“This Is the Future Liberals Want”: The Crisis of Democracy and the Salon des Indépendants in Interwar France (1918–1939)

Introduction

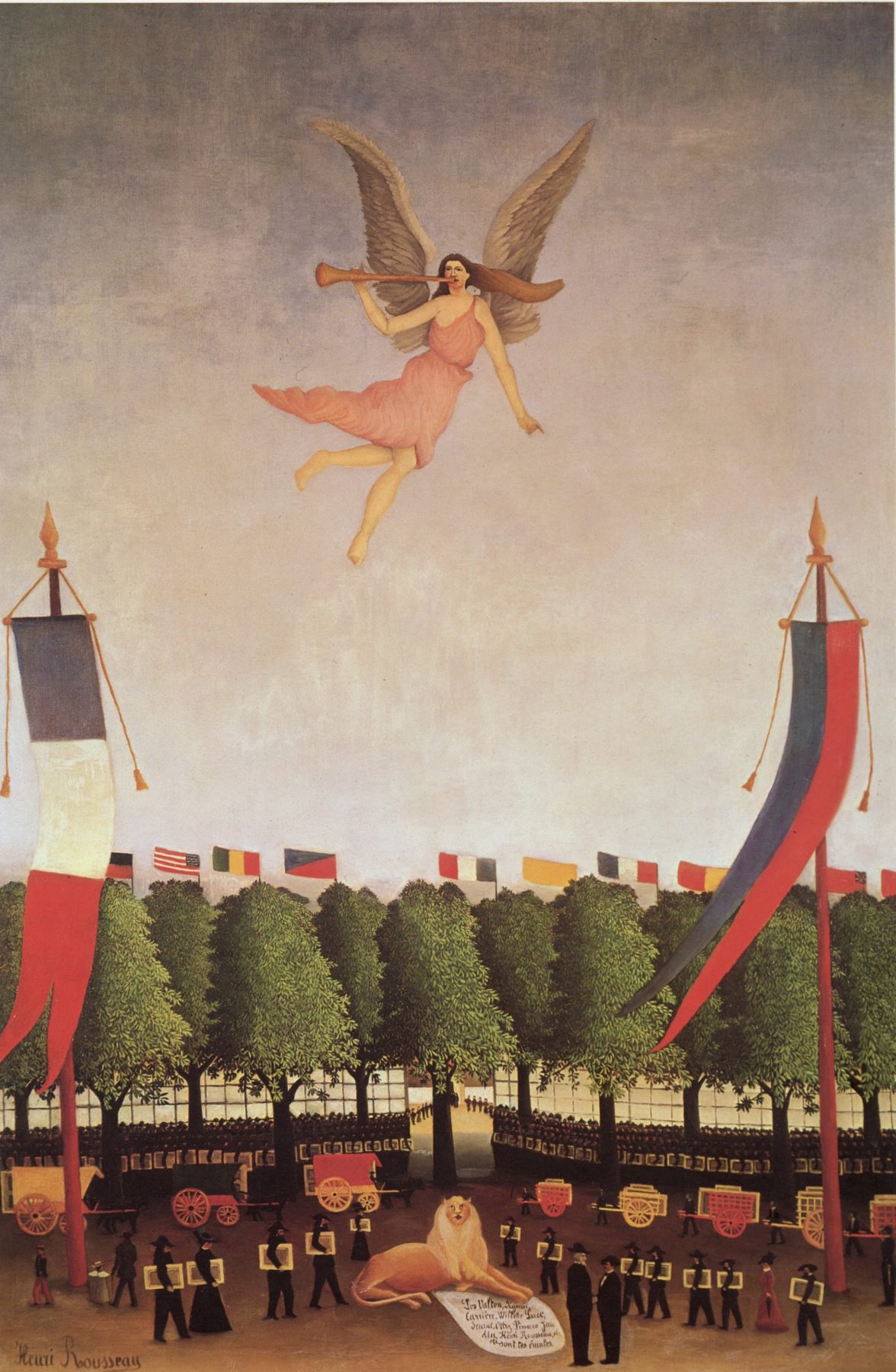

In 1906, the painter Henri Rousseau’s submission to the annual Salon des Indépendants was an hommage to the institution itself. In his painting, entitled Liberty Inviting the Artists to Take Part in the 22nd Exhibition of the Indépendents, an allegory of Liberty hovers over the Grand Palais, the annual site of the art exhibition, beckoning an orderly queue of male and female artists through its gates. Indistinguishable in their modern black dress, each artist clutches a single canvas, a visual echo of the Republican slogan, “one person, one vote,” while at the bottom of the painting, the lion, an emblem of universal suffrage, holds a decree that lists some of the past exhibitors to the Indépendants as the new anti-academic establishment in French art: “The Valtons, Signacs, Carrières, Willettes, Luces, Seurats, Ortizes, Pissarros, Jaudins, Henri Rousseaus, etc., etc., are your emulators.”1 Above the tree line, the flag of the French Third Republic (1870–1940) and the flag of the Salon des Indépendants join those of other nations to represent the multinational exhibitioners. The Salon des Indépendants—its slogan: “neither jury nor prizes”—holds an important place in the history of modernism.2 As one of the first artistic salons to admit entrance to any artist, regardless of their skill, nationality, or gender, it would provide an institutional context for some of the most important avant-garde gambits of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.3 Though Rousseau’s painting was intended as an ode to the salon that had helped the customs agent launch a career as a painter, the work’s symbolism drew directly from a trove of Republican imagery that celebrated equality, universal suffrage, and the opening of the territory to citizens of other nationalities.4 As the painter recognized, the open salon or salon libre was a quintessentially Republican institution, whose genesis could be traced to the formative years of the French Revolution a century earlier. During the ancien régime, the only public space for artists to exhibit had been the crown’s official salon, a nepotistic, juried institution whose default sanctioning of the baroque style was indelibly linked to a corrupt autocracy.5 Dismantling the jury had thus been a priority for revolutionaries like Quatremère de Quincy and the more militant Jacques-Louis David, leader of the Commune des Arts. During the constituante nationale, these Jacobins called for a salon libre open to all. Underscoring the theoretical links between political and artistic representation, and between political and artistic speech, they had put forth a set of principles that would later prove to be defining features of artistic modernity: “The equality of rights that is the base of the Constitution has permitted all citizens to expose their thought; this legal equality should then also permit all artists to expose their works; his painting is his thought; his public exhibition is the permission to print.”6

A free salon also meant freedom from the partisan judgment of the state, an aesthetic independence that Quatremère had argued would always reap the greatest artistic fruit for the nation.7 Thoughthe revolutionaries did host a salon libre in 1791, it survived neither the National Convention (1792–1794) nor the Directory (1795–1799).8

The French would have to wait until the return of Republicanism, with the Third Republic of Jules Ferry and Léon Gambetta, for the liberalization of artistic representation to finally take effect.9 Partisans of a free press, male universal suffrage, and private enterprise, the administrators of the Third Republic established an artistic policy of eclecticism and “strategic nonintervention” in the arts.10 In early 1881, the state would thus renounce its stewardship of an official salon, extricating itself from political controversies indelibly linked to the ancient regime.11 In line with the policies of capitalist liberalism, the qualities believed to be crucial to the cultivation of national talent under the new Third Republic were independence and individualism (including a fragmented art market).

The advent of the autonomous Salon des Indépendants, run entirely by artists, neatly coincided with this Republican position. Despite the rebellious characterization that its chroniclers have assigned it, state and municipal officials immediately recognized its value.12 Marking the institutionalization of values wished for in the crucible of early Republicanism, its representational structure also concretized the stated values of the Third Republic: rehearsing the principle of male universal suffrage (established in 1875 with the loi Wallon) while also serving a politique culturelle [ca. 1880] of broader artistic access and education for the public.13 By the 1920s, the Indépendants would be granted official state recognition as a public utility.14

Rousseau’s painting of the Indépendants thus celebrated not only the institution itself but the (fictional) achievement of Republican cultural democratization first proposed in the Jacobin reenvisioning of French society during the revolution of 1789. The painting optimistically symbolized the closing of one political chapter, marked by autocracy and hierarchies, and the advent of a new one.15 Chronicles of the Indépendants (most of them quasi-hagiographic and produced by the still-extant salon to coincide with landmark anniversaries) emphasize this utopian imaginary.16 Unfurling like political allegories, these histories begin with an obligatory denunciation of the official state salon and its “totalitarianism” over a people of artists.17 They chart the rise of independent art and the autonomous exhibition practices of Gustave Courbet, Édouard Manet, and the Impressionists, celebrate the opening of the Indépendants by a motley group of artists (including the anarchist Paul Signac) in 1885, and cite the groundbreaking but institutionally ignored artists and movements that debuted there.18 These include Vincent van Gogh (exhibiting there from 1888–1890), Rousseau (1886–1911, 1926), Wassily Kandinsky (1907–1912), and movements like Neo-Impressionism (in the 1880s and 1890s), Fauvism in 1905, and finally the so-called coup de cubisme of 1911, when “salon” cubists like Albert Gleizes and Jean Metzinger displayed all their work as a group in room 41.19 In each of these cases, the salon permitted an artistic tendency that a jury might not have accepted, providing an institutional crucible for new movements to emerge in France.20

With the advent of the Indépendants, it would appear that a protracted, century-long debate over political and aesthetic representation dovetailed into a happy conclusion, an achievement that Rousseau’s own improbable success might have marked as a fait accompli.21 However,parallel to this achievement also came its challenge, in the form of an increasingly vocal and unquestionably powerful far-right movement resentful of the revolution’s legacy and cynical about how the principles of the Enlightenment had been put into practice. In the first decades of the twentieth century this symbolic salon would become a regular site of contestation and mockery in far-right journals and newspapers opposed to Republicanism and the “independent” art it encouraged. As the neo-Catholic painter Maurice Denis (a sympathizer of the militant Action Française) would complain in one of the earliest examples of such a challenge, the Indépendants “systematized” and “held up a precise reflection” of “the anarchist tendencies, the lassitude and incoherence of our art.”22

By the 1920s, such comments would become a common refrain, heard annually in the publications of Action française and in populist reactionary weeklies like Je suis partout, and rearticulated in the 1930s in the writings of French critics sympathetic to different strands of Fascist thought. Little but a pretense to counter political and artistic “independence,” these reviews rarely discussed the art on display, laboring instead to skewer the Salon des Indépendants as an exemplum for democracy’s failings. That is, for right-wing French commentators in the early twentieth century, the Indépendants encapsulated (to borrow a phrase from present-day memes) the dreaded “future that liberals want.” In what follows, I chart the evolution of this discourse, which over the course of two decades revealed an increasingly radicalized press corps that weaponized art criticism for political aims. Shedding light on a body of art-critical literature that served Fascist ideologies of violence, I argue that these reviews provided the journalistic Right with an occasion to propose antidemocratic countermodels—not only of autocratic artistic support but of autocratic statecraft. This literature conflated the qualities of artistic selection and those of political organization. Enacting a dangerous aestheticization of politics described in the writings of Walter Benjamin, it served as a platform upon which to reenvision the aesthetic and political sphere according to a plan very different from that of the egalitarian utopia painted by Rousseau.23

I. Philosophical Issues: The Right to Exhibit, Negative Freedom, and Numerisme

Despite the contestation that was to come, the soon-to-be ubiquitous Republican analogy is altogether absent in the earliest reviews of the Indépendants and is unique to twentieth-century criticism. In the institution’s first decade, reviewers associated it with another Salon des refusés, while movements like Impressionism and Neo-Impressionism framed their discussions.24 In the first decade of the twentieth century, the credibility of the institution would solidify, with socialist art critic Roger Marx announcing in 1903, “nobody thinks now to contest that the salon has acquired with time an importance and a great interest.”25 If we are to believe Gertrude Stein, by 1910 the Indépendants had become “the big event of the year… Everyone talked about the scandals that would or wouldn’t emerge.”26 Around this time the Indépendants began to function as an artistic “barometer” (Guillaume Apollinaire’s phrase) and as a yearly magic mirror, giving whoever looked into it the image they had already preconceived of French art and society. This was also the period when the discourse around the salon began to take on a heightened political tenor, as it began to serve as a platform upon which to return to the core principles of Republicanism—or as a straw man to critique those principles.27

In the 1905 review of the Indépendants printed in L’Humanité, the official organ of the French Socialist Party, Republican principles were clear points of reference.28 According to the critic Gustave Rouanet, the right to exhibit at the Indépendants, which represented “perfect justice in exhibitions,” was comparable to the inalienable political rights of free speech and representation: “All producers have the absolute right to exhibit their works… It is an organization based on the right of the individual, and the public should support it with their presence.”29 For reviewers on the left, this would form the bedrock defense of the salon, even if these reviewers were sometimes unhappy with the results. Reviewing the uneven Indépendants for La revue des beaux-arts in 1907, Henry Revers defended the abundance of “croutes” (bad paintings) as a necessary “consequence of the principle” of total liberty. Avowing that the only “real path toward truth” was freedom, he pledged to always “applaud an attempt whose unique status affirms the same right for all.”30

In addition to questions of expressive freedom, reviewing the Indépendants also provoked broader questions regarding the capacity of the public to engage responsibly in the political or public sphere. In the discourse of optimistic socialists prior to the First World War, the Indépendants signaled the evolution of collective governance. In La chronique des arts in 1903, Marx wrote that the salon and the new aesthetic sensibilities it invited would provide citizens with an opportunity to rehearse their critical thinking and develop a better, more “lucid” sense of political judgment.31

Marx would refine these thoughts in 1905, arguing that the novelty of the salon encouraged a kind of Bergsonian “creative evolution”; that is, it cultivated the aesthetic “variations that direct the evolution of man and societies.” For him, the Indépendants was a sign of progress within human history, an imperfect institution that could, like the Republic, adapt over time to the needs of the people: “Is [the Indépendants] not truly the Salon for our nation of artists, of our Republic free of the burden of outdated prejudices, one that lends to the communion of the creator and the spectator, where each and all can work, show, judge in his own way, without control or hindrance, in the plentitude of sincere faith in free judgment?” Dismissing the question of whether those showing were capable artists, Marx prioritized creativity above all, writing that the question of “means” was less important than the question of the “gift, of invention and of originality.”32

Predisposed as they were to detest anything associated with the legacy of the revolution, for critics on the Far Right the Indépendants epitomized misguided democratic ideology. Since the Dreyfus affair, the neo-Catholic integral nationalist Charles Maurras, poet and editor of the reactionary Action française, had been mounting a rigorous and sincere press campaign to dismantle the Third Republic and reinstate the Bourbon dynasty. Deploying the positivist theories of mass psychology (proposed by Frédéric le Play, Auguste Comte, Gustave Le Bon, and Gabriel Tarde), Maurras had for years insisted that an individual decision-making process was superior to democratic deliberations, which led to random and “irrational” results.33 This argument was put forth in a 1905 issue of Action française that excerpted some of the proceedings of the Jacobin Société populaire et républicaine des arts (1791–1795) and included a set of cynical annotations by the conservative art historian Henry Lapauze, who in his full-length book transcribing these proceedings had accused the revolutionaries of being “absolutely ignorant of psychological laws.” Lapauze argued that their commitment to the principles of equality had “paralyzed their capacity to make decisions in the realm of artistic governance,” and he blamed them for the “causes of ruin” in contemporary art.34 Lapauze had observed, “All evidence point[s] to a fact that would take much longer to be discovered in the political realm: in the domain of art, the tyranny of an ignorant mob is just as oppressive as the oligarchy of the elite, and brings the rest to autocracy.”35 Concluding Lapauze’s excerpt, Henri Mazet, an editor at Action française, wrote that French art would continue in decadence until “the restoration of royal power.”36

In their annual reviews of the Indépendants, conservatives regularly evoked the despised principles of David and his comrades. In a 1908 review for Action française, the critic Maurice Pujo railed against “the old idea of the ’89-er and ’48er” and asserted that “independence… [was] a purely negative concept, which, in the domain of arts and letters, as in others, leads to nothing but sterility.”37 Writing on the salon for La grande revue that same year, Maurice Denis called the Indépendants a sample-sized experiment for majoritarianism and introduced the idea of numerisme, a term coined by the antidemocratic Catholic poet and essayist Adrien Mithouard38:

The Indépendants have, for 24 years, provided a complete and conclusive experiment in democracy. Anything that meets the bare minimum to be considered a work of art has been liberally exhibited. It has been the triumph of what Adrien Mithouard calls numerisme: a system of absolute individualism, at the mathematical level, where individuals and works are considered exactly equal and interchangeable, as equivalent units… Yes, the experiment has been rigorous. The result is now apparent. The theory of the wide door substituting the narrow… has favored invasion, and has placed mediocrities in the limelight.39

In 1934, Maurras’s young follower Philippe Besnard (son of the conservative painter Paul-Albert Besnard) would expand on these assumptions in his book La politique et les arts, repeating the Maurassian argument that democratic modes of judgment were conducive neither to politics nor art. “By definition,” he stated bluntly, “universal suffrage is detrimental to the arts, which should not be upheld to the incompetent and fanatical masses for judgment.”40

II. Exhibition as Republic: The Cosmopolitan Salon

If universal suffrage had “Made the people into an assembly of kings,” as the socialist orator Jean Jaurès claimed, it is just as true that the Indépendants had made the people into an assembly of artists, for better or worse.41 Another important defense of the salon libre was that it would prevent future embarrassing incidents of “neglected geniuses” later being upheld as national treasures. As one supporter of the salon reasoned in 1921, “It is better to accept one hundred bad canvases than to reject one of genius.”42 However, no limits on who was an artist meant that the salon would continue to grow in size each year, stretching to accommodate a theoretically boundless number of art works. In 1910, the Indépendants that Apollinaire reviewed had 5,321 works submitted by 1,182 artists, resulting in a lengthy report that L’Intransigeant had to stretch out over three days, the last one entitled, “We continue our walk along kilometers of painting.”43

Within a decade of Rousseau submitting his “ode” to the Indépendants, the initial appeal of the salon libre would cede to constant complaints about overcrowded walls and a surplus of middling artists.44 In 1919, a critic from Art et les artistes wrote that exhibition visitors were “Overwhelmed by the multitude of works” and “walked by them too quickly to really distinguish what merits attention.”45 Though the salon’s organizing committee reduced the number of submissions per artist from five to three in 1921, and then again to two in 1923, the number of exhibitors increased throughout the 1920s, fed by more would-be artists and a buoyant international market for a modernism that was “made in France.”46 But judging by the jokes in the journals of the period, an increasing number of these new exhibitors were so-called peintres de dimanche, or Sunday painters.47 Nevertheless, loyal to their principles, the organizing committee of the Salon des Indépendants would not deviate from its open policy, with Signac (the group’s president) announcing bluntly, “We are not concerned with whether or not good or bad painting is exhibited with us. We want only to be administrators.”48

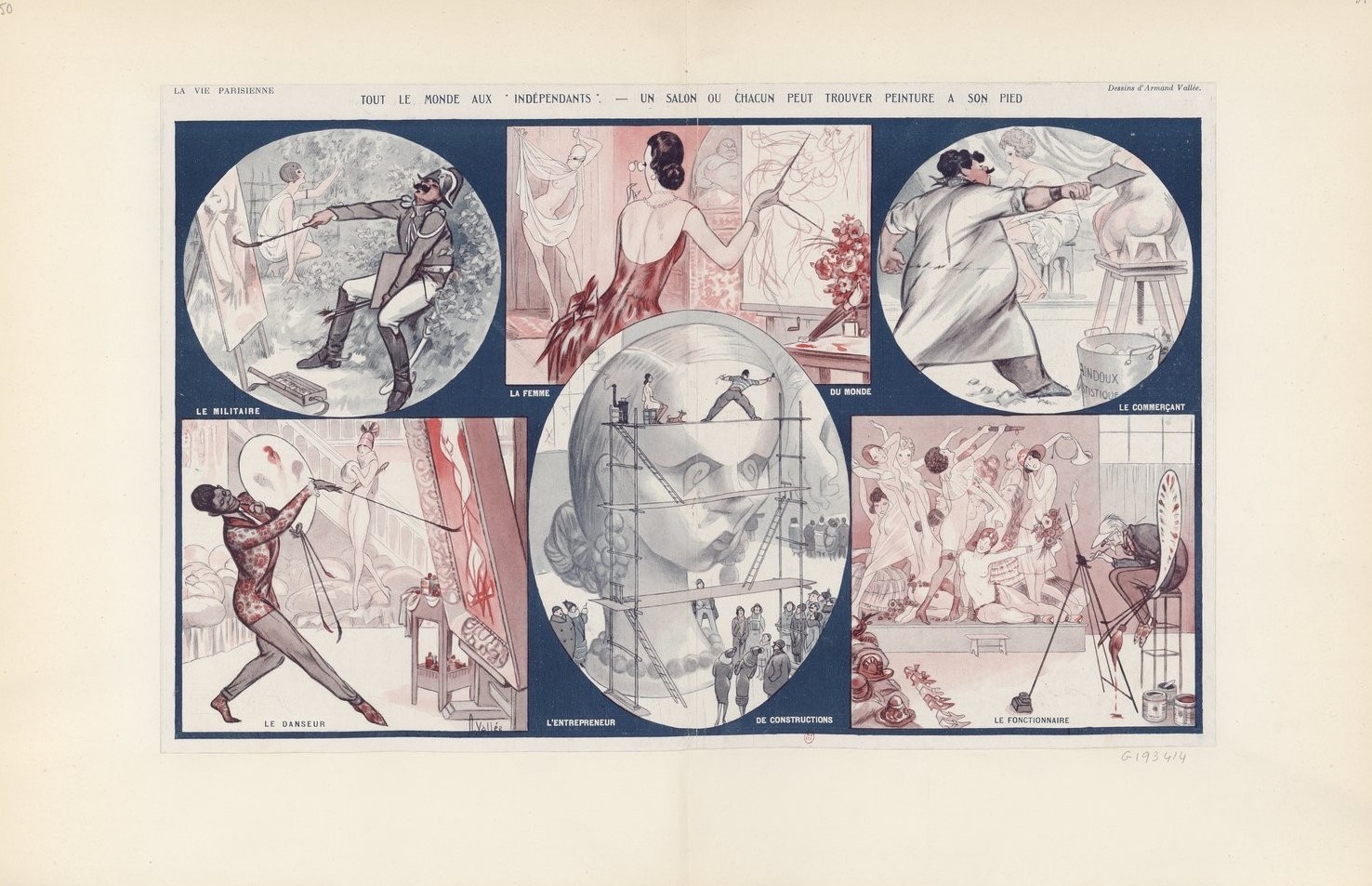

Soon the “republic of painters” conjured by Rousseau had been replaced with the image of a pluralistic amalgamation of individualities. In 1925, the tabloid La vie parisienne printed Armand Vallée’s satire captioned “Everyone at the Indépendants—a salon where all can find the painting that suits them.”49 The illustration features six exhibitor types, none presenting as professional artists but each exercising their “right” to artistic representation: a military general attacking a canvas of angular forms, a lithe dancer daintily tipping his brush on an easel of arabesques, and a fonctionnaire so engrossed in the minutiae of cataloguing the line of ladies’ shoes before him that he neglects the tangle of artist’s models to his right. Like Rousseau’s picture, Vallée’s satire speaks to the egalitarianism of the salon. But instead of a deindividualized mass of artists, the tokenism in this illustration is a cynical take on the pluralities expressed in the Third Republic of artists.

As art historians have established, from the late nineteenth century onward the Parisian art world had occupied itself in debates regarding the role of tradition and the place of “cosmopolitan” diversity in the fine arts, debates exacerbated by the association of modernist tendencies with foreign influence.50 In the years leading to the First World War, journalists assessing the range of nationalities on display at the Indépendants would repeat the exotic locales of all the exhibitioners with astonishment.51 This reporting was occasionally tinged with condescension, such as when Georges de Céli, in 1912, complained that the foreigners had too quickly “assimilated” the most recent artistic theorems, “offering a surplus of anarchy in exchange.”52

But in the period immediately after the First World War, the subject became more fraught. Not only had wartime nationalism inspired a vision of “a strong and national French art,” but the presence of immigrants in France had doubled, a shift reflected directly in the Salon des Indépendants.53 In 1920, of 1,141 entrants, 235 were nonnative artists; by 1923 almost half of the exhibitors were nonnative artists (755 of 1,660); and in 1926, more than half (1,118 of 2,000) were nonnative.54 Even liberal publications frequently expressed alarm at the increased presence of foreigners in the artistic salons, often singling out Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe.55 As foreign artists flocked to Paris to participate in a buoyant art market, critics for mainstream publications like L’amour de l’art, Le carnet de la semaine, and L’art vivant complained about the “torrent of foreigners with a noxious and weakening influence on indigenous artists.” With nationality at the forefront of artistic debate, in 1923 the organizing committee of the Indépendants passed a measure to separate the artists into sections based on nationality instead of by last name. Though the change was justified as having “the sincere goal of renewing interest in the exhibition,” it was perceived by many within and outside the organizing committee as a violation of the salon’s universalizing principles and an acquiescence to the demands of xenophobic and nationalist critics.56

“La querelle des Indépendants,” as the scuffle came to be known, was debated that year in a series of “Enquêtes” in Le bulletin de la vie artistique.57 For the French artist and critic Yves Alix, to separate artists by nationality was to disavow the Third Republic’s “ancient reputation of generous hospitality,” while foreign artists interviewed found the measure against the spirit of the Indépendants.58 Though Bulletin editor Guillaume Janneau expressed ambivalence about the change, he also wondered whether singling out the nationality of each artist would contradict the assimilative spirit of Republicanism. Would calling attention to French artists of foreign origin, he asked, not “brusquely erect a frontier between us and them?”59

Should the Indépendants match the (ostensibly) universalist Republic, a place where plurality was (again, in theory) encouraged, and where assimilation was the order of the day, orshould it circumscribe each nationality? Such questions reflected upon larger issues at the level of the state, as mounting xenophobia in the late 1920s saw critics on the right reconsidering whether the freedoms of the Third Republic should extend to citizens of foreign extraction and French residents of foreign nationality.60 As political conflict mounted throughout Europe, these questions became more pressing. In January 1933, immediately after Adolf Hitler became chancellor of Germany, France opened its doors to political refugees, an estimated 25,000 that year alone.61 Many on the extreme Right were concerned that the new arrivals would be just as indésirable in France as they were in Germany.62 In May of that year, Prime Minister Édouard Daladier warned that France’s generosity could be exploited, comparing the arrival of Hitler’s outcasts to the admittance of “a Trojan Horse of spies and subversives.”63

Thus, by the time that antisemitic critic Lucien Rebatet reviewed the Salon d’Automne in 1934, a xenophobic discourse to describe new immigrants was already well established in the press.Describing the open-door policy of the Salon des Indépendants as a flea market “invaded by Jewish vermin and three-franc lithographs like the dishonest fabric market at the Porte Montmartre,” he applauded, in contrast, the “hygienic” policies recently adopted by the Salon d’Automne to restrict the number of entrants.64 Incorrectly citing artists Jean Hanau, Max Band, and Charles Walch, none of them recent immigrants, Rebatet wrote that they represented “once more too many examples of this Jewish gangrene that decomposes form and color in sweat and syrup.”65 He reported with relief that, at the Salon d’Automne, “In all the exhibition rooms, in any case, foreigners have ceded the terrain. It is without a doubt one of the causes of unity and simplicity in the salon.”66 Mixing metaphors for the body, artistic and political representation, Rebatet found in the Indépendants an occasion to critique a Republic with liberal immigration policies.

III. Revisiting Independence and the Republic’s Laissez-Faire Approach to the Arts

The Indépendants provoked inquiry on how to best organize the arts, and, given the mediocre showing at the Indépendants in the 1920s, critics used the exhibition as a platform to reconsider the entire idea of artistic independence, asking whether the state should reestablish a stronger position in the guidance and encouragement of artists. In the first decades of the Indépendants, grouping works by tendency had been an important curatorial strategy, helping to publicize avant-garde groups as the cubists had done in 1911. But starting in 1920, the elected committee of the Société des Artistes Indépendants would stymie this strategy, alienating the avant-garde by passing a resolution to disallow the artists or their dealers any hand in the placement of the works submitted.67 As president, Signac was conscious that these efforts had displeased artists and their dealers.68 Sure enough, his stubborn resistance to hierarchy drove away exhibitors lucky enough to have galleries as alternatives.69 In 1923, Jacques Lipchitz, Francis Picabia, and Ossip Zadkine stopped submitting their works. Thereafter, the only avant-garde artists still participating on a yearly basis were Max Ernst, Gino Severini, and Metzinger. With the avant-garde abandoning the salons, the Indépendants began to lose its raison d’être as a clearinghouse for talent.

The committee’s refusal to allow any distinction among artists (other than nationality) was part of an emancipatory desire to allow the “public” to judge the art themselves. But in practice this process was the responsibility of critics. With the art on display proliferating every year, even critics writing for the most liberal publications began to resent the Indépendants. In 1925, Jacques Guenne, founder of the liberal arts weekly L’art vivant, announced that “the Salon des Indépendants has sunk deeper than ever into the quicksand of mediocrity.” Echoing the Far Right distrust of majoritarianism and evoking the “tyranny of the majority,” he wrote that “real art has always been a challenge to the taste of the multitude,” adding, “Here is the problem with our times.”70 Four years later, his journal would cease reviewing the Indépendants altogether.71 Unanimously, critics reviewing the Indépendants grew less convinced that the “public” was a sufficient judge of art. But some wondered whether the problem was more systemic. Was artistic “independence” still an approach capable of cultivating talent in France? By the end of the 1920s, commentators had begun to lose confidence in this long-fought-for principle.

In the interwar period, the laissez-faire market system for artistic production and the contradictions of artistic autonomy under capitalism became a target of criticism from the Left and the Right. On the left, the banality of the art in the interwar period, including that at the Indépendants, was a reflection of the capitalist system. In his 1927 review of the Indépendants in L’Humanité (since 1920,the official organ of the Parti Communiste Français, or PCF), Jacques Memmi suggested that the banality of the Indépendants was more likely the fault of the “decrepitude of art in bourgeois society” than the fault of the institution.72 The question of the artwork’s status within a flawed capitalist society was given more consideration in the monthly Marxist-Leninist revue Commune (1933–1939), another organ for the PCF, edited by the activist Paul Vaillant-Couturier. For the writers of Commune, the contemporary dealer-critic-salon system was considered a reflection of a division of labor that had “crushed” the talents of the masses at the expense of a specialized few obligated to limit themselves to the kind of work demanded by bourgeois clients.73

When the Right offered a critique of the artist’s dependence on the market, these comments drew on the discourse of anticapitalist antisemitism and stereotypes about Jewish art dealers as immoral “merchants of the temple.”74 Since 1919, the reactionary critic Camille Mauclair had complained that the “independent artist” of the day was “independent” only in name and in reality knelt in service to the “mercantile” forces in the art world.75 He would satirize these art dealers in 1929 as the Jewish fictional cabal of “Levy-Tripp, Gluant, Arsénieux, Bouc, Rosenscwein et Cie.”76 Like Philippe Besnard and other neo-royalists with whom he often sided, Mauclair mourned the loss of the aristocratic mécène, or patron, of the ancien régime. Arguing that the fine arts had flourished under historical monarchies and that the “ancestral connoisseurship” of the mécène permitted “enlightened choices,” antidemocratic critics would often mobilize this as proof of the superiority of political autocracy.77

Grumblings about the “mixed” system of independence that had dominated the Parisian art market in the 1920s began to grow louder as the French economy started to feel the effects of the American stock market crash of 1929. The market for modern art softened, with one third of the commercial galleries in Paris closing.78 While stories of artists “subsisting on weeds in the suburbs” were rampant in the art press, some artists turned to self-reliance and collective action.79 In March of 1933, a group of artists organized a month-long exhibition called a “collaboration” that redistributed 50 percent of all profits from any works sold to those who had not sold works in the show.80

Still, the list of exhibitors appealing to municipal and state coffers for welfare was “interminable,” and in March 1932 the Conseil Municipal of Paris allotted 40,000,000 francs to artists and artisans affected by the economic crisis.81 However, most of these funds went toward improving municipal buildings, leaving only 5,000 francs for fine art purchases. In 1932, a group of fifty-five artists representing several syndicalist groups petitioned the national chamber of deputies to lay claim to mutual funds that decrees from 1905 had offered to unsalaried independent manual laborers.82 The law was considered, but a change in the ministry, budget negotiations, and lack of feasibility eventually cut the proposition short.83 Over the course of the discussions, Anatole de Monzie (minister of education and fine art in 1933) spoke reassuringly that all would be done to help independent art workers. But rather than provide alms, de Monzie renewed the state’s commitment to be a purchaser and collector of modern art, marking the beginning of a two-pronged approach to support contemporary artists by actively purchasing more from salons and initiating ambitious public works commissions for the 1937 Exposition Universelle.84

Despite this mobilization, the fallout from the financial crisis had demonstrated the fragility of a market-driven, independent framework for supporting the arts, leaving both sides of the political spectrum unsatisfied. By the middle of the 1930s, proposals for more drastic reforms inspired by political developments abroad were articulated with more and more precision. While calls by reactionaries like Mauclair to “regulate” the art market had fallen on deaf ears, in the aftermath of an attempted coup by Far Right paramilitary leagues in February 1934, the possibility of overturning the Republican administration now seemed, to those on the right, more tangible.85

Precipitated in part by the Great Depression, other European states in the 1930s also saw initiatives for state-sponsored artistic production that would satisfy a “collective” need for a national art while also projecting an image of strength abroad. The revival of state involvement in the arts was the subject of an entire issue of the 1936 BBC magazine The Listener, featuring an article by a young John Maynard Keynes that argued for state involvement in the arts as a positive public good, contrasting it to laissez-faire approaches:

The revival of attention to these things [mass ritual and art] is, I believe, a source of strength to the authoritarian states of Russia, Germany and Italy and a genuine gain to them, just as a lack of it is a source of weakness to the democratic societies of France, the United States and Great Britain. In so far as it is an aspect—and it partly is—of an aggressive racial or national spirit, it is dangerous. Yet it may prove in some measure an alternative means of satisfying the human craving for solidarity.86

Other articles in the issue were submitted by representatives from Russia, the Reichkultur in Germany, and from France, represented by the leftist intellectual Georges Duthuit. Despite approving the funding increases of the de Monzie ministry, Duthuit said that more could be done and pointed to the formation of La Maison de la Culture, the headquarters of Louis Aragon and Vaillant-Couturier’s Association des écrivains et artistes révolutionnaires.87 Duthuit specified that the organization’s mission was unique because it did not support artists through the purchase of bourgeois canvases displayed at salons but instead encouraged the sponsorship of art for initiatives that would speak more directly to the public, its goal being “to put constant pressure upon public authorities in order that the building and decoration of places destined for vast public galleries shall be entrusted to those whose work is, to use a now consecrated expression, representative of living art.”88

Turning their gaze toward national support systems, a French Left that had once upheld total liberty instead of state intervention now looked to the USSR and socialist realism for direction. For instance, if the contributors to Commune had once expressed an ambivalence about the state’s role in artistic production, by 1934 Vaillant-Couturier would praise the “extraordinary literary and artistic flourishing of the USRR” and point to the creation of a self-produced “proletarian culture” that “shatters the hypocritical slavery of neutrality in art” and provides a clear and well-defined position for the artist within the fabric of the state: “the poet has his place in the proletarian cité, where the painter, sculptor and architect have entire cities at their disposal for their studios.”89

On the right, pundits looked abroad to Fascist Italy, where they witnessed what they believed to be a spiritual revival of the arts beyond the scope of a market-based system. In the reactionary populist weekly Je suis partout, Charles Kunstler praised the structured syndicalist system of the Fascist Party for the links it forged between the artist, the state, and the people.90 For the Parisian art critic Waldemar George, a follower of Mussolini, Fascism provided both a set of standards and a license for freedom of expression without lapsing into the monotonous single style of the monarchic model:

The Italian state has forged an ethic, and its art shows its imprint directly and indirectly. It has extirpated the virus of determinism and materialism. It has brought back the sentiment of dignity and creative work to men, the love of objects, the taste for what is stable. It has inculcated them to the cult of intrinsic effort for its own sake. Here is how the state has been able to act upon art, considered a vital function.91

George’s Italophilic position on the arts in Italy sits easily with much of the so-called nonconformist cultural discourse of the 1930s, which synthesized Maurrassian thought with antimaterialist vitalism. Another opponent of artistic independence was Thierry Maulnier, a Nietzschean Maurrassian who sought to reinvigorate a stagnant democratic culture of individual liberties through an aristocratic and virile “humanism”:

The present-day state of our arts confirms for us the lesson of sociology, of politics, of our every-day experience. Democracy and capitalism are two malignant sides of the same political and economic coin. The dictatorship of these two false elites, neither with any taste, without any responsibility, without any art… Under this hideous democracy, radical or liberal, the reign of the merchant and the politician will enable the triumph of a vulgarity that was non-existent two centuries ago, and that we will only rid ourselves of with great difficulty.92

Reviewing the last Indépendants before the war in the deeply conservative establishment journal Beaux-arts, George launched one final attack on the Indépendants, as if he were kissing it off forever. “The Salon of Signac,” he wrote, “epitomizes the crisis of contemporary art.” He then offered up a position that few would disagree with: “mediocrity… cannot be the price of liberty.”93

Conclusion: A Purgatory for Success

The idea of a salon libre and the associated debates it provoked on the concept of artistic autonomy and independence had, from the time of the French Revolution, provided an occasion to reimagine the artistic and the political sphere and a platform through which to explore the tensions and incongruences that unite and divide the political and aesthetic realms. Sadly, in a period of cultural anxiety marked by fear, xenophobia, nationalist sentiment, and, ultimately, the threat of war, the ideals embodied in the Indépendants appeared as quaint and naive as Rousseau’s painting.

Regardless of its incontrovertible place in art history as a site for the emergence of modernism, in the last two decades of the Third Republic, the Indépendants had lost its value for all but the most devoted critics. These were the writers at L’Humanité, who, out of principle, consistently defended the institution until the start of the war. Despite noting that it remained one of “the most stunning in its repetitions and puerilities, the most tiresome in its abundance,” and despite conceding to the extreme “respite” of revelatory submissions, in 1937 L’Humanité’s George Besson insisted upon the principle of the institution, arguing that it was “the only [salon] that is not useless.” He urged patience to his readers, writing that if any “modern masters” were to emerge, it would be within its walls: “If these [masters] must emerge, it will be nowhere else but at the Indépendants, the bedrock of originality. The salon of Signac remains and will long remain the only purgatory for success.”94

- 1 All translations are my own unless otherwise noted. The lion protecting a voting urn was a symbol of universal suffrage. See for instance, Republican artist Charles Nègre’s sculpture Le suffrage universel, exhibited in the salon of 1849. The symbol was concretized in Léopold Morice’s statue of a lion guarding an urn of ballots on the pedestal of the Monument à la République, erected in 1883. See Maurice Offerlé, “Les figures du vote,” Sociétés & Représentations, vol. 12, no. 2 (2001), 108–30.

- 2 Jean Monneret, Les Artistes Indépendants: La conquête de la liberté artistique, 100e Exposition de la Société des Artistes Indépendants (Paris: Grand-Palais, 1989), 14.

- 3 The only requirement for admission was a small fee and that the work not be considered “obscene.”

- 4 The Indépendants was in fact more egalitarian than the Third Republic because women were permitted to display works of art and to vote in the election of the organizing committee. Women’s suffrage in France occurred only in 1944. On immigration policies, see instance James Lehning, To Be a Citizen: The Political Culture of the Early Third Republic (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2011).

- 5 Besides the “Exposition de Mai,” which took place annually outside on the Place Dauphine on a single day for two hours only, no public exhibition existed for artists outside the confines of the Academy. See Colette Caubisens-Lasfargues, “Le Salon de la peinture pendant la Révolution,” Annales historique de la révolution française 33 (1961), 193.

- 6 Numerous histories of aesthetic modernism relate the phenomenon to the expansion of political franchise. See, for instance, Jacques Rancière, The Politics of Aesthetics (London: Bloomsbury, 2013). “L’égalité des droits qui fait la base de la Constitution a permis à tout citoyen d’exposer sa pensée; cette égalité légale doit permettre à tout artiste d’exposer son ouvrage; son tableau, c’est sa pensée; son exposition publique, c’est la permission d’imprimer.” Rapport du Comité de constitution, August 21, 1791, cited in Caubisens-Lasfargues, “Le Salon de la peinture pendant la Révolution,” 197.

- 7 Quatremère supported the idea of a freely entered salon where artists used their judgment to determine the subject matter and style of their submissions, while also arguing that a disinterested public, not a coterie of academicians, would provide the most virtuous aesthetic judgment. See Yvonne Luke, “The Politics of Participation: Quatremère de Quincy and the Theory and Practice of ‘Concours Publiques’ in Revolutionary France: 1791–1795,” Oxford Art Journal, vol. 10, no. 1 (1987), 19. On the politicized issue of “public” judgment, see William Hauptman, “Juries, Protests and Counter-exhibitions before 1850,” Art Bulletin, vol.67, no. 1 (1985), 96, 99.

- 8 With each attempt to grant democratic representation in the arts (for males), “sharp critical reactions to the number of mediocre works” would invite the reimposition of judges. Though the revolutionary salons of 1791 and 1793 were more or less open, the prevalence of unsatisfactory works compelled the creation of a jury in all but name, the “Comité des Arts,” which rejected sixty-five works for the salon of 1795. In 1798 an official jury was named, but this was done away with for the salon of 1799, only to be reimposed in 1800. Excepting the fleeting revolutionary salon of 1848, the salon libre faded from memory while the First Empire, the Restoration, and the Second Empire saw the return of ancien régime hierarchies.Hauptman, “Juries, Protests and Counter-exhibitions,” 96.

- 9 For an overview of the discourses linking political representation and salon admission in 1848, see Neil McWilliam, Dreams of Happiness: Social Art and the French Left, 1830–1850 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1993). See also Hauptman, “Juries, Protests and Counter-exhibitions,” 96.

- 10 Nicholas Green, “‘All the Flowers in the Field’: The State, Liberalism and Art in France under the Early Third Republic,” Oxford Art Journal, vol.10, no. 1 (1987), 71, 76.

- 11 What remained of the former salon would be renamed the Salon des Artistes Français, reformed now with an elected jury that would inspire Ferry to compare its “universal suffrage” and “just governance” to the new Third Republic. However, in practice, pompiers who had served before remained on the juries of each Salon des Artistes Français, quickly perpetuating the exhibition’s reputation as a vestige of absolutism. See Jules Ferry, opening remarks, transcribed in Société des Artistes français, Livre d’or de Salon de la peinture et sculpture, vol. 3 (Paris: Libraire des bibliophiles, 1981), 127. For more on the democratization of the official salon and the creation of a “Republic of Arts” in artistic administration to match state governance structures, see Patricia Mainardi, The End of the Salon: Art and the State in the Early Third Republic (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1993); and Fae Brauer, Rivals and Conspirators: The Paris Salons and the Modern Art Centre (Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2013), esp. 67–106.

- 12 The presence, on opening day, of President of the Republic Jules Grévy, the director of fine arts, the prefect of the Department of the Seine, and the president of the municipal council provided a de facto stamp of approval for the event. See Mainardi, The End of the Salon, 134. Regarding the support of the Ville de Paris, see Monneret, Les Artistes indépendants, 14–16. Transcripts of Conseil Municipal discussions surrounding whether to provide support in the form of a venue for the December 1884 exhibition of the Indépendants are excerpted in Pierre Angrand, Naissance des Artistes Indépendants, 1884 (Paris: Nouvelles éditions Debresse, 1965), 71–75. It was also a means of diffusing the political tensions that had emerged with the selective salons. For more on the utility of cultural democratization, see Emmanuelle Loubat, “L’égalité dans la limite de l’utilité: Jules Ferry et la démocratisation de l’art (1879–1883),” French Historical Studies, vol. 40, no. 1 (2017), 71–94. See also Albert Boime, “The Salon des Refusés and the Evolution of Modern Art,” Art Quarterly 32 (1969), 1–26.

- 13 Universal suffrage (again for males) was established first in the constitution of the convention of 1793–1795 and then briefly in 1848 during the Second Republic. On the history of universal suffrage in France, see Pierre Rosanvallon, Le sacre du citoyen (Paris: Gallimard, 2001). On Republican cultural politics, see Vincent Dubois, La politique culturelle: Genèse d’une catégorie d’intervention publique (Paris: Belin, 1999). However, these values were never fully realized, and the rights of women and those in French protectorates and colonies were woefully, hypocritically ignored. For more on the double standards of the French Third Republic, see Gary Wilder, The French Imperial Nation-State: Negritude and Colonial Humanism between the Wars (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005); and Alice Conklin, Mission to Civilize: The Republican Idea of Empire in France and West Africa, 1895–1930 (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1997).

- 14 In 1920 a new committee permitted state purchases from the independent salons, including the Salon d’Automne, the Indépendants, and eventually the Tuileries. By 1923, the Indépendants was granted the status of a public utility, a permanent annual home in the Grand Palais, the right to receive monetary donations, and a seat for its president on the Conseil Supérieure des Beaux-Arts, a body directly answerable to the Ministry of Public Instruction and Fine Arts. See Toby Daniel Fortescue Norris, “Modern Artists and the State in France between the Two World Wars” (PhD diss., Northwestern University, 2005), 147–48. See also Claire Maingon, “Les salons du rappel à l’ordre, Paris 1914–1925: Des artistes français aux artistes indépendants” (PhD diss., Université́ Paris X-Nanterre, 2006), 116, 124.

- 15 The free salon also provided a symbolic arena to exercise one’s taste and opinion in an increasingly democratized public sphere, implicating the public as arbiters of taste contributing to the “construction of consensual truth” and “rituals of discursive judgment.” For more on these concepts, see William Ray, “Talking about Art: The French Royal Academy Salons and the Formation of the Discursive Citizen,” Eighteenth-Century Studies, vol. 37, no. 4 (2004), 528.

- 16 These histories of the salon reproduce, for the most part, the account already given in Gustave Coquiot, Les Indépendants: 1884–1920 (Paris: Librairie Ollendorff, 1921); and Pierre Angrand, Naissance des Artistes Indépendants. Scholarly discussions of the Indépendants, meanwhile, are fewer in number, limited chronologically, and not focused exclusively on the institution. While Patricia Mainardi’s The End of the Salon and Fae Brauer’s Rivals and Conspirators mention the Indépendants of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, only Dominique Lobstein’s introduction to the Dictionnaire des Indépendants is devoted exclusively to the subject, though this account stops in 1914. Dominique Lobstein, Le dictionnaire des Indépendants (Paris: L’Échelle de Jacob, 2004). See also Dominique Lobstein, “Un salon de Babel: La première exposition de la Société des artistes indépendants,” in La revue du musée d’Orsay 20 (2005), 38. More on the institutional context of the Indépendants can be found in Gérard Monnier, L’art et ses institutions en France, de la Révolution à nos jours (Paris: Gallimard, 1994); and Pierre Vaisse, La Troisième République et ses peintres (Paris: Flammarion, 1995). Scholarship on the salon of the interwar period can be found in surveys of interwar art such as Christopher Green’s. The most comprehensive treatment of the Indépendants during the interwar period is Maingon, “Les salons du rappel à l’ordre.” See also Malcolm Gee, Dealers, Critics, and Collectors of Modern Painting: Aspects of the Parisian Art Market between 1910 and 1930 (New York: Garland, 1981).

- 17 Totalitarianism is the term given in Coquiot, Les Indépendants, 2.

- 18 The salon’s founders include Albert Dubois-Pillet, a military man, traditional painter, and Freemason; Odilon Redon, the consummate outsider; and the self-proclaimed anarchist Paul Signac. Though the creation of the Société des Artistes Indépendants in 1884 predates the avowal of anarchist ideas by Signac, his open affiliation with anarchism can be dated to 1888, the year he befriended the anarchist publisher Jean Grave. His leadership of the salon until his death in 1935 forcibly colored critical impressions of it as an institution. See Robert L. Herbert and Eugenia W. Herbert, “Unpublished Letters of Pissarro, Signac, and Others,” Burlington Magazine, vol. 102, no. 692 (1960), 472–82, and no. 693 (1960), 517–22. See also Eugenia Herbert, The Artist and Social Reform: France and Belgium, 1885–1898 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1961); and Robyn Roslak, Neo-Impressionism and Anarchism in Fin-de-Siècle France: Painting, Politics and Landscape (Aldershot, UK: Ashgate, 2007).

- 19 On the fauves and on the 1911 showing of cubists in room 41, see Christopher Green, Art in France, 1900–1940 (Yale University Press: 2000), 15, 20; and Maingon, “Les salons du rappel à l’ordre,” 305. For more on the “Coup de Cubisme,” see Fae Brauer, “One Friday at the French Artists’ Salon: Pompiers and Official Artists at the Coup de Cubisme,” in Academics, Pompiers, Official Artists and the Arrière-garde: Defining Modern and Traditional in France, 1900–1960, ed. Natalie Adamson, Toby Norris, and College Art Association of America (Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars, 2009).

- 20 On the institutional conditions for the emergence of modernism and the Salon des Indépendants, see Thierry De Duve, “Why Was Modernism Born in France?,” Artforum, vol. 52, no. 5 (January 2014), 190–97, 234–35.

- 21 See Luke, “The Politics of Participation,” 18.

- 22 Maurice Denis, “Sur l’exposition des Indépendants,” La grande revue 48 (April 1908), 545.

- 23 Walter Benjamin, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” in Illuminations: Essays and Reflections, ed. Hannah Arendt, trans. Harry Zohn (New York: Schocken Books, 1969), 217–51.

- 24 Early reviews are so removed from political considerations that the editorial line of a journal provides little indication of how the journal’s critic will react. The aesthetic freedom of the Indépendants would test the boundaries of leftist critics such as the anonymous 1884 reviewer for Le Radical who, despite his desire to support a salon whose modus operandi matched his journal’s slogan (“liberty in all things”), urged the creation of “a commission” to ensure that certain “elementary conditions” were met and that the work not be “terribly licentious.” Le Radical, December 19, 1884, cited in Angrand, Naissance, 93. The critic was surely unaware of article 21 in the statutes of the Société, banning works that “threaten public morality.” See Lobstein, Dictionnaire, 26.

- 25 Roger Marx, “Le Salon des Artistes Indépendants,” La chronique des arts et de la curiosité, March 28, 1903, 102.

- 26 Gertrude Stein, Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas (New York: Literary Guild, 1933), 18.

- 27 Guillaume Apollinaire, L’Intransigeant, March 18, 1910.

- 28 Initially a socialist publication, it would become the organ of the French Communist Party in 1920.

- 29 Gustave Rouanet, “Le salon des Indépendants,” L’Humanité, April 14, 1905, 2.

- 30 Henry Revers, “L’exposition des Indépendants,” La revue des beaux-arts, March 24, 1907, 1.

- 31 Marx, “Le Salon des Artistes Indépendants,”102.

- 32 Roger Marx, “Le Salon des Artistes Indépendants,” La chronique des arts et de la curiosité, April 1, 1905, 99.

- 33 “L’esprit humain qui décide, le fait en vertu de l’opération intérieure de ce choix personnel appelé jugement, et qui suppose l’appréciation de la qualité des partis mis en présence… cette opération reste, en elle-même et dans ses effets, infiniment supérieure à la combinaison toute mécanique par laquelle, dans un conseil des chefs de parti ou dans une assemblée du peuple, quelque avis l’emporte sur l’avis opposé… Le procès démocratique est celui de la mécanique pure.” Charles Maurras, L’action française, November 27, 1915, 1.

- 34 “L’indépendance de l’art qui leur est si véritablement chère, ne se trouvera que dans l’anarchie, où, d’après l’expression si juste de Renou, ‘la moindre règle paraît un attentat à la liberté.’” Henry Lapauze, Procès-Verbaux de la Commune générale des arts, de peinture, sculpture, architecture et gravure (18 juillet 1793—tridi de la 1re décade du 2e mois de l’an II) et de la Société populaire et républicaine des arts (3 nivôse an II–28 floréal an III) (Paris: J.E. Bulloz, 1903), lxxvi. The Action Française excerpts are in Henry Mazet, ed., “Les arts et la Révolution (II),” L’action française, vol. 7, no. 134 (1905), 135. See also Henry Mazet, ed., “Les arts et la Révolution (I),” L’action française, vol. 7, no. 133 (1905), 65–72.

- 35 “Ils apercevaient en toute évidence sur le domaine de l’art, ce qu’on ne devait pas découvrir de sitôt sur le domaine politique: à savoir que la tyrannie d’une foule ignorante est autrement oppressive que l’oligarchie d’une élite, et conduit, fatalement, du reste à l’autocratie.” Lapauze, Procès-Verbaux, lxxvi.

- 36 “La mort de nos arts français sont les conséquences certaines de l’individualisme révolutionnaire et qu’il y a une condition première a une renaissance français sans laquelle les autres ne sont rien: la restauration du pouvoir royal.” Mazet, “Les arts et la Révolution (II),” 137.

- 37 “‘L’indépendance’ c’était la vielle idée quatre-vingt-neuviste et quarantuitarde, idée purement négative, qui, dans le domaine des arts et des lettres, comme dans les autres, n’a conduit qu’à la stérilité.” Maurice Pujo, “Aux ‘Indépendants,’” L’action française, May 1, 1908, 1.

- 38 For more on the connections between Mithouard and Denis, see Neil McWilliam, “Memory, Tradition and Cultural Conservatism in France before the First World War,” Art History, vol. 40, no. 4 (2017), 724–43; and Neil McWilliam, Une esthétique de la réaction: Tradition, identité et arts plastiques en France c. 1900–1914 (Dijon: Les Presses du réel, forthcoming).

- 39 “Les Indépendants ont fait depuis vingt-trois ans une expérience complète et concluante de la démocratie. Tout ce qui peut prétendre au titre d’œuvre d’art y a été exposé librement, égalitairement. Ça été le triomphe de ce que Adrien Mithouard appelé le numérisme: système d’individualisme absolu, de nivellement mathématique où les individus et les œuvres sont considérés comme exactement égaux et interchangeables, comme des unités équivalentes… C’est pourquoi on a été jusqu’à supprimer les groupements par école ou par sympathie. Oui, l’expérience a été rigoureuse. Le résultat maintenant apparait. La théorie de la porte large substituée à la porte étroite des anciens jurys a favorisé surtout l’envahissement, la mise en lumière des médiocrités.” Denis, “Sur l’exposition des Indépendants,” 545.

- 40 “Par définition le suffrage universel est contraire aux arts qui ne peuvent être livrés au jugement de la foule incompétente et fantasque.” Philippe Besnard, La politique et les arts (Paris: Librairie Académique Perrin, 1935), 6. Philippe’s father, Albert Besnard, benefitted from many Republican commissions during his lifetime, including the ceiling of the Grand Palais, home of the Indépendants.

- 41 Cited in Pierre Rosanvallon, Le sacre du citoyen: Histoire du suffrage universel en France (Paris: Gallimard, 1992), 452.

- 42 Coquiot, Les Indépendants, 6.

- 43 Guillaume Apollinaire, “Le Salon des Indépendants (III),” L’Intransigeant, March 20, 1910.

- 44 See Maingon, “Les salons du rappel à l’ordre,” on the end of the glory days of the salon.

- 45 Anonymous, L’Art et les artistes, April 1919, 1.

- 46 On the number of works permitted, see Maingon, “Les salons du rappel à l’ordre,” 116. The exhibitors numbered 1,141 in 1920, 1,700 in 1924, and 2,400 in 1928 (a number surpassed only in 1980). Ibid., 309n943, 312. On the international market for French modernism in the early twentieth century, see Gee, Dealers, Critics, and Collectors of Modern Painting, 14.

- 47 “C’est encore Dimanche, il rentre, calme et digne, / Comme si il revenait de pêcher à la ligne, / Ayant, dans le beau soir qui sent l’apéritif, / L’âme ingénue et la ferveur d’un Primitif!” Léo Larguier, “Le peintre du Dimanche,” L’art vivant, vol. 5, no. 1 (September 1929).

- 48 “Nous n’avons pas à nous occuper si on expose chez nous de la bonne ou de la mauvaise peinture, nous ne voulons être que des administrateurs.” Paul Signac, “Les incidents des Indépendants,” Paris-Journal, November 30, 1923, 4.

- 49 Armand Vallée, “Tout le monde aux Indépendants,” La vie parisienne, January 31, 1925.

- 50 This is described in detail in Beatrice Joyeux-Prunel, Nul n’est prophète en son pays? L’internationalisation de la peinture des avant-gardes parisiennes (1855–1914) (Paris: N. Chaudun / Musée d’Orsay, 2009).

- 51 Anonymous, Comoedia, March 23, 1912, cited in Lobstein, Dictionnaire, 56.

- 52 Georges de Céli,Le monde illustré, March 23, 1912, cited in Lobstein, Dictionnaire, 56.

- 53 On artistic nationalism in the interwar salons, see, for instance, Maingon, “Les salons du rappel à l’ordre,” 21; and Eugen Weber, The Hollow Years: France in the 1930s (New York: Norton, 1994), 87.

- 54 Monneret, Centenaire, 135; and Maingon, “Les salons du rappel à l’ordre,” 309n943, 312.

- 55 Romy Golan, Christopher Green, Éric Michaud, Beátrice Joyeux-Prunel, and others have explored how xenophobia and antisemitism manifested themselves within the specialized sphere of art criticism during this period. See Romy Golan, Modernity and Nostalgia: Art and Politics in France between the Wars (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995); Green, Art in France; Éric Michaud, “Un certain antisémitisme mondain,” in L’école de Paris, 1904–1929: La part de l’autre (Paris: Musée d’art moderne de la ville de Paris, 2000), 407; and Joyeux-Prunel, Nul n’est prophète en son pays?

- 56 “Le but sincère d’apporter un intérêt nouveau à l’exposition,” was how the artist André Léveillé, who proposed the change, had described it. See the Compte-rendu de l’assemblée générale des Artistes Indépendants, November 10, 1923, in Archives Societié des Artistes Indépendants, quoted in Maingon, “Les salons du rappel à l’ordre,” 311. Maingon’s archival research shows that the demand for this change in hanging was likely inspired by the request of an American artist named Guillaume Lerolle, who may have written to Signac and other salon directors requesting the change. For more on this change to the Indépendents see Golan, Modernity and Nostalgia, 139.

- 57 See Le bulletin de la vie artistique, December 15, 1923, January 1, 1924, January 15, 1924, and February 1, 1924.

- 58 Yves Alix, “La querelle des ‘Indépendants’: Une enquête I,” Le bulletin de la vie artistique, January 1, 1924, 12. See the responses by foreign artists in the second part of this inquiry, “La querelle des ‘Indépendants’: Une Enquête II—Chez les Artistes étrangers,” Le bulletin de la vie artistique, January 15, 1924, 29–48.

- 59 Guillaume Janneau, “La Querelle des ‘Indépendants,’” Le bulletin de la vie artistique, December 15, 1923, 519.

- 60 For more on the ambivalences of Republican universalism, see Mary Dewhurst Lewis, The Boundaries of the Republic: Migrant Rights and the Limits of Universalism in France, 1918–1940 (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2007).

- 61 Ibid., 75, 158.

- 62 For example, that April, the Fascist Thierry Maulnier, writing in La revue française, complained that too much attention had been paid to the “anti-Semitic persecutions” in Germany, while the antisemitic newspaper publisher François Coty had also requested in March that the government divide the German refugees into “de-concentration” camps to prevent their critical massing. Thierry Maulnier, “La révolution aristocratique,” La revue française, April 25, 1933, 541–42, quoted in Paul Mazgaj, Imagining Fascism: The Cultural Politics of the French Young Right, 1930–1945 (Newark, DE: University of Delaware Press, 2007), 117; and François Coty, “Camps de déconcentration?,” Figaro, March 8, 1933, 1.

- 63 Timothy P. Maga, “Closing the Door: The French Government and Refugee Policy, 1933–1939,” French Historical Studies, vol. 12, no. 3 (1982), 428, quoted in Lewis, Boundaries of the Republic, 175.

- 64 “Envahi par la vermine juive et le chromo à trois francs comme la crapuleuse foire aux chiffons de la Porte Montmartre.” Lucien Rebatet, La revue universelle 59 (October–December 1934), 503.

- 65 “Encore trop d’exemples de cette gangrène juive qui décompose forme et couleurs dans la suie ou l’orgeat.” Ibid.

- 66 “la plus salubre politique… Dans toutes les salles, d’ailleurs, les étrangers ont abandonné du terrain. S’est sans doute une des causes de l’air d’unité et de simplicité du Salon.” Ibid.

- 67 See Malcolm Gee’s analysis of this problem in Dealers, Critics, and Collectors of Modern Painting.

- 68 Interview with Paul Signac, Paris-Journal, November 30, 1923, cited in Gee, Dealers, Critics, and Collectors of Modern Painting, 16.

- 69 Lobstein, Dictionnaire, 67.

- 70 “Car voici le mal de l’époque… On voit bien au Salon des Indépendants, plus enfoncé que jamais dans la gluante médiocrité. La preuve même de la décadence de ce Salon nous est offerte par le public dont la satisfaction, cette année est visible. Car l’art véritable a toujours été un attentat au goût du nombre.” Jacques Guenne, “Jour de fête: A propos du Salon des Indépendants,” L’Art vivant, February 1, 1925.

- 71 Anonymous, “Le Salon des Indépendants,” L’Art vivant, February 1, 1929.

- 72 Jacques Memmi, “Le 38e Salon des Indépendants,” L’Humanité, January 22, 1927, 3.

- 73 The journal carefully followed the thought of Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels, and Vladimir Lenin, often excerpting portions of these authors’ works, including their positions on the subject of fine art. In an article of 1933 Jean Fréville interpreted their writings to assert that within a communist society there were no painters but simply men who “occupy themselves with painting.” Jean Fréville, “Marx et la littérature,” Commune, vol. 1, no. 6 (October 1933), 262.

- 74 Camille Mauclair, “Les mercantis du temple,” Figaro, June 28, 1928. See also the parallels in Nazi art criticism; for instance, Wolfgang Willrich, Säuberung des Kunsttempels: Eine kunstpolitische Kampfschrift zur Gesundung deutscher Kunst im Geiste nordischer Art (Munich: J.F. Lehmann, 1937).

- 75 Camille Mauclair, L’art indépendant français sous la Troisième République: Peinture, lettres, musique, Bibliothèque internationale de critique (Paris: Renaissance du Livre, 1919), 39–40.

- 76 Camille Mauclair, La farce de l’art vivant (Paris: Editions de la Nouvelle Revue Critique, 1929), 201.

- 77 Besnard, La politique et les arts, 6.

- 78 Gee, Dealers, Critics, and Collectors of Modern Painting, 283–85.

- 79 René Chavance and Marius Richard, “La peinture devant la crise,” Beaux-arts, March 1932, 6.

- 80 Raymond Cogniat, “Pour aider les artistes,” Beaux-arts, March 1933, 6.

- 81 Norris, “Modern Artists and the State,” 189; and Georges Pascal, “Paris aide les artistes,” Beaux-arts, January 1, 1933, 2.

- 82 This includes Le Groupement Syndicale des Artistes et Artisans d’Art and Le Syndicat de la Propriété Artistique (part of CTI, the Confédération des travailleurs intellectuels). See Charles Kunstler, “La grande pitié des artistes de France,” Beaux-arts, August 11, 1933, 6.

- 83 Ibid.

- 84 First, de Monzie collapsed the two-tiered exhibition committee into one commission consultative that would purchase contemporary art works from all the salons and take advantage of the low art prices during the crisis to ameliorate its collections. A twelve-person committee was also established and given a budget to purchase works for the Luxembourg museum, while a more agile subcommittee of five people worked to acquire works by living artists only. Norris, “Modern Artists and the State,” 149, 189.

- 85 For examples of Mauclair’s calls for reform, see Camille Mauclair, “L’art résolument moderne,” Figaro, September 18, 1930. See also Mauclair, “La réforme artistique de l’état,” Figaro, June 6, 1933. For more on the attempt by a coalition of Far Right leagues (e.g., Action française, Les Jeunesse Patriotes, Solidarité Française, and Les Croix de Feu) to overthrow the republic on February 6, 1934, see Robert Soucy, French Fascism: The Second Wave: 1933–1939 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995).

- 86 John Maynard Keynes, “Art and the State—I,” The Listener, August 1936, 374.

- 87 This and satellite organizations were integrated into Leon Blum’s Front Populaire administration one year later. For more, see Pascal Ory, La belle illusion: Culture et politique sous le signe du Front Populaire 1935–1938 (Paris: Plon, 1994).

- 88 Georges Duthuit, “Art and the State—III—France,” The Listener, August1936, 476.

- 89 Paul Vaillant-Couturier, “Avec qui êtes-vous artistes et écrivains?” Commune, vol. 1, no. 5–6 (January–February 1934), 484.

- 90 Charles Kunstler, Je suis partout, May 20, 1933.

- [91] Waldemar George, “La Quadriennale de Rome,” L’Art et les artistes, no.155, March 1935, 209.

- 92 “L’état actuel de nos arts ne fait que nous confirmer la leçon de la sociologie, de la politique, de notre expérience de tous les jours. La démocratie et le capitalisme ne sont que les deux faces économique et politique d’un même mal. La dictature de leurs deux fausses élites, l’une et l’autre sans gout, sans responsabilité, sans durée, celle du politicien et celle du marchand, a sur le destin des beaux-arts et des activités désintéressées les même redoutables conséquences. . . . La hideuse démocratie libérale ou radicale, le règne du marchand et du politicien on fait triompher en France une vulgarité que ce peuple ignorait il y a deux siècles et de laquelle il se délivrera difficilement.” Thierry Maulnier, “Un régime ennemi des arts,” Combat, vol. 1, no. 4 (April 1936).

- 93 “La liberté ne doit pas être une simple prime à la médiocrité.” Waldemar George, “Le Salon des Indépendants,” Beaux-arts: Chronique des arts et de la curiosité: Le Journal des arts, vol. 76, no. 324 (March 17, 1939), 1.

- 94 Georges Besson, “Salon des Indépendants,” L’Humanité, March 11, 1937, 8.