Ideology, Strategy, Aesthetics

Ideology is the word that Marxists use to name divergences between cognition and reality that are more systematic than contingent error. The term has other meanings (most notably as a synonym for “worldview,” “set of beliefs,” or “political orientation”), but since it is the broadly Marxist or Marxian understanding of ideology that is at stake here, it seems right to linger with it and try to figure out how, or if, this concept might be relevant to the interpretation of artifacts such as paintings and sculptures. The possibility that cognition and reality may diverge implies that, potentially at least, they may also coincide or correspond. Hence the notion of ideology casts as its shadow the possibility of accurate knowledge of reality through science, revelation, aletheia or disclosure, or another kind of truth, as well as the possibility that no such knowledge is possible and hence that there is no “outside” to ideology, perhaps for the simple reason that humans do not have unmediated access to reality. This small set of positions effectively exhausts the epistemological premises of the past century and a half’s worth of Marxist inquiry into the topic.[1]

The richness of this tradition is not found in the what of ideology but rather in the how. How are ideological concepts of or relations towards reality formed, and who or what does the forming? Does ideology serve the reproduction of social classes and relations of production? If so, how important is it—are ideological disputes confined to the “superstructure,” or can they trigger change in the “base”? Can any social formation get along without ideology? Is non-ideological knowledge possible—from what standpoint, by means of what technique or practice? And finally, what role might art and culture play in either the perpetuation or the undoing of ideology? Does it make most sense to say that art is ideology, or works upon ideological material, or is something else altogether (for example, the elaboration of a truth procedure)?

These last three possibilities remain within a Marxist lineage, broadly speaking, and can be associated with proper names. The notion that art is ideology, at least much of the time (that art materializes interpretations of the world that represent the interests of a social class or another group, such as straight white men), was once widespread among Marxist art historians and to a lesser degree in the discipline at large, as a consequence of the diffusion of ideas along these lines in the “New Art History” of the 1970s and ’80s.[2] The notion that art works upon ideological material, transforming it in the process, is developed in the early writings of T.J. Clark.[3] The notion that art is a “truth procedure” (along with love, politics, and science) is Alain Badiou’s and indicates that art breaks with ideology, at least when it is doing what it should.[4]

In general terms if not specifics, the latter approach is most congenial to current practice in the discipline. Art historians usually valorize their objects of study, both because this is more psychologically tolerable than studying harmful things and for reasons of self-promotion. Since the world is manifestly bad, this means that art worth writing about is generally taken to advance a critique of the world. (This is admittedly most pronounced in contemporary art history, whereas symptomatic reading—the analysis of works of art for what they unintentionally reveal about conflicts or contradictions in a given cultural setting—remains more common in other subfields.) However, this tendency to focus on the critical, ideology-busting function of art is in tension with the predominant culturalist framework of art historical research, in which an interpretation is held to be correct if it convincingly reconstructs an imputed normal usage or meaning of an artifact within “its” context—the world or community to which it belongs or once belonged.[5] That is, a tendency to valorize artifacts for their capacity to criticize social reality is at odds with a tendency to derive meaning from social context. The latter approach furnishes no Archimedean point from which such a critique might be posed, other than normative juxtaposition of the researcher’s values with those of the collectivity towards which an artifact is or was originally oriented. There may be no reason to avoid normativity; for example, there may be nothing wrong with observing that an early modern artwork is complicit with a colonial project that now clearly seems evil. But saying as much, unabashedly, is an affront to contextualist doxa.

This perhaps accounts for two further related tendencies in art historical writing of the early twenty-first century: first, to valorize artifacts that have a “proper” use or meaning immanent to a collectivity that is itself oppositional with respect to another, presumptively bad collectivity (as in the art of queer communities or people of color in opposition to heteropatriarchal racial capitalism, or whatever one wants to call the bad object here), and second, to reject or modify the paradigm of critique in favor of “reparative reading” or one of several other “post-critical” approaches.[6] These ways of thinking restore an immanence that renders ideology critique superfluous, since ideology critique operates by identifying contradictions between the values that a collectivity claims to uphold and its practices. (Most paradigmatically, the bourgeoisie proclaims that “all men are created equal,” yet produces inequality.)[7] If the social is split between, on the one hand, collectivities to which belong transparently good works of art—for example, works adequate to a good collectivity’s need for self-representation—and, on the other hand, a transparently bad order with which these works of art have little relation other than one of resistance (however notional), then there is not much room for ideology in art history at all. To take this line of thinking to its reductio ad absurdum: there is no room for immanent critique of an artwork if the very act of selecting an artwork for analysis extracts it from bad entanglements. Not coincidentally, one suspects, this logic is convenient for writing wall labels and press releases.

The point of my introduction to this issue of Selva is not to complain about this state of affairs, much less to demand a restoration of Marxist orthodoxy, but rather to ask whether the concept of ideology has anything left to offer enemies of the present order of things. Since this is fundamentally a journal of the history and historiography of art, in the first instance I address these words to art historians who recognize themselves in my previous sentence. However, it is unnecessary if not detrimental to insist that the (mostly rather annoying) figure of the “radical academic” has any special pertinence to these questions. This is because the relation between academia and social struggle has changed since the previous formalization of ideology theory in the post-New Left 1970s. These days, the notion that any academic in the humanities might exert real power, except in the specific, sad form of power over other academics (or academics-to-be), feels obviously absurd. It probably does not matter very much whether a given professor cleaves to one or another slightly different articulation of academia’s liberal consensus. Younger humanists will never have to worry about becoming public intellectuals.

Yet at the same time the global capitalist order has been volatile in the extreme, with unexpected mass movements erupting and being snuffed out at rapid intervals; overeducated and underemployed young people have been actors in these revolts nearly everywhere they have happened (most recently in China and Iran).[8] It would be entirely ordinary for an “emerging scholar” in the United States to have participated, successively, in demonstrations or building occupations in resistance to university fee increases in 2009, the Occupy movement in 2011, marches in protest of the police murder of Michael Brown in 2014 (or many protests of many other police murders of Black people over the same years), the Women’s March in 2017, and the uprising for Black lives in 2020—without ever having participated as a scholar, exactly. Ripples from these events generate scholarship as well, as we have seen in the proliferation of art historical reflections on monuments that was the mediated result of a straightforward need to destroy symbols of racism.[9] But it is unclear why an art historian’s thoughts on a statue of a slave trader or Confederate general ought to count for more than those of anyone who walks by such objects on a daily basis, and indeed from a certain point of view initiatives of this sort could be taken as a desperate grasp for relevance on the part of a discipline that usually lacks obvious wedge issues. The sincerity of art history’s monument-critics is not in question here, only the nature of the conveyor belt between anti-racist struggle and academic production that implicitly validates their interventions. In every instance, the statues came down without waiting for an art historian to give the green light.[10]

This is as much to say that the New Left’s aim of fighting “the class struggle in theory” (or the anti-racist struggle in art history, or the feminist struggle in comparative literature, etc., etc.), as Louis Althusser put it, perhaps no longer makes a great deal of sense.[11] More than the general decline of Marxism after the fall of the Berlin Wall, this is what separates us from the academic politics of the New Left, with its strategy of seizing the commanding heights of the ivory tower: “bereft of a common stake in the academy, we are compelled to struggle from outside its protectorate—not as ‘academic workers,’ but simply as comrades.”[12] Struggles within the university, when they are not just culture war froth, have the same stakes as struggles elsewhere: the reproduction of the capital-labor relation, with revolt often exploding along the seams of the proletariat’s segmentation by race and gender. In sequences such as the 2022 strikes at the New School and the University of California system, still ongoing as I write these lines, a more traditional union bureaucracy and socialist Left stands against kinds of action that would tend “to spread the strike and to generalize its disruption in the daily functions of the university … to interrupt not only the reproduction of the university as an institution, with its ledgers, budgets, and balance sheets, but the reproduction of this particular social division of labor and of the capital-relation itself,” as some anonymous authors have recently put it.[13] This is, of course, a tall order, and in an immediate sense most of my readers surely belong on the side of the ledger that stands to gain from the university’s survival rather than its destitution, inasmuch as we are reliant on it for wages, stipends, and health insurance (though in the longer term nothing that people need to thrive should be dependent on employment status). Anyway, this is where the fault line runs.

In such circumstances, it is unclear how or if a critique of the ideological content of works of art, launched from within the university, relates to a critique of the university as an institution that does its part to reproduce a bad world. And this is the crux of asking, as a journal issue on the topic must: Why ideology? Why ideology now? Why not now, when the baroque absurdities of QAnon have emerged as a historical force—when the will to disbelieve fact seems unshakeable amongst large segments of the US (and not only the US) populace? What to make of a situation in which such excrescences seem almost wholly surplus to the needs of capital accumulation: when even Thatcherism only persists as an ideological albatross around capitalism’s neck, as the brief inglorious tenure of Liz Truss has made clear, while corporations rally to the Democratic Party’s so-called “woke” agenda (a spray of social justice buzzwords over business-as-usual)? What to make of the circumstance that the art world and academia, in the humanities, at least, now march in more total political lockstep than at any point during the past two centuries, with little apparent effect on politics at large except to provide conservatives with a useful bogeyman? Is there any payoff for insisting on hoary concepts like “ideology” or “hegemony,” aimed, as they seem to be, at some probably impossible enlightenment of the public sphere, or should we just get down to the nastier work of strategy, not to say conspiratorial plotting—more Sun Tzu or Clausewitz, less Althusser and Žižek? In art history, unfortunately, much recent discourse on class and class ideologies has been confined to an arid debate over the “professional-managerial class” (or PMC, to which most parties in the dispute self-consciously belong) and its relation to contemporary art.[14] We deserve better. Most of the articles that follow do not explicitly touch upon art or art history at all, but in sum they ought to provide materials for an art history to come.

To begin with, it should be said that this issue of Selva is agnostic regarding the utility, the definition, and maybe even the existence of its object. The textual basis in Marx’s corpus for all subsequent Marxist ideology theory is thin, amounting to not much more than a few sentences in the preface to his Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy and, of course, The German Ideology, which he wrote with Friedrich Engels, plus implications that can be drawn from some of his political writings and comments on bourgeois economists, in which the term is very rarely encountered verbatim.[15] “Ideology” as we know it is essentially a creature of the Second and Third Internationals, and from a certain point of view—which might be dubbed ultra-leftist or anarchist, depending on who is doing the talking—its use-value in left-wing politics has been to shore up the Leninist claim that the masses are incapable of achieving revolutionary political consciousness (of transcending their spontaneous “trade-union consciousness” of economic interests) without guidance from a revolutionary intelligentsia in possession of revolutionary theory.[16] A few important Marxists have denied this for the past century.[17]

If not confined to noting the idiocies of bourgeois theorists, a strictly Marxian ideology problematic—meaning, a problematic that sticks to what Marx wrote, rather than what his followers think he must have meant—would have exactly one field of investigation, one field in which systematically necessary illusions are in fact part of the Marxian account of reality: the dynamic by which social relations take on apparently autonomous forms of appearance such as, most famously, the fetishism of commodities, but also the “trinity formula” in the third volume of Capital (according to which it appears that capital generates interest, land generates ground rent, and labor generates wages as if by magic, thus concealing the “definite social relation of production” that links all of these phenomena). It is far from self-evident that it makes sense to describe the commodity-fetish, much less rent or wages, as an ideological form, although doing so might underscore that “the economy” itself is a contingent way of organizing human life rather than an objective baseline.

However, what genuinely links these economic forms to “ideology” in the narrow sense of “the illusory autonomy of ideas,” which is what the term always means when Marx actually employs it, is that they are all phenomena in which economic forms take on a seeming independence from material production. This happens most purely in the appearance of money that breeds more money out of itself, in a contraction of the M-C-M’ (money—commodity—more money) cycle to M-M’ (interest or financial devices that seem to create their own value). Economic forms are ideological to the extent they resemble mere ideas, but they resemble mere ideas for concrete material reasons. The commodity-fetish happens because workers are separated from the means of production, not because they have bad ideas. Hence, the cure for ideology is not to change ideas but to change social relations. And if that were to happen, the overcoming of ideology would be an insignificant side effect. All of this has little in common with either the “worldview” interpretation of ideology or with the assumption that ideology is a substantial obstacle to revolution. So, it is possible that ideology as we know it simply is not a thing.

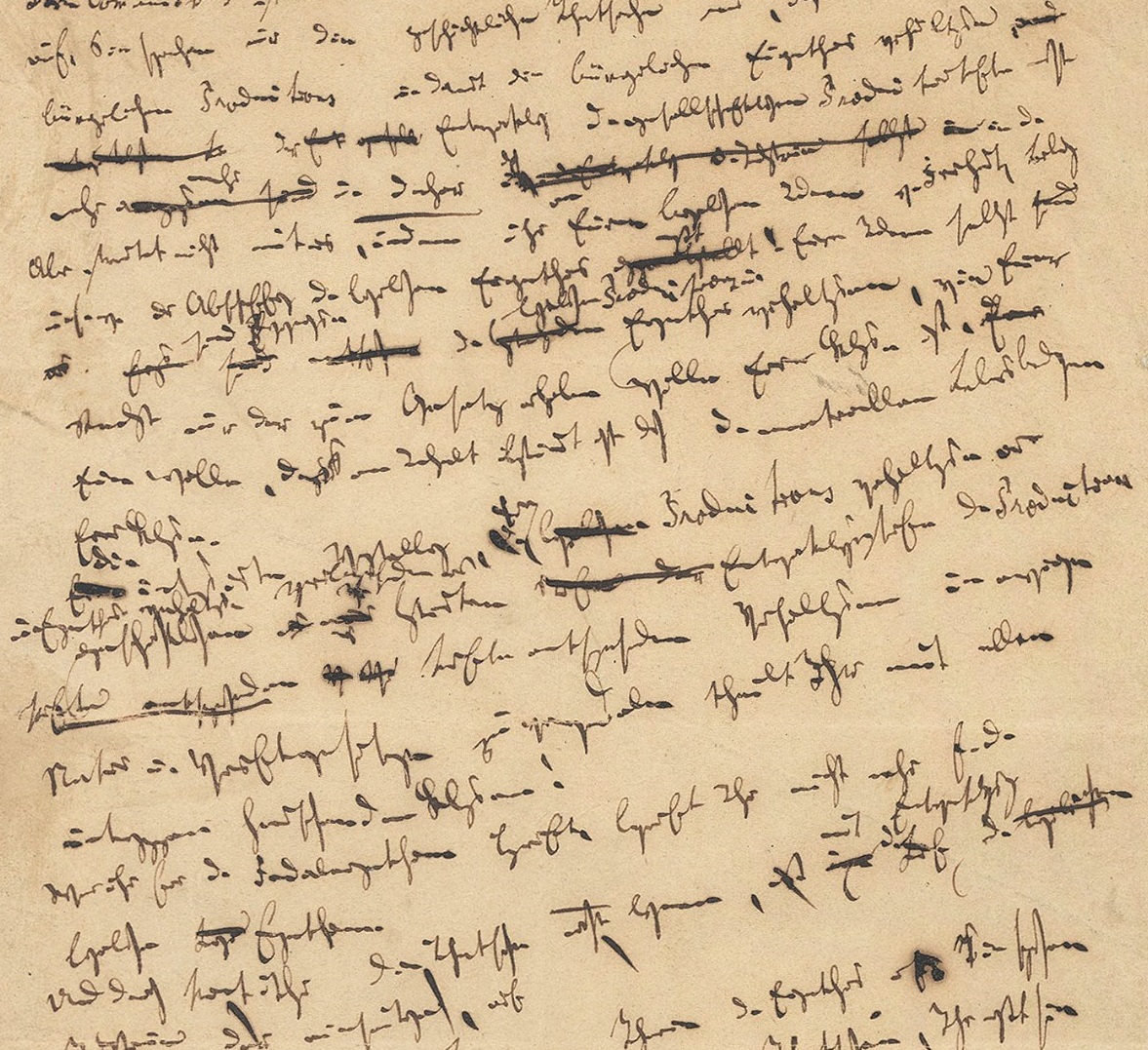

That said, it was taken to be one in the twentieth century, and that itself reified the idea. There was a time when the relevance of ideology theory to the discipline of art history appeared to be self-evident. The point is not to mourn that time’s radicalism, which was neither more nor less radical than our own. As a reference against which to compare things as they are now, though, consider the following attempt at defining ideology, which I quote from a paper that T.J. Clark delivered to a session on “Marxism and Art History” at the 1976 meeting of the College Art Association:

I.

Can we agree on the following working definition of ideology? (Probably not, but let’s proceed.) Ideologies are those systems of beliefs, images, values and techniques of representation by which particular social classes, in conflict with each other, attempt to ‘naturalise’ their own special place in history. Every ideology tries to give a quality of inevitability to what is in fact a quite specific and disputable relation to the means of production—it pictures the present as ‘natural’, coherent, eternal. It takes as its material the real substance, the constraints and contradictions, of a given historical situation—it is bound to refer to them somehow or other, bound to use them, otherwise what content would it have, what (distorted) information would it convey, what would it be for? But it generalises the repressions, it imagines the contradictions solved.

II.

So part of the task of a Marxist art history ought to be to reveal the work of art as ideology.

You mean to say:

Look! This work of art is ideological!

No, not exactly. I mean to say:

Look! This work of art is ideological, and to say that—to see that—is to see it differently, to see it more completely. See it as a real object, produced by real people in real historical circumstances, produced to do a certain job, to validate a particular order of things; or sometimes, more interestingly, produced to paper over the cracks between two different orders, two liturgies, two concepts of nobility, two classes, two ideologies.

See it as a real object, meaning, secondly, see it: get a grasp of its order, and the particular job this order, this arrangement of things had to do.[18]

Ideological artifacts are complex and vital things, then. Seeing how artworks are ideological—to “see” them properly at all, as the mantra-like repetition of the word insinuates—is important for understanding or even perceiving that complexity. A corollary, as Clark makes clear over the next few pages of his talk, is that good art history and good ideology critique are all-but synonymous, and by extension:

that there need not be a contradiction between art-historical work and work on—against—art history as it exists, in real terms, in the form of institutions like graduate school, the board of Art Bulletin, Civilization, the CAA.

They ought to be part and parcel of each other. And the balance between them will be constantly changing, according to an analysis of possibilities, necessities. The better the ‘art history’ they produce, the more unavoidable will be the moves against the establishment—the less easy it will be to shrug them off as ‘militancy’ or ‘Marxism.’ The more we can expose the vacuity of art history’s highest, most trumpeted achievement—its much vaunted ‘contact with the object,’ its spermatorrhoeic love-affair with ‘creativity’ and ‘genius’—the easier the institutional struggle will be.[19]

For “contact with the object,” one can mentally substitute more recent methodologies. Clark’s faith in “the institutional struggle” is the keynote here. Attention to ideology in art is the battering ram that breaks down ideology in art history, by sheer force of doing a better job of it (though he warns that “even [ideology], remember, is a concept which could be recuperated, on its own”).[20] Several years later, Clark would write the following, with a different emphasis:

The sign of an ideology is a kind of inertness in discourse: a fixed pattern of imagery and belief, a syntax which seems obligatory, a set of permitted modes of seeing and saying; each with its own structure of closure and disclosure, its own horizons, its own way of providing certain perceptions and rendering others unthinkable, aberrant, or extreme.[21]

It is against such “inertness” that a properly sensitive ideology-critical art history would stake a claim for superiority on not just political but also scholarly grounds. The proof is in the pudding. While this still seems like a viable research program, it may be that the material itself, the stuff of ideology, is no longer so interesting and contradictory as Clark makes it sound.

This would be a possible reading of the first article in the present issue of Selva: a major, previously untranslated essay by Theodor Adorno that was first published in German in 1954. Adorno’s “Contribution to the Theory of Ideology” is a hybrid creature. It is, on one level, a straightforward account of the vicissitudes of the term “ideology” from its invention by Destutt de Tracy in the late eighteenth century to its uptake in mainstream sociology in the years after World War II, with pitstops along the way for discussion of Karl Mannheim, Vilfredo Pareto, and Max Scheler. The essay’s polemical edge emerges in Adorno’s attack on the identification of ideology theory with a “sociology of knowledge.” This positivist approach makes a hash of the dialectical enmeshment of “socially necessary illusions” (as Adorno puts it in other, related writings)[22] with their truth-content, since every ideological form bears the mark not only of the injustice that makes it necessary, of the Verblendungszusammenhang or “context of delusion” that it cannot escape, but also of the reconciliation that it projects even if only in the negative.

Adorno’s text concludes with remarks on the “concrete contemporary form of ideology” that take a somewhat different tack. Totalitarian regimes have little need for subtle misdirection. Neither, in a different though related way, does the total immanence of the culture industry, the motto of which, as Adorno observes, is the absurd command to “become what you are.”[23] At this point, ideology is nothing but the statement that the world is as it is: “Nothing remains of ideology other than the acceptance of the status quo itself, as a model of conduct that acquiesces before the supreme power of conditions. […] [A]fter that, ideology amounts to little more than that things just are how they are, and its own untruth has been reduced to the tenuous axiom: it could not be any other way than it is.” In Adorno’s account, then, an inversion seems to have taken place in the nature and function of ideology over the first half of the twentieth century, marking a transition from the period of the bourgeoisie’s contested ascendance (Clark’s examples work best here) to the “totally administered world” of the post-fascist and, in a sense, post-bourgeois era.

Instead of substituting non-reality for reality, ideology in its contemporary form is the impeccable realism that we have since come to recognize in Margaret Thatcher’s refrain that “there is no alternative.”[24] If this is the case, then ideological art has little to work with: no “two different orders, two liturgies, two concepts of nobility, two classes, two ideologies” left to reconcile. This being Adorno, however, that apparently final reconciliation is false. The statement that things are as they are requires only a demonstration that they are not to fall apart. Hence what may seem to be the unexpected optimism of the essay’s final line: “But because ideology and reality converge to such an extent—because reality becomes an ideology of itself in the absence of any other convincing ideology—it would require only a small effort of the mind to throw off the semblance that is at once both omnipotent and void.”

At the start of this issue on ideology, then, we seem to find that ideology is over—at least in its classical (bourgeois) mode. The kind of ideology critique with which Clark identified good art history in 1976 seems powerless against tautology. What exactly could a critique of discrepancies between proclaimed values and actual practice accomplish when fascism never pretends to be justified by anything except raw force? But other conclusions are possible. Following Adorno’s essay is a long commentary by its translator, Jacob Bard-Rosenberg. Rather than serving as an introduction in a traditional sense, this text offers three meditations on certain consequences of Adorno’s argument. The first section, subtitled “The Cloud of All Knowing,” traces philosophy’s perennial if vain attempts to insulate itself from the realm of interests: the target of the early Frankfurt School’s critique of philosophical autonomy. This develops into a consideration of the roots of Adorno’s “Contribution” in his prewar engagement with the sociology of Karl Mannheim, who attempted to develop a concept of “total ideology” in which, so to speak, all cats are gray. By asserting that all positions—subject and object alike—are similarly immersed in ideology, Mannheim avoided the true solution to the “riddle” of the philosophical problematic in historical action. The next section of Bard-Rosenberg’s essay, “Labors of the Heart,” observes that the habitual analogy of the “head” to capital and the “hand” to labor makes little sense and moreover elides the centrality of the “heart” to both the success and the undoing of ideology. The “heart” has two manifestations: real love, which reunites the disjecta membra of the division of labor, versus the “heart-workers” of modern society. Heart-work’s most powerful tools are technological media, but its essence is the system of manufacture itself. The final section of the essay, “Experience Against Totalitarianism,” returns to the Hegelian problem that any critique of a partial set of interests in the name of universality might turn out to conceal partial interests of its own, which in modernity have ultimately taken the shape of corporate media in the service of a monopolist class. In an increasingly reified world, art may not be able to reverse the reduction of experience to “pseudo-experiences of ideological categories,” but it can at least provide an experience of that loss of experience, thus breaking through the semblance of false reconciliation. Art might thus serve as “a fulcrum of truth upon which some benighted resistance might turn.” Far from being otiose in the world of the culture industry, then, close attention to art might carry more weight than ever.

The next two articles are the only texts in this issue that belong unambiguously to art history proper. Larne Abse Gogarty’s “Inert Universalism and the Info-optimism of Legibly Political Art” is important, among other reasons, for coining a name for a type of work that has been widely exhibited, and widely acclaimed, in the twenty-first century without ever having been isolated for a consideration of its epistemological underpinnings. “Legibly political art,” as Abse Gogarty calls it—the prime example of which in this essay is the art of Trevor Paglen—“aims to make things visible,” or, conversely, trades on the vastness and invisibility of its objects of critique for effects that are easily recognized as versions of the classical aesthetic category of the sublime. This strategy, much as it may serve admirable political goals, such as the unmasking of state violence and corporate malfeasance, nonetheless turns out to be problematic in two connected ways. First, the “legibly political” gesture of revelation depends upon a model of political efficacy that claims to abandon conspiracy theory for the more intellectually respectable pursuit of “cognitive mapping.” But these two modes turn out not to be so easily separated as one might like to think, and in practice, legibly political art substitutes a proprietary investment in knowledge for materialist analysis, as if merely seeing through the veil were already a politics. Second, the aesthetic of sublime incomprehensibility, which is the necessary complement of the “quest for transparency” that animates legibly political art, projects as its contrary the figure of a rational, self-possessed liberal subject that has been profoundly racialized since its origins in the eighteenth century. As an alternative to “info-optimism,” Abse Gogarty closes with a provocative call for conspiracy as a “mode of creation which materializes in response to the violent abstractions of capital”—thus reclaiming a kind of strategic thinking that stands in ill repute with both defenders of liberal democracy as well as traditional leftist organizers, but which turns up as a guiding thread across several contributions to this issue of Selva.

“Bearing Witness? Forensic Architecture and the Evidentiary Power of Art,” by Fiona Allen and Luisa Lorenza Corna, is very much in the same spirit as Abse Gogarty’s critique of liberal aesthetics. Allen and Corna, however, focus on the juridical paradigm of contemporary practices, in this case that of the research group Forensic Architecture, which was founded by Eyal Weizman in 2010. Through a comparison with Allan Sekula, the authors argue that Forensic Architecture seek to restore the truth-value of photography by supplementing this imperfect medium with other sources of indexical evidence. In a related modality, their work similarly uses spatial modeling tools to construct virtual representations of events such as the murder of a protester in the West Bank or violence against migrants at the Spain-Morocco border, filling in the blanks left by necessarily partial recordings and witness testimony. Although intended to redress such injustices, this practice is ultimately constrained to accept the framework of the existing legal system, with its many ingrained prejudices. On the side of the gallery or the museum, in turn, the dynamic by which Forensic Architecture acts as a legal consultant while simultaneously exhibiting documents of this activity within the institutions of the art world does not seriously disturb either the autonomy of art or the normal operations of the justice system. Moreover, whatever efficacy this approach achieves is ineluctably bound within the limits of the individualistic human rights discourse that defines the legal sphere of modern capitalist democracies, thus foreclosing the horizon of collective (and thus potentially revolutionary) action. Against a forensic model oriented towards the reconstruction of the past, Allen and Corna finally offer examples of the “performance of prognostication” in the work of the artist R.I.P. Germain and the artistic/curatorial duo Languid Hands—Black British practitioners who project the brutally iterative logic of anti-Black violence into the future as a spur for preemptive action rather than retrospective evidence-gathering (which, on top of always coming too late, also usually tells us little more than what the oppressed already know).

Both of the above articles level tough criticisms at kinds of art that are, for lack of a better way to put it, usually thought to be on the good side of things. (And they are, at the level of intentions, at least.) Putting these texts immediately after Adorno is meant as a challenge to the field of contemporary art history, even or especially in its leftist versions. The next section of this issue of the journal returns us to critical theory. Sami Khatib’s article “Aesthetics of the ‘Sensuous Supra-Sensuous’” departs from Bertolt Brecht’s observation that a simple “reproduction of reality” tells us next to nothing about the social relations that define the capitalist mode of production, because those relations are abstracted and alienated. But the abstraction involved here is real, rather than merely conceptual. “Realist” art in the modern era, then, cannot accept surface appearances but instead must “construct” estranged aesthetic objects that bring these hidden relations to experience. In contrast to the liberal practices that Abse Gogarty as well as Corna and Allen discuss, however, a Marxian aesthetic does not stop at positivist unveiling of the real beneath its illusory forms of appearance. This is because those forms of appearance are real in their own right: as I have noted earlier in this introduction, economic forms have objective validity inasmuch as certain aspects of reality have become abstract and seemingly divorced from material production. Khatib accordingly argues that Marx’s Capital itself constitutes an aesthetic theory of the “sensuous supra-sensuous” essence of capitalist social forms that goes far beyond the traditional “visual metaphor of theory” (the very name of which is derived from the Greek verb theorein, meaning to look at, contemplate, or seize with the gaze). After Marx, Walter Benjamin was the next great exegete of this inverted world, and it is hence with the fragments of Benjamin’s “allegorical reinterpretation of the Marxian commodity form” that Khatib spends much of his essay.

Tom Bunyard’s essay “Spectacle and Strategy: On the Development of Debord’s Theoretical Work from The Society of the Spectacle to Comments on the Society of the Spectacle” marks a pivot in this issue from ideology and aesthetics to the question of strategy. As is well known, Guy Debord published The Society of the Spectacle in 1967, just in time to exert an influence on the events of May 1968. As is much less well known, Debord returned to his most acclaimed work in a dyspeptic book of Comments published in 1988. Though often dismissed as the work of a terminally pessimistic crank, Bunyard argues that Comments on the Society of the Spectacle represents a serious attempt to update the theses of the earlier text for a new era, in particular through the development of an idiosyncratic (and at first glance, apparently quite un-Marxist) theory of strategy. As Bunyard reads Debord, the essence of the spectacle is its foreclosure of collective historical agency. Capitalism expropriates history from its makers and turns it into an image to contemplate, making self-determination not only impossible but also unimaginable for its subjects. The point of revolutionary strategy is to take back control over time. While recognizing the increasingly daunting barriers in the way of accomplishing that goal, Debord’s Comments “is not an expression of failure, but rather a coolly dispassionate exposition of a difficult situation that could, perhaps, be turned.”

Jackie Wang’s contribution demonstrates the force of an elective political affinity across apparently incommensurable difference, while still remaining in Debord’s France. “The Global Circulation of a Black Radical Icon: George Jackson, the French Intelligentsia, and the Outlaw Class” largely focuses on Jean Genet’s engagement with Black radicalism. In 1970, the Black Panther Party invited the writer and ex-thief to embark on a solidarity tour of the United States. Genet was particularly taken with George Jackson, whose book Soledad Brother—a collection of letters from prison—he was responsible for having published in French translation. Jackson’s thoughts on the “prisoner class” resonated with Genet’s own first-hand experience of incarceration. Although in retrospect Genet’s identification with the Black American underclass is certainly uncomfortable (“I am a black whose skin happens to be white”), Wang argues that the more fruitful lesson of this episode concerns the global circulation of Black radicalism as a model for internationalist solidarity. This circulation of political intensities relied upon affective or even libidinal projection, to be sure, but not only that: as Wang notes, “Genet and Jackson’s outlaw identity is based on a material analysis of the outlaw’s relationship to capital,” which cannot be other than antagonistic. This transnational outlaw identity offered a line of flight out of the ruse of ideological interpellation (to adopt Althusser’s terminology). My use of the Deleuzian term “line of flight” is deliberate. As Wang also shows, Gilles Deleuze explicitly borrowed this idea from a passage in Genet’s French edition of Soledad Brother. By concluding with a discussion of the French Groupe d’Information sur les Prisons (GIP), with which both Deleuze and Michel Foucault were involved, Wang suggests a link from this earlier moment of anti-prison militancy to the contemporary abolitionist imagination.

Our last article moves from the relatively recent past to distant and partly mythical (pre)history, which turns out not to be so distant at all. It can at least be argued that all ideology is state ideology, because the state is, simply, that which calls upon us to become subjects (as Althusser notes). Genet and Jackson are powerful models for avoiding such modes of capture, but millennia of human experience suggest further ways of organizing “society against the state,” as Pierre Clastres put it. “An An-arkhé-ology, or: Preliminary Materials for Any Future Account of the State,” by Andrew Culp, is a long excerpt from a forthcoming project that attempts nothing less than to make the state unthinkable. If all state forms are founded upon an arkhé—an origin, an order, an ultimate principle—then an anarchist science can be nothing other than an an-arkhé-ology, a refusal to legitimate any state whatsoever. This science “prevents state power before it takes root.” Drawing on a heterogeneous array of sources, including Georges Dumézil’s cult book Mitra-Varuna, James C. Scott’s ethnography of Zomia (the vast ungovernable uplands of Southeast Asia), and a wide range of classicists and anthropologists, Culp develops an expansive typology of state power and ways to evade it. The bulk of the text as excerpted here consists of a series of theses and scholia on the first of several transhistorical figures of sovereign authority: the magician-ling who dominates with the captivating flash of violence. Culp’s adaptation of Deleuze’s concept of the line of flight is a connection with Jackie Wang’s text; as he notes, the magician-king’s power is “strong but blunt, which allows many codes to escape his command.” But it should be kept in mind that the magician-king is only one of the masks of the state and there will be others to contend with. If this is an an-arkhé-ology, it is also an an-aesthetics, because visibility here is not the modality of a (desirable) politics but rather a trap to avoid: “Visibility means death in the state’s war of appearances.” A more total negation of the liberal aesthetics of transparency is hard to imagine.

Finally, this issue contains Selva’s first book review: in a text that is a significant historiographic contribution in its own right, Jason E. Smith draws out some of the background of An Oblique Autobiography, a new collection of essays by the art historian Yve-Alain Bois. There will be more reviews to come in future issues.

Such is the nature of our age that any consideration of ideology seems to require a consideration of conspiracy. As I have suggested, the term need not have an entirely negative valence, and does not in the contributions that follow. A “conspiracy of equals” might yet be a good way out of hell.[25] As a prolegomenon to the articles, I would like to conclude with a brief, slanted look at conspiracy theory and its contrary, the concept of reality. A chapter in Leo Bersani’s book The Culture of Redemption, from 1990, is devoted to Gravity’s Rainbow, Thomas Pynchon’s famously paranoid novel about paranoia.[26] This chapter is a nice dialectical counterpart to Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick’s slightly later critique of “paranoid reading” (in which she cites Bersani), because it proposes an exactly opposite remedy for the same ailment: not less paranoia, but infinitely more. A normal or average paranoid reading is at pains to anticipate enemies but not to invent them. All theory is a form of pattern recognition, so this is how non-conspiratorial theory works, too: “The orders behind the visible are not necessarily—are perhaps not essentially—orders different from the visible; rather they are the visible repeated as structure.”[27] Pynchonian paranoia goes far beyond this, however—goes so far in proliferating shadowy agents and agencies, plans within plans within plans, that the narrative thread gets spectacularly lost. If ideology as Marxists often understand it (though, as I have said, there is little evidence for this understanding in Marx himself) provides an imaginary compensation for a real lack, or imaginary coherence in place of a real conflict, or a representation of an imaginary relationship to real conditions of existence, then conspiracy theory is an overcompensation or hyper-ideology.[28] Its effect is first to confirm a distinction between reality and illusion, surface and depth: “In paranoia, the primary function of the enemy is to provide a definition of the real that makes paranoia necessary.”[29] As enemies proliferate, though, any such clear distinction, not only between real and not-real, but also between self and other, starts to crumble. Slothrop (Pynchon’s protagonist) ceases to be much of a person at all as he ventures deeper and deeper into the Zone and its endlessly convoluted conspiracies.

Now, if it is the case that ideology critique, in its liberal versions (as in the cult of transparency that Abse Gogarty regrets) as well as in most leftist ones, depends on the power of unveiling truth and finding the real beneath forms of appearance, then it is hard to know how this could be squared with the Bersanian hall of mirrors. But let me return to how I began, by contrasting Bersani to Sedgwick, as hyper-paranoid versus anti-paranoid enemies of paranoia. Paranoia would seem to be the first step in any critique of ideological deception. Sedgwick begins her essay with an anecdote about a friend who refuses to put much stock in the not entirely far-fetched conspiracy theory that HIV had been created by the United States government, or more precisely, refuses to think it makes much difference whether the theory is true or not. The reparative gesture begins with the ascesis of refusing oneself the pleasure of seeing through conspiracies. Hyper-paranoia is the jouissance of indulging every imaginable conspiracy and positing the existence of further, as-yet unimaginable ones, too. If Sedgwick opposes ideology critique, then Bersani’s Pynchon would seem to be an ideology theorist to the Nth degree. But Bersani’s conspiracist ruins the logic of all ideology, whereas Sedgwick’s conspiracy-agnostic allows two contradictory ideas to coexist in peace (the US government created HIV; the US government did not create HIV), which is what T.J. Clark, among others, would call a prime function of ideology (it papers over the cracks and reconciles two orders).

To put it more strongly, it now seems that ideology and ideology critique operate in exactly the same way. Ideology is “the visible repeated as structure.” Ideology critique, or theory, is also “the visible repeated as structure.” Somewhat as in the identity between heimlich and unheimlich that Freud discovers in his essay on the uncanny, ideology and theory are secret sharers. This suggestion is a limit-case and is not meant to be taken one hundred percent seriously. In practice, we are not all hopeless or ecstatic Slothropian conduits, even if maybe we should be. We distinguish between theory and conspiracy theory and for the most part are confident in doing so because we share a world with other people who confirm such judgments—although, of course, they may just be confirming our delusions.

To banish the specter of infinite regress, let us return to an earlier stage in Bersani’s de-pathologized etiology of paranoia: “In paranoia, the primary function of the enemy is to provide a definition of the real that makes paranoia necessary.” The enemy is responsible for producing “the visible as a simulated double of the real.” Thus, the enemy who generates delusion, or the false text, is the guarantor that the Real Text exists; it has to exist insofar as it is concealed, because otherwise what would be the point of the concealment?[30] To say that someone’s consciousness is false, even one’s own, is inherently to posit the true. As the German philosopher Hans Blumenberg once tautologically but usefully put it, “Real is what is not unreal.”[31] The real is a “contrasting concept” (Kontrastbegriff), since it is never directly observable—or at any rate, any observation is subject to doubt (this is the point of the Cartesian thought-experiment). In the process of defining reality,

What is experienced and made explicit is in each case a particular unreal—that which must be unmasked, disenchanted, and debunked. In the implausibility of tradition, in the unrealities and illusions that come to vex an epoch, one can read what has become self-evident as reality and what thus remains unexpressed in it. As paradoxical as it may sound: what is experienced is not reality as reality but unreality as unreality.[32]

To return to the terminology we have been using thus far, we can say that any age, or perhaps any class or any social group or any political collective (although Blumenberg never pursues these more conflictual, indeed more Marxist possibilities) defines its reality by defining another reality as ideology. The usefulness of ideology or the propagation of false consciousness for buttressing power is well-known; the use of debunking (or, let us say, fact-checking) to the same end perhaps underappreciated. If we follow Blumenberg, who is not usually considered a radical critic of society, then the construction of a concept of reality depends largely on describing other concepts of reality as unreal, which is an exertion of social power inasmuch as some people believe in those concepts. This has perhaps been the dominant mode of liberal ideology in recent years. The content of science need not even be comprehensible so long as science is believed; we in the reality-based community know whom to trust. Again, ideology and its critique converge.

But what of the fact that things really are bad and something or someone must be to blame for it? Though hardly bedfellows, Bersani, Blumenberg, and Sedgwick converge in their suspicion of suspicion.[33] Apart from political trends being against Marxism for the past several decades, for obvious reasons, the most likely explanation for the decline of ideology theory is that, all protestations to the contrary, it has proven very difficult to use it and avoid condescendingly alleging “false consciousness” as a reason for cultural and political phenomena that one happens not to like. The circumstance that, according to traditional ideology theory, the ideologized know not what they do, or know and do it anyway, does not really sweeten the deal. So, things are bad, but blaming anyone in particular is conspiracy theory, and blaming structures, discourse, and so on is paranoid—and worse, seems to offer only counterfactuals as an alternative to things as they are. (As Adorno points out, “things as they are” are their own ideology.) A worldly opposition to the world ought to be possible. It remains to be seen whether ideology theory is always a version of the Gnostic hunch that, behind a world that is not as we would like it to be, there lurks an evil Demiurge responsible for making it so. And it remains to be seen whether a desire for the death of this world[34] is really opposed to a second overcoming of Gnosticism, as Blumenberg called it.

- [1] The most thorough work on the topic is Jan Rehmann’s book Theories of Ideology: The Powers of Alienation and Subjection (Leiden: Brill, 2013). Compare, also, the recent “Ideology Issue” of the South Atlantic Quarterly, vol. 119, no. 4 (fall 2020). Since these matters are covered at such length in these and other publications, my introduction will forgo a run-through of canonical ideology theorists (Louis Althusser, Antonio Gramsci, Terry Eagleton, Slavoj Žižek, and so on; as I will note later, though, Karl Marx himself never developed a “theory of ideology” that is recognizable in twentieth- or twenty-first-century terms). Interestingly, the post-Cold War decline of ideology theory in humanities disciplines such as art history has been accompanied by a slight but noticeable bump in work on the theme in analytic philosophy, e.g.: Amia Srinivasan, “Philosophy and Ideology,” Theoria: An International Journal for Theory, History and Foundations of Science, vol. 31, no. 3 (September 2016), 371-380.

- [2] For an earlier Marxist approach, see: Arnold Hauser, The Philosophy of Art History (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1959), 21-40.

- [3] Clark, Image of the People: Gustave Courbet and the 1848 Revolution (London: Thames & Hudson, 1973), 13.

- [4] Badiou, Handbook of Inaesthetics, trans. Alberto Toscano (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2005).

- [5] An artwork’s context may be a diasporic, hybrid, etc. community or even a multitude of communities rather than a closed ethnic, racial, or national community, as was assumed for most of art history’s existence as a discipline; cf. Éric Michaud, The Barbarian Invasions: A Genealogy of the History of Art, trans. Nicholas Huckle (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2019). For suggestions regarding a “post-culturalist” art history, compare: Whitney Davis, Hans Christian Hönes, and Jakub Stejskal, “Berlin Symposium on Post-Culturalist Art History,” Estetika: The Central European Journal of Aesthetics, vol. 54, no. 2 (2017), 238–292.

- [6] Eve Kosofsky Sedwick, “Paranoid Reading and Reparative Reading, or, You’re So Paranoid, You Probably Think This Essay is About You,” in Touching Feeling: Affect, Pedagogy, Performativity (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2003), 123-151; Bruno Latour, “Why has Critique Run Out of Steam? From Matters of Fact to Matters of Concern,” Critical Inquiry, vol. 3, no. 2 (winter 2004), 225-248. The literature on these issues is vast. It has been observed that perhaps the most lasting effect of Sedgwick’s diagnosis of paranoid reading is to have made writers very paranoid about being perceived as paranoid. That response is anticipated in her essay’s title, after all. For a recent treatment of Kosofsky’s rhetoric, compare: David Kurnick, “A Few Lies: Queer Theory and Our Method Melodramas,” ELH, vol. 87, no. 2 (summer 2020), 349-374.

- [7] Although associated with Marxism, this mode of critique is already fully developed in Hegel, as Gillian Rose has shown most persuasively: Rose, Hegel Contra Sociology (London: Athlone Press, 1981). More recently, cf. Jensen Suther, “Hegel’s Logic of Freedom: Toward a ‘Logical Constitutivism,’” The Review of Metaphysics, vol. 73, no. 4 (June 2020), 771-814.

- [8] Paul Mason does not seem to have been wrong in isolating the “graduate with no future” as a decisive factor in the insurrections that followed the 2008 financial crisis. Mason, Why It’s Kicking Off Everywhere: The New Global Revolutions (London and New York: Verso, 2012).

- [9] See, for example: Leah Dickerman, Hal Foster, David Joselit, and Carrie Lambert-Beatty, eds., “A Questionnaire on Monuments,” October 165 (summer 2018), 3-177. In the city of Madison, Wisconsin, where I happen to live, protesters in 2020 knocked down a statue of Hans Heg (an abolitionist who died fighting on the Union side in the Civil War) and threw it into a lake. Although widely reported as an instance of mob hysteria and confusion, I wonder if this action did not reveal a basically correct intuition that all statues exist on sufferance; what was the lesson of Vladimir Tatlin’s Monument to the Third International if not that this “first monument without a beard,” as Mayakovsky called it, had made all other monuments ridiculous?

- [10] It also bears mentioning that art historians are just as likely to pop up on the other side of the barricades. See, for example, David Freedberg’s Iconoclasm (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2021) and, for an intelligent critique of Freedberg’s anti-statue-smashing argument by a former student of his: Erin Thompson, “Foulest, Vilest, Obscenest,” London Review of Books, vol. 44, no. 2 (January 27, 2022).

- [11] Althusser, “Philosophy as a Revolutionary Weapon,” in Lenin and Philosophy and Other Essays, trans. Ben Brewster (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2001), 1-10 (originally published in 1968).

- [12] Night Workers, “Notes on Marxist Art History,” The Third Rail Quarterly 3 (2014), 36-39.

- [13] Disaffected Communists, “Re-emergence and Eclipse of the Proletariat” (2022), https://cryptpad.fr/file/#/2/file/ZCjeDTN67HEQi0i87Z9c9Y6W/. I should say that this essay strikes me as simplifying current dynamics between the formalized labor movement, racialized service sector work, and the broader proletariat (which includes everyone “without unmediated access to means of subsistence or means of production” rather than just the formally employed working class, as the Disaffected Communists rightly say). For a contrasting perspective on recent changes in the American labor movement, compare the work of Gabriel Winant, for example: “Who Works for the Workers?” N+1 26 (2017), https://www.nplusonemag.com/issue-26/essays/who-works-for-the-workers/.

- [14] This term was coined by Barbara and John Ehrenreich in 1977: “The Professional-Managerial Class,” Radical America, vol. 11, no. 2 (March-April 1977), 7-32. More recently it has reemerged in debates between the “class-first” wing of the American Left and its declared enemies, the partisans of “identity politics” (these probably are not labels that most people on either side would accept, but such are the battle lines that the new self-flagellating members/critics of the PMC have drawn). In recent years, class talk has reentered the art world in sometimes curious ways, as in the journal Arts of the Working Class (artsoftheworkingclass.org), the title of which almost certainly would not suggest itself to an unknowing reader based on a perusal of its content.

- [15] My understanding of these issues is greatly indebted to exchanges with John Clegg. The German Ideology is a shambles of unpublished drafts only cobbled into a book almost a century later. Following Clegg, I would maintain that some of its most famous passages have been badly misunderstood, specifically to the effect that Marx and Engels’ sarcastic appropriation of Napoleon’s pejorative use of the term “ideology” in their polemic against the early 19th century epigones of German Idealism has been persistently mistaken for a general theory of consciousness, when close attention to the text shows that their use of the word invariably refers much more narrowly to an occupational disease of intellectuals and others who are uninvolved in material production (although showing this in detail is work for another occasion). The other locus classicus is a letter that Engels wrote to Franz Mehring on July 14, 1893, in which he introduces the notorious term “false consciousness.” Like Marx in his own few uses of the word, nowhere in this letter does Engels suggests that ideology afflicts (much less dominates) the proletariat. Instead, the phenomenon he describes is a tendency to accept the “appearance of an independent history of state constitutions, of systems of law, of ideological conceptions in every separate domain”—that is, to see “spiritual” forms (in the expansive sense implied by the German word Geist) as things that exist and evolve in their own separate realm, rather than being conditioned by material production. This tendency to overvalue ideas and “superstructural” institutions is naturally characteristic of people who spend their time either thinking those ideas or maintaining those institutions, not the working classes. Engels is thus in line with Marx’s habit of speaking of “ideological spheres” or “ideological professions,” rather than using ideology as a synonym either for “the worldview of an entire class” or “ideas that deceive the proletariat into acting against its own interests,” neither of which construals are found in Marx or Engels. Indeed, probably the most succinct definition of the term in either man’s work is this sentence from Engels’s Anti-Dühring: “The philosophy of reality [Wirklichkeitsphilosophie: Eugen Dühring’s name for his project], therefore, proves here again to be pure ideology, the deduction of reality not from itself but from a concept.” (Anti-Dühring, “Section X: Morality and Law. Equality.”) In Marx’s political writings, in turn, “illusions” are most characteristic of the bourgeoisie, not the proletariat. The point of the famous lines in The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte on the “self-deceptions” of the bourgeoisie (which dresses the content of its revolutions “in Roman costumes and with Roman phrases”) is, after all, to contrast these with the proletarian “revolution of the nineteenth century,” which has no need for “this conjuring up of the dead of world history.”

- [16] Vladimir Lenin, What is to be Done? Burning Questions of our Movement (New York: International Publishers, 1929), originally published in 1902. This line of thinking has a self-evident appeal for radical academics, even if not many call themselves Leninists these days.

- [17] E.g., Paul Mattick, Anti-Bolshevik Communism (White Plains: M.E. Sharpe, 1978).

- [18] T.J. Clark, “Preliminary Arguments: Work of Art and Ideology,” in Papers Presented to the Marxism and Art History Session of the College Art Association Meeting in Chicago, February 1976 (Los Angeles: Department of Art, University of California Los Angeles, 1977), 3. Underlining and British spellings in the original. For a recent treatment of this text in the context of 1970s ideology theory, see: Jeremy Spencer, “The Place of Ideology in Materialist Histories and Theories of Art,” Consecutio Rerum, vol. 10, no. 10 (2020-2021), 425-449.

- [19] Ibid., 5.

- [20] Ibid., 6.

- [21] Clark, The Painting of Modern Life: Paris in the Art of Manet and his Followers (New York: Knopf, 1984), 8.

- [22] Adorno, “On the Logic of the Social Sciences,” trans. Glyn Adey and David Frisby, in The Positivist Dispute in German Sociology (New York: Harper & Rowe, 1976), 115. Although not published until 1969, this text was drafted in the context of an argument with Karl Popper in 1961.

- [23] A slogan that has had a long afterlife. In 1995, a posthumous collection of essays by the psychedelic guru Alan Watts appeared under this title.

- [24] The most influential recent account of this situation is Mark Fisher’s book Capitalist Realism: Is there no Alternative? (Winchester: Zero Books, 2009).

- [25] During the French Revolution, Gracchus Babeuf named his proto-communist secret society the Conjuration des Égaux.

- [26] Bersani, The Culture of Redemption (Cambridge, MA, and London: Harvard University Press, 1990), 179-199.

- [27] Ibid.

- [28] The traditional models to which I allude have undergone notable transformations since the 1960s. Lacanian ideology theorists such as Slavoj Žižek tend to see sociality as coterminous with ideology, meaning that the “real” as we consciously know it is opposed to the Real as a structuring gap or absence (or to the “sublime object” that occupies this structural position): “‘Reality’ is a fantasy-construction which enables us to mask the Real of our desire … The function of ideology is not to offer us a point of escape from our reality but to offer us the social reality itself as an escape from some traumatic, real kernel.” Žižek, The Sublime Object of Ideology (London: Verso, 1989), 45. This is an inversion of traditional ideology theory because it describes the social as the result of an ideological projection structured by a traumatic gap (the social, in other words, has the shape that it does because it symptomatically “resolves” or compensates for the impossibility of desire), as opposed to identifying ideology as an imaginary reconciliation of contradictions in social reality. In short, this seems to be an inversion of Marx’s inversion of “base” and “superstructure,” an inversion of the real object/projected image inversion in the “camera obscura” model of ideology, or at least is easily confused with one: ideology here seems to project social reality and not vice versa. Practices and institutions reveal an ideological orientation to the objet petit a (etc.; there are other versions of this terminology) that structures the subject, and although the position (and thus also the material representation, e.g., the person of the sovereign in a monarchy) of that “sublime” object is determined by its structural place amidst these practices and institutions—is produced by them—it is hard to ward off the idealistic implication that the sublime object comes first, social materiality second. A possible redress for the apparently anti-Marxist if not anti-materialist implications of the Lacanian model is to square the circle by identifying the unconscious or the drives with the proletariat or with production, rather than with the superstructural sphere to which Marx consigns mental forms. The “base” then reassumes its position as the Real vis-à-vis a “reality” understood as ideological projection. So, if social existence determines consciousness, per Marx, the split in the subject saves the unconscious for the “base” given that the unconscious is, definitionally, not conscious. An extraordinarily ambitious attempt to do something of this sort can be found in Samo Tomšič’s book The Capitalist Unconscious: Marx and Lacan (London and New York: Verso, 2015), which develops a “labor theory of the unconscious.” A further consequence of the Lacanian approach (which at times seems oddly reminiscent of Mannheim’s “total ideology”) is the by now very familiar idea that the fiction of stepping out of ideology is “the very form of our enslavement to it” (Žižek, Mapping Ideology [London and New York: Verso, 1994], 6). In the main text of this introduction, I insinuate that this may be true of contemporary liberal politics. However, the advantage of expanding the concept ideology to the point that it becomes the all-pervading medium of sociality if not cognition as such remains unclear to me, even if we grant that Žižek and others in his school may be warranted in noting that Hegelian recognition or intersubjectivity is always really misrecognition.

- [29] Ibid., 189.

- [30] Clark: “[O]therwise what content would it have, what (distorted) information would it convey, what would it be for?”

- [31] Blumenberg, “Preliminary Remarks on the Concept of Reality,” trans. Hannes Bajohr, in Bajohr, Florian Fuchs, and Joe Paul Kroll, eds., History, Metaphor, Fables: A Hans Blumenberg Reader (Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 2020), 117. Emphasis in the original (as below).

- [32] “Erlebt und ausdrücklich gemacht wird das jeweils Unwirkliche, das was durchschaut, entzaubert und bloßgestellt werden soll. An der Unglaubhaftigkeit des Überlebten, an den zum Ärgernis gewordenen Unwirklichkeiten und Illusionen einer Epoche läßt sich ablesen, was ihr als Wirklichkeit schon selbstverständlich geworden ist und damit unausdrücklich bleibt. So paradox es klingen mag: nicht Wirklichkeit wird als Wirklichkeit erfahren, sondern Unwirklichkeit als Unwirklichkeit.” Blumenberg, unpublished draft manuscript cited and translated in Hannes Bajohr, History and Metaphor: Hans Blumenberg’s Theory of Language (Ph.D. dissertation, Columbia University, 2017), 178-79.

- [33] Marx is often a bête-noire for this sensibility; he is one of Paul Ricoeur’s “masters of suspicion,” after all. That said, where exactly does Marx ever do a paranoid reading? I have already pointed out that the “false consciousness” interpretation of Marx’s understanding of ideology has little textual basis, and the illusions that figure in his system are not ruses behind which stand evil manipulators, but instead objective phenomena with a full quotient of reality (although grasping how this is so requires an acceptance of the difficult idea of “real abstraction”). Hegel and his idealist followers need to be put on their head, but the Hegelian system is not a veil concealing the truth but rather a logical mental projection from real conditions of existence which can be changed through praxis (this is how Marx differs from Ludwig Feuerbach). I would be curious learn about clear examples of paranoid reading in Marx. If you find any, I can be reached at dmspaulding@wisc.edu.

- [34] Andrew Culp, Dark Deleuze (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2016).