Reimagining Lost Visual Archives of Black and Indigenous Resistance

How can we trace the wounds of colonialism in the art historical record? What forms do they take and how can we recognize them? In the eighteenth-century Atlantic world, the historical record holds many stories about the vibrancy of material and visual culture in forging an anticolonial consciousness. Black, Indigenous, and mixed-race artists created and circulated portraits, medallions, banners, prints, and talismans to galvanize support for coordinated uprisings that sought to dismantle the co-constitutive institutions of slavery and colonial rule. The Tupac Amaru Rebellion (1780-1783) of the southern Andes, the Haitian Revolution (1791-1804), and the Aponte Rebellion (1812) of Cuba, among countless other uprisings, are rife with accounts of artworks as critical intercessors in the creation of an anticolonial and radical abolitionist imaginary. Yet these stories arrive to us in battered, fragmented form, whether as ekphrastic descriptions in the scrawl of a notary furiously transcribing the courtroom confessions of the artist, or bare threads of a canvas whose pigments had been scraped away to excise the visage of a former rebel. The art histories of Black and Indigenous struggles for liberation are marked by profound and violent erasure; acts of imperial iconoclasm overseen by colonial officials functioned not only to silence insurgent counter-visualities but also to supplant them with absolutist imagery to reassert colonial control.

Given the precarious post-rebellion landscape, colonial officials prioritized the erasure of memory—borrar la memoria was a widespread trope in the archival and published documents surrounding anticolonial uprisings and slave rebellions in the Spanish Americas—which they attempted most notably through iconoclastic campaigns to destroy or efface offending images. State-sanctioned erasures, however, also produced their own material and performative excesses; the destruction of memory necessitated the widespread proliferation of cultures of surveillance in the eighteenth-century Atlantic world, a proliferation reflected in cartographic illustrations, portraits of the viceroy, and royal medals. I include these forms of visual culture within the rubric of what Nicholas Mirzoeff terms “surrogates of the sovereign,” which sought to maximize the gaze of the absent monarch through both the reproduction of his visage and the aesthetic performance of mastery over Andean landscapes that had otherwise been used to the tactical advantage of rebel forces deeply familiar with their contours.[1] The Spanish king’s absence from American soil required a robust apparatus of material surrogates that amplified his omnipresence, particularly in the aftermath of uprisings that threatened the future of colonial rule.[2] Surrogation was also a defining feature of the evangelizing imperative in early colonial Latin America; as Diana Taylor argues, the spread of localized Virgins within Mesoamerica produced deep anxieties on the part of friars whose writings centered on a recurring trope of whether Nahua deities had been effectively replaced or if they simply lived on in surrogate form.[3]

Yet surrogation, as Joseph Roach has amply demonstrated, can also serve as a strategy of cultural resiliency for recovering the voids and silences produced by colonization. His theorization of surrogacy offers a critical framework for interpreting performance and expressive culture in the circum-Atlantic world.[4] He posits that surrogation serves as an engine of social memory that fills “the cavities created by loss through death or other forms of departure.”[5] Other scholars such as David Lambert have extended Roach’s concept of surrogation to interpret commemorative statues in postcolonial Barbados.[6] Building on these formulations, I employ surrogacy as a strategy for cohering fractured object histories to magnify their historical presence in the eighteenth-century Atlantic world.

Can we thus use surrogacy to reimagine the transmission of liberatory aesthetics in the absence of an enduring corpus of surviving artworks? In advancing a decolonial approach to the deliberate fragmentation of the visual record of anticolonial and antislavery uprisings, an exploration of surrogate images can open up possibilities for reconstituting discontinuous temporal and geographical contexts of liberation movements across the Americas. From identifying contemporaneous approximations of now-lost early modern objects to considering contemporary reimaginings of historical figures who no longer survive in the artistic record, visual surrogates can help us write histories of art in contexts where the possibility of an intact material afterlife was foreclosed by colonial suppression. Assembling constellations of artists, artworks, and visual surrogates across multiple geographic and temporal contexts can make possible an otherwise inaccessible art historical narrative. This art history participates in a recuperative vision of the aesthetics of uprisings across the hemisphere, a vision that connects past and present in imagining alternative futures.

Erasure

A small eighteenth-century oil painting of the Our Lady of Mt. Carmel, spiritual protector of the rebel forces of the Tupac Amaru Rebellion, currently resides in the Church of Santa Catalina de Marcaconga in the Acomayo Province of Cuzco, Peru (Fig. 1). During the rebellion, each contingent had a religious patron who provided spiritual protection to their forces. The royalists frequently invoked St. Michael the Archangel and carried banners and paintings with his image—an appropriate choice given his close association with the military and spiritual conquest of the Americas.[7] The families comprising the rebel leadership in the southeastern provinces that incubated the rebellion in its early stages referenced Our Lady of Mt. Carmel in their correspondence and commissioned paintings of her for private and communal devotion.[8] In this painting, the top half features the Virgin bedecked in a rich floral shawl over her brown dress, held together by a jewel-encrusted broach. She holds the Christ Child in her left hand and the scapular in her right. Andean paintings of this Marian advocation frequently feature bodily souls in the bottom half of the composition receiving the brown scapular to be cleansed of their sins and escape purgatory. In fact, the eighteenth-century practice of painting portrait-like naked souls supplanted the earlier practice of rendering them as skulls and crossbones due to the dangers of associating skeletal remains with longstanding traditions of ancestor veneration.[9]

1. Virgen del Carmen, 18th century. Oil on canvas. Church of Marcaconga.

In other examples, such as in the well-documented painting of the Virgen del Carmen from the nearby Church of Yanaoca (a village near the natal towns of rebel leader José Gabriel Condorcanqui Tupac Amaru and that of his wife and co-conspirator, Micaela Bastidas), portraits of prominent Indigenous families congregate under her mantle (Figs. 2, 3). The iconography shares striking similarities with Renaissance paintings of the Madonna della Misericordia (Our Lady of Mercy), which feature large groups of the faithful protected by her expansive cloak; the most iconic example pertaining to the colonial enterprise is perhaps Alejo Fernández’s Virgen de los Navegantes (1531-36) at the Casa de la Contratación in Seville, Spain.[10] According to descendant Juan de la Cruz Salas, the individuals in the Yanaoca canvas represented members of the Condorcanqui and Tito Condemayta family who constituted the core of rebel leadership, including none other than portraits of Tupac Amaru and his wife and co-conspirator Micaela Bastidas immediately flanking the Virgin.[11] Recent restorations reveal that their portraits had been covered up in the nineteenth century and transformed into a priest and brigadier whose uniform resembles those of Independence leaders like Simón Bolívar and José de San Martín.[12] The post-restoration photograph of the painting reveals the purported portrait of Tupac Amaru to the left of the Virgin, while Micaela ostensibly still remains hidden beneath the guise of the priest. Further investigation of the details of the restoration are unfortunately not possible, however, because the painting’s current whereabouts remain unknown.

2 (left). Pre-restoration image of the Virgen del Carmen with donors, 18th century. Church of Yanaoca. Whereabouts unknown.

3 (right). Post-restoration image of the Virgen del Carmen with donors, 18th century. Church of Yanaoca. Whereabouts unknown.

Yet in the Marcaconga painting, the area that would have been occupied by donor portraits or naked souls in purgatory is instead marked by a material void; the paint has been scraped down to the canvas fibers, and a gaping hole takes up the bottom quarter of the composition. The entire image is circumscribed by a blue and white roundel, and it is notable that nearly the entirety of the white painted frame circumscribing the Virgin and Child remains intact. Furthermore, the most important elements of the composition—the Virgin’s face and torso and the Christ Child—are free of blemishes, all of which suggests a targeted and strategic defacement below. The timing of the defacement, which I propose occurred in the post-rebellion era, is further corroborated by the historical record of the village of Marcaconga. Pedro Agustín de Cabrera y Yepes served as priest of Sangarará, of which Marcaconga is an annex, in 1796. Despite the fifteen-year interval between the rebellion and the beginning of his service, he noted the damage sustained by the Church of Sangarará and others in his district from the Tupac Amaru Rebellion. Among his notable achievements recorded in his relación de méritos included his active patronage and self-financing of repairs to churches that had been ransacked or destroyed by rebel forces. This included arranging for the construction of a new retablo mayor for the Church of Sangarará as well as paintings for the churches of Marcaconga, Yanampampa, and Acopia.[13]

Can we also include the cutting away of the canvas as part of Cabrera’s post-rebellion initiative? It is a likely possibility if the portrait featured the visage of any individual who was complicit in the rebellion, given that there are frequent references in inventories and account books from the period of paintings and sculptures being retouched (retocado) or refurbished (reacondicionado) after the rebellion. In fact, there is even a reference to changing the faces of various images at the Church of Vilque between 1781 and 1783 (“se cambiaron rostros de varias imágenes”). Given the timing of the repairs, this phrase may have concerned the pictorial editorializing of portraits of individuals who may have been complicit in the rebellion.[14] Such practices would have been in line with a decree issued by Royal Inspector José Antonio de Areche in 1781 that prohibited the representation of Incas and their descendants, along with a litany of other types of artwork and cultural expressions retroactively deemed subversive for their supposed role in inciting rebellious behavior.[15] Cabrera may have called for the removal of the donors or souls in purgatory beneath the Virgen del Carmen with the expectation of repairing the canvas with a more “decent” image, especially given the elevated suspicion around representations of this Marian advocation during the period of insurgency. For example, in the proceedings against Juan Bautista Tupac Amaru, half-brother of José Gabriel Condorcanqui, he is presented with two small paintings that had been in his possession: one of the coat of arms of the King and the other a painting of the Virgen del Carmen. The latter was under particular scrutiny due to its “suspect appearance” [apariencia de sospecha], although it was ultimately decided that it was poorly painted—itself a violation of the Holy Office of the Inquisition.[16]

The material unraveling of the painting, from scraping off the paint to cutting away the canvas, destroyed the visage of any figure that would have been depicted beneath. This dramatic act of effacement not only succeeded in erasing the representation of the souls or donors that would have been depicted in the painting, but it also foreclosed the possibility of their redemption and ascension to Heaven. This act of erasure now operates on multiple levels: on the one hand, it has removed the figures within the painting that indexed actual individuals who may have lived and died in this community; on the other, paintings like these rarely receive careful art historical analysis due to the extensive damage sustained in such a central part of the canvas. Yet the painting carries a certain poetics in its dematerialized state; presumably a low-priority artwork for contemporary restoration, it proclaims loudly the methodology of its erasure and thus opens the possibility for more nuanced analysis of the circumstances that shaped its current appearance.

Loss

Documentary accounts of the Tupac Amaru and Tupac Katari rebellions describe pictorial representations of the rebel leaders that took the form of large-scale painted portraits, prints, and flags. The painted portraits have received the lion’s share of scholarly attention for the significant detail with which they are described in the court proceedings that took place after the capture of Tupac Amaru. Less attention has been placed, understandably so, on smaller-scale representations that receive only passing mention in the documentary record. Witnesses described large wooden medallions bearing the visage of Tupac Amaru and his wife and co-conspirator Micaela Bastidas that were worn around the necks of their supporters. The use of wood here suggests a connection to technologies of reproduction, especially in light of the reference to the “copy” in the account: “and some large wooden medallions with the copy of the figures of him, and his wife [Tupac Amaru and Micaela Bastidas].”[17] Perhaps these medallions also served as woodblocks for the rapid transmission of their image on paper? The humble materials from which they were made also speaks to the ad-hoc, improvisational nature of artistic production during the era of the rebellion, in which artists produced small-scale representations of the leaders using cheap and widely available materials.

4. Silver medal with Charles III on the obverse and “Al Mérito y Fidelidad” on the reverse, 1806. American Numismatic Society, accession no. 1921.135.1.

It would not be until the post-rebellion era that we see the widespread production of silver medallas de paz issued by the King of Spainthat would have been minted in the city of Potosí, which were gifted to loyal Indigenous leaders who supported the royalist cause. These medals resembled contemporaneous coinage, with a profile portrait of King Charles III on one side and the words “en premio de la fidelidad” or “al mérito” stamped on the reverse (Fig. 4). The proliferation of medallas de paz in the post-rebellion era thus reasserted royal oversight through complex ceremonial rituals in which caciques proclaimed their loyalty to the King as they were draped with the medals bearing the monarch’s face in the plaza while facing the royal portrait.[18] These enduring emblems of the colonial enterprise survive in great quantities in numismatic collections across Latin America, Europe, and the United States. Their creation thus simultaneously functioned as an act of erasure through the extreme replication of the gaze of the sovereign in durable, value-laden materials, while also effectively supplanting the wooden medallions that survive only as passing description from the trial transcriptions.

As objects to be worn on the body, medallions bound their wearers in an intimate relationship with the imagery and the broader messages that they encoded. Medallions took on a variety of forms in the early modern world, from religious medallions that indexed the devotee’s connection to local cults to medallions marking a coveted social or political status. For example, in Alto Perú, Diego de Ocaña’s image of the Virgin of Guadalupe in Sucre circulated in the form of both prints and medallions. These copies were activated through the practice of touching them to the cult statue, as Astrid Windus explains, “to ‘capture’ and preserve the miracle-working powers of the original image.”[19] Members of the Indigenous elite commissioned portraits that boasted pectorals with sunbursts or medallions of the Virgin in their sartorial self-fashioning. Yet no known examples survive of the wooden medallions of the rebel leaders and the documentation remains thin on the specificities of their facture.

How might the visual record of Atlantic abolitionist and freedom struggles shed further light on these medallions that have been lost to history? While a logical site for reimagining the appearance of the wooden medallions may be to consider Bolivarian imagery of South American Independence movements of the 1820s, I suggest that a more productive site for thinking through an aesthetics of grassroots insurgency is the Haitian Revolution (1791-1804) and the groundswell of slave rebellions that occurred contiguously across the Atlantic world. News of Black and Indigenous uprisings traveled quickly across the Americas and the Caribbean, both through official channels as well as more popular, vernacular channels in the form of pasquinades, broadsides, and books, and oral transmission.[20] The movement of revolutionary visual and material culture has been far less explored, but these items may have traveled alongside and within print culture networks; pasquinades were often illustrated, and some printed books about the Haitian revolution that circulated in the early nineteenth century contained images. Further, small-scale objects such as fans, playing cards, and prints could have supplied iconography that would inform the production of objects of anticolonial resistance.

To take one example, historian João José Reis discovered references to necklaces with the image of Jean-Jacques Dessalines that were worn by Afro-Brazilians who led a slave rebellion in Rio de Janeiro in 1805, just one year after Haiti had declared itself an independent Black Republic.[21] Imagery of the first ruler of independent Haiti appears in the widely circulated books La vie de Jean-Jacques Dessalines (Paris, 1804) and A Historical Account of the Black Empire of Hayti (London, 1805), both of which may have traveled to the Brazilian port city within a year of their publication. As the most widely disseminated images of the Haitian leader in the years immediately following the Revolution, these prints most likely would have served as templates for the creation of the necklaces. Dessalines’ negative textual characterization in these books, described by M. Dubroca as “cowardly,” “cruel,” “extremely violent,” and “extremely ignorant,” matches the portraits of him and other leaders of the Haitian Revolution contained therein, likewise bound up in pervasive tropes of Black barbarism.[22] Mia Bagneris’s discussion of the apocryphal buttons of Toussaint Louverture’s coat decorated in imagery by the Italian émigré artist Agostino Brunias is particularly apt here. Despite the unlikelihood of the buttons’ actually belonging to Louverture, the broader takeaway is that images like that of Brunias that are grounded in “a pro-slavery, colonialist agenda,” as she contends, demonstrate “the potential of the images to be repurposed to serve interests contrary to those that they were originally intended to reflect.”[23] The recasting of colonialist imagery in the hands of Afro-Brazilian rebels similarly speaks to the interpretive flexibility of images in periods of social conflict when categories of artist, patron, and artwork became unfixed and resulted in the emergence of new forms of visuality and countervisuality.[24] Moreover, it also highlights the world-making capacities of insurgents to radically recontextualize dehumanizing imagery into talismanic objects that reroute the flow of power in support of liberation projects.

5. Jean Fouquet and Gilles-Louis Chrétien, Medallion Portrait of Vincent Ogé. Hand-colored engraving, Paris, 1790. Winterthur Museum, Winterthur, Delaware. Museum purchase with funds provided by the Henry Francis du Pont Collectors Circle. Object number 2017.0013.001.

A colored print that served as the template for a medallion housed at the Winterthur Museum may offer some visual clues for the lost Tupac Amaru medallions and Dessalines necklaces (Fig. 5). Vincent Ogé, a free man of color from the northern Haitian town of Dondon, was in Paris in 1789 when the French Revolution broke out. He advocated for the full recognition of free men of color under the terms of the Declaration of the Rights of Man, a demand met with staunch disapproval by French authorities. Upon his return to St. Domingue in October of 1790, he led a rebellion against white planters, with the support of hundreds of mixed-race compatriots. The rebellion was swiftly defeated, leading to the brutal execution of Ogé and his supporters in February of 1791.[25] As the text below the roundel indicates, the image was drawn by the French artist Jean Fouquet and engraved by Gilles-Louis Chrétien. Its formal similarities to other profile portraits created by Chrétien suggest that the method for producing this image was the pre-photographic technique of physionotrace.[26] The print’s 1790 date and production in France tells us that Ogé may have commissioned this image to garner support for his cause. The caption beneath his bust reads “il aime la liberté comme il sait la deffendre,” or “he loves freedom as he knows how to defend it,” providing a stark counterpoint to contemporaneous Spanish colonial medallas de paz that proclaim loyalty to the king in the stamped text and through the ceremonies by which the medals were distributed.

While Ogé’s image was itself an unfinished project, we might assume that this print served as the prototype for actual medallions that could have been distributed to supporters either in Paris or in St. Domingue. The portrait thus opens up a space for imagining how the Tupac Amaru and Dessalines medallions and necklaces may have looked. These visual connections that would put Peru and Haiti into conversation are less far-fetched than they may appear. As Sinclair Thomson has demonstrated, news of the Tupac Amaru Rebellion arrived on St. Domingue’s shores by 1781.[27] Dessalines referred to his soldiers as the “army of the Incas,” a name which may have been influenced both by news of the Andean uprising as well as through circulation of Voltaire’s Alzire (1736), which was staged in the cities of Le Cap and Port-au-Prince in 1783, replete with Inca-style costumes.[28] The Ogé surrogate, itself engaged in a transatlantic discourse of the meanings of freedom articulated by those who fall beyond the bounds of empire’s definitions of full personhood, grants visual and material form to other works forged under similar conditions that survive only as brief, passing textual references.

Reimagining

Just as the Ogé print can serve as a contemporaneous surrogate for lost images of the Tupac Amaru Rebellion and Haitian Revolution, I turn now to the work of contemporary artists whose artistic surrogates serve as a mode of reckoning with art histories marked by distortion and erasure. For the 2018 exhibition “Visionary Aponte: Art and Black Freedom,” curators Edouard Duval-Carrié, Ada Ferrer, Laurent Dubois, Tosha Grantham, and Linda Rodriguez invited fourteen Caribbean, Caribbean diasporic, and Latinx artists to create pieces that reimagine an extraordinary work of art by José Antonio Aponte, a free Black carpenter and former soldier who was the architect of a slave rebellion in Cuba in 1812.[29] Central to its planning and execution was his enigmatic libro de pinturas (book of paintings), which he kept carefully guarded in his home and showed to his co-conspirators.

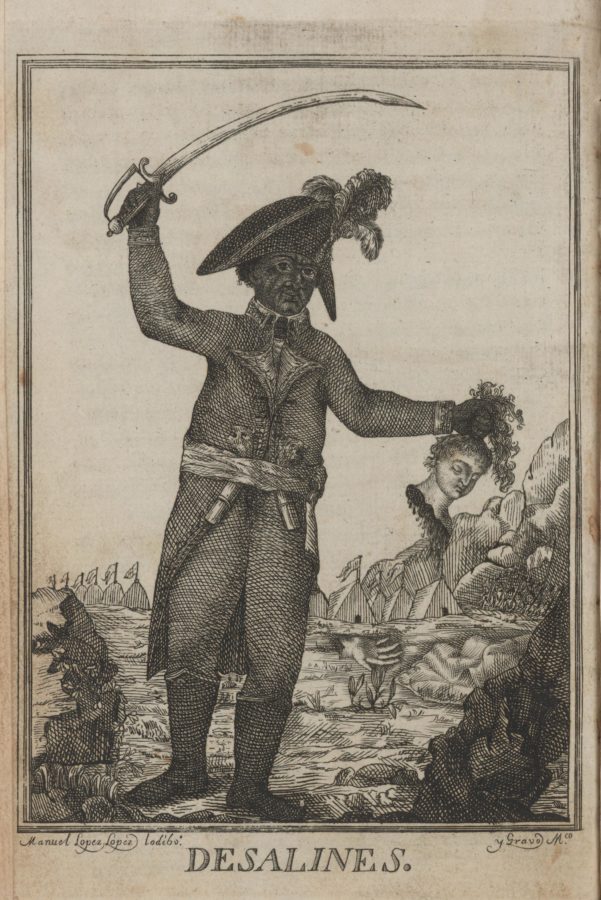

6. Manuel López López, etching of “Desalines” [sic] in M. Dubroca, Vida de J. J. Dessalines: Gefe de los negros de Santo Domingo; con notas muy circunstanciadas sobre el origen, carácter y atrocidades de aquellos rebeldes desde el principio de la insurreción en 1791…, edited by Juan López Cancelada (Mexico City, 1806); Spanish translation of La vie de Jean-Jacques Dessalines… (Paris, 1804).

Attentive to the tremendous political import of visual culture in fomenting revolution, Aponte’s book of pictures featured sixty-three images of Black sovereignty and liberation that relied on an extensive repertoire of biblical, popular, and scholarly sources ranging from portraits of the heroes of the Haitian Revolution to Ethiopian kings that came from books, loose-leaf prints, and even fans.[30] The book also included battle scenes of Black soldiers holding the decapitated heads of white men, likely inspired by iconic imagery that came out of the Haitian Revolution; take for example the engraving of Jean-Jacques Dessalines included in the aforementioned La vie de Jean-Jacques Dessalines, which could have reached Cuba’s shores via a translated copy published in Mexico as a special supplement to the Gaceta de Mexico, with numerous illustrations designed and engraved by local artist Manuel López López in 1806 (Fig. 6).[31] The images in Aponte’s book were to serve as tactical blueprints for the insurrection that occurred on the Peñas Altas plantation. When Aponte was captured by colonial authorities, he was forced to provide painstaking descriptions of the book, which has remained “lost” since his public execution on April 9, 1812. These descriptions survive as transcriptions of trial testimony, which scholars have used as a key resource in tracking the sources and possible imagery that Aponte included in his mixed-media codex of collaged prints and drawings.[32]

7. Marielle Plaisir, The Book of Life, 2017, folio 8. Ink, pencil, and glitter on paper. 15 x 20 in.

I focus here on French-Caribbean multimedia artist Marielle Plaisir’s contribution to Visionary Aponte, a series of over fifty watercolor paintings that together comprise The book of life (2017), because of its relative fidelity to the original format of Aponte’s codex as a compendium of images on paper that create a narrative about Black freedom. As the curators state, her watercolors “do not depict particular pages of Aponte’s book. Rather, they evoke the way Aponte escapes from the world by deconstructing his time and place, moving through mythology, religion, death, war, love. For Plaisir, Aponte’s ‘Book of Paintings’ represents a kind of beautiful exile, his process of dreaming about a better world.”[33] Each page of her book is organized compositionally around blotches of paint that spread organically across the paper, upon and around which she layers additional pigments and line drawings. Some of her compositions can be read like ink blots, such as in folio 8, suggesting an incommensurability between the written word and the story that she has set out to tell (Fig. 7). These stains on the page simultaneously evoke a faulty quill or words that have been intentionally blotted out; but it is from these stains on the page that Plaisir fashions her otherworldly compositions of mythic creatures, skeletons, plants, and bugs festooned with strands of pearls and other bead-like patterns.

8 (left). Marielle Plaisir, The Book of Life, 2017, folio 6. Ink, pencil, and glitter on paper. 15 x 20 in.

9 (right). Marielle Plaisir, The Book of Life, 2017, folio 56. Ink, pencil, and glitter on paper. 15 x 20 in.

In folio 6, black ink stains are transformed into what looks like a glittering night sky that encircles the visage of an individual dressed in seventeenth-century clothing, replete with a ruff collar and a feathered cap, reminiscent of Dutch Golden Age portraits (Fig. 8). Plaisir has left the body and hat of the sitter in black and white but painted the face with a wash of dark brown pigment. The face is devoid of features but the color marks him as a Black dignitary—an extreme rarity in early modern European portraiture. Plaisir’s faceless but racially-marked portrait alludes to the images of leaders of the Haitian Revolution and Ethiopian kings and queens that Aponte included in his book. We find a similar composition in folio 56 of a royal sitter wearing a ruff collar and elaborate shirt decorated with fleurs de lis (Fig. 9). We can also read Plaisir’s portraits as limned images, or prefabricated paintings with everything completed but the face, which the artist would fill in when he traveled to view the likeness of the sitter.

The blank faces open a space for inserting any number of Black revolutionary figures into the frame; she creates the possibility in the twenty-first century of what was nearly inconceivable in the seventeenth, when Black figures frequently occupied the corners and shadowy spaces of early modern European paintings as foils against which to view the rarified whiteness and wealth of their patrons.[34] By rendering the faces devoid of specific features that would tie them to a specific individual, Plaisir gestures to the dearth of actual likenesses of Black revolutionary figures from the Age of Revolutions, from Aponte to Louverture; most surviving representations were produced posthumously and were continually recast and reinvented by each successive generation.[35] Plaisir engages in a nuanced form of radical reimagining of lost objects of insurgent resistance through her pictorial reinterpretations of Aponte’s anguished courtroom confessions, while still obscuring the actual likenesses of the figures to signal that full recovery can never be possible. Perhaps the blank faces in the folios of Plaisir’s Book of life also enable infinite reimaginings of the historical figures that animated Aponte’s dreams of a better world.

10. Firelei Báez, For Améthyste and Athénaire (Exiled Muses Beyond Jean Luc Nancy’s Canon), Anaconas. Museum of Modern Art Modern Windows Series, 2018.

It was in this same impulse of radical visioning of Afro-Caribbean historical figures whose visages evade the visual record that Firelei Báez produced For Améthyste and Athénaire (Exiled Muses Beyond Jean Luc Nancy’s Canon), Anaconas for the Museum of Modern Art’s Modern Window Series in 2018 (Fig. 10). Báez, an Afro-Dominican American artist, has long explored themes of exile, displacement, race, and memory in her work.[36] Baez’s recent immersion in historical African American and Caribbean archives, facilitated by her residency at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in 2018, resulted in her exhibition Firelei Báez: Joy Out of Fire, an InHarlem project that was a partnership between the Studio Museum in Harlem and the Schomburg Center.[37] Her piece For Améthyste and Athénaïre opened four months later. This large-scaled painted installation features portraits of the daughters of Henri Christophe, the first king of Haiti, who were exiled to Italy after his death in 1820. The installation responds directly to Báez’s query and provocation: “how do you make someone present when history has made such an effort to erase them?”[38] For Améthyste and Athénaïre emerges from the double silencing of Black women from the Caribbean visual archive, another painted surrogate that stands in for the plethora of images that never were, never could have been, or have otherwise been lost to history for reasons that are far from innocent or incidental.

The work consists of two portraits of the sisters, rendered in purple, red, and brown tones. They wear red headdresses, whose appearance and color evoke distinct yet intertwined colonial histories of the Americas. The bold red of the headdresses, as Báez notes, references cochineal, which in turn points to Indigenous labor and various technologies of Mesoamerica. This substance journeyed the world as one of the most prized and coveted pigments, quickly denuded of its original associations with Nahua place-based knowledge and aesthetics.[39] The blue and purplish color of their bodies and the walls, Báez tells us, references indigo, a pigment intimately tied to West African botanical knowledge that was exploited in the cultivation of St. Domingue’s cash crop. The portraits are delimited with sumptuous white frames and decorative appliques that, while conjuring nineteenth-century French décor, upon closer inspection reveal connections to Vodou and West African spirituality.[40]

11. Jacques Guillaume Lucien Amans, Creole in a Red Headdress, circa 1840. Oil on canvas. The Historic New Orleans Collection, 2010.0306.

Similarly to the blank faces of Plaisir’s portraits, Báez’s figures are devoid of facial features except for eyes that gaze pointedly at the viewer. Báez has granted Améthyste and Athénaïre “the right to look,” or imperial visuality’s counterpoint.[41] Yet even as these portraits are intended to reimagine figures who have been erased from history, it is evident that elements of the paintings were inspired by eighteenth and nineteenth-century visual models like Marie-Guillemine Benoist’s Portrait of Madeleine (formerly Portrait of a Negress) (1800) and Jacques Guillaume Lucien Amans Creole in a Red Headdress (ca. 1840) (Fig. 11). By engaging with textual, visual, and material archives of the Black Atlantic in the creation of this piece, Báez practices a form of visual reckoning.[42] She reanimates Afro-Caribbean historical figures who were erased from the visual record and creates them anew using some of the same colors and aesthetic conventions that were born out of the early modern Atlantic world, but deliberately disrupts the very flow of power that trafficked in the capture and control of Indigenous and Black people’s labor and expertise to produce the cochineal and indigo. In so doing, Báez also disrupts the representational system, grounded in that trafficking’s epistemic violence, that denied personhood to the very subjects who produced the material possibilities for its existence. Báez, as an Afro-Dominican artist, produces a critical counterpoint to the circular logics of coloniality and repairs the violations of consent that often occurred when Black women sat before the easels of white artists in the eighteenth century.[43]

Recovery

Luckily, the losses that inspired the creation of works like For Améthyste and Athénaire are not always permanent. At almost precisely the same time that Baez unveiled her piece at MoMA, an oil painting by an unknown artist depicting Jacques-Victor Henry (King Christophe’s son), Anne-Athénaïre, and Françoise-Améthyste dating between 1811-1820 resurfaced at an auction house in New York City (Fig. 12). The painting features Christophe’s son with one hand tucked into his overcoat as his sisters stand beside him, one lovingly touching his shoulder, as all three look directly at the viewer. The sisters wear translucent gowns, pearls around their neck, and simple jeweled barrettes and headbands. After a long series of negotiations with the Haitian government, the painting was re-homed in October of 2020, and currently resides at the National Museum of Haiti in Port-au-Prince (MUPANAH).

12. Unknown artist, Portrait of Jacques-Victor Henry, Anne-Athénaïre, and Françoise-Améthyste, circa 1811-1820. Musée du Panthéon National, Haiti.

Báez’s work suddenly takes on a different cast; with the recovery of the portrait, how do we now approach For Améthyste and Athénaire? And in turn, how can For Améthyste and Athénaire inform the way we approach the historical triple portrait of Roi Christophe’s children? In her engagement with archives and materialities of the eighteenth and nineteenth-century Atlantic world, Báez’s work enables us to see overlooked subjectivities obscured even in rare surviving paintings such as the triple portrait. Her pointed use of blue and red to unpack the legacies of Black and Indigenous ecological and aesthetic place-based knowledge as well as her integration of West African and Afro-Caribbean symbolism in the ornate architectural molding bring to the foreground the debt that the Enlightenment plays to the creative ingenuity of enslaved and exploited laborers. While the sisters are squeezed together to make compositional space for Jacques-Victor Henry in the nineteenth-century portrait, in Firelei Báez’s reimagining, they not only are accorded their own space, but even spill out of their respective frames, their presence too large to be contained.

Erica Moiah James argues that Haitian art of the nineteenth century in the years immediately following the Haitian Revolution has been consistently derided as anachronic, second-rate, and derivative—characterizations that have also deeply marked the historiography of colonial Latin American art and have thus made it impossible for these works to be truly seen.[44] She states, “I argue that to see nineteenth-century Haitian portraits requires a rethinking of notions of time, space, and development reaffirmed through Western art-historical methodologies…. It also necessitates the disaggregation of colonial implications of time as evidence of value that are embedded in critiques of anachronism that persist.”[45] The triple portrait’s conformity to European visual conventions—the characteristics that would condemn it as anachronistic or derivative—is also likely what ensured its survival.[46] By eschewing colonial regimes of time and periodization, James demonstrates how portraits like this one relied upon creolized articulations of European compositional and stylistic conventions as a means for Haitian sovereigns to assert their power on the world stage. Taking James’ lead, when freed from the constraints of linear timelines, contemporary works like that of Báez and Plaisir can also articulate what Ariella Aïsha Azoulay refers to as “potential history,” which “strives to retrieve, reconstruct, and give an account of diverse worlds that persist despite the historicized limits of our world.”[47] For Améthyste and Athénaire adds another layer of depth to the permutations of erasure, loss, reimagining, and recovery that punctuate our story. The nineteenth-century portrait and Baez’s twenty-first century work draw on drastically different modes of representation; as may be expected, they look nothing alike. But when they are placed into a broader hemispheric framework of insurgent images and their afterlives, we soon see the profound interdependence of these artworks and the histories that foreground them. The deliberate erasure of objects of anticolonial and abolitionist resistance from the art historical record, whether through excision, destruction, or confiscation, meet their afterlives in other media, across time and oceans. Through a generous reading of the art historical record that relies on contingency and surrogacy as a methodology of repair, we can begin to catch a glimpse of an aesthetics of liberation that shines through despite a deliberately truncated visual archive.[48]

I am grateful to Jennifer Nelson for inviting me to participate in this issue. Her insightful comments, as well as those of the anonymous reviewer, provided wonderful food for thought in the editing process. I also extend deep gratitude to Faye Gleisser, Emmanuel Ortega, and Erin Reitz for their valuable feedback on an earlier draft of this article. Finally, I presented an earlier version of this paper at the Digital Seminar on Race, Coloniality, and Global Art Histories convened by Bart Pushaw and Mathias Danbolt of the University of Copenhagen, and am appreciative of the constructive comments and suggestions offered by the participants.

- [1] Nicholas Mirzoeff, The Right to Look: A Counterhistory of Visuality (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011), 2–3.

- [2] For further discussion, see Alejandra B. Osorio, Inventing Lima: Baroque Modernity in Peru’s South Sea Metropolis (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008), 81–102; Alejandro Cañeque, “Imaging the Spanish Empire: The Visual Construction of Imperial Authority in Habsburg New Spain,” Colonial Latin American Review, vol. 19, no. 1 (2010), 29–68; and Emily A. Engel, “Changing Faces: Royal Portraiture and the Manipulation of Colonial Bodies in the Viceroyalty of Peru,” in Ilenia Colón Mendoza and Margaret Ann Zaho, eds., Spanish Royal Patronage, 1412-1804: Portraits as Propaganda, (Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2018), 149–69.

- [3] Diana Taylor, “DNA of Performance: Political Hauntology,” in Cultural Agency in the Americas, ed. Doris Sommer (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2006), 60–61.

- [4] Joseph Roach, Cities of the Dead: Circum-Atlantic Performance (New York: Columbia University Press, 1996), 1–7.

- [5] Ibid., 2.

- [6] David Lambert, “‘Part of the Blood and Dream’: Surrogation, Memory and the National Hero in the Postcolonial Caribbean,” Patterns of Prejudice, vol. 41, no. 3–4 (2007), 345–71.

- [7] Luis Durand Florez, ed., Colección documental del bicentenario de la revolución emancipadora de Tupac Amaru, vol. 1 (Lima: Comisión Nacional del Bicentenario de la Rebelión Emancipadora de Tupac Amaru, 1980), 145; Marie-Danielle Demélas, La invención política: Bolivia, Ecuador, Perú en el siglo XIX (Lima: IFEA, Instituto Francés de Estudios Andinos, 2003), 83.

- [8] Isidro Salzman, “La insurrección de Túpac Amaru y la literatura argentina,” Todo es historia 151 (1979), 57.

- [9] Maya Stanfield-Mazzi, “El complemento artístico a las misas para difuntos en el Perú colonial,” Allpanchis 77/78 (2014), 49–81.

- [10] For a digital image of the entire altarpiece, see https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Retablo _virgen_mareantes_1_Alcazar_Seville_Spain.jpg.

- [11] Alfonsina Barrionuevo, “El verdadero rostro de Túpaq Amaru,” Caretas, 1972; José de Mesa and Teresa Gisbert, Historia de la pintura cuzqueña, vol. 1 (Lima: Fundación Banco Wiese, 1982), 285.

- [12] Teresa Gisbert, Iconografía y mitos indígenas en el arte, 5th ed. (La Paz: Biblioteca del Bicentenario de Bolivia, 2018), 315–16.

- [13] Graciela María Viñuales and Ramón Gutiérrez, Historia de los pueblos de indios de Cusco y Apurímac (Lima: Universidad de Lima, 2014), 492.

- [14] Viñuales and Gutiérrez, 373. While “imagen” in these documents can refer to either a sculpture or a painting, given the context of the statement, it seems to refer to the latter in this case.

- [15] Juan Carlos Estenssoro, “La plástica colonial y sus relaciones con la gran rebelión,” Revista Andina, vol. 9, no. 2 (1991), 415–39; David Cahill, “El Visitador General Areche y su campaña iconoclasta contra la cultura andina,” in Ramón Mujica Pinilla, ed., Visión y Símbolos: del virreinato criollo a la República Peruana, (Lima: Banco de Crédito del Perú, 2006), 83–111.

- [16] Juan Bautista Túpac Amaru, Cuarenta años de cautiverio: memorias del Inka Juan Bautista Túpac Amaru, ed. Francisco A. Loayza (Lima: Librería e Imprenta D. Miranda, 1941), 97–98. In Inquisition trials that took place across the Spanish empire, artworks were targeted for sexual content and inappropriate inclusion or exclusion of religious figures; for example, a sixteenth-century painting of the Last Judgment was under scrutiny by the Office of the Inquisition in Lima (also described as “mal pintado”) for excluding representations of Christ and the twelve apostles. See José Toribio Medina, Historia del Tribunal de la Inquisición de Lima, 1569-1820 (Santiago de Chile: Imprenta Gutenberg, 1887), 311–12.

- [17] The full account reads as follows: “…sus vesinos Españoles e Yndios fieles condujeron mas de veinte y tantos Yndios Reveldes, a quienes se les quitaron barios papeles de combocatoria y Autos de Tupac Amaro, y unas medallas grandes de madera con la copia de las figuras de este, y su muger, con cuia ensignia se aberiguo asian las combocatorias por lo que fueron ajusticiados, y prontamente se prosigió la marcha para el mencionado Pueblo de Moza, y entrado el con sola una compania, dejando el Batallon a distancia de quatro de legua sintieron aquellos sus avistadores grande alivio de la oprecion que padesian.” Archivo Nacional de Bolivia, Sublevaciones de Indios 100, fol. 5r.

- [18] Eugenia Bridikhina, Theatrum mundi: entramados del poder en Charcas colonial (La Paz: Plural Editores, 2007), 237.

- [19] Astrid Windus, “‘Y yo, con buen celo y ánimo, tomé los pinceles del oleo …’: Dynamics of Cultural Entanglement and Transculturation in Diego de Ocaña’s Virgin of Guadalupe (Bolivia, 17th–18th Centuries),” Colonial Latin American Review, vol. 27, no. 4 (2018), 446.

- [20] Cristina Soriano, Tides of Revolution: Information, Insurgencies, and the Crisis of Colonial Rule in Venezuela (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2018), 47–75.

- [21] João José Reis, Slave Rebellion in Brazil: The Muslim Uprising of 1835 in Bahia, trans. Arthur Brakel (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1993), 48.

- [22] M. Dubroca, Vida de J. J. Dessalines: Gefe de los negros de Santo Domingo; con notas muy circunstanciadas sobre el origen, carácter y atrocidades de aquellos rebeldes desde el principio de la insurreción en 1791…, ed. Juan López Cancelada (Mexico City, 1806), 70–71.

- [23] Mia L. Bagneris, Colouring the Caribbean: Race and the Art of Agostino Brunias (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2018), 230.

- [24] Ananda Cohen-Aponte, “Art-Making and Art-Breaking in the Era of Andean Insurgencies,” in Maya Stanfield-Mazzi and Margarita Vargas-Betancourt, eds., Beyond Biography: Being an Artist in Colonial Latin America (Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida, forthcoming, 2022).

- [25] John D. Garrigus, “Vincent Ogé ‘Jeune’ (1757-91): Social Class and Free Colored Mobilization on the Eve of the Haitian Revolution,” The Americas, vol. 68, no. 1 (2011), 33–62.

- [26] Gabriele Chiesa and Gianpaolo Gosio, Dagherrotipia, ambrotipia, ferrotipia positivi unici e processi antichi nel ritratto fotografico (Italy: Youcanprint, 2012), 19.

- [27] Sinclair Thomson, “Sovereignty Disavowed: The Tupac Amaru Revolution in the Atlantic World,” Atlantic Studies, vol. 13, no. 3 (2016), 415.

- [28] Ibid., 426; ff36.

- [29] The exhibition debuted at the Little Haiti Cultural Center in Miami and then traveled to the King Juan Carlos I of Spain Center at NYU, followed by Duke University. “Visionary Aponte: Art & Black Freedom,” exhibition pamphlet, n.p. For a discussion and reflection on Visionary Aponte, see Linda M. Rodriguez and Ada Ferrer, “Collaborating with Aponte: Digital Humanities, Art, and the Archive,” Sx Archipelagos 3 (2019), 1–16.

- [30] For more on Aponte’s book of paintings, see Linda M. Rodriguez, “Artistic Production, Race, and History in Colonial Cuba, 1762-1840” (Ph.D Dissertation, Harvard University, 2012); and Jorge Pavez Ojeda, “The ‘Painting’ of Black History: The Afro-Cuban Codex of José Antonio Aponte (Havana, Cuba, 1812),” in Adrien Delmas and Nigel Penn, eds.,Written Culture in a Colonial Context: Africa and the Americas, 1500-1900 (Leiden: Brill, 2012), 283–315.

- [31] Kelly Donahue-Wallace, “Abused and Battered: Printed Images and the Female Body in Viceregal New Spain,” in Kellen Kee McIntyre and Richard E. Phillips, eds., Woman and Art in Early Modern Latin America (Leiden: Brill, 2006), 138–39.

- [32] Pavez Ojeda, “The ‘Painting’ of Black History,” 286–87.

- [33] “Visionary Aponte: Art & Black Freedom,” exhibition pamphlet, n.p.

- [34] Gwendolyn DuBois Shaw, Portraits of a People: Picturing African Americans in the Nineteenth Century (Andover, MA: Addison Gallery of American Art, Phillips Academy, 2006); David Bindman and Henry Louis Gates Jr., The Image of the Black in Western Art: From the “Age of Discovery” to the Age of Abolition: Artists of the Renaissance and Baroque (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2010).

- [35] As Anthony Bogues notes with respect to Duval-Carrié’s representations of Touissant Louverture, “During Toussaint’s life, there were numerous images made of him, but what did the real Toussaint look like? In such a context, a historical figure takes on a new imaginary. He becomes representative of the nation or the event at its most pristine. Each generation of artists produces a new Toussaint, creating the ground for art and history to mix in the creation of an alchemy of images.” Anthony Bogues, “Making History and the Work of Memory in the Art of Edouard Duval-Carrié,” in Paul B. Niell, Michael D. Carrasco, and Lesley A. Wolff, eds., Decolonizing Refinement: Contemporary Pursuits in the Art of Edouard Duval-Carrié (Tallahassee: Museum of Fine Arts Press, 2018), 32. Indigenous revolutionaries suffered a similar fate. In the southern Andes, no known portraits survive from the period of the Tupac Amaru Rebellion (1780-1783), yet successive generations have sought to represent Tupac Amaru in step with the historical and cultural currents of the moment. See Leopoldo Lituma Agüero, El verdadero rostro de Túpac Amaru (Perú, 1969-1975) (Lima: Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, 2011). For more on Touissant, see Helen Weston, “The Many Faces of Touissant Louverture,” in Agnes Lugo-Ortiz and Angela Rosenthal, eds., Slave Portraiture in the Atlantic World (New York and Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 345–74.

- [36] María Elena Ortiz, ed., Firelei Báez: Bloodlines (Miami: Pérez Art Museum Miami, 2015).

- [37] https://www.nypl.org/events/exhibitions/firelei-baez-joy-out-fire (accessed July 31, 2021).

- [38] Interview between Isabel Custodio and Firelei Báez: https://www.moma.org/magazine/ articles/16 (accessed July 31, 2021).

- [39] For further discussion see Byron Ellsworth Hamann, “Interventions: The Mirrors of Las Meninas: Cochineal, Silver, and Clay,” Art Bulletin, vol. 92, no. 1/2 (March/June 2010), 19–21.

- [40] Interview between Isabel Custodio and Firelei Báez: https://www.moma.org/magazine /articles/16 (accessed July 31, 2021).

- [41] Mirzoeff, The Right to Look, 2–25.

- [42] My thinking on visual reckoning is deeply inspired by Cheryl Finley’s notion of “mnemonic aesthetics,” or ritual acts of remembering that involve Black contemporary artists’ “ritual sojourns to the past” to engage with visual archives of the transatlantic slave trade. See Cheryl Finley, Committed to Memory: The Art of the Slave Ship (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2018), 11.

- [43] For a critical intervention, see Denise Murrell, Posing Modernity: The Black Model from Manet and Matisse to Today (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2018).

- [44] Erica Moiah James, “Decolonizing Time: Nineteenth-Century Haitian Portraiture and the Critique of Anachronism in Caribbean Art,” Nka: Journal of Contemporary African Art, vol. 44, no. 1 (2019), 8–10.

- [45] Ibid., 10.

- [46] In reference to the creation of multiple copies of Richard Evans’s Henry Christophe, King of Haiti (1816), she argues, “Repetition and dispersal provided assurance that the image, if not the painting itself, would enter history.” James, “Decolonizing Time,” 16.

- [47] Ariella Aïsha Azoulay, Potential History: Unlearning Imperialism (London and New York: Verso, 2019), 289.

- [48] One notable recent example of the great strides that can be made in linking historical and contemporary archives, objects, and oral histories in the recovery of the voices, lives, and the creative expression of the enslaved and their descendants can be found in the Rijksmuseum’s exhibition Slavery and its associated catalogue. Divided into ten stories of historical figures connected to the Dutch slave trade, these vignettes bring to life a wealth of artworks, archival documents, and creative expressions drawn from both the museum’s collection and their contemporary collaborators in the Caribbean, Suriname, and Brazil. In particular, the chapter on Tula, the leader of a slave rebellion in Curaçao in 1795, deeply resonates with the themes presented in this article. Similarly to Tupac Amaru, no known large-scale historical portraits survive of the insurgent leader. Yet through careful analysis of two reports of the rebellion penned by a garrison captain and a priest, the curators bypassed the official archive of the uprising. To supplement these accounts, they reproduce the extraordinary 1958 testimony of a 105-year-old woman named Ma Chichi, born ten years prior to the abolition of slavery whose grandmother was born around the time of the rebellion. Her discussion of popular songs commemorating the abolition of slavery are matched with musical instruments of Curaçao drawn from the museum’s collection. In the centering of oral histories by descendant communities, the curators are able to establish hitherto unconsidered entanglements between textual archives, prints, musical instruments, and photographs that articulate an extraordinary narrative of resistance, abolition, and collective memory in colonial and contemporary Curaçao. See Valika Smeulders, “Tula: Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity,” in Eveline Sint Nicolaas and Valika Smeulders, eds., Slavery, (Amsterdam: Atlas Contact and Rijksmuseum, 2021), 220–39.