“Our Difficult, Beautiful Subject”: Peter H. Feist’s Marxist Method

In a striking photograph, Otto Karl Werckmeister captured Peter H. Feist—widely regarded as the leading art historian of the former German Democratic Republic (GDR)—at the sculpture garden of the Georg Kolbe Museum in Berlin. Feist, dressed in a sharp blue suit, fixes his attentive gaze on the viewer, holding his camera poised at the ready (Fig. 1).1 Taken at the birthday celebration of cultural heritage expert Gabi Dolff-Bonekämper in the summer of 2002, the snapshot immortalizes the encounter of two scholars who shared a Marxist approach to art history across the German divide; while one is remembered for his contributions to leftist critical discourse, the other is mostly forgotten because of his association with cultural authoritarianism. When presented with the photograph, Werckmeister recalled Feist commenting, “This is how I would like to see myself.”

In his unpublished 1963 paper, “Einige Probleme des sozialistischen Menschenbildes in der bildenden Kunst der DDR” [On the Socialist Image of Humanity in the Visual Arts of the GDR], Feist proposed several guidelines for portraying socialist workers that are reflected in his own self-assured stance almost four decades later: “closeness to the beholder, contact with the beholder, without abandoning a certain probing, active confrontation; at the same time, [maintaining] a steady gaze, not an indifferent one that glances away or beyond.”2 Curiously encircling Feist’s head in the photo are three of Kolbe’s bronze statues: from right to left, the Annunciation (1923/24), Resurrection (1933/34), and Fountain Dancer (1922). This halo-like arrangement may not be entirely coincidental. Throughout his career, Feist had studied the history of sculpture, from the Romanesque period to the twentieth-century GDR. In his book Plastik in der DDR [Sculpture in the GDR] from 1965, he portrayed Kolbe as a classicist who eschewed overly abstract “free inventions of form” in favor of a “natural appearance,” thus paving the way for socialist realism.3 In an earlier essay, Feist described Kolbe’s Dancer (1912)—the prototype for the Fountain Dancer in the photograph—as his most successful work because it provided “an enduring and resting image of transient movement.”4 He argued that the realism of such artworks helps “aesthetically recognize, appropriate, interpret, enrich, and thus change people’s sense of reality.”5 According to Feist, the power to reshape cultural attitudes and behaviors resided as much in the artist as it did in the art historian who leveraged historical insights to meet the challenges of the present.

While he was finalizing his book Plastik in der DDR in November 1964, Feist was granted permission to travel to West Germany. There, he delivered the keynote address at a Marxist art history conference organized by Nicos Hadjinicolaou on behalf of the Student Council for Art History at the Ludwig Maximilian University (LMU) in Munich. In 1966, the lecture was published as a booklet called Principles and Methods of a Marxist Kunstwissenschaft (Fig. 2).6 As the sole programmatic treatise on the Marxist practice of art history to emerge from the GDR, it offers crucial insights into the theoretical and political complexities of art historical dialogue across the Iron Curtain.

Therefore, this special issue of Selva introduces the first English translation of Feist’s Principles and Methods.7 By exploring the rich set of intellectual and material conditions from which the text emerged, attending to its limits as well as its provocations, we aim to complicate prevailing narratives of twentieth-century Marxist art history. Pushing back against the tendency to view the GDR’s methodological legacy in isolation, this special issue also emphasizes the importance of transnational Marxist art historical discourses. As the two contributions on North Korea and Latin America make clear, Feist’s ideas can be read in dialogue not only with emerging Leftist approaches in the West but also larger global conversations on social art history and socialist cultural politics.

Despite the considerable growth of research on GDR art in recent years, the GDR’s academic contributions remain marginalized within historiographic accounts of our discipline. This neglect is a consequence of persistent biases in post-reunification German discourses, fueled by Cold War triumphalism and the large-scale replacement of East German academics.8 This radical institutional overhaul and the one-sided memory culture it promoted have been critiqued for their “colonial” underpinnings since the early 1990s.9 Consequently, most scholarship from the “other” Germany is hastily dismissed as unsophisticated or ideologically contaminated (Diktatursozialisation), neglecting the nuances, “coded” political debates, and individual acts of subversion.10 To echo the editors of a 2011 volume devoted to East German art, “the GDR is imagined habitually in terms of otherness, construed as the historical antithesis to the contemporary German, and indeed, western self.”11 GDR scholars—no matter how straightforwardly empirical or patently ideological—are virtually absent in contemporary research and teaching, and their books are sold for throwaway prices in online bookstores. With the awareness that key figures have either passed away or are in advancing years, there is a pressing need at this moment to document their voices and clarify the historical record.

To be certain, we do not wish to deny that authoritarian cultural policies, political pressures, and networks of censorship made it difficult, if not impossible, for Eastern scholars to conduct their research with freedom, nor do we intend to minimize the struggles of GDR dissidents. However, this does not mean that scholars operating under capitalism—in the past or present—are any more immune from political constraints given the contracting labor market, demands of the tenure system, and competition for resources amidst increasing austerity measures. The current wave of right-wing legislation in the US targeting the job security and academic freedom of university professors, as well as the recent deployment of militarized police forces by university administrators to violently suppress campus protests against the war in Gaza, have chillingly underscored the dangers of presuming otherwise. Such a comparison is not intended to elide the differences in academic pressures between totalitarian and democratic regimes but to signal the flaws of a binary Cold War narrative that fails to acknowledge the ideological entrenchment on both sides, and thus risks retrospectively exonerating the West’s neoliberal trajectory.

Rather than rehashing the minutiae of East Germany’s repressive political apparatus, we have chosen to take Feist’s arguments at face value and situate them within their larger global context. The goals of this special issue are twofold: to facilitate access to a foundational text of GDR art historical practice and to outline its historical and methodological context, both within East-West dialogue and wider legacies of Marxist thought. Peter H. Feist serves as an ideal starting point for this discussion due to his prolific output, extensive travel, and active participation in scholarly debates transcending the Iron Curtain. Despite its uneven legacy, Principles and Methods is by no means marginal; in many ways, it exemplifies art historical practices in the socialist world and among leftist intellectuals more broadly. Feist was one of the few GDR scholars who attempted to preserve East Germany’s academic legacy after reunification, mostly through his writings and interviews, and who remained committed to the theoretical premises of his work. Many of his other colleagues, some of whom were contacted by the editors of this issue, preferred not to revisit the past.

A New Concept of Art History

Peter Feist was one of East Germany’s most prolific art historians. He began his career at the Institute of Art History at Humboldt University as a senior assistant in 1958. By 1968, he was promoted to professor, and in 1982, he was appointed director of the Institute of Aesthetics and Art Studies at the Academy of Sciences. As a member of the SED (Socialist Unity Party) since 1954, Feist played a key role in shaping art history in the GDR. His achievements were recognized with the National Prize of the GDR in 1975 and the Fatherland Order of Merit in 1988. He continued his active scholarly career well after his retirement in 1991, authoring over 1,100 publications that spanned various topics, including German medieval art, French Impressionism, and twentieth-century sculpture. He contributed in equal measure to state-of-the-art historical research, contemporary art criticism, and popular survey books.12

Feist’s commitment to Marxist art history was indelibly shaped during his teenage years in Lutherstadt Wittenberg, where his family had relocated after the war in 1945.13 His interest in art history was first sparked by Professor Oskar Thulin’s lectures on Christian art at the Melanchthon-Gymnasium, leading to his involvement in organizing tours and exhibitions at the Luther House Museum. It was also during this time that he first became involved in leftist politics. Wrestling with his guilt over the death of his mother (a converted Jew) at Auschwitz and his own involvement in the Hitler Youth, Feist joined the Free German Youth movement, an antifascist collective dedicated to rebuilding a more democratic Germany (at least in its initial conception).14 He became an active member, participating in the group’s conferences, lectures, and debates, and eventually served as its director of city culture (Stadtkulturleiter).

In 1947, Feist commenced his undergraduate education at the Martin Luther University of Halle-Wittenberg, where he studied art history, history, and what was then called “oriental archaeology” (a now-obsolete academic field that encompassed the study of all of Africa and Asia).15 He attended courses taught by notable scholars such as Wilhelm Worringer, Franz Altheim, Hans Junecke, Heinz Ladendorf, and Heinz Mode, an inveterate communist who profoundly shaped the young scholar’s intellectual development. Reflecting on this influence, Feist recalled how Mode

strengthened my conviction… of the importance of Near Eastern art for the formation of European art, won me over to the method of elucidating the course of art history by observing the migrations and transformations of pictorial motifs, including cross-cultural ones, and above all to a Marxist understanding of history and art history.16

Under Mode and Ladendorf’s supervision, Feist completed his doctorate in 1958, writing a nine-volume (!) dissertation that explored the 5,000-year history of the beast tamer motif from the ancient Near East to Romanesque Europe.17 Adopting an explicitly Marxist approach, he emphasized the evolution of art according to specific laws or principles while also criticizing reductive interpretations of artistic phenomena as mere reflections of social and political conditions.

Six years later, when Feist received the invitation to the Munich conference, he had recently completed three short books on French Impressionism, two of which centered on Auguste Renoir and Paul Cézanne, and was in the process of finalizing his monograph on GDR sculpture. He thus stood at the cusp of his burgeoning career. Indeed, the years leading up to the release of Principles and Methods were marked by extensive travel and interactions with the international academic community that would eventually solidify his standing as one of the GDR’s leading art historians. Between the construction of the Berlin Wall in August 1961 and the end of 1966, he attended academic conferences and cultural events in both the Eastern Bloc and the West, visiting cities such as Prague, Moscow, Sofia, Florence, Rome, Bonn, Munich, Bologna, Venice, Hamburg, Trier, Aachen, London, West Berlin, Bratislava, and Münster.18 The publication of Principles and Methods in 1966 was immediately followed by a rapid series of professional advancements. That same year, he completed his habilitation and assumed the role of interim director at Humboldt University’s Institute of Art History, followed by his promotion from senior assistant to lecturer (Dozent) in 1967, then to professor in 1968, and full professor in 1969.

Even as the meteoric rise of Feist’s career unfolded, the early 1960s marked a period of profound crisis for the discipline of art history. On November 13, 1962, a collective of East German artists published an open letter in Neues Deutschland titled “Wir brauchen eine neue Konzeption der Kunstgeschichte” [We Need a New Concept of Art History], aimed at art historians, art critics, and museum and gallery employees.19 While the artists celebrated their own considerable progress in developing socialist artistic practices, they reproached art historians for their reliance on outdated bourgeois historical frameworks and inadequate understanding of socialist art and its aims. The letter argued for a new art historical approach that prioritized the perspective of the working class and closer engagement with contemporary socialist art production, concluding with a call for reforms in art historical education and research to ensure its alignment with socialist ideals.

In response, on December 20, Feist drafted a letter on behalf of the Academic Advisory Board for Art History to the State Secretariat for Higher and Technical Education.20 While it emphasized the discipline’s contributions to research, teaching, and public engagement that met the artists’ demands, it also admitted the need for further improvement to fulfill art history’s mandate to “guide the social processes of the socialist cultural revolution with scientific knowledge.” To this end, Feist proposed a comprehensive review of the research and teaching methodologies at all art history institutes, noting that this process was underway at Humboldt University.

The open letter heightened the urgency to address what were already longstanding criticisms of art history’s perceived “bourgeois” tendencies and lack of Marxist analytical rigor.21 As early as the 1950s, the Institute of Art History at Humboldt University came under particular scrutiny for its continued focus on traditional topics and neglect of historical and dialectical materialism.22 Since his appointment in 1958 as a senior assistant, Feist had been working closely with institute director Gerhard Strauss to realign its research and teaching with the GDR’s cultural-political objectives. This effort was in response to the State Secretariat’s mandate to “end the bourgeois academic understanding of art history and develop the institute into a leading center of Marxist art history.”23 Nevertheless, the concerns amplified by the open letter prompted the SED’s Central Committee to investigate the institute in April 1963 and again in early 1964, resulting in Strauss’s censure and rising concerns over the decline in student enrollment.24 With the fate of the discipline on the line, Feist and his fellow senior assistant Albrecht Dohmann began to formulate the institute’s “conception” of art history in consultation with Eberhard Bartke at the Ministry of Culture to address these criticisms.25 In an early draft, Feist asserted that the study of art history promotes socialist consciousness by expanding knowledge of art’s historical past and present, which in turn helps the advancement of contemporary artistic practices. Because this consciousness is indispensable to “the increase in labor productivity [and] the expansion of the material basis for further socialist-communist development,” he concludes that art history “indirectly supports material production.”26 While these efforts temporarily appeased the authorities, the discipline was continuedly pressured to further integrate Marxist principles into its teaching and research throughout the decade.

It is against this backdrop that Feist was invited to deliver his 1964 keynote lecture in Munich, “Meaning and Method of Marxist-Leninist Kunstwissenschaft,” which later formed the basis of Principles and Methods. With the growing criticism back home in East Germany, it is clear that he saw the conference as an opportunity to demonstrate the value and relevance of Marxist art history to the West. In a letter to Manfred Börner of the SED’s Central Committee from September 10, 1964, Feist shared his conference invitation and made a case for his attendance, stressing the need to open a dialogue between the two German states and to “explain and disseminate our convictions coherently and broadly.”27 According to his post-conference report dated January 10, 1965, his lecture was developed in consultation with Humboldt University’s art history faculty and the delegation’s leadership (i.e., Eberhard Bartke).28

Feist later reflected that both the lecture and book sought to illustrate “the superior productivity of a materialistic explanation of art and art history, based on economic and social conditions, and at the same time, especially with regard to the situation in the GDR, to acknowledge the value of the methodological achievements of Wölfflin, Riegl, Panofsky, etc., even for Marxist research.”29 Yet despite these shared objectives, the content of each was likely tailored to the specific contexts of their respective intended audiences in West and East Germany. Unfortunately, we were unable to locate the original lecture manuscript for comparison with the 1966 publication translated in this issue. However, there is some evidence that points to shifts in emphasis between the two.

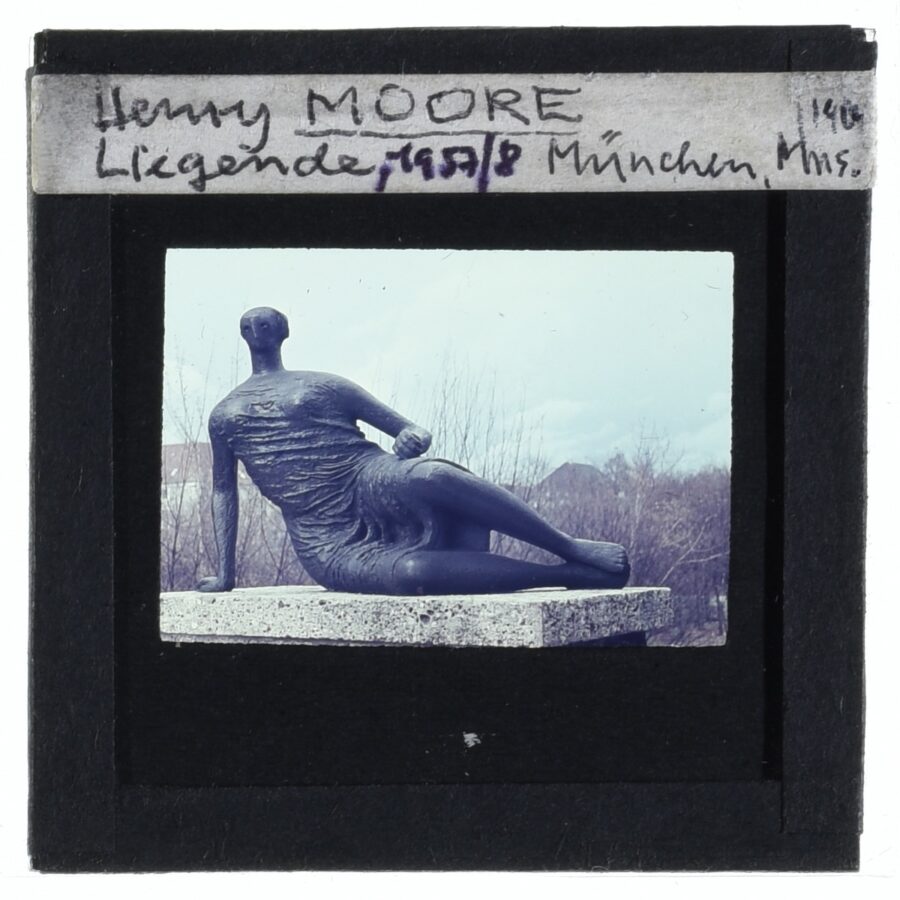

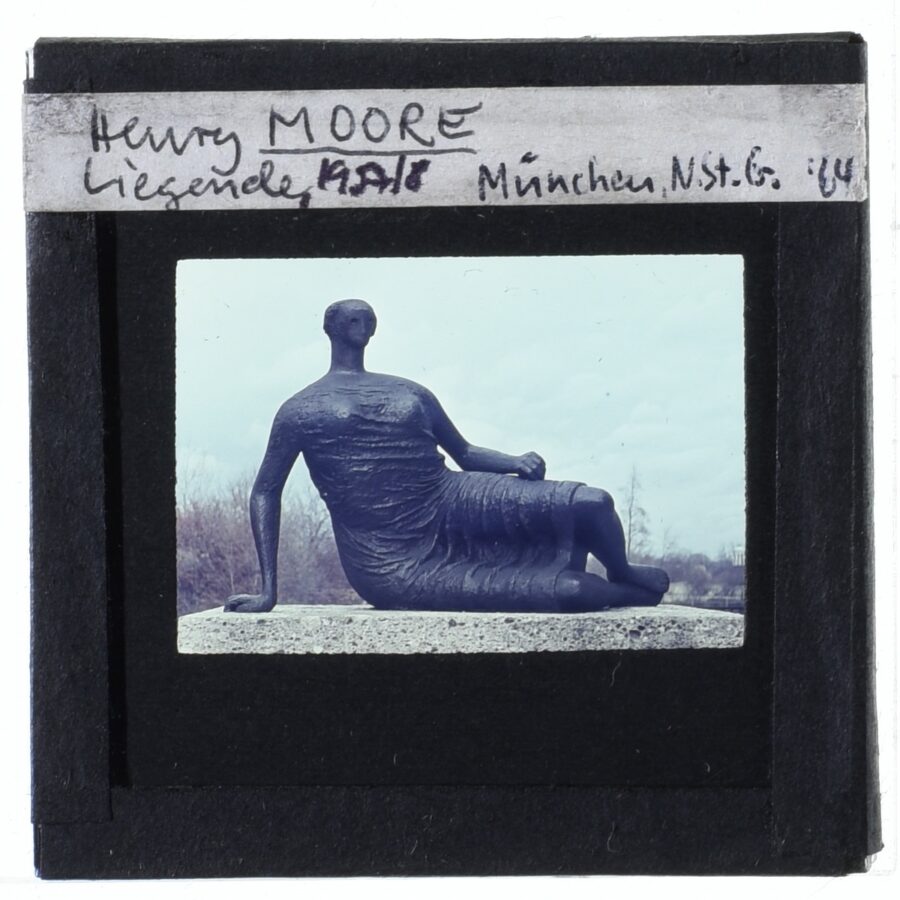

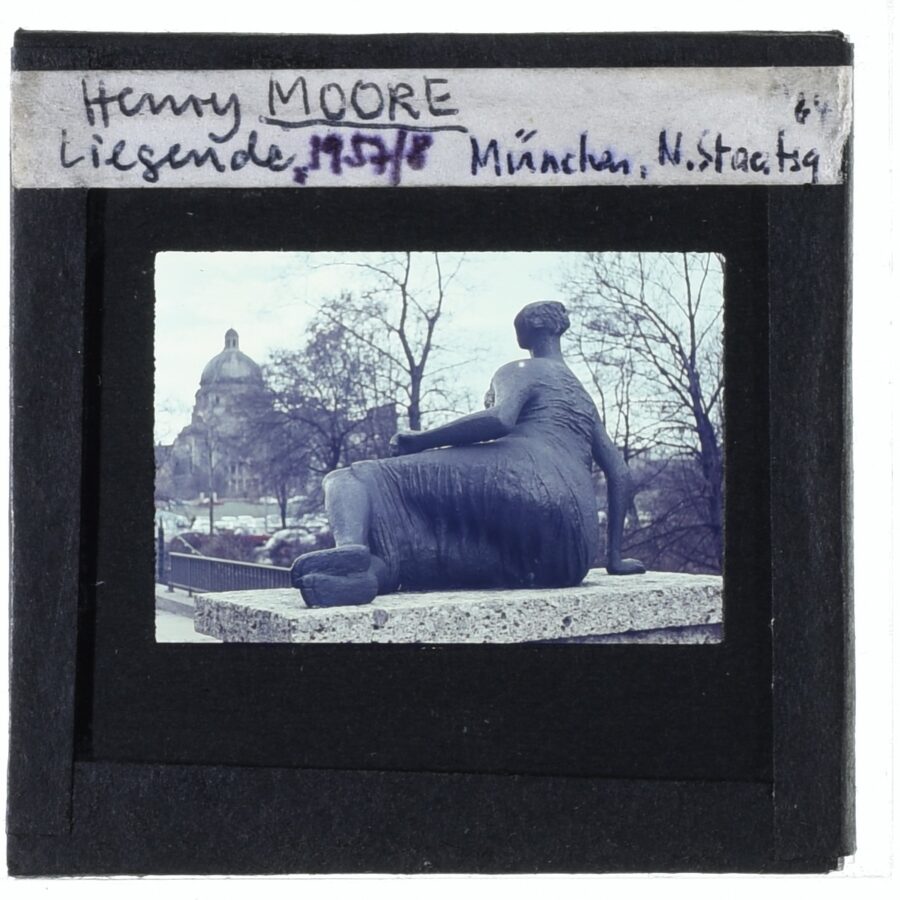

In Doris Schmidt’s report on the conference for the Süddeutsche Zeitung, she highlights Feist’s discussion of the GDR’s contested views on abstract art in his lecture, referring to the so-called “formalism debates” (Formalismusstreit), in which East German artists clashed with party leadership over its condemnation of art that seemingly privileged formal experimentation at the expense of socialist content.30 With palpable disbelief, Schmidt recounts learning from Feist’s lecture that “it is not strictly forbidden [in the GDR] to deal with abstract works of art, such as those of Henry Moore.”31 Several slides from the Humboldt University’s image archive of Moore’s Draped Reclining Woman (1957–58) outside the Haus der Kunst, taken by Feist during his 1964 Munich trip (Figs. 3–5), suggest the artist was indeed on his mind.

We can surmise the potential contours of this discussion from Feist’s Plastik in der DDR, written in the same year, in which Moore is portrayed as free to some extent from the taint of capitalist abstraction. While, in his view, most Western sculpture suffered from “inhumane tendencies toward distortion, destruction, and ultimately the expulsion of the image of humanity (Menschenbild) from art… almost no imaginative sculptor can avoid engaging with the interpenetrations of body and space found in the fascinating work of Henry Moore.”32 Feist’s later essay “Künstler und Gesellschaft” [Artist and Society] expands on these

ideas, in which he asserts that societal conditions and class interests determine the creative opportunities available to artists. Here, he identifies a proto-socialist sensibility in Moore’s abstract work, claiming that it would have eventually evolved into realism had the social circumstances allowed it.33

Tellingly, Moore is not mentioned in Principles and Methods. Feist indirectly touches upon the problem of abstract art when he presents Marxist analysis as a more objective tool for interpreting shifts in artistic forms. He does this by referencing “the pursuit of purity of [artistic] means,” a phrase originally used by Hans Sedlmayr to characterize the transition in modern art from figural representation to abstraction.34 According to Feist, Marxism offers the most effective approach to the evolution of art because it considers the socioeconomic influences on artistic expression, in contrast to Sedlmayr’s focus on aesthetic and cultural decline.

Thus, Feist’s inclusion of Moore’s abstract art in the 1964 lecture was likely a calculated provocation, especially considering that Sedlmayr, an LMU professor already known for his conservative views on modern art and rejection of abstraction, was expected to attend.35 In so doing, he underscored the versatility of Marxist art historical analysis by showcasing its capacity for critical engagement with contemporary art forms that were dismissed by the more rigid and limiting frameworks associated with Sedlmayr. This was a strategic move intended to counteract Western perceptions of East German art history as overly narrow and doctrinaire, affirming instead its intellectual rigor and relevance to a broader art historical discourse.

Several accounts of the conference suggest that Feist largely succeeded in his objective. A report in the LMU’s Student Council newspaper confirmed that “Overall, there was widespread astonishment at how ‘open’ and permeable Marxism is to the findings of bourgeois scientists.”36 In the following issue, a more critical response noted that both “branches” of art history share the same methods and “arrive at the same results based on opposite premises.”37 Schmidt also observed how, during the conference, “it increasingly became clear that adaptation and amalgamation are integral to the Marxist principle of social progress”—though she skeptically suggests such tolerance might “mask a claim to totality.”38

In his own account, Feist celebrated the event’s success in dispelling Western misconceptions of Marxist art historians as dogmatists. Despite some confusion over key Marxist terms and concepts by those he derided as “Western Marxologists,” he claimed the main takeaway of the West German attendees was “the apparently surprising revelation that Marxists know bourgeois science, critically appropriate it and want to preserve and continue its humanist and rationalist traditions through renewal, that Marxists think in a differentiated and independent way and not in a stereotyped way, but recognize in Marxism a guide to their own scientific action, and that they thus arrive at new results.”39

While the Munich lecture targeted external misconceptions in the West, the 1966 publication responded more directly to ongoing internal debates within East Germany. Indeed, in the book’s preliminary remarks, Feist identifies the discipline’s “backwardness” as the main reason for the publication.40 Even if this assertion is merely lip service, Feist’s involvement in the overhaul of art historical higher education only intensified as the book came to print; between 1965 and 1967, he was appointed to several working groups, committees, and advisory boards tasked with developing strategic plans and guidelines that offered new directions for art historical education in the GDR. Through these endeavors, necessary compliance with the SED’s directives was leveraged into an opportunity to revitalize the field.41 A crucial aspect of this process was the critical examination and integration of the discipline’s history within a Marxist framework. As Feist stated in a later reflection,

I wanted to contribute to making art history in the GDR recognizable as a potent continuation of a significant tradition of German art research (Kunstforschung), and at the same time, to fundamentally change it in such a way that it could not only keep up with Western art history in terms of its tasks, theory, and methods but could overtake it.42

Therefore, his mention in the preface of Principles and Methods regarding the conversations about his Munich lecture at Humboldt University and with other colleagues likely refers to his involvement in these working groups and committees dedicated to reforming art historical education.43 Although we can only speculate about the exact changes between the two, it is clear that Principles and Methods was instrumental in Feist’s mission to re-found a pedagogical vision for the discipline in the GDR.44

Principles and Methods on Both Sides of the Wall

Two reviews by Horst Zimmermann and Harald Olbrich indicate that East German art historians readily embraced Feist’s proposals for aligning art history more closely with contemporary Marxist doctrine and socialist politics.45 Zimmermann lauded the book’s potential to stimulate theoretical and methodological discussions on Marxism’s application in art history, citing its thorough presentation and well-developed thesis as vital tools for resolving current misconceptions and debates within the field. Similarly, Olbrich emphasized the timeliness and significance of the text, praising its accessible and principled approach to art history and, most importantly, its successful communication of Marxist perspectives to a wider audience. He also commended Feist for grounding his work in the research of his German and international peers, effectively legitimizing Marxist Kunstwissenschaft as a substantive field of study rather than a radical break with the past or a simple exercise in Marxist philosophy of history.

Despite this initial acclaim, Principles and Methods garnered little critical attention over the following decades in either East or West Germany. This somewhat surprising lack of interest may be explained by the fact that Feist sought to paint a holistic picture of the discipline, one that prioritized continuity and coherence over bald-faced polemic. We note the strong contrast between his larger methodological claims and his avoidance of contentious topics, such as the question of abstract art or Marx’s views on ideology. One could even argue that he did not write the text as a tool for art historians, but as a guidebook for bureaucrats and students. Although it is often referenced in East German scholarship, these are usually cursory citations. The political historian Peter Schuppan, for example, cites Feist’s text in a footnote to his discussion of art history’s contributions to a Marxist theory of cultural history.46

Nevertheless, its frequent citation in East German dissertations and habilitation theses attests to its methodological currency. Max Kunze, for instance, directly engages with Feist’s discussion of influence as an active, progressive process in his analysis of classical Greek elements in Roman art during the Augustan period.47 Kunze uses Feist’s concept to argue that Roman artists selectively assimilated Greek styles rather than merely imitating them, thereby advancing the development of their own artistic expression. Furthermore, the East German government’s art education curriculum from 1975 included Principles and Methods as required reading for art history coursework, alongside two art history encyclopedias and two anthologies of artists’ writings.48

Principles and Methods also gained notable traction among non-German Marxists, with citations in scholarly works from countries like Hungary, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, Bulgaria, and Italy.49 Many of these utilized Feist’s work to address pressing methodological concerns facing the discipline in their respective countries. For example, Sieghard Kozel, writing in Upper Sorbian (!), draws directly from Feist’s text in his essay on the state of Sorbian art criticism.50 He emphasizes the need for a detailed examination of an artwork’s distinct characteristics and the context in which it was produced to ensure that (here, quoting Feist) “the unity of theme, form, and content is always maintained.”51 Moreover, a Polish translation was included in a 1976 anthology edited by Jan Białostocki of U.S. and European essays on art historical method and theory.52 Feist is the only East German art historian included in the collection, with his work categorized under the heading “Problems of Interpretation” alongside translations of essays by Meyer Schapiro, Ernst Gombrich, Berthold Hinz, and Rudolf Zeitler.53

The most insightful perspective on the book’s reception comes from a later reflection by one of Feist’s former students, Fritz Jacobi.54 Jacobi noted his initial skepticism as a young reader of Feist’s assertion of philosophical materialism as the basis of art history and theory—a claim he found to be more dogmatic than supported by evidence. Nevertheless, he acknowledged that the arguments were valued at the time for challenging both the external perceptions of and internal orthodoxies within Marxist scholarship. Jacobi also remarked on the text’s impact on debates over the relationship between content and form, praising, in particular, how Feist not only “calls for cooperation with neighboring academic disciplines… but also opens the gates wide to the whole of art studies to date and its concise representatives.”55

It is precisely this openness of Principles and Methods that may explain its surprisingly wide dissemination outside the Eastern Bloc. Shortly after its release, the book was advertised in the recent literature sections of several West German academic journals.56 In addition to numerous West German publications, it was also mentioned in U.S. and Belgian ones, and by 1973, it was even listed in the holdings of Harvard University’s Widener Library.57 However, despite its international presence, in-depth analysis of the text was rather limited in the West. In West Germany, it was almost entirely cited in passing, usually in a laundry list of examples of Marxist or, more generally, social art history.58

One notable exception is Werckmeister’s “Marx on Ideology and Art,” in which he outlines the failure of twentieth-century Marxist scholars to accept Marx’s position that art is part of ideology.59 He cites Feist in a footnote for the following statement: “It cannot be denied that great art was being produced under capitalism, but no important artist acclaimed capitalism in its true character.”60 Here, he references a passage where Feist leverages Marx’s assertion that capitalism is inherently hostile to art to argue that “great art is only possible if it goes against capitalist conditions.”61 Werckmeister, however, contends that the notion that “true” art can criticize its capitalist context represents a fundamental reinterpretation of Marx’s dictum. He argues that this has led to further misunderstandings, mostly among Western Marxists, who believe that art can transcend its capitalist conditions and has the potential to enact revolutionary change.62 For Werckmeister, even art under socialism is compromised by commodification and is thus antagonistic to social progress. Nonetheless, Feist’s own reading of Marx would have likely led him to disregard Werckmeister’s interpretation as “vulgarism,” advocating instead for art’s capacity to influence and cultivate societal transformation.

In 1993, nearly three decades after the publication of his book, Feist reflected on its methodological contributions. To his astonishment, he acknowledged that he could find no reason “to fundamentally deviate from the historical, art theoretical, and methodological concept.”63 However, he also criticized the text’s idealized views on the impact of socialism on art and overly optimistic beliefs in Marxism-Leninism. Moreover, he reconsidered his earlier conviction in a singular, comprehensive methodology for art history, noting, “Today, I am fully aware that the subject only advances with a diversity of methods and as a sum of different partial insights and interpretations.”64 While such a claim may seem at odds with his explicit advocacy for methodological diversity in Principles and Methods, Feist here appears to distance himself from the assertion that scholarly objectivity is guaranteed by partisanship (Parteilichkeit) with the working class, as well as from the belief in materialism’s direct access to reality.65

Feist’s Commitments

These reservations notwithstanding, Principles and Methods offers a range of methodological insights that deserve further attention. Very much a faithful partisan of the GDR’s “cultural revolution” (Kulturrevolution)—a state-orchestrated effort to shape socialist consciousness—Feist was complicit in the SED’s repressive cultural politics and, in return, was granted unparalleled privileges, as his impressive travel record attests.66 But this does not mean we should dismiss Principles and Methods outright as irredeemably compromised by its ideological commitments. After all, Feist did not always toe the party line and occasionally came under fire by GDR authorities for his unorthodox positions.67 Just as a recent wave of scholarly appraisals has challenged enduring misconceptions of GDR artists as ideologically compromised and artistically inferior, the scholarly output of GDR art historians like Feist also merits a more nuanced consideration.68

It is important to note that the perceived lack of methodological contributions from GDR art historians can be attributed to the stringent constraints imposed on them, both in terms of their adherence to Marxist commitments and their opportunities for publication. Soon after the release of Principles and Methods, the implementation of the Third University Reform resulted in the regulation of art historical research by the SED’s central planning committees.69 But even before these reforms, informal control and surveillance mechanisms already curtailed controversial scholarship. The sustained criticism of art history also prevented the establishment of a flagship academic journal, limiting the advancement of broader methodological debates.70 The shift toward mass “popular education” (Volksbildung) necessitated that art history primarily serve pedagogical purposes and support the creation of socialist art, aiding in the ideological shaping of the “new man.” In his autobiography, Feist remarked that his contributions to education and art criticism prevented him from becoming a recognized expert on a particular subject or artist like his Western counterparts, though he harbored no regrets over this outcome.71 During the International Association of Art Critics (AICA) conference in June 1966, Feist heralded the power of artists to shape the beholder’s consciousness and to “design” a universal image of humanity (Menschenbild), liberated from capitalist alienation.72 In support of the ongoing “cultural revolution,” art history’s task was to supply historical models for emulation rather than to produce innovative scholarship.73 In an undated manuscript from the mid-1960s, Feist described the art historian as a “cultural functionary” who strategically utilizes “practice” as a tool for guiding society’s cultural evolution.74 Owing to these state-imposed restrictions, historical research was not directed toward the academic community but was instead “concealed” within survey books intended for a general audience.75

Methodological reflections may not have been the focus of monograph publications, but they often contained subtle cues that require careful attention. Principles and Methods is perhaps Feist’s most overtly “Marxist” work, but it was not his only theoretical contribution. His conference presentations and articles typically showcase a more diverse engagement with art historical methodologies, often centered on a specific problem or concept. These contributions strike a careful balance between Marxist and traditional art historical terminologies, such as “influence” and “dialectics,” “artist and society,” “the study of motifs” (Motivkunde), or “relations of art” (Kunstverhältnisse).76 Despite their alignment with Western discourses, none of these studies seem to have left a trace on our discipline. Other well-known scholars from the GDR, such as Harald Olbrich, Friedrich Möbius, and Helga Möbius, explored methodological issues, but their work inevitably met the same fate.77 The 1980s, in particular, witnessed a notable variety of publications and approaches focused on underexplored topics that warrant a critical reappraisal.78

The theoretical stakes of Principles and Methods are analyzed in greater detail by Katja Bernhardt in her contribution to the present issue. Therefore, instead of providing a summary of our own, we would like to offer some preliminary remarks on three key commitments of the text that we believe are of particular interest to current art historical debates.

1. Form, Content, and Ideology

One of the key issues that Feist addresses in his text is the relationship between form and content, a topic deeply rooted in the Marxist discourse on the interplay of material base and cultural superstructure. This theoretical problem gained particular urgency in the GDR, where cultural policies required art to conform to socialist values and contribute to the formation of a new consciousness of reality. During the 1950s, this agenda set off the formalism debates mentioned above that decried abstract art’s failure to reflect working-class concerns or the image of humanity (Menschenbild). Although Feist maintains the primacy of content over form in Principles and Methods, he clarifies that this does not negate the latter’s significance, explaining that

The content of an artwork is not tantamount to its theme or subject, as important as this representational aspect of the artwork is. Rather, the content is the meaning that the artist imparts to their theme by means of the design—it is the statement the artist wants to make about the subject, and it can only reach the viewer in the guise of a sensually perceptible form.79

This perspective complicates the established view promoted by cultural bureaucrats that the value of socialist art lies chiefly in its literal depiction of socialist themes and subjects, such as the proverbial steel worker or rugged farmer, suggesting instead that form itself could convey socialist values.

Feist adamantly defended the relative autonomy of art, thus resisting, as Horst Bredekamp put it, the “short-circuiting of form and ideology.”80 And yet he also recognized the more subtle ideological possibilities of style. Even when exploring traditional socialist motifs, he insisted on a nuanced, form-conscious approach. For example, in his unpublished paper “Einige Probleme des sozialistischen Menschenbildes,” he makes a case for the “realistic typification” of individuals over mere “standardization” and for a psychological portrayal that faithfully captures unalienated existence within socialist society.81

Principles and Methods also underscores the importance of cultural heritage (Kulturerbe), showing how artists from different eras drew upon their respective artistic legacies to shape their unique forms of expression.82 It argues that this is not an act of slavish imitation but a dynamic reinterpretation of past influences that expresses contemporary realities. In this regard, Feist can be connected to several art historians, who, starting in the 1950s and ‘60s, revisited cultural heritage to reformulate the prescriptive relationship between content and form, thereby equipping artists with the conceptual tools to produce art that conformed to the tenets of socialist realism without sacrificing their artistic integrity.83

2. Kunstwissenschaft and “Operative” Art History

Within the GDR’s academic infrastructure, “art history” (Kunstgeschichte) was classified as a branch of the more expansive field of “art science” (Kunstwissenschaft), which also encompassed art theory, art criticism, and cultural politics. The Lexikon der Kunst—East Germany’s massive art encyclopedia project—defined Kunstwissenschaft as “a discipline within the social sciences that researches, presents, and actively helps to develop the specific forms of human aesthetic activities (appropriation) that manifest as art.”84 It was expected to evolve into “the science of predicting, planning, managing, and organizing the processes and communications related to art within socialist society,” thereby facilitating closer engagement with contemporary art and popular education.85 In contrast, Kunstgeschichte was more narrowly defined as being concerned with the “objective, varied yet systematically governed, and infinitely evolving process of artistic development, which stands as a relatively independent facet of human history and its material and intellectual culture.”86 This methodological and political subordination of art history to the objectives of the “cultural revolution” was institutionalized during the Third University Reform, resulting in what the architectural historian Ernst Badstübner described as the lasting “dilution” of the art historical profession.87

Despite such efforts to incorporate Marxist tenets into art history, the methodological framework of Kunstwissenschaft remained relatively vague. In Principles and Methods, Feist outlined his focus on “art’s historical development,” thus aligning with the discipline’s more traditional discourses.88 However, he also emphasized that, despite art’s relative autonomy from determinism, art historians are nevertheless obligated to maintain “partisanship” with the working class in order to fulfill their social responsibilities.89 Feist described this commitment to political practice as the “operative” dimension of art history, carefully distinguishing it from “vulgar” Marxist analyses of the historical past.90 He criticized these vulgar interpretations for their simplistic correlation between the economic base and the superstructure of a collective mindset and for their uncritical praise of the superiority of the socialist present over the past.

Operative art history offers a more subtle approach, mobilizing a specifically aesthetic mode of “appropriating the world” (Weltaneignung), as prescribed by Marx, in order to reshape socialist identity.91 In his preliminary draft outlining a new concept of art history (discussed above), Feist elaborates on this method, emphasizing the dual function of “ratio/emotio” within Kunstwissenschaft: “The science of art can raise consciousness of the spontaneous processes of enjoying and creating art, and thus deepen, expand, and develop them in a planned manner. Knowledge serves a right feeling.”92 Even after Germany’s reunification, Feist generally continued to embrace his approach to history, unlike some of his former colleagues, such as Harald Olbrich, who decried the need to “obsessively and selectively search for imagined historical analogies.”93 With its emphasis on social outreach and impact, “operative” art history brings to light the fraught legacy of recent appeals for “engaged” art historical practices and reappraisals of “vulgar” theoretical models.94 For instance, McKenzie Wark has advocated for a return to “vulgarism,” emphasizing, in particular, everyday artistic practices—an echo of the GDR’s promotion of amateur art (Laienkunst)—to reinvigorate working-class resistance.95 Although these initiatives stem from positions of solidarity with marginalized communities rather than authoritarian cultural mandates, GDR Kunstwissenschaft might nevertheless provide a useful case study of how to strike a balance between activism and scholarly work.

3. Artistic “Adoption” and Trans-Culturalism

Feist was committed to European art historical discourses, often prioritizing “bourgeois” writers over their non-Western counterparts. In his extensive recommended reading list at the end of Principles and Methods, well-known European art historians outnumber Soviet scholars.96 Rather unexpectedly, Aby Warburg—son of an haute bourgeoisie Hamburg banking dynasty—is portrayed as an important advocate for art’s “external” determination. Even more curiously, Hans Sedlmayr figures as a proponent of dialectic reasoning.97 Moreover, Feist’s emphasis on the importance of art’s social and economic contexts over ethnic identities did not deter his exploration of “national or tribal characteristics,” deeply problematic terms that originated in early twentieth-century discourses on the “geography of art” (Kunstgeographie) and were later weaponized by völkisch race theories.98 Despite these ambivalences, Feist proposed a remarkably progressive methodological framework for analyzing transcultural exchanges that was likely inspired by his longstanding interest in the migration and transformation of artistic motifs across history and cultures.99

At the same time, his approach was also indebted to the premises of Marxist internationalism and the pluralist cultural policies of the Soviet Union.100 The Lexikon der Kunst conceived of Marxist Kunstwissenschaft as an interdisciplinary approach to studying art from a “world-historical” perspective.101 Dismissing the passive concept of “influence” (Einfluss) as ideological and racist, Feist instead proposed that the interplay of cultures should be conceived as an active “adoption” (Übernahme), a process motivated by materialistic principles to solve specific societal issues.102 His reinterpretation of “world art” aimed to counter biological and “irrational” accounts of art history that fetishized abstract laws of evolution over collective struggle. Even though his terminology is decidedly Eurocentric, Feist’s model exhibits notable parallels with George Kubler’s Shape of Time, which was published two years before his talk and similarly prioritized cultural problem-solving over biographical and biological explanations.103 Despite his striking lack of political and social awareness, Kubler has recently been reassessed for his potential contributions to postcolonial analysis;104 Feist and his socialist framework, on the other hand, remain understudied. Foregrounding the artistic agency of the colonized and the repressed, Feist’s unequivocally political account of cultural exchange represents an early counterpoint to hegemonic narratives of center and periphery that merits further attention.105

With these preliminary remarks, we hope to set the stage for a much-needed reconsideration of the histories of Marxist methodology that have been marked by an overly rigid division between the “critical” legacies of the West, on the one hand, and the “ideological” baggage of the East, on the other. Positioned uneasily at the edge of the Iron Curtain, Principles and Methods provides a key test case for complicating prevailing accounts of the period and for highlighting the historical complexities of dialogue across the German divide as well as the methodological richness of the Marxist paradigm more generally.

This special issue is organized into two sections, one centered on Feist’s Principles and Methods and the other on its larger context within the socialist world. The first part includes our English translation of Principles and Methods, supplemented by critical annotations that gloss key terms and concepts. Additionally, the contributions in this section by Nicos Hadjinicolaou and Katja Bernhardt provide important context on the origins of Feist’s text. Hadjinicolaou’s autobiographical account was written in response to a series of questions we posed regarding the genesis and influence of Principles and Methods. He chronicles his motivations for organizing the 1964 Munich conference, the political obstacles he encountered, the reception of Feist’s lecture, along with its limited impact on Western Marxist debates. Complementing his narrative, he has graciously provided a curated selection of pivotal documents from his personal collection. Bernhardt thoroughly dissects Principles and Methods in her historiographic essay, charting its theoretical maneuvers and examining how the text strategically positioned art history between its “bourgeois” heritage and Marxist doctrine. Her analysis of its “diplomatic” qualities reveals the precarious balance it sought to achieve in order to reconcile the demands of Marxist theory, the autonomy of art history as a discipline, and the practical considerations of contemporary art policy.

While the initial section focuses on the specifics of East German art historical practice as outlined in Feist’s text, the second section details its connections within and beyond the Eastern Bloc.

April Eisman’s essay brings attention to the overlooked category of East German experimental art, illustrating how Feist’s ideas reverberated in the GDR long after the text was published. She focuses on the works displayed at the 1988 “Blue Wonder” exhibition by artists Angela Hampel and Steffen Fischer, who used their platform to engage with controversial societal issues, especially environmental concerns. Despite their critical stance, these works were showcased in official channels and received largely positive feedback, thus complicating the simplistic divide between East German dissident and state artistic cultures. Through her analysis, Eisman demonstrates how critical art was accepted by cultural authorities as a tool of collective societal engagement and improvement, following the blueprint established twenty years earlier by Feist.

The contributions from our two other authors help chart the integration of GDR art historical discourses within the wider socialist world. Centering points of contact beyond the traditional strongholds of Europe, China, and the Soviet Union, these two case studies underscore the limitations of isolationist accounts of the Eastern European “bloc” perpetuated by Western Cold War rhetoric, bringing much-needed attention to the role of the Global South in socialist academic cultures and Marxist thought more broadly.

Douglas Gabriel’s essay explores North Korea’s steadfast adherence to traditional artistic principles in the face of an evolving global socialist aesthetics during the 1950s, shedding light on the wider context of the GDR’s formalism debates that echoes throughout Principles and Methods. Focusing on the artist Mun Hak-su’s response to the 1959 international exhibition “The Art of Socialist Countries” in Moscow, Gabriel examines North Korea’s resistance to the encroaching tendencies of Western modernism, especially abstraction, in the art of other socialist nations. He asserts that this critical stance exemplified a broader ideological struggle within socialist art discourse, where the embrace of abstraction was seen as a threat to the ideological clarity and collective orientation of socialist realism. By analyzing North Korea’s fraught reception of Eastern European art, he illustrates the cultural and ideological divergences within socialist artistic discourses during the Cold War period.

Finally, Megan Sullivan charts the emergence of a social theory of art in 1970s Latin America that offered an alternative to the more traditional Marxist art history advocated by Feist. Without entirely abandoning ideological analysis, this approach attempted to rectify its perceived limitations by emphasizing the material aspects of art’s production, circulation, and consumption. According to Sullivan, scholars like Mirko Lauer and Néstor García Canclini foregrounded the materiality of art in their critical analysis, thereby providing a framework that more carefully attended to art’s social functions, even if, at the same time, it also failed to account for how subjective experiences of art or the artist’s intentions also shape its meaning.

By situating Feist within wider networks of East German, North Korean, and Latin American stakeholders and prioritizing connections over isolation, a richer and more diverse account of Marxism’s challenge to art history emerges, one that dismantles widespread assumptions of ideological uniformity. “Our difficult, beautiful subject,” as Feist once called art history, proved surprisingly resilient against ideological appropriation and served as a critical arena for advancing Marxist methodologies across the socialist world. To consign GDR art history and Marxist thought more broadly then to the “dustbin of history” means failing to recognize their value and their risk for our late capitalist society, even as it hurtles towards a future with no ostensible alternative.

We are very grateful to Daniel Marcus, Jennifer Nelson, and Daniel Spaulding for their patient support and keen editorial guidance in the publication of this special issue. We are also deeply indebted to the many colleagues, friends, and friends of friends who provided feedback at various stages of this project, helped us track down sources and people, or shared their expertise on Marxist thought and East German (academic and bureaucratic) nomenclature, among them Hendrik and Julia Bärnighausen, Ralf Bartholomäus, Armin Bergmeier, Horst Bredekamp, April Eisman, Eliza Garrison, Nicos Hadjinicolaou, Lisa Jordan, Henry Kaap, Morgan Ng, Joanna Olchawa, Andrew Sears, Georg Schelbert, Megan Sullivan, Michael Tymkiw, and Matthew Vollgraff. Many thanks as well to the staff and team at the Special Collections of the Getty Research Institute, the Media Library at Humboldt University of Berlin, and the Fachschaft of Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich. We would also like to thank Brett Savage for copy-editing this introduction. This special issue benefited from the research support of the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Fellowship for Assistant Professors at the Institute for Advanced Study.

- The title of this introduction comes from a phrase found in Peter H. Feist, “Methodensuche und Erbefragen in der Kunstwissenschaft der DDR vom Ende der 1950er bis zum Beginn der 1970er Jahre [1993],” in Peter Betthausen and Michael Feist, eds., Nachlese: Aufsätze zu bildender Kunst und Kunstwissenschaft (Berlin: Lukas Verlag, 2016), 49. Unless otherwise noted, all translations are our own.

- [1] Many thanks to the late O.K. Werckmeister for sharing this photograph with us (email message to authors, April 2, 2021) and to Gabi Dolff-Bonekämper for clarifying its context (email message to authors, June 30, 2023).

- [2] Peter H. Feist, “Einige Probleme des sozialistischen Menschenbildes in der bildenden Kunst der DDR,” summer 1963, unpublished manuscript, Getty Research Institute, Special Collections, DDR Collections, 940002 (henceforth GRI 940002), series 10, box 55, folder 8, 3.

- [3] Peter H. Feist, Plastik in der Deutschen Demokratischen Republik (Dresden: Verlag der Kunst, 1965), 9–10.

- [4] Peter H. Feist, “Gefährdung und Bewahrung des Menschenbildes. Zur Geschichte der deutschen Plastik im 20. Jahrhundert,” Bildende Kunst 9 (1961), 233–41.

- [5] Feist, Plastik in der DDR, 8.

- [6] Peter H. Feist, Prinzipien und Methoden marxistischer Kunstwissenschaft—Versuch eines Abrisses (Leipzig: E.A. Seemann, 1966).

- [7] Peter H. Feist, Principles and Methods of a Marxist Kunstwissenschaft—Attempt at an Outline, trans. Tamara Golan and Felix Jäger, in Tamara Golan and Felix Jäger, eds., Selva 5 (spring 2024), 27–52.

- [8] On the denunciation of GDR education, see: Dirk Oschmann, Der Osten: Eine westdeutsche Erfindung, 2nd ed. (Berlin: Ullstein, 2023), 20–21, 64–67; and, for the replacement of faculty staff and the underrepresentation of East Germans in university leadership positions: Rosalind M.O. Pritchard, Reconstructing Education: East German Schools and Universities after Unification (New York: Berghahn Books, 1999), 152–204; Ilko-Sascha Kowalczuk, Die Übernahme: Wie Ostdeutschland Teil der Bundesrepublik wurde (Munich: Beck, 2019), 129–34.

- [9] For a critical discussion of postcolonial readings, see: Paul Cooke, Representing East Germany Since Unification: From Colonization to Nostalgia (Oxford: Berg, 2005), 1–26. For an early “colonial” contextualization, see also: Dorothy Rosenberg, “The Colonization of East Germany,” Monthly Review 43 (1991), 14–33.

- [10] See: Andrew Port, “The Banalities of East German Historiography,” in Mary Fulbrook and Andrew Port, eds., Becoming East German: Socialist Structures and Sensibilities after Hitler (New York: Berghahn Books, 2013), 1–30.

- [11] Elaine Kelly and Amy Wlodarski, “Introduction,” in Elaine Kelly and Amy Wlodarski, eds., Art Outside the Lines: New Perspectives on GDR Art Culture (Amsterdam: Rodopi, 2011), 1.

- [12] A complete list of Feist’s publications can be found in: Betthausen and M. Feist, eds., Nachlese, 136–98.

- [13] Peter H. Feist, Hauptstraßen und eigene Wege: Rückschau eines Kunsthistorikers (Berlin: Lukas Verlag, 2016), 28–31.

- [14] The Free German Youth movement’s shift to an explicitly socialist organization took place over the course of the late 1940s and early 1950s. See: Ulrich Mählert and Gerd-Rüdiger Stephan, Blaue Hemden—Rote Fahnen: Die Geschichte der Freien Deutschen Jugend (Opladen: Leske + Budrich, 1996).

- [15] Feist, Hauptstraßen, 33–48.

- [16] Ibid., 36.

- [17] Peter H. Feist, “Der Tierbezwinger. Geschichte eines Motivs und Probleme der Stilstruktur von der altorientalischen bis zur romanischen Kunst” (PhD dissertation, Universität Halle-Wittenberg, 1958).

- [18] Feist, Hauptstraßen, 92–96, 105–7. While travel was greatly restricted for most East Germans in the initial years after the building of the Wall, this marked a period of relative openness for Feist as part of a programmatic effort to enhance the reputation of the GDR through cultural relations abroad.

- [19] Heinz Bebernis et al., “Wir brauchen eine neue Konzeption der Kunstgeschichte. Offener Brief an die Kunstwissenschaftler, die Kunstkritiker und Mitarbeiter der Galerien, Museen und kunstwissenschaftlichen Institute der Deutschen Demokratischen Republik,” Neues Deutschland, November 13, 1962.

- [20] Untitled manuscript, December 20, 1962, GRI 940002, series 10, box 57, folder 2. We were not able to ascertain whether this letter was sent to particular parties or published in a newspaper. A response to the open letter by Friedrich Möbius was published in Neues Deutschland, but while some of the content is similar to the draft prepared by Feist, it is much less diplomatic in tone and much more specific regarding the particular situation at the University of Jena, where Möbius was based. Friedrich Möbius, “Fundgrube für die Wissenschaft. Kunstwissenschaftler antworten auf den offenen Brief der bildenden Künstler,” Neues Deutschland, December 21, 1962.

- [21] For these debates, see: Thomas Klemm, Keinen Tag ohne Linie? Die kunst- und gestaltungstheoretische Forschung in der DDR zwischen Professionalisierung und Politisierung (1960er bis 1980er Jahre) (Munich: Kopaed, 2012), 58–72.

- [22] On the criticisms and pedagogical reforms at Humboldt University’s Institute of Art History, see: Christof Baier, “‘…befreite Kunstwissenschaft.’ Die Jahre 1968–1988,” in Horst Bredekamp and Adam S. Labuda, eds., In der Mitte Berlins. 200 Jahre Kunstgeschichte an der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin (Berlin: Reimer Verlag, 2010), 373–90; Sigrid Brandt, “Auftrag: marxistische Kunstgeschichte. Gerhard Strauss’ rastlose Jahre,” in Bredekamp and Labuda, eds., In der Mitte Berlins, 363–72; Ulrich Reinisch, “Das Kunstgeschichtliche Institut der Humboldt-Universität 1946–1989,” in Rüdiger vom Bruch and Heinz-Elmar Tenorth, eds., Geschichte der Universität Unter den Linden 1810–2010, vol. 6: Praxis ihrer Disziplinen: Selbstbehauptung einer Vision, ed. Heinz-Elmar Tenorth (Berlin: Akademie Verlag, 2010), 389–404.

- [23] Reinisch, “Das Kunstgeschichtliche Institut der Humboldt-Universität,” 397.

- [24] Feist, Hauptstraßen, 92; Brandt, “Auftrag: marxistische Kunstgeschichte,” 366–67.

- [25] Peter H. Feist, “Zu einer Konzeption der Kunstwissenschaft in der DDR in der Periode des umfassenden Aufbaues des Sozialismus,” c. 1963/1965, unpublished manuscript, GRI 940002, series 10, box 57, folder 3, 3–4; Eberhard Bartke to Albrecht Dohmann, February 21, 1964, GRI 940002, series 49, box 301, folder 9; Peter H. Feist to Eberhard Bartke, February 23, 1964, GRI 940002, series 10, box 55, folder 8.

- [26] Feist, “Zu einer Konzeption der Kunstwissenschaft in der DDR,” 1–2.

- [27] Peter H. Feist to Manfred Börner, September 10, 1964, GRI 940002, series 10, box 57, folder 2.

- [28] Peter H. Feist to the State Secretariat for Higher and Technical Education, January 10, 1965, GRI 940002, series 10, box 57, folder 2.

- [29] Peter Feist, “Die Kunstwissenschaft in der DDR,” Kunst und Politik: Jahrbuch der Guernica-Gesellschaft 8 (2006), 22.

- [30] The foundational study on the doctrine of socialist realism and the fraught legacy of modern art in the GDR is Ulrike Goeschen, Vom Sozialistischen Realismus zur Kunst im Sozialismus: Die Rezeption der Moderne in Kunst und Kunstwissenschaft der DDR (Berlin: Duncker & Humblot, 2001).

- [31] Doris Schmidt, “Marxistische Kunstwissenschaft. Zu einer Diskussion in München,” Süddeutsche Zeitung, November 23, 1964.

- [32] Feist, Plastik in der DDR, 13.

- [33] Peter H. Feist, “Künstler und Gesellschaft,” in Künstler, Kunstwerk und Gesellschaft: Studien zur Kunstgeschichte und zur Methodologie der Kunstwissenschaft (Dresden: VEB, 1978), 12.

- [34] Feist, Principles and Methods, 44; Hans Sedlmayr, Art in Crisis: The Lost Centre, trans. Brian Battershaw (London: Hollis & Carter, 1958), 87, 173. See also: Hans Sedlmayr, Die Revolution der modernen Kunst (Hamburg: Rowohlt, 1955), esp. 16–69.

- [35] Nicos Hadjinicolaou to Peter H. Feist, August 26, 1964, private collection of Nicos Hadjinicolaou.

- [36] Hans Günther, “Marxistische Kunstinterpretation: Zu einer mutigen Veranstaltung,” Information: AStA der Universität München, vol. 8, no. 7 (1964), 6.

- [37] Detlef Hoffmann, “Marxistische Kunstinterpretation: Ein Leserbrief zu einem gleichlautenden Artikel in inf. 7/64 S. 6 von Hans Günther,” Information: AStA der Universität München, vol. 9, no. 1 (1965), 6.

- [38] Schmidt, “Marxistische Kunstwissenschaft.”

- [39] Peter H. Feist, “Ist eine isolierte zeitfreie Kunst möglich? Marxistische Kunstwissenschaftler vor Münchener Studenten,” Humboldt-Universität, no. 2, January 27, 1965.

- [40] Feist, Principles and Methods, 34.

- [41] In February 1965, Feist worked on drafting a “perspective plan” for the field with VBKD’s specialist group for art history (run jointly with the Ministry of Culture). The tasks for art history formulated in the document were approved by the Cultural Department of the SED that spring and subsequently used to establish an advisory board for art history at the Ministry of Culture that would work in tandem with the State Secretariat for Higher and Technical Education to formulate and implement research and teaching directives at art history institutes. In January 1966, he was appointed by the State Secretariat for Higher and Technical Education to a working group on theoretical and methodological problems of art studies, through which he worked on drafting another “perspective plan.” Moreover, between 1967–68, he led the working group in charge of drafting the so-called “prognosis plans” that were to be used in the implementation of the Third University Reform at the HU’s Art History Institute. Waltraut Westermann to Peter H. Feist, February 8, 1965, GRI 940002, series 10, box 59, folder 1; Klaus Weidner (advisor in the SED’s Cultural Department), “Die nächsten Aufgaben bei der Entwicklung der Kunstwissenschaften,” March 22, 1965, GRI 940002, series 49, box 301, folder 9; Gudrun Freitag to Peter H. Feist, January 1, 1966, GRI 940002, series 10, box 57, folder 2.

- [42] Feist, “Methodensuche und Erbefragen,” 43.

- [43] Feist, Principles and Methods, 26.

- [44] For further information, see Katja Bernhardt’s essay in this special issue.

- [45] Horst Zimmermann, review of Prinzipien und Methoden marxistischer Kunstwissenschaft, by Peter H. Feist, Neue Museumskunde, vol.11, no. 1 (1968), 100–101; Harald Olbrich, review of Prinzipien und Methoden marxistischer Kunstwissenschaft, by Peter H. Feist, Deutsche Zeitschrift für Philosophie, vol.16, no. 2 (1968), 263–67.

- [46] Peter Schuppan, “Marx und Engels über Kultur und Kulturentwicklung. Theoretische Grundlagen für eine Gegenstandsbestimmung der marxistisch-leninistischen Kulturgeschichtsschreibung,” Jahrbuch für Volkskunde und Kulturgeschichte 19 (1976), 11.

- [47] Max Kunze, Die historischen und ideologischen Grundlagen des Klassizismus-Phänomens in der Reliefkunst der frühen römischen Kaiserzeit (PhD dissertation, Humboldt University, 1974), 10–11. See also: Max Kunze, “Ideologische und künstlerische Voraussetzungen des frühkaiserzeitlichen Klassizismus – Anfänge der klassizistischen Reliefkunst in Rom,” Wissenschaftliche Zeitschrift der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin. Gesellschafts- und sprachwissenschaftliche Reihe, vol. 25, no. 4 (1976), 489–97.

- [48] Ministerium für Volksbildung and Ministerium für Hoch- und Fachschulwesen, Lehrprogramme für die Ausbildung von Diplomlehrern der allgemeinbildenden polytechnischen Oberschulen im Fach Kunsterziehung, May 1975, GRI 940002, series 10, box 57, folder 1, 26.

- [49] Levárdy Ferenc, “Henszlmann alkotó egyénisége,” Művészettörténeti Értesítő 18 (1969), 193–200; Giuseppe Prestipino, La controversia estetica nel marxismo (Palermo: Palumbo, 1974), 17; Lech Grabowski, “Świadomość artystyczna i praktyka,” Przegląd Humanistyczny, vol. 19, no. 8 (1975), 117–23; Ignat Florian Bociort, Teoria progresului literar-artistic (Bucharest: Editura științifică si enciclopedică, 1975), 52; Lubos Hlavácek, “K metodológii teórie a dejiny výtvarných umení III.,” Estetika, vol. 18, no. 2 (1981), 65–81; Jossif Konforti, “Sporŭt za teatŭra prez Vŭzrazhdaneto,” Problemi na izkustvoto 1 (1984), 22–28. Many thanks to Joanna Olchawa for her help reading and summarizing many of these Eastern European texts, as well as the ones cited below in footnotes 50 and 52.

- [50] Sieghard Kozel, “Kritiske wo serbskej kritice,” Rohzlad, vol.21, no. 12 (1971), 457–62. Upper Sorbian is a West Slavic language spoken by the Sorbs, a minority ethnic group indigenous to the Lusatian region of Germany.

- [51] Kozel, “Kritiske wo serbskej kritice,” 461–62.

- [52] Peter H. Feist, “Zasady i metody marksistowskiej nauki o sztuce. Zarys problematyki,” trans. Małgorzata Łukasiewicz, in Jan Białostocki, ed., Pojęcia, problemy, metody współczesnej nauki o sztuce: dwadzieścia sześć artykułów uczonych europejskich i amerykańskich (Warsaw: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe, 1976), 390–423.

- [53] The following essays are included in this section of the anthology: Meyer Schapiro’s “On Some Problems in the Semiotics of Visual Art” (1972), Ernst Gombrich’s “In Search of Cultural History” (1970), Berthold Hinz’s “Der Bamberger Reiter” (1970), and Rudolf Zeitler’s “Kunstgeschichte als historische Wissenschaft” (1967).

- [54] Fritz Jacobi, “Inhalt und Form. Zu Peter H. Feists Publikation ‘Prinzipien und Methoden marxistischer Kunstwissenschaft’ von 1966,” Sitzungsberichte der Leibniz-Sozietät der Wissenschaften zu Berlin 132 (2017), 19–25.

- [55] Jacobi, “Inhalt und Form,” 23.

- [56] For example: Hugo Schnell, “Schrifttum,” Das Münster: Zeitschrift für christliche Kunst und Kunstwissenschaft 11/12 (1966), 483; “Bei der Redaktion eingegangene Neuerscheinungen,” Kunstchronik, vol. 2o, no. 4 (1967), 116.

- [57] Roger H. Marijnissen, “Beeldende kunst en samenleving” Kultuurleven, vol. 41, no. 7 (September 1974), 740–61; Erik Larsen, Calvinistic Economy and 17th Century Dutch Art (Lawrence: University of Kansas Publications, 1979), vii; Harvard University Library, Sociology, vol. 2, Widener Library Shelflist, vol. 46 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1973), 175.

- [58] Heinrich Lützeler, Kunsterfahrung und Kunstwissenschaft: Systematische und entwicklungsgeschichtliche Darstellung und Dokumentation des Umgangs mit der bildenden Kunst, vol. 2 (Munich: Verlag Karl Alber, 1975), 904–6; Udo Kultermann, Kleine Geschichte der Kunsttheorie (Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, 1987), 159; Norbert Schneider, “Kunst und Gesellschaft: Der sozialgeschichtliche Ansatz,” in Hans Belting et al., eds., Kunstgeschichte: Eine Einführung (Berlin: Dietrich Reimer Verlag, 1986), 244–63; Leopold D. Ettlinger, “Kunstgeschichte als Geschichte,” Jahrbuch der Hamburger Kunstsammlungen 16 (1971), 7–19; Bernd Roeck, Lebenswelt und Kultur des Bürgertums in der frühen Neuzeit (Munich: R. Oldenbourg, 1991), 84.

- [59] O.K. Werckmeister, “Marx on Ideology and Art,” New Literary History, vol. 4, no. 3 (1973), 501–19.

- [60] Werckmeister, “Marx on Ideology and Art,” 510, note 30. In addition to Feist, he also cites: Erhard John, Probleme der marxistisch-leninistischen Ästhetik (Halle: Niemeyer, 1967). John was an East German specialist in aesthetics and cultural theory, but not an art historian per se.

- [61] Feist, Principles and Methods, 44. Emphasis in the original.

- [62] Here, Werckmeister refers specifically to the likes of Francis Klingender, Herbert Marcuse, and Ernst Fischer.

- [63] Feist, “Methodensuche und Erbefragen,” 47.

- [64] Ibid.

- [65] On Parteilichkeit see also: “Kunstgeschichte,” in Harald Olbrich et al., eds., Lexikon der Kunst, vol. 2 (Leipzig: E.A. Seemann, 1976), 787; and, more critically, Baier, “…befreite Kunstwissenschaft,” 373–74.

- [66] For an overview of the “cultural revolution” in the GDR, see: Gerd Dietrich, Kulturgeschichte der DDR, vol. 2: Kultur in der Bildungsgesellschaft 1958–1976, 2nd ed. (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2019), 799–804.

- [67] Feist briefly discusses two early instances of being reprimanded by the Party in: Feist, Hauptstraßen, 70 and 97.

- [68] April A. Eisman, Bernhard Heisig and the Fight for Modern Art in East Germany (Rochester: Camden House, 2018); Seth Howes, Moving Images on the Margins: Experimental Film in Late Socialist East Germany (Rochester: Camden House, 2019); Sara Blaylock, Parallel Public: Experimental Art in Late East Germany (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2022); Sarah E. James, Paper Revolutions: An Invisible Avant-Garde (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2022); and Briana J. Smith, Free Berlin: Art, Urban Politics, and Everyday Life (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2022).

- [69] On the university reform and its impact on art history, see footnote 22, especially, Baier “…befreite Kunstwissenschaft,” 374–81. For Feist’s own recollections of the process, see: Feist, Hauptstraßen, 97–98; and for another eyewitness account: Friedrich Möbius, Wirklichkeit – Kunst – Leben: Erinnerungen eines Kunsthistorikers (Jena: Bussert & Stadeler, 2001), 119–24.

- [70] Ernst Badstübner, presentation at the 22nd Congress of German Art Historians, Aachen, 1990, Kunstchronik, vol. 44, no. 4 (1991), 234–38, here 235; Harald Olbrich, ibid., 228–33, here 230–31; and Jens Semrau, “Zensur in der DDR: Reflexionen und Erfahrungen,” kritische berichte, vol. 23, no. 4 (1995), 49–54.

- [71] Feist, Hauptstraßen, 206.

- [72] Peter H. Feist, “Das Menschenbild als Kriterium des Neuen,” unpublished manuscript, June 8, 1966, GRI 940002, series 10, box 55, folder 8, 3.

- [73] On the identification of “models,” see: Feist, “Einige Probleme des sozialistischen Menschenbildes.”

- [74] Peter H. Feist, “Zu einer Konzeption der Kunstwissenschaft in der DDR,” 5.

- [75] Badstübner, presentation, 236. On the GDR’s lack of a public sphere, see: Jürgen Habermas, “Dreißig Jahre Einheit: Die zweite Chance,” Blätter 9 (2020), 41–56.

- [76] See, for instance, the following published and unpublished works by Feist: “Das Problem des Einflusses in der Kunstgeschichte,” unpublished manuscript, September 22, 1957, GRI 940002, series 10, box 55, folder 2; “Die Dialektik in der Kunstgeschichte,” unpublished manuscript, August 1957, GRI 940002, series 10, box 55, folder 3; “Künstler und Gesellschaft” and “Motivkunde als kunstgeschichtliche Untersuchungsmethode,” in Künstler, Kunstwerk und Gesellschaft, 6–17 and 18–42; and “Neue Überlegungen zum Forschungsgegenstand ‘Kunstverhältnisse,’” in Akademie der Wissenschaften der DDR and Akademie der Künste der DDR, eds., Kunstverhältnisse: Ein Paradigma kunstwissenschaftlicher Forschung (Berlin: Institut für Ästhetik und Kunstwissen-schaften der Akademie der Wissenschaften der DDR, 1988), 12–19.

- [77] See, for instance, the contributions in: Friedrich Möbius, ed., Stil und Gesellschaft: Ein Problemaufriss (Dresden: VEB, 1984); as well as: Helga Möbius and Harald Olbrich, “Überlegungen zu einer sozialwissenschaftlichen Kunstgeschichte,” Bildende Kunst 1 (1982), Supplement 13, 1–16.

- [78] For an overview, see: Baier “…befreite Kunstwissenschaft,” 382–84.

- [79] Feist, Principles and Methods, 45–46.

- [80] “Nachruf von Horst Bredekamp,” in Feist, Hauptstraßen, 216.

- [81] Feist, “Einige Probleme des sozialistischen Menschenbildes,” 2.

- [82] Feist, Principles and Methods, 35.

- [83] See Tamara Golan, “‘Mit dem Kreidestift und Farben:’ Revolutionizing Grünewald in the German Democratic Republic,” Art History, vol.46, no. 2 (April 2023), 310–43.

- [84] “Kunstwissenschaft,” in Lexikon der Kunst, vol. 2, 816.

- [85] Ibid.

- [86] “Kunstgeschichte,” in Lexikon der Kunst, 786.

- [87] See: Badstübner, presentation, 237. For a comprehensive account of the term’s usage in the 1960s, see: Katja Bernhardt, “Kunstwissenschaft versus Kunstgeschichte: Die Geschichte der Kunstgeschichte in der DDR in den 1960er und 1970er Jahren als Forschungsgegenstand,” kunsttexte.de 4 (2015), 5–6; and on its prehistory, see: Katja Bernhardt, “Congenial Kunstwissenschaft: The Discussion on Art in the East German Zeitschrift für Kunst (1947–1950),” in Krista Kodres, Kristina Jõekalda, and Michaela Marek, eds., A Socialist Realist History? Writing Art History in the Post-War Decades (Cologne: Böhlau, 2019), 58–80.

- [88] Feist, Principles and Methods, 27.

- [89] Ibid., 30.

- [90] Ibid., 29.

- [91] On the Marxist discourse of art and aesthetics as “appropriation” (Aneignung), see: Thomas Metscher, “Kunst,” in Wolfgang Fritz Haug et al., eds., Historisch-Kritisches Wörterbuch des Marxismus, vol. 8, no. 1 (Hamburg: Argument, 2012), 468–69.

- [92] Feist, “Zu einer Konzeption der Kunstwissenschaft in der DDR,” 1. Similarly, see: Feist, “Einige Probleme des sozialistischen Menschenbildes,” 3.

- [93] Olbrich, presentation, 230.

- [94] One paradigmatic example is Cindy Persinger and Azar Rejaie, eds., Socially Engaged Art History and Beyond: Alternative Approaches to the Theory and Practice of Art History (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2021).

- [95] McKenzie Wark, Capital Is Dead: Is This Something Worse? (London: Verso, 2019), 143–64.

- [96] Feist, Principles and Methods, 48–50. On this striking imbalance, see also Nicos Hadjinicolaou’s essay in this special issue. On the potential influence of post-Stalinist Soviet scholarship on Feist’s “bourgeois” reading list, see: Krista Kodres, “Revisioning Stalinist Discourse of Art: Mikhail Liebman’s Academic Networks and his Social Art History,” Journal of Art Historiography 27 (2022), 1–16.

- [97] Feist, Principles and Methods, 50–51. For Warburg’s framing, see also “Kunstgeschichte,” Lexikon der Kunst, 789.

- [98] Feist, Principles and Methods, 33.

- [99] Cf. footnote 17.

- [100] For this globalist turn in Soviet art, see Douglas Gabriel’s essay in this special issue.

- [101] “Kunstwissenschaft,” Lexikon der Kunst, 816. On the impact of these discourses on Feist’s notion of cultural heritage, see: Antje Kempe, “Commentary on Feist’s Text,” in Antje Kempe, Beáta Hoch, and Marina Dmitrieva, eds., Universal – International – Global: Art Historiographies of Socialist Eastern Europe (Cologne: Böhlau, 2023), 113–17.

- [102] Feist, Principles and Methods, 35. For a more detailed account of his concept of influence, see his unpublished “Das Problem des Einflusses in der Kunstgeschichte.”

- [103] For Kubler’s criticism of biological metaphors, see: George Kubler, The Shape of Time: Remarks on the History of Things (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1962), 8–10.

- [104] Kerstin Schankweiler, “Brüche und Rupturen: Eine Postkoloniale Relektüre von George Kublers The Shape of Time,” in Sarah Maupeu, Kerstin Schankweiler, and Stefanie Stallschus, eds., Im Maschenwerk der Kunstgeschichte: Eine Revision von George Kublers “The Shape of Time” (Berlin: Kadmos, 2014), 127–45.

- [105] The foundational text in this regard is: Enrico Castelnuovo and Carlo Ginzburg, “Centro e periferia,” in Giovanni Previtali, ed., Storia dell’arte italiana, part 1, vol. 1 (Turin: Einaudi, 1979), 287–352.