collective, just as Devade’s theory did, and did not, speak for his comrades. Historians have little right to lay down normative judgments, of political sincerity for example. Our task is rather to grasp the conditions of possibility for a given set of practices or discursive formations. Acceptance of that role does not however exclude partisan interest in retrieving some of what remained unfulfilled, and thus generative, in a given moment that we now have no choice but to view in parallax—that is, from the present. We ought to know, of course, that history does not deliver pristine models; every discursive and formal complex that has come down to us is a product of an irrecoverable conjunction of conflicts, tensions, and tendencies that eventuated in this set of forms and no other. Which is not to say that that there are no lessons for the taking. Supports/Surfaces was a shape of its time: hardly one without contradictions.

So here is the sticking point. Drawing water from the same well, and reaching a few similar conclusions, these artists and thinkers independently produced a discourse loosely akin to Greenbergian-Friedian formalism, a discourse that was allied, however, not to a last-ditch defense of aesthetic quality, and of the bourgeois culture to which that notion is bound at the hip, but rather to communist revolution. It is this position that soon became illegible, even to its own protagonists. Or legible only as bad faith.[51] Only two things needed to happen. First, Greenberg and by extension modernism as a whole had to be pushed into the wastebasket of history. And second, the memory of May ’68, in its true extremity and threat, had to fall into disrepute, or just oblivion. Half a century later, what remains vital in Supports/Surfaces, and what might be held onto for the future, is exactly what is most strained and tenuous in their legacy—their modernism-at-the-breaking-point. Or to appropriate Derrida a final time: a modernism without reserve.[52]

- [1] Theodor Adorno et al., The Positivist Dispute in German Sociology, trans. Glyn Adey and David Frisby (London: Heinemann, 1976), 34.

- [2] Yve-Alain Bois: “If the corpse of Supports/Surfaces must be exhumed, it is better to let its texts remain in abeyance, if only for a little while.” Bois, “Les Années Supports/Surfaces,” Artforum International, vol. 37, no. 4 (December 1998), 120.

- [3] On Althusser’s influence, compare Sami Siegelbaum’s essay in the present issue of Selva.

- [4] Saytour, for example, was interested in the siting of his cloth-based works in non-traditional contexts—often out of doors—in a manner that has something in common with American Land Art of the period, or with Christo’s fences and wrappings. Such preoccupations were of little import to the Peinture editorial group. As the journal’s very name indicates, they were rather concerned—almost myopically—with the medium of painting per se. Photographs of early Supports/Surfaces group exhibitions reveal a preponderance of sculpture, or at least of three-dimensional objects, that one could hardly extrapolate from the pages of Peinture, cahiers théoriques.

- [5] In this context, the noun “problematic” should be understood in the sense it acquired in French thought after the publication of Gaston Bachelard’s book Le rationalisme appliqué (Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1949), and then most influentially in Althusser’s materialist epistemology of the early to mid-1960s. For a précis of Bachelard’s book as well as concise reflections on the notion of the “problematic,” see: Patrice Maniglier, “What is a Problematic?” Radical Philosophy 173 (May/June 2012), 24-26.

- [6] The first issue of Tel Quel to appear after the upheaval essentially presents an oblique version of the Party’s official line. A text in this issue (“La révolution ici maintenant,” Tel Quel 34 [summer 1968], 4-5) defends a rigorously theoretical rather than politically engaged research program.

- [7] “[…] devant l’inflation des pratiques individuelles névrotiques soutenues par le marché de la peinture et sa presse, la fondation de ce groupe fut un acte positif de défense active d’un certain type de peinture comme pratique théorique, comme pratique matérialiste spécifique, malgré des effets empiriques. Il constitue ainsi la base d’appuie essentielle pour un certain nombre de peintres ayant pour visée non seulement la transformation de leur pratique, mais à travers elle la transformation du champ économique et social qui les conditionne; transformation qu’aucune pratique de type individuel ne peut prétendre opérer efficacement, même si elle se maquille d’emprunts théoriques.” Devade, “Pourquoi un revue?” VH 101 5 (Spring 1971), 83.

- [8] Louis Althusser, “From Capital to Marx’s Philosophy,” in Althusser and Étienne Balibar, Reading Capital, trans. Ben Brewster (London and New York: Verso, 1997), 18. Althusser’s notion of the “epistemological break” is borrowed from Gaston Bachelard and, less obviously, from a broader tradition of French rationalism in the philosophy of science (Georges Canguilhem, Jean Cavaillès, and Michel Foucault are the key points of reference). In the mid- to late ’60s, the rationalist strain of Althusserian / Lacanian thought possessed a bastion in the journal Cahiers pour l’analyse. Over the past decade this tendency has reemerged as a counterpoint to the so-called “linguistic turn”; see especially: Knox Peden, Spinoza contra Phenomenology: French Rationalism from Cavaillès to Deleuze (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2014). Cahiers pour l’analyse was one of the models for Peinture, cahiers théoriques itself. Dezeuze, for example, mentions it in the introduction to his collected writings, at the same time noting that his membership in the PCF (Communist Party of France) from 1969 to 1971 took place “under the illusion that the Althusserian current could maintain itself”: Dezeuze, Écrits, entretiens, poèmes, 1967-2008 (Paris: Beaux-arts de Paris, 2008), 22.

- [9] It is possible to read this pattern of rupture/repetition as another approach to the familiar dilemma of the so-called “neo-avant-garde,” as this term has been used in the work of Peter Bürger, Benjamin Buchloh, Hal Foster and others since the 1970s.

- [10] “C’est le degré zéro de la peinture: la mise en évidence de ses constituants devient le propos même de l’oeuvre et ils sont exploités de façon à réveler leurs caractères et leurs effets propres.” Millet, preface to Nouvelle peinture en France: Pratiques, theories (Saint-Étienne: Musée d’art et d’industrie, 1974), 6. Writing in 1974, and thus in what had already become a retrospective account, Millet names the two main factors that led to the emergence of Supports/Surfaces as a coherent formation at the end of the previous decade: first, an awareness of American painting (she notes the influence of the 1968 exhibition L’art du réel: USA 1948-1968, at the Centre National d’Art Contemporain, Paris), and second, the encounter with the Tel Quel group. She also here usefully summarizes their aims, namely: “attachment to a rigorous definition of the specific elements of painting, but also an attempt to escape the rather sterilizing formalism that the Americans, despite their progressive approach, had instituted.” (Ibid.) As we shall see, Devade had come to a similar conclusion about American “sterility” at around the same moment.

- [11] In the first issue of Peinture, cahiers théoriques, the editorial committee lists “Chinese thought and writing” alongside “experimental practice,” “linguistics, semiotics,” “Marxism-Leninism,” “psychoanalysis,” and “Mao Zedong Thought” as the ingredients of the group’s synthesis. Chinese characters pop up frequently in Sollers as well as in the pages of Peinture during this period and continue to do so up through Tel Quel’s break with Maoism in 1976. The authors, remarkably, assume a continuity from classical Chinese art and philosophy to Maoist doctrine, moreover at the precise moment when the Cultural Revolution was liquidating much of that heritage; see, for example, Devade’s “Notes préliminaires, ou comment voir la Chine en peinture,” Peinture, cahiers théoriques 2/3 (Spring 1972), 75-87, which juxtaposes quotations from Zhuang Zhou, Hui Shi, and other classical Chinese authors with quotations from Mao and Georges Bataille. Tel Quel’s attraction to Chinese script was premised on its non-phoneticism. Derrida himself lent some support to the idea that Chinese writing escapes the phonocentrism of Western metaphysics; in Of Grammatology, for example, he devotes several pages to “largely nonphonetic scripts like Chinese and Japanese,” which are “testimony of a powerful movement of civilization developing outside of all logocentrism.” (Derrida, Of Grammatology, trans. Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak [Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins Univeristy Press, 1974], 90; incidentally, Derrida’s failure to differentiate the Chinese logographic writing system from Japanese, which in fact combines logographic kanji with syllabic kana, indicates some of the confusion in Western views of Asian languages even at this late date.) Sollers, who together with Kristeva made an effort to learn Chinese, went so far as to translate some of Mao’s poems. (“Dix poèmes de Mao Tsé-Toung,” Tel Quel 40 [Winter 1970]; reprinted in: Sollers, Sur le matérialisme [Paris: Éditions du Seuil, 1974].)This infatuation with ancient Chinese dialectics, founded as it was on limited access to Chinese literature and a blinkered view of the Cultural Revolution, deserves more attention than I can pay it here. A significant number of articles in Peinture, cahiers théoriques mention Chinese painting; issue 4/5 (Spring 1972) also devotes about thirty pages to translations of “textes philosophiques de Chine Populaire,” in conjunction with a Tel Quel double issue on China (no. 48/49, Spring 1972).

- [12] Devade, “Chromatic Painting: Theorem Written through Painting,” trans. Roland-François Lack, in Patrick ffrench and Roland-François Lack, The Tel Quel Reader (London and New York: Routledge, 1998), 181-197; originally published in Tel Quel 41 (Spring 1970).

- [13] “Chromatic Painting,” 183.

- [14] Translation modified from: “Chromatic Painting,” 183; emphasis in the original. Devade’s article is divided into numbered sections, somewhat like Spinoza’s Ethics; the propositions I have just quoted are numbers 2.4, 2.7, and 2.7.1. Lack’s translation consistently uses the word “pictural” rather than “pictorial” as an equivalent for the French pictural. Picturalis an everyday word in French, whereas “pictural,” in English, is not. Here and elsewhere I therefore change Lack’s “pictural” to “pictorial,” for simplicity’s sake and to avoid having to explain a terminological distinction that does not actually exist (or at any rate does not exist so clearly) in the original text. I have however maintained Lack’s British spellings in my quotations.

- [15] Cf. Goux, “Marx and the Inscription of Labour,” in The Tel Quel Reader, 50-69; originally published in Tel Quel 33 (Spring 1968).

- [16] “Chromatic Painting,” 195.

- [17] Egenhofer, Towards an Aesthetics of Production, trans. James Gussen (Zürich: Diaphanes, 2017); Egenhofer, Abstraktion – Kapitalismus – Subjektivität. Die Wahrheitsfunktion des Werks in der Moderne (Munich: Fink, 2008). I have a written a review of both books: Daniel Spaulding, “Orders of Appearance,” Oxford Art Journal, vol. 42, no. 2 (fall 2019), 406-412.

- [18] “Chromatic Painting,” 184.

- [19] Devade’s approach to illusion is easy enough to comprehend in terms of a then-developing discourse in post-structuralism. To take one of many possible quotations from Derrida’s reading of Mallarmé in “The Double Session”: “This speculum reflects no reality; it produces mere ‘reality effects.’ […] Mallarmé thus preserves the differential structure of mimicry or mimesis, but without its Platonic or metaphysical interpretation, which implies that somewhere the being of something that is, is being imitated.” Derrida, Dissemination, trans. Barbara Johnson (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1981), 206; emphasis in the original.

- [20] To anticipate some concerns that will recur below: it is the painterly mark, which Devade happens to conceptualize in terms of color, that wards off the specter of the “stretched or tacked-up canvas” that for Clement Greenberg “already exists as a picture—though not necessarily as a successful one.” To this, Michael Fried notoriously replied that it would be “less of an exaggeration to say that it is not conceivably one.” The first quotation is from: Greenberg, “After Abstract Expressionism” (1962), in The Collected Essays and Criticism, vol. 4, ed. John O’Brian (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993), 131-32; the second is from: Fried, “Art and Objecthood” (1967), in Art and Objecthood: Essays and Reviews (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 1998), 169; emphasis in the original in both cases.

- [21] Devade, “Chromatic Painting,” 184-85. “Equivalence” and “identity” admittedly do not seem like exactly the right words here if Devade is aiming to keep faith with Derrida; “undecidability” would be more on the mark. We can perhaps credit the newness of the terminology for these wrinkles.

- [22] Ibid., 192. Devade’s use of the term “archi-painting” predates Yve-Alain Bois’s development of the term “arche-drawing.” Cf. Bois, “Matisse and “Arche-drawing,”” in Painting as Model (Cambridge, MA, and London: The MIT Press, 1990), 3-63.

- [23] In an important essay, Stephen Melville associates this self-generation with the idea that “matter thinks.” Melville, “Counting /As/ Painting,” in Melville, Philipp Armstrong, and Laura Lisbon, As Painting: Division and Displacement (Columbus, OH: Wexner Center for the Arts, 2001), 6. The Supports/Surfaces-affiliated critic Marcelin Pleynet published an essay on Artaud entitled “La Matière pense” in Tel Quel 52 (Fall 1972); Melville’s phrasing also evokes Hubert Damisch’s oft-repeated claim that “painting thinks.” In the present context I would however slightly amend Melville: for Devade, at least, it is perhaps not so much that matter thinks, in the way human beings are generally taken to do, but rather that the (inhuman, autonomous) signifying chain produces as its effects both “subjects” and “meaning.” It is not that matter thinks, then, so much that thinking is material, perhaps disconcertingly so.

- [24] Kristeva, “The Subject in Process,” trans. Patrick ffrench, in The Tel Quel Reader, 133-178. This paper was originally delivered at a 1972 Tel Quel conference on Antonin Artaud and Georges Bataille, about which there will be more to say below. On “chromatic libido” in the work of Supports/Surfaces artists after 1972, compare Jenevive Nykolak’s essay in the present issue of Selva.

- [25] “Chromatic Painting,” 186.

- [26] “Chromatic Painting,” 183. Devade’s “format” perhaps anticipates the concept of “apparatus” that was soon to emerge in film theory under the influence of Lacan and Althusser. At issue in both cases are the technical parameters of a signifying practice that generates a specific subject-effect. Perspectival totalization in Western painting is comparable to the “suture” of narrative cinema. This convergence with Supports/Surfaces is hardly coincidental. In his influential 1976 article on “Narrative Space,” for example, Stephen Heath quotes a 1969 interview with Marcelin Pleynet in which the Tel Quel and Supports/Surfaces-aligned critic identifies the camera’s eye with Renaissance monocular perspective (“a camera productive of a perspective code directly constructed on the model of the scientific perspective of the Quattrocento”): Heath, “Narrative Space,” Screen, vol. 17, no. 1 (October 1976), 75; the quotation is from: Pleynet, “Entretien” (with Gérard Leblanc]), Cinéthique 3, 1969. The journal Cinéthique, from which Heath is quoting, was another Tel Quel offshoot of the period, this one (naturally) concerned with film. I can only gesture towards this milieu’s engagement with perspective and early Renaissance painting circa 1972; important documents here are Kristeva’s “L’espace Giotto,” originally published in Peinture, cahiers théoriques 2/3 (1972) and subsequently published as “Giotto’s Joy” in: Kristeva, Desire in Language: A Semiotic Approach to Literature and Art, trans. Thomas Gora and Alice A. Jardine (New York: Columbia University Press, 1982), as well as Daniel Dezeuze’s condensed, almost hallucinatory text “Quattrocento’s Feedback,” also from 1972, in: Dezeuze, Textes, entretiens, poèmes, 1967-2008 (Paris: Beaux-arts de Paris, 2008), translated in the present issue of Selva: Dezeuze, “Studio Notes,” trans. Daniel Spaulding, Selva: A Journal of the History of Art 1 (fall 2019), 78-80.

- [27] Ibid., 183. The text Devade is quoting is Mondrian’s “Natural Reality and Abstract Reality” of 1919.

- [28] First version published in two parts in Critique 261 (February 1969) and 262 (March 1969); reprinted in: Derrida, Dissemination, 287-366.

- [29] In particular, refer to Althusser’s critique of empiricism in Reading Capital, 36-49.

- [30] Jacques Lacan, The Seminar of Jacques Lacan, vol. XX, On Feminine Sexuality: The Limits of Love and Knowledge, trans. Bruce Fink (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1998), 93.

- [31] Miller, “Action of the Structure,” trans. Christian Kerslake, in Peter Hallward and Knox Peden, Concept and Form, vol. 1, Key Texts from the Cahiers pour l’Analyse (London and New York: Verso, 2012), 69-83; originally published in Cahiers pour l’analyse, vol. 9, no. 6 (Summer 1968), 93-105. Although published in 1968, the essay bears the date 1964.

- [32] Concept and Form, vol. 1, p. 38. “The lack of a lack is also a lack” is a quotation from Miller’s “Action of the Structure,” 80.

- [33] Miller, “Action of the Structure,” 80.

- [34] The difficulty here is that Althusser has generally been read as identifying ideology with Lacan’s imaginary. But the development of Althusser’s concept of ideology is considerably more complex than this, as Warren Montag has shown, and in any case there is hardly a hint in Althusser’s pivotal works of the 1960s (from For Marx to “Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses”) that there exists anything like a non-ideological “real” directly available to science as its material. See: Montag, Althusser and His Contemporaries: Philosophy’s Perpetual War (Durham, NC, and London: Duke University Press, 2013).The real is precisely that which poses an “impasse” to formalization, and thus structures it; science does not deny lack but rather explicates a specific discursive field as structured by a specific lack or absence. And it is lack that—again in Jacques-Alain Miller’s extrapolations from Althusser and Lacan—triggers the “suture” of imaginary/ideological identification, and thus subjectivation: a subject is always a subject of lack.

- [35] See for example the introductory statement by the editorial committee in Peinture, cahiers théoriques 1 (1971), 7-12 (published in translation in the present issue of Selva, pages 87-90), in which the editorial committee (Bioulès, Cane, Devade, and Dezeuze) assert that the review’s impact is limited to the “specific contradiction which forms its object: painting.”

- [36] Devade’s description of painting as a “theoretical practice” is probably illicit in strict Althusserian terms, however. Althusser seems to reserve that concept rather narrowly for theory proper, rather than creative or poetic disciplines (there is no comparable suggestion that the writing of novels, for example, might constitute a theoretical practice).

- [37] “Statement by the Editorial Committee,” Selva 1, 88.

- [38] Another pair of authors in the Supports/Surfaces orbit, writing in a catalog essay of 1974, phrased this idea in language that interestingly recalls Guy Debord’s observation, in The Society of the Spectacle, that “Dadaism sought to abolish art without realizing it,” while “Surrealism sought to realize art without abolishing it”: “What is necessary now is a critical return to the history of art so that practice may escape the double danger of idealism and its inverted image: Dadaist negation and its utopian pretense of suppressing art without having first realized it.” (“Est alors nécessaire un retour critique sur l’histoire de l’art pour que la pratique puisse échapper au double danger de l’idéalisme et de son image renversée: la negation dadaïste et sa prétention utopique à supprimer l’art sans l’avoir au préalable réalisé.”) Jacques Beauffet and Bernard Ceysson, Nouvelle peinture en France: Pratiques, theories (Saint-Étienne: Musée d’art et d’industrie, 1974), 5. As Pattrick ffrench notes, Tel Quel is completely devoid of references to the Situationists. (ffrench, The Time of Theory, cited above, 11.) From the 1980s onward, however, Sollers was to engage with Debord’s work, much to Debord’s chagrin. For Debord’s opinion of Sollers, see, for example, his letter to Gérard Lebovici of June 23, 1977, or to Annie le Brun on November 5, 1992, in: Guy Debord, Correspondance, ed. Patrick Mosconi (Paris: Fayard, 1999-), vols. 5 and 7, respectively.

- [39] Fried has been clear about the Hegelianism of his early writings. See, for example, his reference to “the joint influence on me of Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s remarks on Hegel in his essay ‘Indirect Language and the Voices of Silence’ and of Georg Lukács’s History and Class Consciousness.” (“An Introduction to my Art Criticism,” in Art and Objecthood, 18.)

- [40] I have found no evidence that either the Tel Quel group or the members of Supports/Surfaces engaged with Fried’s writings in this period. I believe the resonances to which I have drawn attention are explained in part by shared genealogy (namely Greenberg) and in part by convergent evolution—that is, a shared commitment to the specificity of modernist practices, in resistance to the blurring of boundaries in Nouveau Réalisme, Minimalism, Pop Art, etc.

- [41] Greenberg, The Collected Essays and Criticism, vol. 4, ed. John O’Brian (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 1993), 85.

- [42] Sollers, “Program,” in Writing and the Experience of Limits, trans. Philip Barnard and David Hayman (New York: Columbia University Press, 1983), 5. The French in brackets is in the original, as is the emphasis, needless to say.

- [43] Derrida, Dissemination, 280.

- [44] Ibid., 219.

- [45] Greenberg, The Collected Essays and Criticism, vol. 1, ed. John O’Brian (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 1986), 8-9.

- [46] Cf. Peter Starr, Logics of Failed Revolts: French Theory after May ’68 (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1995).

- [47] Marc Devade, “La peinture vue d’en-bas,” Peinture: Cahiers théoriques 8/9 (Spring 1974), 19-31. The second text that Devade here presents (and savages) is an essay on Robert Mangold by Diane Waldman. His criticism of Waldman is hardly distinguished from that of Greenberg, so I will not discuss it. Devade’s text is dated October 1973, although the issue did not appear in print until the spring of the following year.

- [48] Ibid., 20.

- [49] Oxford Art Journal, vol. 26, no. 1 (2003), 127-150.

- [50] Jerry Saltz lists these and yet more terms: Saltz, “Zombies on the Walls: Why Does So Much New Abstraction Look the Same?” (Vulture, June 17, 2014), http://www.vulture.com/2014/06/why-new-abstract-paintings-look-the-same.html (accessed 10/20/2018).

- [51] In the final 1979 issue of the journal Macula, Yve-Alain Bois and Jean Clay reproduced a specimen of Supports/Surfaces rhetoric under the heading “Seven Years Ago…”: “Down with the capital of art dealers and exploiters. Down with the state of capital. Long live the class struggle of artists and intellectuals. Long live the revolutionary struggle of the proletariat.” The slogans are taken from a tract signed by Supports/Surfaces and Peinture, cahiers théoriques that was distributed at the exhibition Douze ans d’art contemporain en France in May 1972. As Bois and Clay note, “This tract and its like did not appear at the exhibition ‘Tendances de l’art en France 1968/1978’ presented last September at the Musée de la ville de Paris (ARC).” The artists of Supports/Surfaces instead had a place of honor in that show. In other words, institutionalization had occurred. (Bois and Clay, “Quelques aspects de l’art récent: Introduction,” Macula 5/6 [1979], 193.)

- [52] Cf. Derrida, “From Restricted to General Economy: A Hegelianism without Reserve,” in Writing and Difference, trans. Alan Bass (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1978), 251-277.