The Distributed Artist as Media Hero: On Relatability, Prints, and Israhel van Meckenem

Exhibition review: “Art of Enterprise: Israhel van Meckenem’s 15th-Century Print Workshop,” Chazen Museum of Art, Madison, December 18, 2023 – March 24, 2024.

The onset of print technology in Europe is a commonplace origin point for the historiography of media and communications theory. The art history of the first centuries of European printmaking has accommodated central axioms and practices of such theory: that media themselves construct reality and meanings for their audiences; that media operate and circulate more or less independently of their makers (or at least are discussed independently!); that media are subject to market forces militating toward profit and/or power.[1] The indispensable work of John Landau and Peter Parshall, exhibitions like Origins of European Printmaking, and the foundational collecting practices and writings of William Ivins emphasize, among other things, the ways that properties of technical printmaking influence artistic decisions and prints’ significance, the controversies of artistic property, and decisions made or rued based on labor costs.[2]

But in some ways these efforts remain subservient to enduring narratives of Renaissance artistic achievement operating within art historiography rather than media theory discourses. Recent print scholarship has foregrounded the importance of medium as a shaper of production; the metaphorics of medium; metaphors’ implications for artistic authorization.[3] Yet the best exhibitions (including the one mentioned above), even as they shy away from homage to individual artists, highlight the way print constitutes and reinvents new forms of artistic sophistication in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.[4] The most media-studies-like exhibitions of prints of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries have come from projects grounded in contexts of knowledge production.[5]

The exhibition, “Art of Enterprise: Israhel van Meckenem’s 15th-Century Print Workshop” (Chazen Museum of Art December 18, 2023 – March 24, 2024), bridged art historical and media studies discourse in a new way. Dr. James Wehn, Van Vleck Curator of Works on Paper, centered the printmaker’s wily, technically brilliant entrepreneurship as the production not so much of an individual as of a self-distilled visual brand, one as radically protean and unstable as circulation itself. (The show’s beautifully produced eponymous catalogue is complimentary and still available from the museum as of this writing.)[6]

Based in Bocholt, Germany, near the Rhine and the Low Countries, Israhel van Meckenem was a prolific late-fifteenth-century engraver, best known for his interest in copies and variants on other printmakers’ works. Self-identifying in at least one print as a goldsmith, he seems to have trained with the Master E.S. (an influential engraver identified only by his signature “ES,” which appears on some of his prints) or at least inherited several of his engraved plates, which Israhel then reworked. Israhel’s later releasing his own reworked versions of his own plates indicates a general interest in reworking and re-releasing that anticipates the evocative edits of the later etching master Rembrandt van Rijn, who often produced movingly altered versions (or “states”) of his own plates.

In much previous scholarship, Israhel emerges as a maverick, even a pirate profiting off others’ original work. Though intellectual property as a concept was still in flux at this time, Israhel previously seemed to me at best a gimmick artist present for the onset of gimmickry’s coadjutant, capitalist market practices.[7] Wehn’s curatorial vision instead complements the previous writing of Christof Metzger, who gave an account of the ways in which Israhel’s copying practices extend and transform previous artistic labor traditions.[8] The show’s Israhel is an ancestor to present-day media practices in a range of genres: the replica subset of his oeuvre, wonderfully represented in the show—especially by a sequence of St. Anthony Tormented by Demonses by Martin Schongauer, Master FVB, and Israhel, cat. nos. 39-41—is not the focus but merely represents one of many ways in which Israhel harnessed mass media’s circulatory essence.[9]

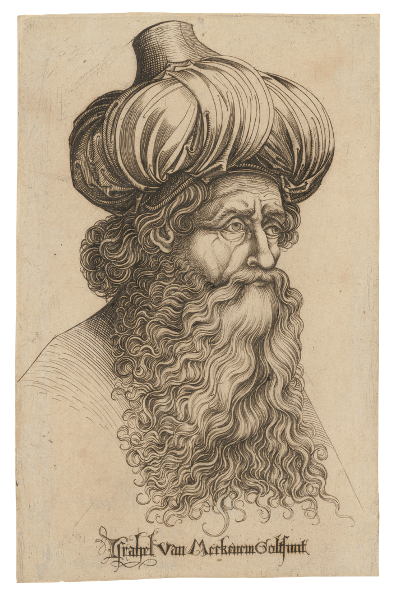

In all Israhel’s many enterprises, whether devotional, recreational (related to playing cards), artisanal (designs for other artists’ use), or self-promotional, he was teaching buyers to appreciate the luxury of engraving. In one image of a turbaned man, where Israhel explicitly signs as a goldsmith, this effort appears to extend an already established community of patrons into the world of engravings (cat. no. 2). Israhel cannot be a hero of old-school art historiographical narratives, but as he distributes himself in signature across a disparate array of works achieved in differing styles and for varying purposes, he is an early hero of media history.

Alongside the comparisons to contemporary media, the show’s greatest generosity lay in how accessible it made Israhel’s alterity to the present. The main gallery centered on a display case conveying the engraving process thoroughly, including five different period tools involved—scribe, burin, scraper, burnisher, and engraver’s pad—alongside a sample plate and engraving, as well as an enlarged reproduction of the famous sixteenth-century printmaking scene from Stradanus’s Nova Reperta. Such a case devoted to artistic process or media techne has become a standard of many exhibitions, but this one was particularly successful, drawing in museumgoers who peered at length, muttering to one another about their own prospects for success as engravers.

Approaching the show, a viewer faced at a distance Israhel’s self-portrait with his wife, Ida (cat. no. 1). Chosen for its legibility and indeed relatability, the print is presented also as deeply weird: itself the earliest known printed self-portrait, it had no peers for more than a century in terms of a printed self-portrait with a spouse (i.e., till Rembrandt and Saskia came along). Nearby, an indulgence print (cat. no. 3) came with a succinct yet comprehensive account of the indulgence industry that translated the invisible pretext for the print into terms even the most secular and/or uninitiated viewer could understand.[10] And the introductory text for the exhibition on the hallway leading to the show emphasized prints’ newness in culture, and the way Israhel had to reckon with potential buyers’ unfamiliarity with print as a sophisticated or luxury medium. These and other gestures throughout the show were exemplary in their inclusivity without any compromising of the otherness of the past.

This enforcement of otherness was a much-needed counterbalance to the first sentence of the large-fonted orange paragraph fronting the opening text of the show: “Israhel van Meckenem was a fifteenth-century media influencer and entrepreneur.” The show’s gambit of relatability was so overt it invited assessment by experts of its successes and its risks. The obvious objections are that any present-day audience engagement gained by anachronistic terms like “influencer,” “selfie,” and even “brand” is insufficient to cover the loss of historical specificity and artworks’ particular potential access to the past as other. (I myself balked at the characterization of Israhel as a capitalist at one saucy moment in Wehn’s catalogue essay, mostly because it was unrelatable to Israhel.)[11] One influential twenty-first-century theory defines Renaissance artworks by their internal tension between transhistoricity and reference to a specific historical context of making.[12] Whatever one’s art theory, the loss of the specificity of art’s context threatens to flatten art and drain it of its power.

I have often been impatient with such objections, which imply distrust in viewers’ ability to absorb difference. The installation, giving ample room to each print or group of related prints, laid the foundation for viewers to have the room to think about each context of making and its alternate reality. The placards delivered relevance alongside lucid accounts of each print’s place in that distant world. Indeed, viewers may not properly appreciate art’s (or media’s!) alterity unless they are incentivized to do so by a sense of relevance. Comparing selfies and self-portraiture may be a staple of art history lite, but I never so deeply experienced the specific power of Israhel’s Self Portrait with His Wife Ida until I thought more about how many functions it shared with a selfie, how weirdly it went about fulfilling those functions, and, ultimately, its unselfieness.[13]

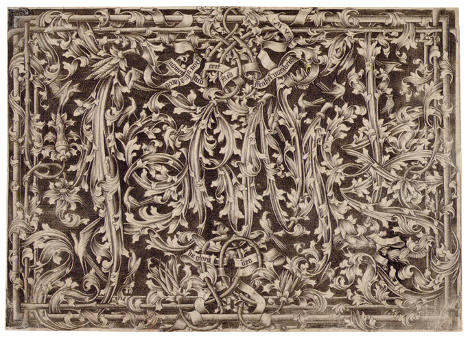

Whether because of the show’s outreach to the present or not, it made clear how much media studies stands to benefit from a better understanding of early media workers like Israhel. Imagine, for example, a reconsideration of teleministry of the last hundred years through the lens of Israhel’s work. Consider Israhel’s navigation of the indulgence craze of the late fifteenth-century both in works like the indulgence print mentioned above and his famous Man of Sorrows (Saint Gregory’s Vision) (cat. no. 63); his use of his full name in the foreground of many religious scenes, writ large relative to his peers’ signatures, which generally involved initials or monogram only; and most of all, his decision to make of his name itself a kind of theological event with multiple cultural resonances (Ornamental with the Engraver’s Name,cat. no. 59), beautifully analyzed by Wehn in the catalogue.[14] I hope the show inspires further comparative thought.

Until I saw this show—assembled with an unprecedented amount of long-distance loans, including more than a dozen from the Albertina in Vienna—I had never grasped Israhel’s own wrestling, so to speak, with the implications of print as medium. So many of his prints in the galleries had a mismatched duality or thematized asymmetry, including his Self-Portrait with His Wife Ida; pictures of other generic couples, including his wonderful Couple with Playing Cards, which lands just shy of the next generation’s Weibermacht trends (cat. no. 51); his Salome in which Salome stands just off-center (cat. no. 49); his near-identical ornamental prints of culturally risqué Morris Dancers and the religiously foundational Tree of Jesse (cat. nos. 44-45); and so on. Despite Israhel’s claim in his Man of Sorrows (Saint Gregory’s Vision) of an “ymago contrafacta,” “an image corresponding”[15] to its counterpart in Rome, Israhel often thematized doubling as productive rather than reproductive, as uneven, even unclean. Like many artists, he was also a media theorist.

- [1] Examples of canonical books containing some of these axioms and scholarly practices include Jean Baudrillard, Simulacres et Simulation (Paris: Éditions Galilée, 1981); Stuart Hall, Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices (London: Sage and Open University, 1997); James Curran and Jean Seaton, Power without Responsibility: Press, Broadcasting and the Internet in Britain [first ed. 1981] (New York: Routledge, 2018).

- [2] See David Landau and Peter Parshall, The Renaissance Print: 1470-1550 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1996); Peter Parshall and Rainer Schoch, Origins of European Printmaking: Fifteenth-Century Woodcuts and Their Public (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006), for the catalogue associated with the abovementioned show; William Ivins, Prints and Visual Communication (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1953); and Freyda Spira with Peter Parshall, The Power of Prints: The Legacy of William M. Ivins and A. Hyatt Mayor (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2016).

- [3] Some of the most interesting recent English-language scholarship reconsidering print as medium includes the work of Femke Speelberg, Susanne Meurer, Shira Brisman, and Suzanne Karr Schmidt: see for example Femke Speelberg, “‘noch vil höher, und subtiler Künsten . . . an tag zu bringen’: Renaissance Pattern Books and Ornament Prints as Catalysts of the Design Process,” Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte, vol. 87 (2024), 48-67; Susanne Meurer, “Translating the Hand into Print: Johann Neudörffer’s Etched Writing Manual,” Renaissance Quarterly, vol. 75 (2022), 403-58; Shira Brisman, “Contriving Scarcity: Sixteenth-Century Goldsmith-Engravers and the Resources of the Land,” West 86th, vol. 27 no. 2 (2020); and, a particularly indispensable resource on print use, Suzanne Karr Schmidt, Interactive and Sculptural Printmaking in the Renaissance (Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2018).

- [4] See, for example, Catherine Jenkins, Nadine M. Orenstsein, and Freyda Spira, eds., The Renaissance of Etching (New Haven and New York: Yale University Press and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2019); Naoko Takahatake, The Chiaroscuro Woodcut in Renaissance Italy (Los Angeles, New York, and Munich: Los Angeles County Museum of Art in association with DelMonico Books-Prestel, 2018); Michael Cole, ed., The Early Modern Painter-Etcher (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2006); and Martin Sonnabend, Vor Dürer: Kupferstich wird Kunst (Frankfurt: Sandstein Verlag, 2002).

- [5] The central example is Susan Dackerman, ed., Prints and the Pursuit of Knowledge in Early Modern Europe (Cambridge, MA, and New Haven: Harvard Art Museums and Yale University Press, 2011).

- [6] James Wehn, Art of Enterprise: Israhel van Meckenem’s 15th-Century Print Workshop (Madison: Chazen Museum of Art, 2023).To obtain this catalogue, please write to reception@chazen.wisc.edu. Full disclosure: I am mentioned in the acknowledgments but did not work on the show and found it a surprise.

- [7] For the canonical study of intellectual property and Renaissance prints, see Peter Parshall, “Imago contrafacta: Images and Facts in the Northern Renaissance,” Art History, vol. 16, no. 4 (December 1993), 554-79. For the gimmick, see Sianne Ngai, Theory of the Gimmick: Aesthetic Judgment and Capitalist Form (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2020).

- [8] Christof Metzger, “Multiplikator des Ruhmes: Israhel van Meckenems Kopien vor dem Hintergrund spätmittelalterlicher Traditionsgebundenheit,” in Achim Riether, Israhel van Meckenem (um 1440/45-1503): Kupferstiche—Der Münchner Bestand (Munich: Staatliche Graphische Sammlung München, 2006), 39-47.

- [9] “Circulation” is identified by Scott and McKenzie Wark as the fetish of media studies in the Marxist sense of the fetish as what divides labor from value, as well as in other anthropological senses. See Scott Wark and McKenzie Wark, “Circulation and Its Discontents,” in Alfie Bown and Dan Bristow, eds., Post Memes: Seizing the Memes of Production (Santa Barbara: Punctum Books, 2019), 293-318, here 296-97.

- [10] The indulgence industry rose precipitously in the fifteenth century around Church-authorized pilgrimages and artworks (including prints), participation in which granted an indulgence, a fixed reduction of time spent in purgatory after death and prior to entering heaven. The best recent resource on these indulgences is Kathryn Rudy, Rubrics, Images and Indulgences in Late Medieval Netherlandish Manuscripts (Brill, 2016).

- [11] James Wehn, “Israhel van Meckenem and His Printmaking Enterprise,” in Wehn, Art of Enterprise, 6-29, here 28.

- [12] Alexander Nagel and Christopher S. Wood, Anachronic Renaissance (New York: Zone Books, 2010).

- [13] Another recent admirable show staging early modern prints in twenty-first-century terms that helped clarify their historical specificity was Jun Nakamura’s “Macho Men: Hypermasculinity in Dutch & American Prints” at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, August 27, 2022 – March 20, 2023, which brought together c. 1590s Dutch prints linking brawn to nascent Dutch statehood and Depression-era prints from the United States celebrating the grit of the working class man.

- [14] Wehn, “Israhel,” here 26-27.

- [15] “Imago contrafacta” means literally a “counter-made” image, where “counter-” functions in the sense of reciprocity (OED, s.v. counter- [prefix], 2.d.), unlike in its English cognate “counterfeit.”