Modernist Pedagogies in Allan Kaprow’s 18 Happenings in 6 Parts

Clement Greenberg famously held that modern art should itself be seen as a form of art criticism. First developed in “Towards a Newer Laocoon” (1940), Greenberg restates this position with programmatic clarity in his radio lecture “Modernist Painting” (1960), in which he argues that good modernist paintings work to define the medium of painting in rational terms and, in this way, might be seen to enact a standard of judgment.[1]At the same time, Greenberg insists on a fundamental distinction between his art criticism and that of modernist paintings: their critique is non-discursive and unconsciously produced.[2] For Greenberg, painting as criticism was an immanent practice—it was enacted through the medium of painting, rather than verbal argument. He writes: “self-criticism in Modernist art… has been altogether a question of practice, immanent to practice, and never a topic of theory… No artist was, or yet is, aware of it, nor could any artist work freely in awareness of it.”[3]

Prominent figures of the neo-avant-garde that emerged around 1960 generally maintained the Greenbergian idea of art as a form of self-criticism. But these artists largely rejected the demand that such criticism be carried out “spontaneously” (as Greenberg put it) and non-discursively. Conceptual artists, for instance, spent much of their time writing and publishing critical and theoretical statements about art, suggesting that art itself could simply become art criticism. In so doing, these artists broke at once with the Greenbergian principle of formalist immanence and with an approach to art practice in which one “work[s] freely” in a state of limited critical self-consciousness.

The early happenings of Allan Kaprow are not so easily understood as post-Greenbergian or postmodernist, largely because they foreground, rather than resolve, such tensions between naïve practice and critical self-consciousness, and between immanent critique and theoretical argument. To set these tensions into relief, this essay focuses on Kaprow’s 18 Happenings in 6 Parts (1959). While art historians have canonized 18 Happenings as the first happening and among the first works of US performance art, neither “the happening” nor “performance art” was a recognized medium, form, or genre at the time the work was created. Rather than making 18 Happenings intelligible through a later category, this essay describes the work as emerging from the medium of modernist art pedagogy, which itself functioned widely during the 1950s and ’60s as a dynamic mediator between the practices of art and the concepts of art criticism. Doing so invites a close, archivally based reading of the work’s many intersecting components, several of which have been neglected in favor of those that readily support the common perception of a radical break with Green-bergian modernism.[4] My aim is to show how Kaprow’s 18 Happenings engages unresolved tensions within modernist art pedagogy as it was theorized and practiced at midcentury.

As Howard Singerman has detailed, the number of American college students taking courses in studio art, art appreciation, and art history exploded during the 1950s and ’60s.[5] In this new institutional context, many instructors taught according to already established modernist pedagogical principles, ranging from Bauhaus design fundamentals to theories of pictorial dynamics and subjective expression. For Singerman, whereas the academic model of fine art education taught students to imitate nature by first copying historical masterpieces, 1950s art pedagogy confronted students with “problems” to resolve in creative, yet provisional ways. Materially, modernist art pedagogy encompassed collage and painting exercises, presentations of scientific theories of perception and experience, art historical slide lectures, and the group critique, with its injunctions towards self-reflection, social comparison, and dialog. Philosophically, modernist art pedagogy entailed a measure of ambivalence about the value of instruction for the making of art: several important teachers stated plainly that while principles of composition, perception, and communication could be taught, art itself was not teachable because it was not rationalizable or predictable.

Against this backdrop, Kaprow’s 18 Happenings foregrounded the material and philosophical ambiguities of modernist art pedagogy by placing visitors in a classroom-like environment that combined verbal instructions, painting demonstrations, and slide lectures in a structured event. Echoing the paradigmatic modernist art classroom, the often-cacophonous provocations in 18 Happenings were deeply ambivalent, refusing reduction to a specific critical position, while simultaneously eliciting acts of interpretation from visitors. By 1959, Kaprow understood his art to be this contradiction between the teachable and the unknowable, a paradoxical definition of art that resists the modern-postmodern divide.

Kaprow’s hybrid identity as an artist-critic-professor was remarkable in the late 1950s, though it was not unheard-of.[6] His own modernist teachers had similarly complex professional identities. The painter Hans Hofmann, Kaprow’s teacher in the late 1940s, lectured widely and published essays on the philosophy of art; the art historian Meyer Schapiro, Kaprow’s graduate school advisor in the early 1950s, consistently drew and painted the artworks he analyzed in essays; and John Cage, Kaprow’s teacher in the late 1950s, lectured and published critical texts of great influence. A key commonality of Hofmann, Schapiro, and Cage is that each of Kaprow’s teachers, in different ways, sought to teach students to think about and physically realize artworks that were inherently unstable, contradictory, and resistant to understanding. And they all developed their critical approaches to modern art in the classroom or lecture hall before committing their ideas to paper. Thus, with respect to the question of the ends of art criticism, the subject of this special issue, I propose that we see modernist art pedagogy as a kind of proto-art criticism. In the modernist classroom, students and teachers engaged in processes of composition, interpretation, and evaluation—processes that were simultaneously physical, intellectual, social, and affectively charged. In contrast to the tidy result of the traditional published essay, however, the pedagogical performance of critique was not only collective and pragmatic, but also open-ended and often ambivalent in its use of authority. Kaprow’s 18 Happenings was an exemplary instance of such ambivalence.

In 1959, while on summer break from teaching at Rutgers University, Kaprow took an evening class with John Cage in “Experimental Composition” at the New School for Social Research.[7] He also sublet a loft in the East Village that would shortly become the Reuben Gallery.[8] Starting in June, he began to construct an environment inside this long and narrow loft space, drawing on his recent experiments with environments at the Hofmann-inspired Hansa Gallery, which had recently shuttered. This time, though, Kaprow planned to use the environment as an organizing structure for a scored participatory performance, a significantly extended version of the short scores he had been composing for Cage’s class since 1957 and that he had used in Communication (1958), an experimental lecture he delivered at Rutgers the previous spring.[9]

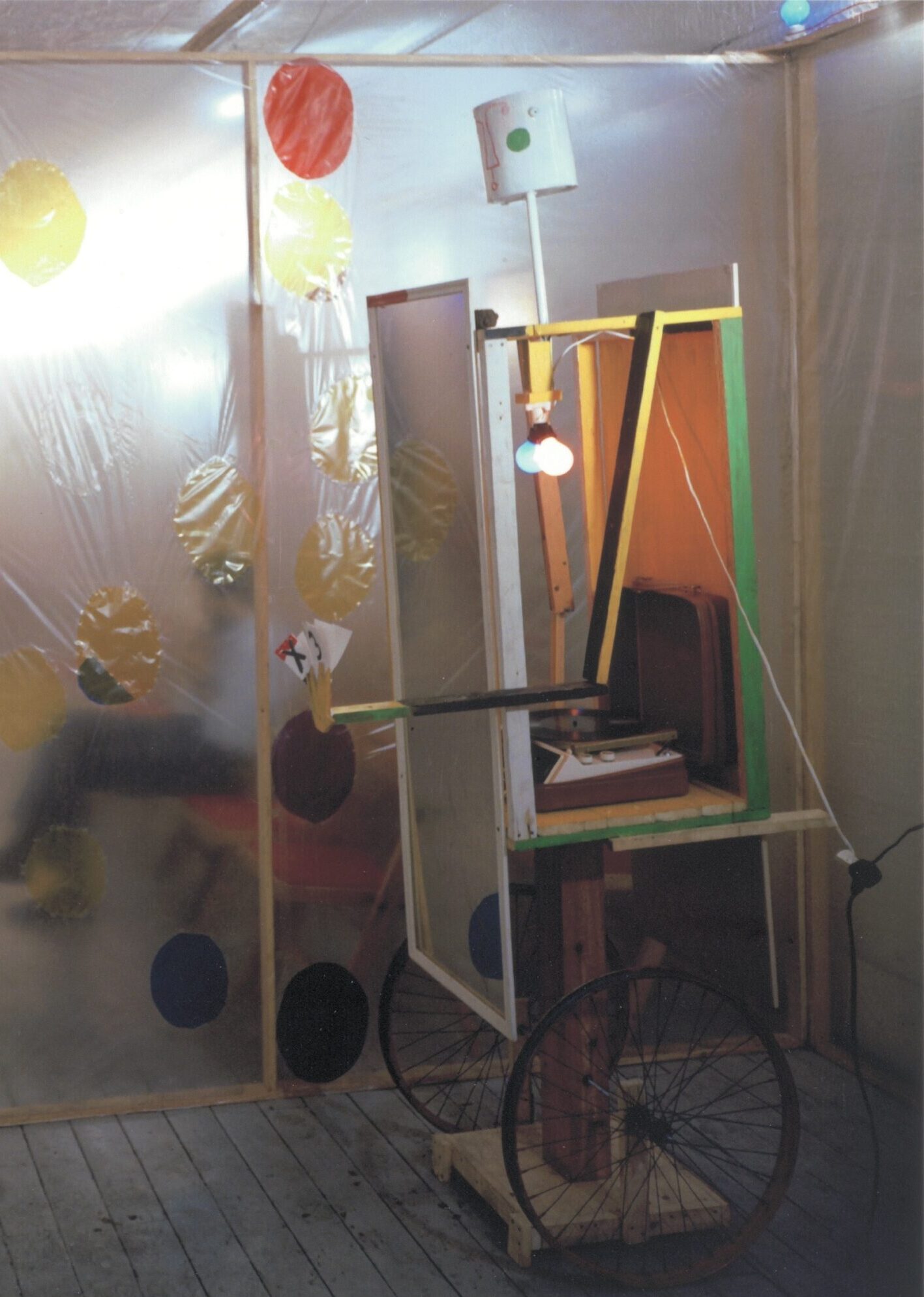

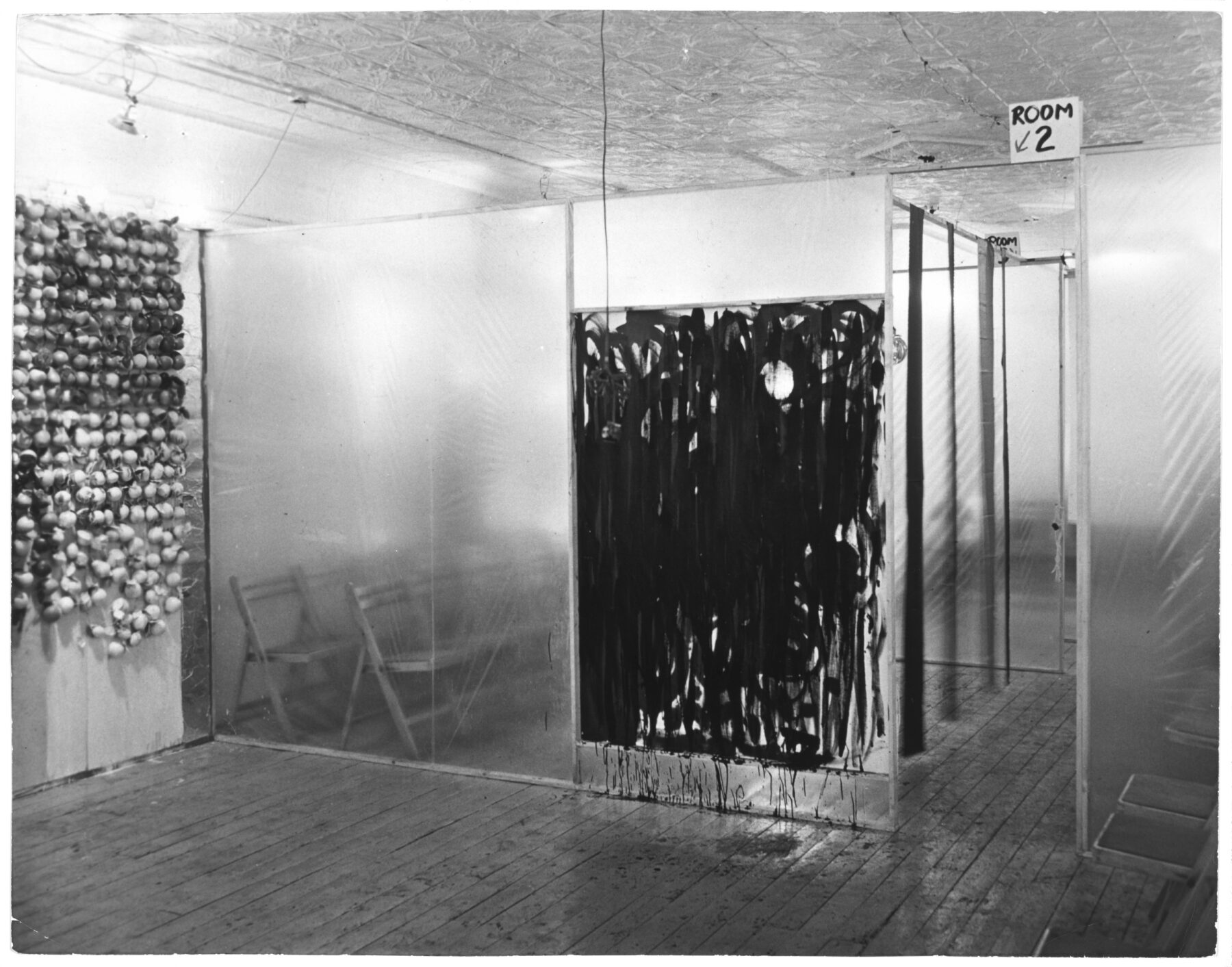

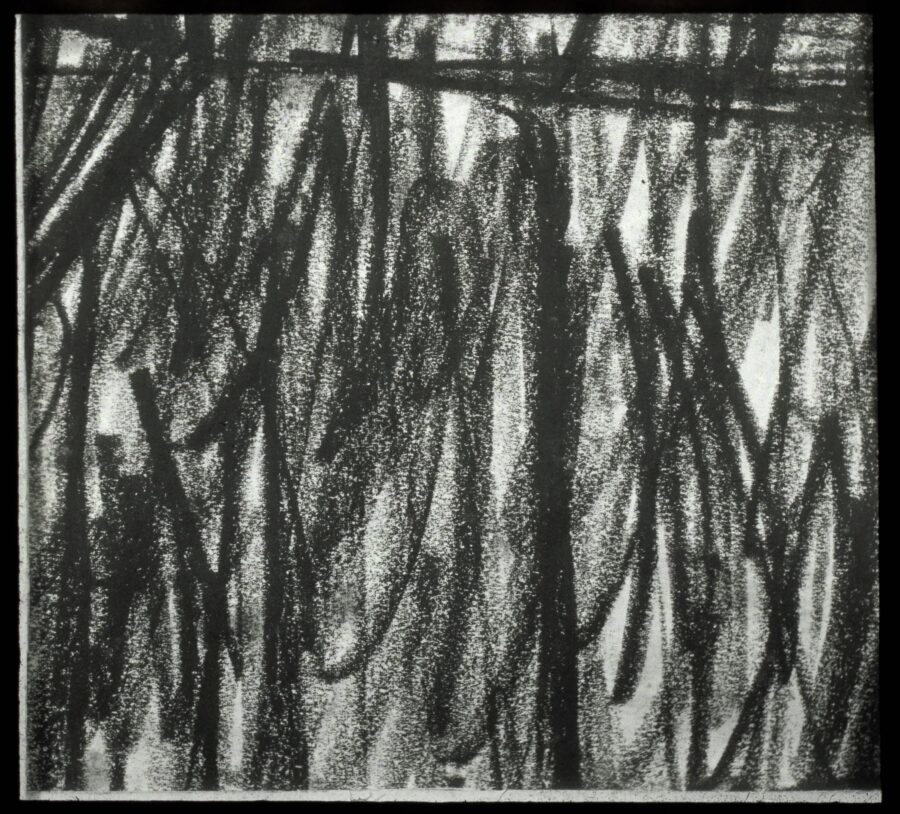

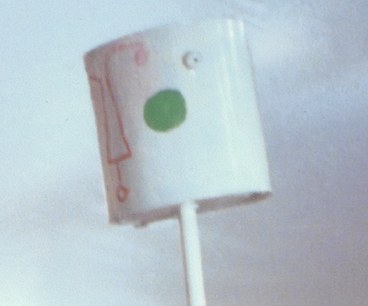

For his new loft environment, Kaprow used the cheap hardware store materials that he had been experimenting with over the previous year. He stretched plastic drop cloths over wooden frames to form translucent panels (Fig. 1). These panels served as makeshift walls to form three open rooms of different sizes, labeled “Room 1,” “Room 2,” and “Room 3.” Kaprow used some of these walls as supports for painted collages that closely resemble his paintings of the mid-1950s, such as Hysteria (1956), and painted assemblages, such as Rearrangeable Panels (1957–59). (A panel covered in wax apples and white paint from Rearrangeable Panels is visible in Fig. 2.) Colored lightbulbs and strings of holiday lights illuminated the space, which was further expanded and dynamized through the play of reflections across several full-length mirrors. Finally, Kaprow built what he called a hidden “control room” within the loft environment that contained four tape recorders connected to four speakers placed in the corners of the ceiling (Fig. 3), as well as a slide projector embedded in a painted collage panel.

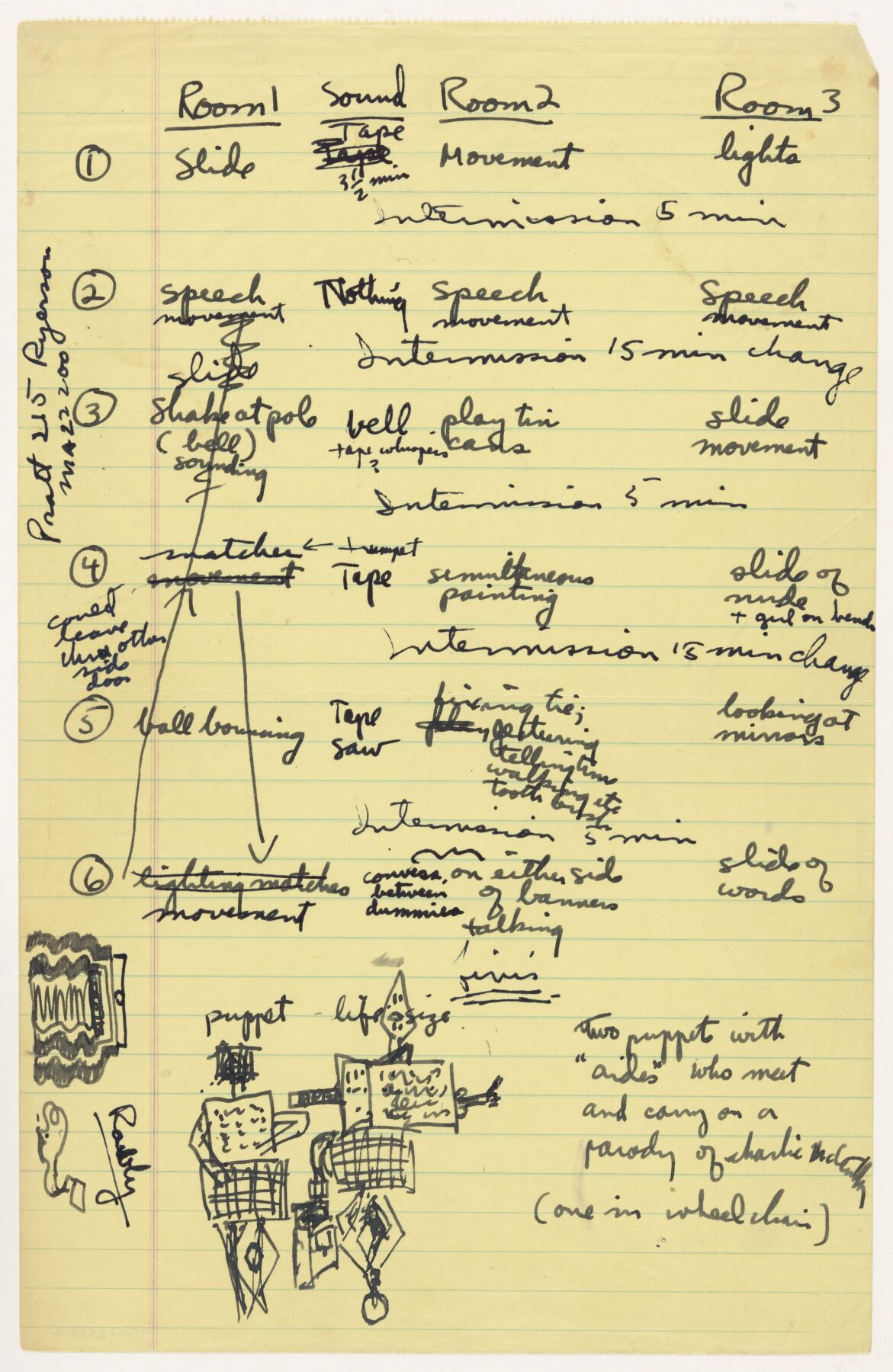

Kaprow composed a score for a performance that would take place in the environment on several evenings in early October entitled 18 Happenings in 6 Parts. [10] As indicated in Kaprow’s tables of the work, the performance consisted of six parts, with each part comprised of three simultaneous events, each of these occurring in a different room. The “18 Happenings” of the title is thus the result of a straightforward calculation: the number of parts (6) multiplied by the number of rooms (3). During the performance, a person Kaprow named the “technician” stationed in the control room played the sound collages Kaprow had made, consisting of sparse audio recordings of himself manipulating many of the same materials he used in his painted collages, such as leaves and tinfoil, as well as occasional electronic synthesizer sounds.[11]

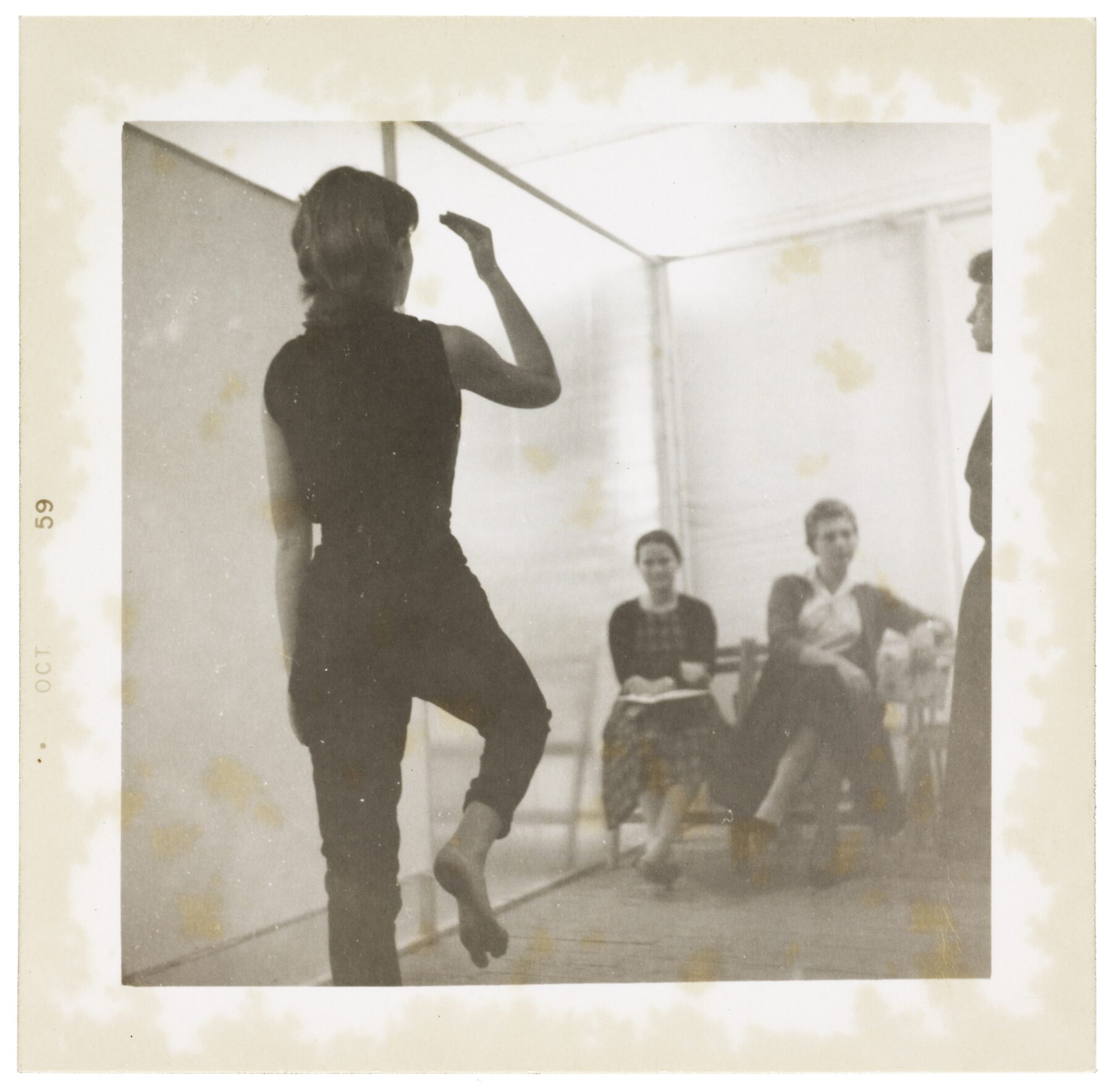

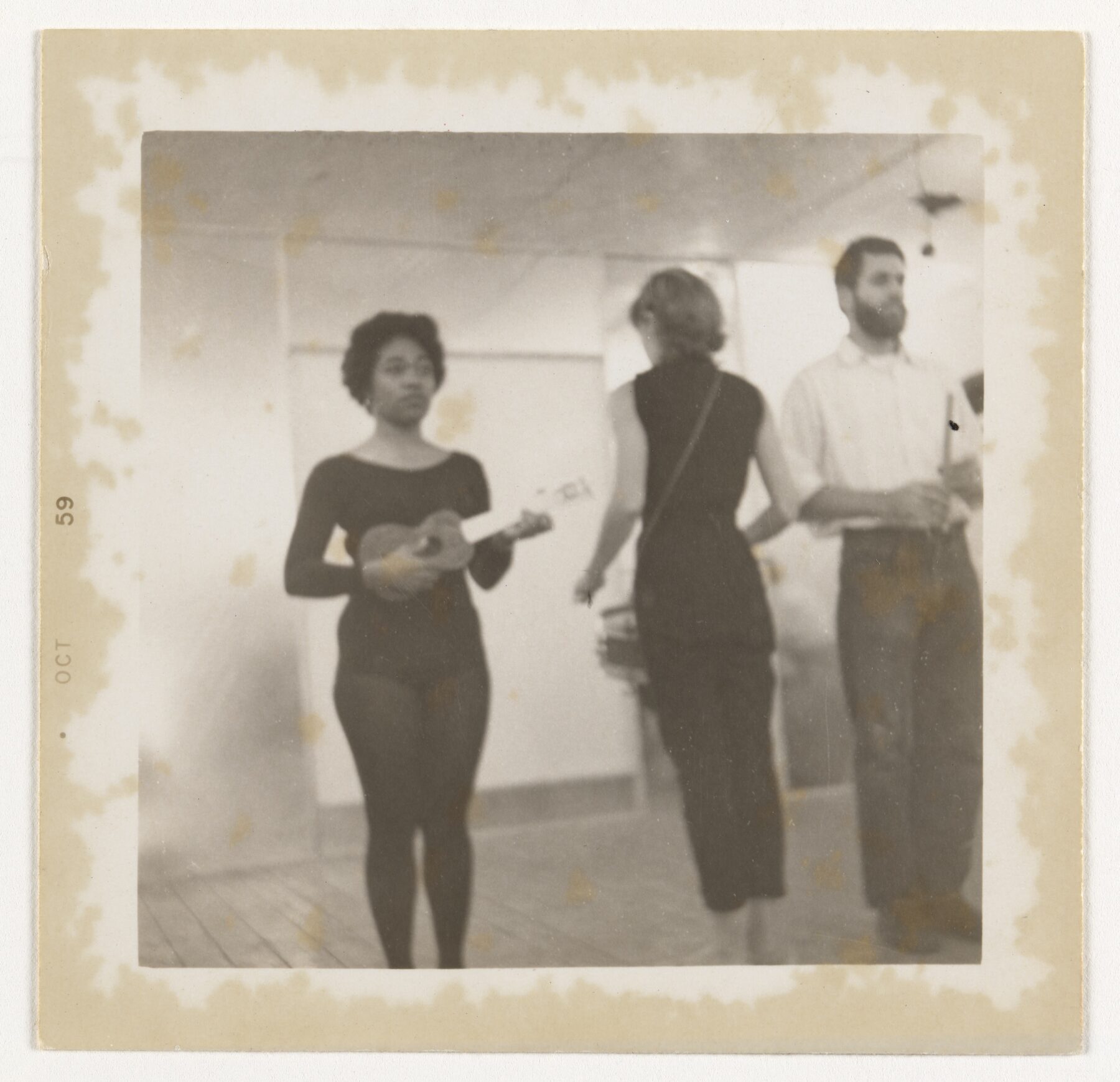

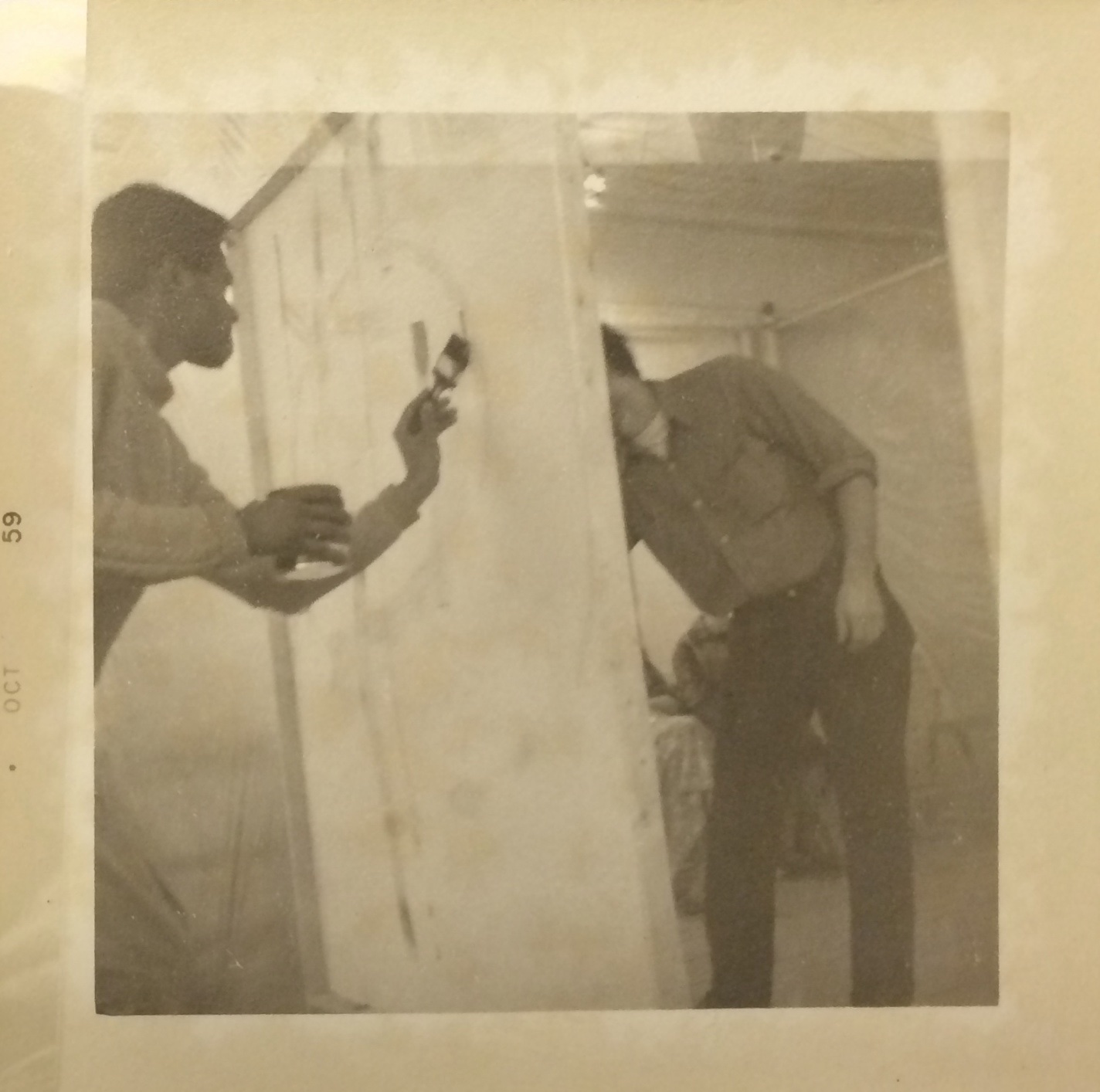

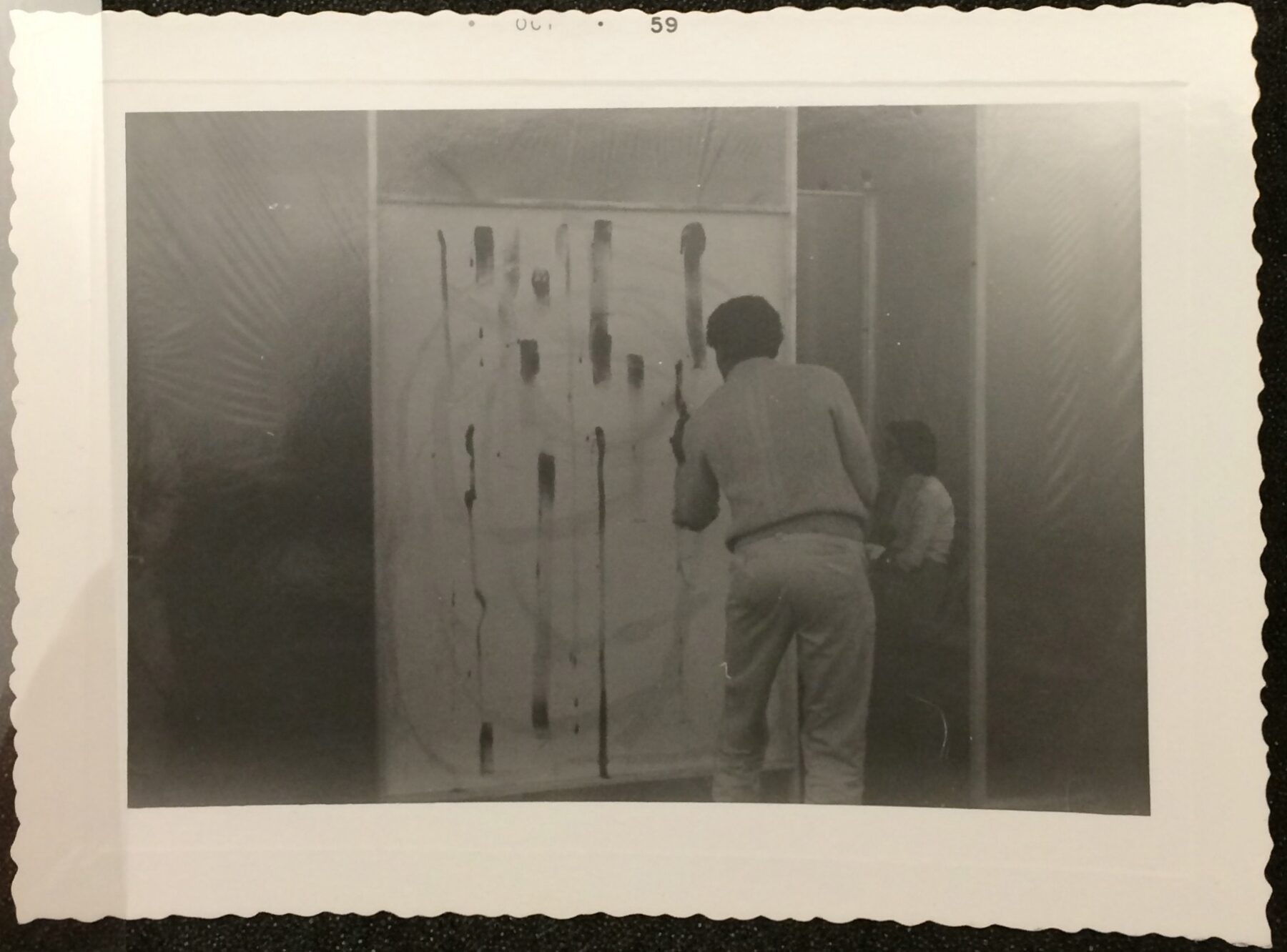

Throughout 18 Happenings, Kaprow and the other participants—his Rutgers students Lucas Samaras and Robert Whitman, Rosalyn Montague, and the modern dancer Shirley Prendergast—walked from room to room; he and his four participants executed simple gestures (Fig. 4) and mechanical tasks (such as pressing an orange juicer, bouncing a ball); operated mechanical toys and a crudely assembled figure on bicycle wheels (visible on the right in Fig. 1), and played toy-like musical instruments (a recorder, ukulele, and tom-tom) (Fig. 5.)[12] While these simple gestures and actions were in themselves easy to execute, Kaprow prescribed precise timings—sometimes down to the second, and sometimes derived from chance procedures—that made them challenging to perform accurately. In a distinct, yet simultaneous set of actions, Samaras and Whitman demonstrated modernist techniques of composition and creation, such as building a rectangular solid using oversized wooden dice (Fig. 6), while other participants painted both sides of a muslin panel (Fig. 7). Samaras and Whitman also read varied fragments of text aloud—from advertisement copy to aesthetic theory—occasionally as part of a slide lecture.

18 Happenings was participatory in a manner that was distinctly related to pedagogical practices of the 1950s.[13] The invitations, posters, and press release addressed audience members directly as “participants” and “collaborators,” while the program distributed at the start announced: “You have been given three cards. Be seated as they instruct you.”[14] A packet of index cards that each visitor received directed them to take their seat in a designated room before moving to a new room twice, upon the sound of a bell. Most visitors were instructed to visit all three rooms over the duration of the performance, and all of them would visit at least two. To signal the performance’s conclusion, a bell was rung twice. Kaprow’s imperious command to follow instructions and the jarring rings of the bell conjured up the didactic atmosphere of traditional schooling. This was something of a parody, even if Cage, who attended the happening one evening, missed the joke and later seemed to accuse Kaprow of acting like a “policeman.”[15] Nonetheless, there was free time as well; intermissions between the rings of the bell were longer than the happenings themselves, as Lepecki has pointed out, and a large portion of 18 Happenings cast visitors in informal small group discussion, as in Fig. 8, in which Meyer Schapiro and George Segal talk while others read.[16] During these intermissions, there was plenty to talk about, since, according to Kaprow’s design, one could hear everything but see only parts of the whole; as Kaprow put it in the poster advertising the work, “no matter where a person is, he [is] aware of something happening in another room.”[17] The visitors’ intermission talk was captured as part of Kaprow’s work, as it was included in its structured duration. What was refused was an easy synthesis: the pervasive and unsettling feeling of incomplete apperception among visitors’ responses could only be countered by a collective and retrospective act of reconstruction, even if, as Samuel Delany observed and Gavin Butt has argued, a complete reconstruction of the happening would remain impossible.[18]

The surface didacticism of Kaprow’s score-like instructions for visitors has obscured the more complex ways that Kaprow engaged with modernist art pedagogies throughout 18 Happenings. A key form through which Kaprow did so was the slide lecture—the primary medium of art history teaching since the founding of the field, and an emergent fixture of the visiting artist talk of the 1960s.[19] Kaprow designed Room 3 with the slide lecture in mind. He inserted a slide projector into one of the plastic walls and attached a white window shade to the opposite wall to serve as a makeshift projection screen.[20] At various intervals throughout the happening, a participant pulled down the window shade, turned off the lights, and stood by, possibly wielding a pointer, while a slide carousel cycled through roughly fifty slides. At other moments, Kaprow, Samaras, and Whitman delivered short lectures that included theoretical reflections on “art” and “time.”

Like Cage’s own performance-lectures of the 1950s and ’60s, the lectures Kaprow wrote for 18 Happenings mixed seemingly authoritative statements with playful, self-deprecating gestures to ambiguous effect. But unlike Cage, Kaprow’s lectures deliberately engaged social biases of the period. Kaprow exploited the socially constructed authority of “the lecturer” by adhering to the role’s period norms of gender and race. The lectures in 18 Happenings were all read by white men wearing standard academic attire (button-down shirts and slacks), whereas the women participants rarely spoke and wore relatively form-fitting all-black ensembles. Prendergast, who was African American, wore a leotard, casting her to some extent as a dancer and decorative figure, as André Lepecki has argued (Fig. 5.)[21] Moreover, as Lepecki notes, while Prendergast played the ukulele, a white male performer (either Whitman or Samaras) wound up a mechanical toy featuring a racist caricature of a Black figure dancing on a drum. This would have created a mimetic simultaneity that references histories of racialized performance and minstrelsy.[22] At the same time, Kaprow arguably undermined the pedagogical authority of the lectures delivered by white men. For instance, the simultaneous sound events interfered with one another, making it likely that most of the visitors could not decipher or sustain attention to the content of the lectures.

18 Happenings evoked social questions, but, as with much of Kaprow’s subsequent work, its pedagogy stopped short of explicit social critique, more often directing participants towards moments of modernist self-reflection. At the outset of this article, I noted an unresolved tension in Greenberg’s “Modernist Art” lecture between his theory of the modernist painting as a work of “self-criticism” and “self-definition,” and his proposal that the modern artist worked in a way that was unselfconscious and spontaneous. In 18 Happenings, Kaprow recasts Greenberg’s tension into one between the pedagogical demand that the artwork be explained and taught in a clear and logical form, and the theory of art’s mysterious ineffability. One lecture in 18 Happenings, read by Samaras, begins as a parody of a Romantic or Symbolist conception of art as “the most sacred of the soul’s sanctuaries.”[23] Consistent with the thesis of art’s ineffability, Samaras claims to have trouble “finding the words” that could begin to capture the inexhaustible experience of art. Nevertheless, Samaras goes on speaking—though not about art so much as about the perils of art criticism: “those who, with facile word and mocking eye, would tear the veil away… They would have us learn the game, whose rules grasped and applied, would enable all to achieve success.”[24] Despite the exaggerated tone and parodic effect of Samaras’s lecture, one can recognize a critical gesture aimed at the Greenbergian art critic, who, while intending to unveil the underlying logic of an artwork, instead reduces it to a formula—a “game” with fixed rules and largely predictable outcomes.[25] As was often the case in Kaprow’s subsequent work, this tension was mirrored in Kaprow’s choice of materials. The translucent walls of 18 Happenings enacted this tension, as they veiled and unveiled the scheduled happenings in equal measure, while, in a discursive register, the first lecture delivered in 18 Happenings made the question of the artwork’s veil explicit.

We can further grasp the unresolved tensions of modernist art pedagogy in 18 Happenings by considering a pair of art assignments included within the happening itself that appear to transform the pedagogy of abstract composition into a simple game. In Room 2, during the very next set (2), Samaras and Whitman sat down at a table in front of 20 painted blocks. Photographs show two different sets of blocks—those painted white with red numbers (Fig. 6)and another set with looser gestural marks.[26] As Kaprow explains this assignment in the score: “There are 20 blocks, the record gives 26 directions. Finish as ordered, a move at a time.”[27] The “record” here refers to an LP that Kaprow had made of his own voice and that played on a phonograph placed on the floor beside Samaras and Whitman. Another note in the same score indicates that, by the end of the allotted time, “both players should have built a cubic platform in the middle of the table.”[28] The photographs confirm that Samaras and Whitman “grasped and applied” Kaprow’s rules for abstract composition and thus achieved a kind of surefire “success” (to quote the prior lecture on art) in the form of a rectangular solid.

As a game, this assignment might initially appear somewhat boring to both execute and watch since the outcome was utterly predictable. And yet, the instructions that Kaprow read aloud on the record that played in Room 2 do not actually dictate directions. Instead, what visitors heard was something like sports commentary announced on the radio—a present-tense description of the players’ deliberations and sometimes unpredictable choices. To be sure, Kaprow’s recorded description of the composition game departs from sports commentary, most obviously because Kaprow’s commentary was recorded in advance. Nevertheless, it foregrounds the complexity and paradox of how time works in 18 Happenings, which consists of as many recorded images and sounds as live ones. Kaprow’s recorded speech begins: “Are the players gentlemen ready? … They shall ready themselves… we shall begin… the time is near… Now is the time…” Throughout this commentary with its many long ellipses, Kaprow refrains from prescribing or describing any particular move, and instead evokes an alternating rhythm of action and reaction, made up of sudden gestures (“there!”) and moments of the players/artists “carefully looking,” and again, engaging in “careful reflection.”[29] As elliptical as Kaprow’s recorded commentary is, it can be heard to enact a more ambiguous, but also more dramatic, version of Kaprow’s description of Pollock’s process of painting in his celebrated 1958 essay for Art News, “The Legacy of Jackson Pollock.” In this essay, Kaprow complicates his claim that Pollock’s “slashing, squeezing, daubing” amounted to a spontaneous “diaristic gesture,” adding that “Pollock, interrupting his work, would judge his ‘acts’ very shrewdly and carefully for long periods before going into another ‘act.’”[30] The quotes Kaprow placed around the term “act” in this passage confirms the self-distancing he built into his art assignments for 18 Happenings.[31]

A second art assignment performed within 18 Happenings that transforms abstract composition into a game redefines the game as a dialectical form that evades both solipsism and a wholly predictable outcome. This is a two-person painting assignment that Kaprow had already tried in Communication (1958). In 18 Happenings, he extends the assignmentto a full fifteen minutes, making it the longest continuous part within the happening apart from the intermissions. To set up the assignment, Kaprow inserted a muslin panel inside the plastic wall between Rooms 1 and 2.[32] Two performers then opened two cans of enamel paint on the floor next to the muslin panel, the strong odor of which immediately permeated the entire loft space.[33] One artist in Room 1 and another in Room 2 got up from their chairs and started to paint on either side of the muslin with brushes placed next to the cans of housepaint (Fig. 7). These artists were not part of the regular cast of participants, but rather conscripted from the ranks of Kaprow’s painter friends. (In the program, Kaprow named “Sam Francis, Red Grooms, Lester Johnson, Alfred Leslie, Jay Milder, George Segal, Robert Thompson – each of whom paints.”)[34]

The two cans contained paint of contrasting colors—Kirby recalls red and blue on one evening and red and green on another, while Kaprow names yellow and blue.[35] For this “simultaneous painting” exercise, he instructed the participants to paint contrasting linear forms: one artist painted “verticals” while the other painted “swirls.”[36] Although the photographs we have of this part of the happening are black and white, they vividly confirm that the painted forms bled through the absorbent muslin to create a unified composition by the end of 18 Happenings; in Kaprow’s words, they “blend” (Fig. 9).[37] The rules of this two-person painting exercise were fairly strict for a modernist assignment; as a formalist exercise, it could be seen to demonstrate the most elementary rules of color mixing. At the same time, the use of rules echoed the instruction-based score-assignments developed by Kaprow and his colleagues in Cage’s class, given that, as Kirby notes, Kaprow’s instructions were precise, even setting “the number of lines and circles” in advance.[38] Contra Cage’s negative view of improvisation, however, Kirby described Kaprow’s two-person assignment as interactive: “each [painter] responded to the work of the other and attempted to integrate it into the abstract composition.”[39] Over the several evenings of the happening, participants bent Kaprow’s rules, both in ways he considered creative and ways he considered illegitimate. Jasper Johns reportedly “used the lid of the paint can rather than the brush to make circles.”[40] There was at least one instance of outright non-compliance, as Kirby notes that “Kaprow got angry when Al Leslie wrote four-letter words instead of what he had been asked to do.” [41]

Like Greenberg’s theory of modernist art, Cage’s approach to composition in 1959 combined a rigorous philosophical logic with an aversion towards predictable results and formulas. Cage was especially concerned about what he saw as the reified forms of self-expression—even, or especially, when the artist thinks they are acting spontaneously. As Cage explained in a 1958 lecture performance (“Composition as Process”), chance procedures provided him with a way of obviating the predictable outcome of personal taste.[42] Kaprow understood Cage’s philosophical justification for the turn to chance procedures, while also retaining more dialectical approaches to compositional practice. Kaprow stated this plainly in a little-known essay he published while working on 18 Happenings that appeared in It Is. A Magazine for Abstract Art.[43] In “One Chapter From ‘The Principles of Modern Art,’” Kaprow described various methods of chance procedure and duly explained the dangers of “the ‘unmethodical’ method,” whereby “the artist just begins to imagine things, writing down his parts as he goes along until he decides to stop.”[44] Following Cage, Kaprow notes that this method of composition “is probably the most dangerous,” because “the risk is great that one… falls into the trap of coming up constantly with clichés or habits.”[45] Yet at the same time, in 18 Happenings, Kaprow reveals his preference for the “unmethodical.” As noted above, while 18 Happenings incorporates chance procedures, it also develops an alternative method for mitigating against the clichés of personal taste: collaboration, in which one person’s cliché or habit can be interrupted by another’s. If Cage’s aversion to improvisation asked performers to find a disciplined way to co-exist impersonally with another performer’s chance-derived action, Kaprow, by contrast, accepted the social dimensions of this interaction as a productive aspect of modernist pedagogy in practice, as in the group critique, as well as a source of critical self-reflection. This is an important insight of Kaprow’s, one that came to determine the future directions of happenings as well as his approach to pedagogical practice.

As a work of self-criticism, 18 Happenings reflected on its own place within art history and even went so far as to construct a tradition of art in which it might be seen to take place. In doing so, the work is, again, surprisingly congruent with at least some elements of Greenberg’s argument in “Modernist Painting,” particularly when Greenberg writes that “I cannot insist enough that Modernism has never meant, and does not mean now, anything like a break with the past. It may mean a devolution, an unraveling, of tradition, but it also means its further evolution.”[46] But it was Meyer Schapiro, Kaprow’s M.A. advisor, who even more powerfully shaped Kaprow’s understanding of modernism as a historical project.[47] Schapiro’s theory of modernism was dialectical: he defined modern art in both formal and social terms, and his language of form was related to, but also distinct from an abstract vocabulary. Schapiro first introduced a key term for his thinking about form in both medieval and modern art—“discoordination”—in his 1939 essay on the Romanesque abbey church of Souillac, and as other scholars have suggested, it effectively encapsulates Schapiro’s dialectical style as an art historian.[48] A discoordinated composition sets up, or “implies,” correspondences between “parts, relations, or properties” and then actively “negates” them. Upon closer and longer inspection, the first negation conceals or distracts from a whole set of subtler correspondences within the composition.

Schapiro demonstrated the concept of discoordination through a practice of making and showing what he called “trick slides” as part of his lectures.[49] He would take a regular slide of an artwork and flip it the wrong way around or mask out a small area with painter’s tape and project the result after or alongside the original.[50] By showing what the artist didn’t do—a counterfactual image—Schapiro was able to use contrast to reveal the force of a compositional choice, and, more broadly, the contingency of the compositional act.[51] While manipulating slides was not uncommon in the 1950s, the practice had a distinct philosophical weight in Schapiro’s hands, since it was received in the discursive context of his lectures, which, as many former students have described, issued as though extemporaneously, thus in a style that seemed commensurate with the activity of modern artists. [52]

With Schapiro’s concept of discoordination and the inherent plasticity of the slide lecture in mind, we can better understand the art historical work performed by the slide shows that played in Room 3 of 18 Happenings.One group of slides that Kaprow projected in Room 3 consisted of reproductions of canonical western paintings.[53] Most art historians have interpreted this slide show in postmodernist terms, as “modernist background noise, throwaway lines in a new kind of chance-operational theater,” as Kelley put it.[54] More recently, Lepecki has suggestively remarked that we might approach the slide show as part of a critique of Western art history.[55] Since the exact group of slides Kaprow projected has been lost, it is difficult to rigorously substantiate either interpretation, but Kaprow’s notes suggest that he selected slides that resonated with each other and with the happening itself in a loose pedagogical game of veiled correspondences across time.

For instance, Kaprow’s notes indicate that he planned to project Picasso’s painting Three Dancers (1925) and Piero della Francesca’s Flagellation (c. 1448-49) (Fig. 10). They make an interesting pair in light of Kaprow’s engagements with both Picasso and Piero as a graduate student in art history in the early 1950s. Kaprow studied Picasso with Schapiro, who argued in his own slide lectures that Three Dancers exemplified the artist’s efforts in the mid-1920s to present “somatic sensations,” especially of pain, over and against the body’s outward appearance.[56] (One of Schapiro’s former students even recalls that, in a lecture, Schapiro embodied his interpretation of the poses in the painting in an impromptu performance.)[57] By contrast, we can see that Piero’s Flagellation claims to represent intense physical pain (given its subject matter), but does so via remarkably phlegmatic postures—postures that resemble Rosalind Montague’s poses in 18 Happenings (Fig. 4). We also have robust evidence that Kaprow understood Piero to shed light on his own contradictory path towards seeking a naïve mode of creativity driven by ideas and feelings rather than visual representations.[58] Finally, and most concretely, Piero’s series of receding compartments in the Flagellation may be read as mirroring the quasi-architectural structure of 18 Happenings.[59] We might even say that the “Old Master” slide thus provided a map or diagram of the environment in which the viewers sat. Thus, at a few levels, this pairing restages Schapiro’s pedagogy of modernist discoordination: what looks at first like non-relation between pictures can be seen instead as a playful inversion and fruitful conversation between images.

In another sequence of slides projected in Room 3, Kaprow analyzed his own figure drawings, dismembering them as it were into a series of extreme close-ups, which he labeled “details” (Fig. 11). The slide of his seemingly complete Reclining Nude (Fig. 12) allowed viewers to understand the slides as fragments of a larger whole. In isolating these gestural details of his own drawings, Kaprow was looking for Schapiro-inspired discoordination in which his own unconscious fantasies play out through the hand. Whether such photographic magnification produces revelations or meaningless scribble is left open for the audience to consider on their own, in a manner consonant with modernist art pedagogy. And yet,the rhythmic variation exhibited by these slides when projected one after another demonstrated the unique productivity of discoordination itself, since Kaprow masked each slide to produce different dimensions of the image.

Schapiro’s art historical lessons can be seen as well in Kaprow’s figurative assemblage that traveled along the margins of 18 Happenings (fig. 1); however crudely constructed, its very crudeness signaled and veiled the complexity of its art historical meanings.[60] Kaprow first called it a “statue on wheels” and later a “robot figure.”[61] The figure was a simple construction of wooden bars, a full-length mirror, flatly painted primary and secondary colors, and bare lightbulbs. Inside its belly was a portable phonograph, which played polka records, next to polka dots, in an elaborate pun. With its wheels stripped of tires and held upright by a large wooden pedestal, the robot would have been an awkward, if not impossible, object to move when tipped over and guided by a human performer. As others have noted, the figure is reminiscent of additional vernacular figures, namely the sandwich man and the organ grinder.[62] At the same time, through the lens of Schapiro’s art historical pedagogy, Kaprow’s robot can be seen as a clever life-size animation of a Picasso, Miró, or Klee painting. Consider the form of the face (Fig. 13). Kaprow’s nearly continuous red line, which both delineates and joins the eyes, eyebrows, nose, and mouth with remarkable economy, recalls Picasso’s painting Le Couple (1930) and Miró’s lithograph People and Dog in the Sunlight (1949), both in Kaprow’s collection of postcards for teaching and research.[63]We can also trace the robot back to its roots as a pair of life-size “puppets” in a sketch that Kaprow made early on in his project notes (Fig. 14). Kaprow’s segmentation of the robot’s body via distinct graphic patterns also recalls “synthetic” Cubist pictures, several of which Kaprow collected as postcard reproductions, even as the reference to Charlie McCarthy, then one half of a popular TV ventriloquist act, tethers it yet further to commercial culture and advertising.

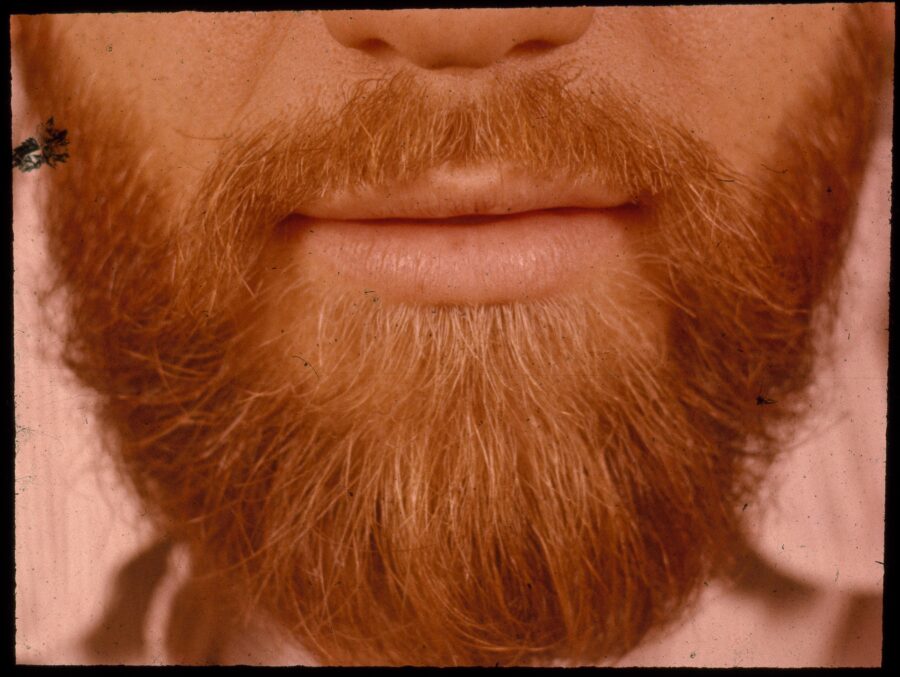

The coincidence of the sandwich man or organ grinder with the modern artist in Kaprow’s robot is deliberate. It illustrates one of Schapiro’s key insights in his social history of art, which drew provocative linkages between medieval and modern art.[64] With the rise of the marketplace in the twelfth century, and the decline of patronage by the twentieth, the artist had to sell his individual creativity and freedom on the open market. Above all, the modern artist had to participate in advertising, as Kaprow did in the slide lecture in Room 3, through his inclusion of photographs of the front and back of the Corn Flakes box and his own mouth (Fig. 15).But this did not mean that art was no longer at stake for Kaprow, or that the artist was in no way different from the common salesman. The robot was a dialectical image of the creative artist within a social and historical system. There was room to play, foregrounding Kaprow’s modernist pedagogical interest in the tension between naïve practice and critical self-consciousness.[65]

That 18 Happenings was a pedagogical work of art criticism was precisely the accusation made by Fairfield Porter in The Nation in the only published review of the happening (that was not written by Kaprow himself). In this review, Porter recognizes the formal similarities between 18 Happenings and the assemblage and performance work of Rauschenberg, Cage, and Cunningham, and alludes to its potential place in an avant-garde tradition going back to Dada and German Expressionism. However, Porter argues that 18 Happenings is fundamentally different: “Kaprow’s method is almost the opposite of most artists, literary or visual, who make things out of clichés or ordinary things or rubbish: he uses art, and he makes clichés.”[66] This is not just a claim that Kaprow’s work is derivative, as Philip Ursprung has read it.[67] For Porter, a poet and painter himself, 18 Happenings was a work of art criticism or art history masquerading as art, which, unlike true art criticism or art history, fails to illuminate its subject, and worse, “devalue[s] all art by a meaningless and deliberate surgery.”[68] Porter repeatedly emphasizes the fact that Kaprow “teaches art history at Rutgers University” and is “a teacher conscious of history.”[69] As though describing a boring lecture on modern art, Porter writes that “the voices have an unrelieved seriousness,” even though “the fragments of ideas are romanticized.”

Porter’s charge that 18 Happenings was in essence an art historically informed critique triggered an intense reaction from Kaprow himself, lending some support to Greenberg’s claim that “[no] artist [could] work freely in awareness” of their own acts of self-criticism. Kaprow was seemingly compelled to “break the usual distance between critic and artist” (in Kaprow’s interestingly ironic phrasing) by sending Porter a letter that systematically rebutted his review of 18 Happenings. In his letter he drew on his own review of 18 Happenings, which he had already published in the Village Voice under a pseudonym.[70] The letter to Porter and the published self-critique are remarkably ambivalent documents. On the one hand, Kaprow strenuously denies including more than a few “direct references to other art”—a misleading denial, as we have seen.[71] On the other hand, Kaprow describes the underlying formal design of both the environment and the performance in such detail that one is led to conclude that the happening is at least in part a theory of form itself and what Kaprow calls, in his letter to Porter, “the principles of critical practice,” namely the way in which “the very selection of facts from a context of innumerable additional facts, is a hidden value-judgment.” [72]

As noted at the outset of this essay, while today 18 Happenings is retrospectively considered a canonical work of performance art, that medium did not exist in 1959. Indeed, Kaprow insisted on this fact, writing in the press release that, “the present event is created in a medium which Mr. Kaprow finds refreshing to leave untitled.”[73] For the small circle of people familiar with Cage’s Untitled Event (1952) at Black Mountain College and his New School course, they may have recognized it as related, but Kaprow’s list of invitees suggests that many people in the audience were not experimentalists, even if they were artworld insiders, as both Thomas Crow and Ursprung emphasize.[74] It is clear that Kaprow addressed 18 Happenings to a broader audience in his poster for the event, in which he calls forth “we who sympathize with the artist’s freedom of expression and enjoy the experience inherent in advanced ideas.” [75] As Kaprow knew well, Cage rejected the theory of art as “expression.” And while I would not want to place too much weight on a single sentence, the suggestion that the happening is about “the experience inherent in advanced ideas” suggests that 18 Happenings can be read as a pedagogical work of immanent critique.

Comprised of art historical slide shows, short theoretical lectures, painting assignments, small group discussions, and various acts of unveiling, 18 Happenings in 6 Parts used the essential forms of modernist art pedagogy to enact a complex critique of modern art. Where the Greenbergian formalist critic could maintain a secure distance from and authority over the spontaneous and unselfconscious practice of painting, 18 Happenings questioned and probed this purported boundary. And by adapting pedagogy as the central medium for his work in subsequent years, Kaprow demonstrated repeatedly how theoretical statements and embodied practices could collide in ways that were productive of critical thought. Thus, rather than marking a neat historical break with modernist formalism, Kaprow’s early happenings invite us to reconsider this rich art historical moment as consisting of ambivalent attachments to and questions about the practices of modernism as they were learned and taught.

This article is adapted from Emily Ruth Capper, Happening Pedagogy: Allan Kaprow’s Experiments in Instruction, forthcoming from The University of Chicago Press in 2026. © 2026 by The University of Chicago.

- [1] Clement Greenberg, “Towards a Newer Laocoon” (1940), in Clement Greenberg: The Collected Essays and Criticism, vol. 1, ed. John O’Brian (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1986), 23–38, and “Modernist Painting” (1960), in Clement Greenberg: The Collected Essays and Criticism, vol. 4, ed. John O’Brian (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1986), 85–93.

- [2] In “Modernist Painting,” it is always works of “Modernist art” themselves, rather than modern artists, who do the valuable critical work; Greenberg laments that modern artists erroneously tend to describe their task as a search for metaphysical “purity.”

- [3] Greenberg, “Modernist Painting” (1960), 91.

- [4] There is a rich art historical literature on Kaprow’s work in which one can find varied interpretations of 18 Happenings. The major books include Jeff Kelley’s Childsplay: The Art of Allan Kaprow (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004); André Lepecki, “Redoing 18 Happenings in 6 Parts” in Allan Kaprow—18 Happenings in 6 Parts—9/10/11 November 2006 (Göttingen: Steidl Hauser & Wirth, 2007); Judith F. Rodenbeck’s Radical Prototypes: Allan Kaprow and the Invention of Happenings (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2011); Philip Ursprung’s Allan Kaprow, Robert Smithson, and the Limits to Art, trans. Fiona Elliott (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013); and Robert E. Haywood’s Allan Kaprow and Claes Oldenburg: Art, Happenings, and Cultural Politics (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2017). I will engage with these arguments as they intersect with my own on individual points, but to the extent art historians locate a critique of modernism in 18 Happenings, they tend to describe that critique as external and assured, rather than immanent, ambivalent, and pedagogical, as I do in this essay.

- [5] Howard Singerman, Art Subjects: Making Artists in the American University (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999). The material causes of this explosion of university art courses lie in the Cold War economy and postwar demographic boom, as the US government encouraged unprecedented numbers of working- and middle-class students to pursue a general college education, frequently tuition-free on the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944 (the GI Bill) or at a teacher’s college.

- [6] Kaprow’s entire artistic career unfolded while working as a professor: at Rutgers University (1953–60), Stony Brook University (1960–69), CalArts (1969–74), and University of California San Diego (1974–93). Pioneers of the artist-critic-professor role include Robert Motherwell and Ad Reinhardt, both of whom studied art history with Schapiro, taught college courses on modern art and aesthetics, and published essays on these topics. Reinhardt theorized this new “artist-professor” figure in “The Artist in Search of an Academy, Part II: Who Are the Artists?” College Art Journal, vol. 13, no. 4 (summer 1954), 315. Kaprow did, too, in in a lecture entitled “American Universities and the Advance-Guard Painter,” which was broadcast on Rutgers college radio in 1955. Allan Kaprow Papers, box 46, folder 5, Getty Research Institute.

- [7] No official record of enrollment at the New School in this period has survived, but several interviews have established that Kaprow took the course multiple times between 1957 and 1959. See, for example, Kaprow in Joseph Jacobs, “Crashing New York à la John Cage,” in Off Limits: Rutgers University and the Avant-Garde, 1957–63 (Rutgers: Rutgers University Press, 1999), 97.

- [8] In a letter to Schapiro, June 9, 1959, Kaprow describes his decision to sublet a loft in the East Village for four months to “work… in the place of the performance.” Meyer Schapiro Collection, box 110, folder 1, Columbia University Library; emphasis in the original. By the time Kaprow advertised 18 Happenings, Anita Reuben had established the Reuben Gallery in this space, with 18 Happenings its inaugural event. See the press release “Kaprow ‘Event’ to Open at Reuben Gallery,” n.d., Allan Kaprow Papers, box 5, folder 6a, Getty Research Institute.

- [9] Kaprow performed an untitled experimental lecture for an afternoon lecture series at Douglass College on the topic of “Communication.” Several years later, he titled this work Communication and categorized it as a happening. See Kaprow’s retrospective “Note on Communication,” n.d., Allan Kaprow Papers, box 5, folder 2, Getty Research Institute. See also: Joan Marter, interview with Allan Kaprow, December 8, 1995, in Off Limits, 134. On Communication, se my forthcoming book, Happening Pedagogy: Allan Kaprow’s Experiments in Instruction, 1948–1968 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2026), and, for a different reading, Tim Ridlen’s Intelligent Action: A History of Artistic Research, Aesthetic Experience, and Artists in Academia (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2024).

- [10] Kaprow’s “Instructions” in the program for 18 Happenings state that the performances took place on October 4 and 6–10. Allan Kaprow Papers, box 5, folder 6a, Getty Research Institute. For a more detailed and narrative description of the work by a friend of Kaprow’s who was present at one of the performances, see: Michael Kirby, “18 Happenings in 6 Parts / the production,” in Happenings: An Illustrated Anthology (New York: E. P. Dutton, 1965), 67–83. Kirby’s description has served as the primary basis for most subsequent writing on 18 Happenings. The other significant first-hand account of the happening comes from the important Black writer Samuel Delany, who was drawn to the performance by a poster he happened to see on the street. Samuel Delany, The Motion of Light in Water: Sex and Science Fiction Writing in the East Village, 1957–65 (New York: Plume, 1989), 108–119. My overview is consistent with these two eyewitness descriptions but also considers documentary photographs not accessible to either author, as well as Kaprow’s collections of scores, notes, tables, and diagrams.

- [11] Kaprow, “Technician Instructions” for 18 Happenings, Allan Kaprow Papers, box 5, folder 6, Getty Research Institute.

- [12] Prendergast studied microbiology at Columbia in the 1950s while dancing in the evenings at the New Dance Group, “one of the first integrated arts organization in New York City.” She later became a lighting designer and professor of lighting design. Kathy A. Perkins, “The Remarkable Career of Shirley Prendergast,” Theater, Design, and Technology, vol. 50, no. 3 (summer 2014), 31.

- [13] The press release began this way: “You are invited to collaborate with the artist, Mr. Allan Kaprow, in making these events take place.” Press release, “Kaprow ‘Event’ to Open at Reuben Gallery,” n.d., Allan Kaprow Papers, box 5, folder 6a, Getty Research Institute.

- [14] Kaprow, program for 18 Happenings, 1959. Allan Kaprow Papers, box 5, folder 6a, Getty Research Institute.

- [15] In 1965, Cage recalled: “[I] did not like to be told, in the Eighteen Happenings in Six Parts, to move from one room to another. Though I don’t actively engage in politics I do as an artist have some awareness of art’s political content, and it doesn’t include policemen.” John Cage with Michael Kirby and Richard Schechner, “An Interview with John Cage,” The Tulane Drama Review, vol. 10, no. 2 (winter 1965), 67. Branden Joseph begins Experimentations: John Cage in Music, Art, and Architecture (New York: Bloomsbury, 2016) with Cage’s “unexpectedly harsh criticism” (Joseph’s words) of Kaprow’s happenings in this interview. For a different reading of 18 Happenings in relation to Cage, see Rodenbeck’s Radical Prototypes, in which she argues that Kaprow’s chance-based performance instructions reduce human performers to mere objects, and in so doing comment critically on capitalist reification writ large.

- [16] Lepecki, “Redoing 18 Happenings in 6 Parts,” 45.

- [17] Front of the poster for 18 Happenings in 6 Parts, Allan Kaprow Papers, box 5, folder 6a, Getty Research Institute, in Eva Meyer-Hermann, Andrew Perchuk, and Stephanie Rosenthal, eds., Allan Kaprow: Art as Life (Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute, 2008), 120.

- [18] Delany, The Motion of Light in Water,108–19, and Gavin Butt, “Happenings in History, or, The Epistemology of the Memoir,” Oxford Art Journal 24.2 (2001): 113–26. Kirby confirms that, during one of the fifteen minute “intermissions,” some of the visitors “inquired of their friends what had been going on in the other rooms and described what they had seen” Kirby, Happenings, 78.

- [19] On the conventions of the visiting artist lecture of the 1960s, see “Professing Postmodernism,” in Singerman’s Art Subjects, 155–86. On the art historical slide lecture as a form, see: Robert S. Nelson, “The Slide Lecture, or the Work of Art ‘History’ in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” Critical Inquiry, vol. 26, no. 3 (spring 2000): 414–34.

- [20] Kaprow identifies the screen as a window shade in his project notes. Allan Kaprow Papers, box 5, folder 7, Getty Research Institute.

- [21] Kaprow’s project notes indicate that Rosalyn Montague was assigned one “speech,” but it is the least lecture-like and more akin to a literary experiment. Allan Kaprow Papers, box 5, folder 7, Getty Research Institute.

- [22] Kaprow himself referred to it as a “black (toy) sambo” in one of his charts for 18 Happenings. Kaprow, chart for 18 Happenings in 6 Parts, 1959. Allan Kaprow Papers, box 5, folder 6, Getty Research Institute. Michael Kirby, who was in the audience, described it as “the brightly colored figure of a Negro dancing on a drum; the legs jiggled and swung frantically and erratically when the toy was started.” Kirby, Happenings, 77.

- [23] Allan Kaprow, Score for 18 Happenings in 6 Parts. Allan Kaprow Papers, box 5, folder 9a, Getty Research Institute.

- [24] Ibid.

- [25] As it turns out, Kaprow later wrote a straightforward critique of a version of the modernist pedagogy of visual training along these lines in “The Creation of Art and the Creation of Art Education,” a paper delivered at Penn State University as part of the Seminar on Research and Curriculum Development, August 30-September 9, 1965. Allan Kaprow Papers, box 47, folder 3, Getty Research Institute.

- [26] Kirby describes the numerical blocks in Happenings, 76. An earlier set of blocks photographed during a rehearsal appears more loosely painted, and Kaprow initially planned to use painted tin cans.

- [27] Kaprow, Score for 18 Happenings in 6 Parts. Allan Kaprow Papers, box 5, folder 9, Getty Research Institute.

- [28] Ibid.

- [29] Ibid. Emphasis and ellipses in the original.

- [30] Kaprow, “The Legacy of Jackson Pollock,” in Jeff Kelley, ed., Allan Kaprow: Essays on the Blurring of Art and Life (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993), 4.

- [31] The quotes can also be read as acknowledgement of Harold Rosenberg’s prior essay in Art News, “The American Action Painters” (December 1952). On the complexity of Rosenberg’s theory of action, see: Christa Noel Robbins, “Harold Rosenberg and the Character of Action,” Oxford Art Journal, vol. 35, no. 2 (June 2012), 195–214.

- [32] Kirby recalls that not all the painters listed on the program participated, and that “Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns substituted for Red Grooms and Lester Johnson” on one evening. Kirby, Happenings, 81.

- [33] Kirby, Happenings, 79.

- [34] Kaprow, “Cast of Participants” in the program for 18 Happenings, Allan Kaprow Papers, box 5, folder 6a, Getty Research Institute.

- [35] Kirby, Happenings, 81. Kaprow [J.H. Livingstone, pseud.], The Village Voice, October 7, 1959, 11. Ursprung writes that this review was “penned by Kaprow and signed by a friend,” in Allan Kaprow, Robert Smithson, and the Limits to Art, 35.

- [36] Kaprow [J.H. Livingstone, pseud.], The Village Voice, October 7, 1959, 11. Kirby confirmed that “one painter made only straight lines; the other, only circles.” Kirby, Happenings, 81.

- [37] Ibid.

- [38] Kirby, Happenings, 81.

- [39] Ibid.

- [40] Ibid.

- [41] Ibid.

- [42] John Cage, “II: Indeterminacy,” in “Composition as Process,” in Silence: Lectures and Writings by John Cage (Wesleyan, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1961), 35–40. This is the second performance lecture in a series of three that Cage delivered at the Darmstadt Summer Course in Germany in September 1958.

- [43] Kaprow, “One Chapter From ‘The Principles of Modern Art,’” It Is. A Magazine for Abstract Art (Autumn 1959), 51–52. The curious title of this essay makes it sound like he was writing a textbook or treatise on modernism. This was apparently deliberate: in a later interview, Kaprow describes the article as “very formalistic, that is, how to do a happening” and uses the word “pedagogical” to describe the tone of this essay (“I thought, well, how wonderful to theorize and instruct”). Allan Kaprow, oral history interview with Moira Roth for the Archives of American Art, February 5 and 18, 1981, 33. Allan Kaprow Papers, box 53, folder 18, Getty Research Institute.

- [44] Kaprow, “One Chapter From ‘The Principles of Modern Art,’” 52.

- [45] Ibid.

- [46] Greenberg, “Modernist Painting,” 92. To be sure, Kaprow would have rejected Greenberg’s biological metaphor of “evolution”; Kaprow used the non-teleological metaphor of alchemy to describe change over time in “The Legacy of Jackson Pollock.”

- [47] Robert E. Haywood offers a concise account of Schapiro’s influence on Kaprow’s art criticism and practice in Allan Kaprow and Claes Oldenburg: Art, Happenings, and Cultural Politics (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2017). See also Haywood’s “Critique of Instrumental Labor: Meyer Schapiro’s and Allan Kaprow’s Theory of Avant-Garde Art,” in Experiments in the Everyday: Events, Objects, Documents, Judith F. Rodenbeck and Benjamin H.D. Buchloh, eds. (New York: Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Art Gallery, 2000). Alexander Nagel draws interesting, general connections between Schapiro’s scholarship on Romanesque art and Kaprow’s art criticism in Medieval Modern: Art Out of Time (New York: Thames and Hudson, 2012).

- [48] Meyer Schapiro, “The Sculptures of Souillac” (1939), reprinted in Meyer Schapiro, Romanesque Architectural Sculpture: The Charles Eliot Norton Lectures (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006). Kaprow knew this essay as he recorded the bibliographic information in his notebook on medieval art. See Thomas Crow’s chapter on Schapiro in The Intelligence of Art (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1999) and Donald B. Kuspit’s “Dialectical Reasoning in Meyer Schapiro,” Social Research, vol. 45, no. 1 (spring 1978), 93–129. See also: Risham Majeed, “Against Primitivism: Meyer Schapiro’s Early Writings on African and Romanesque Art,” Res 71–72 (spring-autumn 2019), 295–311.

- [49] Alongside a slide marked “Lion, Villa in Daphne, Antioch pavement mosaic,” there is a note that mentions “trick slides” in relation to a “Univ. Lecture” on “Hiberno-Saxon” material. Meyer Schapiro Collection, box 180, folder 1, Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University Library.

- [50] The trick slide can be seen as an extension of the slide comparison technique of showing two slides at once, a technique originally pioneered by Wölfflin.On Wöfflin as the “master of the slide lecture,” see: Frederick N. Bohrer, “Photographic Perspectives: Photography and the Institutional Formation of Art History,” in Art History and Its Institutions: Foundations of A Discipline, ed. Elizabeth Mansfield (London: Routledge, 2002), 246–60.

- [51] Kaprow recorded Schapiro’s idea of discoordination in his Romanesque Painting class, as “a new kind of design—discoordinations of compositional systems.” Kaprow, Romanesque Painting notebook, Columbia University, 1951. Allan Kaprow Papers, box 1, folder 5, Getty Research Institute.

- [52] Linda Seidel among others has remarked on “the vitality of [Schapiro’s] voice and incomparable sense of discovery and pleasure that he experienced in the process of looking.” Linda Seidel, “Introduction,” in Romanesque Architectural Sculpture: The Charles Eliot Norton Lectures (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006), xxiv. On Schapiro’s playful use of slides, see also: Thomas B. Hess, “Sketch for a Portrait of An Art Historian among Artists,” Social Research, vol. 45, no. 1 (spring 1978), 8–9.

- [53] Kirby called them “paintings of Old Masters” in Happenings, 74.

- [54] Kelley, Childsplay, 38. Rodenbeck summarizes Kaprow’s art historical references in 18 Happenings as “ironic pastiche” in Radical Prototypes, 159.

- [55] Lepecki, “Redoing 18 Happenings in 6 Parts,” 49.

- [56] Schapiro can be heard to make this point in his videotape lecture, The Unity of Picasso’s Art: A Master Lecture, VHS (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, in association with Gittelman Film Associates, 1980). The audio recording on the videotape was spliced together from talks at Brandeis University in 1967 and at the Albright Knox Art Gallery in 1973. It is likely that Kaprow knew Schapiro’s reading of this painting.

- [57] “Those who attended Schapiro’s lectures on Picasso will recall the ebullient choreography of his re-creation of that painter’s Three Dancers.” David Rosand, “Making Art History at Columbia: Meyer Schapiro and Rudolf Wittkower,” in Living Legacies at Columbia, William Theodore de Bary, Jerry Kisslinger, and Tom Mathewson, eds. (New York: Columbia University Press, 2006), 120.

- [58] Kaprow went to Europe for this first time in 1955 and wrote impassionedly to Schapiro about seeing Piero’s work in person. “The great masters have given me nerve to go ahead in a way I hardly expected. The sight of Piero, for example, immediately made me aware of what I think I have always wished to do. This isn’t easy to explain but you will recall that at one time I expressed the desire to be a naïf. This I later rejected as impossible and a posture at best. Well since I have come here my work has begun to look like that of a child of 4 or 5 years. Superficially that is. There is a difference in the point of view and I do not try to be a child. What I am trying to do, and what I think I wanted to do in the past is not paint scenes, objects, etc., but ideas, vague feelings, very personal associations of things with each other etc.” Kaprow to Schapiro, July 20, 1955, Meyer Schapiro Collection, box 110, folder 1, Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University Library.

- [59] Kaprow described Piero as an “architectural painter” in his course paper likely written for Schapiro’s class, “Piero della Francesca and Fernand Léger” (n.d.). Allan Kaprow Papers, box 2, folder 7, Getty Research Institute.

- [60] Kaprow first called the assemblage a “statue on wheels” (in his project notes) and later a “robot figure.” Kaprow [J.H. Livingstone, pseud.], The Village Voice, October 7, 1959, 11.

- [61] Ibid.

- [62] Kirby referred to the robot as a “sandwich man” in his description of 18 Happenings, presumably because Kaprow did at some point. Kirby, Happenings, 80.

- [63] The postcards can be found in Allan Kaprow Papers, box 59, folder 3, Getty Research Institute.

- [64] See: Schapiro, “On the Aesthetic Attitude in Romanesque Art” (1947), in Romanesque Art (New York: George Braziller, 1993), 1–27.

- [65] As he was making 18 Happenings, Kaprow budgeted the most money for “Advertising and mailing”—more than the cost of materials and wages for performers, for example. Kaprow, letter to Schapiro, June 20, 1959, Meyer Schapiro Collection, box 110, folder 1, Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University Library. Here, I allude to Walter Benjamin’s notion of Spiel-Raum. See: Miriam Hansen, “Room-for-Play: Benjamin’s Gamble with Cinema,” October 109 (summer 2004), 3–45.

- [66] Fairfield Porter, review of 18 Happenings in 6 Parts, in Allan Kaprow: Art as Life, 131.

- [67] Ursprung, Allan Kaprow, Robert Smithson, and the Limits to Art, 35.

- [68] Porter, review of 18 Happenings in 6 Parts, 131.

- [69] Ibid.

- [70] Kaprow [J.H. Livingstone, pseud.], The Village Voice, October 7, 1959, 11.

- [71] In his letter to Porter, Kaprow writes: “For example, out of some eleven pages of words you heard only a quotation from [T.S. Eliot’s] Burnt Norton and the title of a Klee painting… These are the only direct references to other art(or anything of note) in the entire eleven pages! Yet the reader will get the idea which you seem to wish to convey that ‘Professor Kaprow is too loaded down with culture which, incidentally, he fails to understand.’” Kaprow, draft of letter to Fairfield Porter, c. October 25, 1959, Allan Kaprow Papers, box 5, folder 12, Getty Research Institute.

- [72] Ibid.

- [73] Press Release, “Kaprow ‘Event’ to Open at Reuben Gallery,” n.d. Allan Kaprow Papers, box 5, folder 6a, Getty Research Institute.

- [74] While Cage later categorized some of his participatory performances as “theater,” he did not do so until the 1960s. See William Fetterman, John Cage’s Theatre Pieces: Notations and Performances (Amsterdam: Harwood Academic Publishers, 1996). As Thomas Crow points out, Kaprow targeted his invitations and other mailings to a cadre of well-connected art dealers, curators, critics, and artists. Crow, The Rise of the Sixties: American and European Art in the Era of Dissent (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1996), 33.

- [75] Front of poster for 18 Happenings in 6 Parts, Allan Kaprow Papers, box 5, folder 6a, Getty Research Institute.