The Via della Conciliazione (Road of Reconciliation): Fascism and the Deurbanization of the Working Class in 1930s Rome

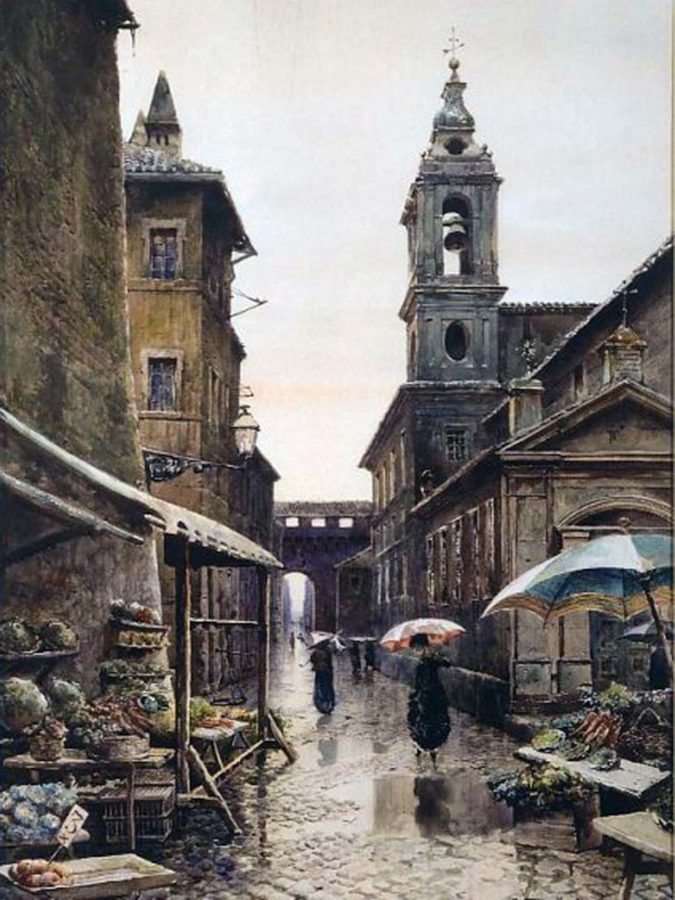

Visiting Rome in 1827, French writer Stendhal noted, “This morning, when our carriage crossed the Sant’Angelo bridge, we caught sight of St. Peter’s at the end of a narrow street. We followed this straight road and finally arrived at Piazza Rusticucci.”1 (Fig. 1) A contemporary visitor cannot recreate Stendhal’s sudden revelation as he encountered the gigantic basilica. Because of the destructive urban renovations carried out by Benito Mussolini’s Fascist regime, which displaced most of the area’s lower-income residents, the façade of St. Peter’s is no longer obscured but can now be seen in full view from many vantage points in the surrounding area of Rome. The ceremonial Via della Conciliazione, begun in 1936 and concluded in 1950, has replaced the lively streets and alleyways through which Stendhal traveled.

For centuries, however, the relationship between St. Peter’s Basilica, its square, and the adjoining neighborhood was an unresolved matter.2 When, in 1667, Gian Lorenzo Bernini presented his project for the piazza, a third wing of the colonnade was expected to close off the view and operate as an antechamber for the basilica, separating the space of devotion from that of commerce and other secular activities. (Fig. 2) This third freestanding colonnade was never built. In keeping with the baroque aesthetics of wonder and surprise, Catholicism’s holiest shrine was nested within a labyrinth of alleyways in an area called the Spina di Borgo (Spine of the Borgo). The approach to St. Peter’s was unexpected and theatrical, as pilgrims caught occasional glimpses of its gigantic dome before emerging into the dramatic light of the square, framed by the welcoming arms of the colonnade.

The Spina di Borgo comprised four irregular blocks in front of St. Peter’s that included buildings by Donato Bramante, Baldassare Peruzzi, Domenico Fontana, and Carlo Maderno, among other prominent Renaissance and baroque architects. The Spina di Borgo had grown after the 1527 sack of Rome as an extra line of defense. In the shape of a wedge, the area was located between the roughly parallel streets of Borgo Nuovo and Borgo Vecchio. (Fig. 3) If one stands with one’s back to the Tiber River, the Spina began with Piazza Pia, dedicated to Pope Pius IX (1846–1878). Halfway through, the Spina had another square, Piazza Scossacavalli, with, among other important buildings, the church of San Giacomo Scossacavalli (now demolished), the palace of the Torlonia family, and the Bramante-designed Palazzo Caprini (now demolished), where Raphael died. The basilica peeked through the narrow street Stendhal described, which ended in the Piazza Rusticucci, just outside the colonnade.

Despite the presence of aristocratic and religious palaces, most permanent residents of the Borgo belonged to the working class. The area was home to a belligerent population that was as likely to serve as to rebel against the pope. During the beleaguered unification process, Borgo residents sided with the Italian state rather than the church, voting in favor of the annexation of Rome in 1870.3 Painter Ettore Roesler Franz’s watercolors of “Vanished Rome,” made from 1878 to 1896, record the picturesque ambience of the Borgo. (Fig. 4) Its cobblestones, weathered buildings, and daily life activities gave it the quaint feeling associated with a preindustrial era.

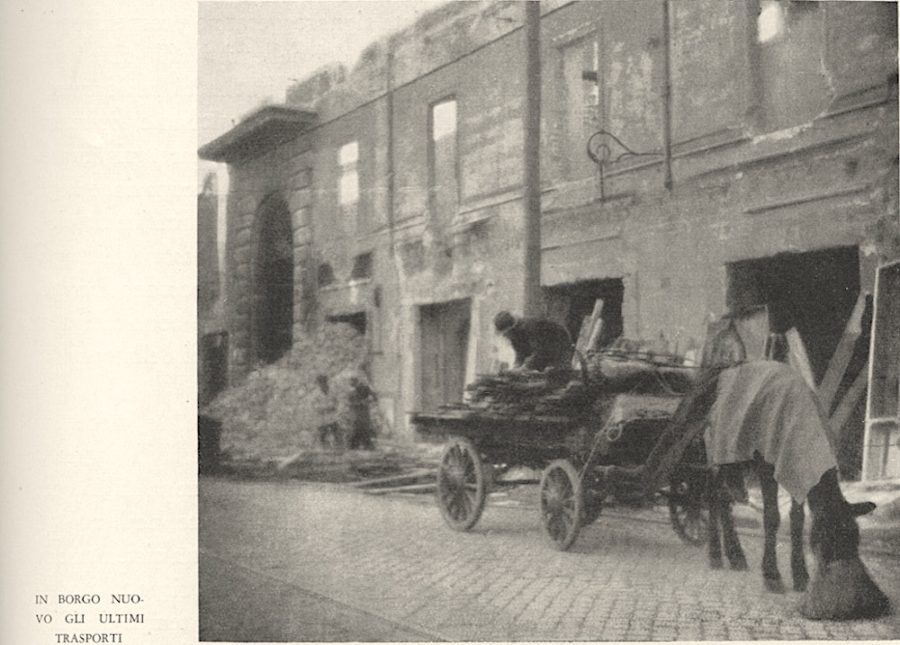

The Spina’s awkward layout had spurred proposals for its demolition since the seventeenth century, but such plans had never been executed.4 This changed on October 29, 1936, when work began on the Via della Conciliazione, or “Road of Reconciliation.” By October 8, 1937, the demolition of the Spina was complete.5 (Fig. 5) All that remained was an irregularly shaped void that increased in width toward the basilica. While systematic demolitions were a predominant feature of Fascist urbanism, the strategy was not novel.6 Sixtus V and Domenico Fontana’s baroque transformation of Rome, Baron Haussmann’s destructive remaking of Paris in the nineteenth century, and the construction of the Vittoriano, the intrusive monument to Victor Emanuel I in Rome’s Piazza Venezia, are notable precedents.7

Italian debates about whether to diradare (thin out) the urban fabric through selective demolitions or to entirely transform areas through large-scale razing had been animated since the 1890 founding of the Associazione Artistica fra i Cultori di Architettura (Artistic Association of the Appreciators of Architecture), an association of architects, painters, sculptors, and amateurs interested in archaeology and the protection and preservation of architecture, mostly in Rome.8 Yet sventramenti (literally, gutting or disemboweling) dominated the strategy of urban renovations under Mussolini’s regime. The indiscriminate razing of entire quarters was motivated by a desire for grandeur and ritualistic uses of urban space that celebrated the Fascist state and short-circuited the relationship between Fascist Rome and its heroic past.

The Via della Conciliazione was designed by Marcello Piacentini and Attilio Spaccarelli to celebrate the Lateran Accords between Italy and the Holy See. In 1934 the architects presented two diametrically opposed projects for this area to the governor of Rome, Prince Francesco Boncompagni Ludovisi, and to Mussolini, Italy’s prime minister since 1922.9 Spaccarelli’s proposal preserved the Spina (and was looked on favorably by the Vatican), while Piacentini’s proposal demolished it. In 1935, the two architects were asked by Giuseppe Bottai, the new governor of Rome, to collaborate and present a joint scheme. The new project—in which the Spina would be demolished but a colonnade gateway would separate St. Peter’s Basilica from the Via della Conciliazione—was approved by Mussolini and Pope Pius XI in June 1936.10 As proof of the new cordial climate between Italy and the Holy See, both Mussolini and Pius XI repeatedly visited the building site of Via della Conciliazione, framing it as a collaborative project rather than as a strictly “Fascist” one—although the street is not within the Vatican territory but in Italy, and Fascist ideas of urban planning profoundly shaped it.

The Via della Conciliazione was to be inaugurated in 1942 during the Universal Exhibition of Rome (or EUR 42). World War II caused the cancellation of EUR 42, and the postponement of restoration of the extant buildings of the Borgo and the construction of new ones along the Via.11 The postwar Italian Republic took on the task of finishing the restoration and construction project. To correct its varying span and at least make it seem as if both sides of the road were parallel, the Via della Conciliazione was flanked by a row of twenty-eight obelisk-shape streetlamps, replicas of the Vatican Obelisk in St. Peter’s Square.The streetlamps guide the eye toward the basilica, whose colossal scale can finally be appreciated but is also dwarfed by the long perspective. Because of its dimensions, the Via della Conciliazione is better designed for motor vehicle traffic circulation and routing the crowds of pilgrims visiting the Vatican than for everyday pedestrian activities.

The Via della Conciliazione celebrated the “Reconciliation,” which put an end to fifty years of hostilities between the Vatican and the Italian state. Despite its name, the Via della Conciliazione embodies conflicts between church and state, conservation and demolition, tradition and modernity.12 In this article, I move from an analysis of the built environment to one of the human effects of urban renewal, studying the Via della Conciliazione as an example of Fascism’s reshaping of Rome’s population along class lines. Although work on the Via della Conciliazione was interrupted during World War II and the road was not inaugurated until the jubilee year of 1950, its plan was developed in the context of the Fascist regime and embodies Fascism’s attitudes toward the working class and urban spaces.

A Symbol of the “Reconciliation” between Italy and the Holy See

In 1871, after the annexation of Rome to the Kingdom of Italy that ended his temporal rule over the city, the pope refused to recognize the newly united state and ensconced himself in the Vatican palaces. The papacy’s political independence could be assured by its ruling a civil territory, no matter how diminished. Italy, however, considered it nonnegotiable that Rome be the capital of the unified state. After the capture of Rome, succeeding popes took great care to disavow the legitimacy of the Italian government; for example, they refused the offer of an annual financial payment, did not set foot outside the walls of the Vatican, and forbade Catholics from participating in Italian elections. For its part, the Italian state systematically pursued anticlerical policies, confiscating a significant amount of church property and suppressing (or heavily taxing) many Catholic religious institutions.13

As a result, until 1929 Rome contained in its midst an antagonistic enclave—the space of a religious power with secular aspirations that was the spiritual leader of Italy’s majority Catholic population. This tension was often enacted in St. Peter’s Square itself, frequently the site of anticlerical demonstrations because of its charged history as the symbol of papal authority and then, during the Napoleonic wars and the 1848 Liberal Revolutions, as the stage of defiantly secular ceremonies.14 The animosity was such that when Pope Leo XIII ascended to the throne of St. Peter in 1878—the first pope to be elected after the Italian occupation of Rome—he gave his first apostolic blessing urbi et orbi not from the main loggia of St. Peter’s, as was the custom, but from inside the basilica.

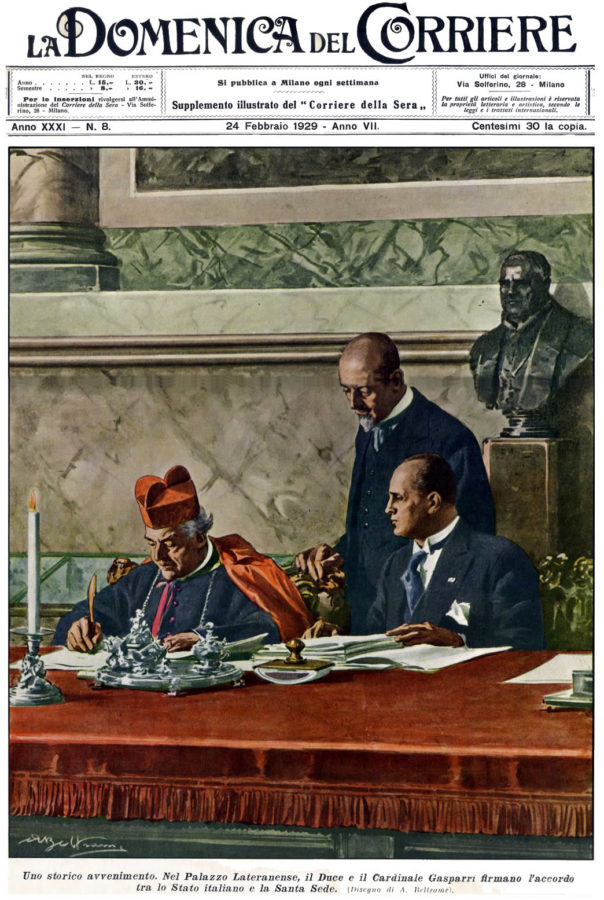

The signing of the Lateran Accords by Mussolini (on behalf of the Italian state) and Cardinal Pietro Gasparri (on behalf of the Holy See) on February 11, 1929, marked the end of hostilities. (Fig. 6) The pope agreed to maintain neutrality in international relations and to refrain from intervening in Italian internal affairs. Italy, in turn, recognized Catholicism as its official religion and agreed to follow church views on marriage and divorce. The Holy See received an economic indemnity for the loss of its territories, now restricted to the Vatican City State (an enclave of just 121 acres) and to some extraterritorial properties with tax privileges.

The Via della Conciliazione was a tangible manifestation of the mutual recognition of sovereignty and territorial demarcations between the Vatican and the Italian state.15 It also reshaped the role of St. Peter’s Square as a signifier of papal power: no longer an anticlerical space, it now would be exclusively reserved for religious celebrations. Yet, de facto, by making St. Peter’s visible from afar and no longer enclosed by the Borgo,the thoroughfare merged the Vatican with the rest of the city of Rome, bypassing the separation of powers that the Lateran Accords had established.

During the sixty years of tension between the Vatican and the Italian state, the Spina di Borgo was a buffer between secular and religious Rome. Piacentini and Spaccarelli initially wanted to respect this history—and pay tribute to Bernini’s original project—by preserving the separation between St. Peter’s and the rest of the city.16 In their original proposal, they had envisioned the construction of the third wing of Bernini’s original project. The nobile interrompimento (noble interruption) would physically separate the Vatican from the city of Rome. By the end of 1937, a life-size model of this new wing had been made, and photomontages of how it would look from the Via della Conciliazione were created.17 (Fig. 7)

Yet this part of the project was never realized, per ordini superiori (because of orders from above)—either by direct intervention of Mussolini or of the Vatican authorities, most likely the former.18 By eliminating this third wing and designing a major thoroughfare that would converge with the square, Piacentini and Spaccarelli made St. Peter’s Basilica fully visible from afar. The Via della Conciliazione thus effectively annexed the Vatican to the rest of Rome, fusing the spiritual city with the Fascist city.19

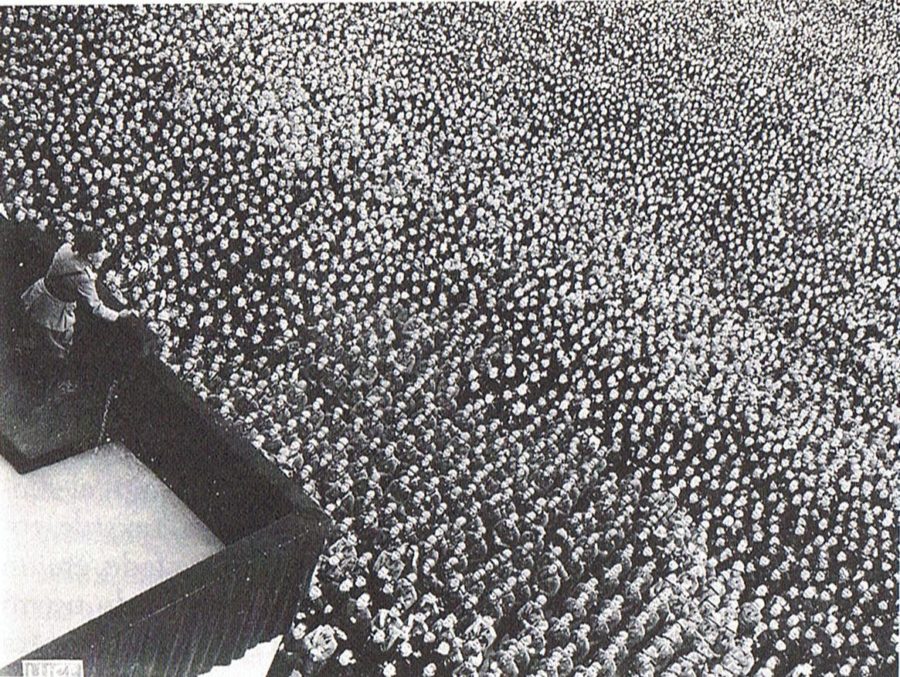

Piacentini and Spaccarelli designed the Via as a scenographic setting for St. Peter’s and as the site for opulent displays of authoritarian rule—part of the campaign to turn Rome into the monumental capital of the new Fascist empire. This justifies an analysis of the Via della Conciliazione as the embodiment of one of the pillars of the Fascist aestheticization of politics: the notion of spectacle.20 As Simonetta Falasca-Zamponi argues, “the prevalence of form over ethical norms… characterizes Italian Fascism’s aestheticized politics; and it is the emphasis on form (intended as appearance, effects, orderly arrangement) that helps to explain Fascism’s cultural-political development.”21 In Mussolini’s aesthetic reading of the politician’s task, Fascism’s mission was to give shape to people’s lives. The “fascistization” of Italy implied the construction of a homogenous population, through a unified style that gave coherence and distinctiveness to the way people talked, dressed, moved, lived, and so on. In this way, instead of a disjointed and uneven crowd, harmony and uniformity would prevail in the body politic: in Falasca-Zamponi’s words, “the ‘masses’ were at the same time part of the fascist spectacle and fascism’s spectatorship; they were acted upon and actors.”22 The scrutiny and modeling of behavior was supposed to achieve the transformation of the Italian character. The transformation was to penetrate from the surface to the core, from appearance to substance.

One of Mussolini’s main beliefs was that changes to urban geography and architecture would affect the ethical makeup of Italians. In 1924 he announced:

I should like to divide the problems of Rome, the Rome of the Twentieth Century, into two categories: the problems of necessity and the problems of grandeur. One cannot confront the latter unless the first has been solved. The problems of necessity rise from the growth of Rome, and are encompassed in this pair: housing and communications. The problems of grandeur are of another kind: we must liberate all of ancient Rome from the mediocre construction that disfigures it, but side by side with the Rome of antiquity and Christianity we must also create the monumental Rome of the Twentieth Century. Rome cannot, must not, be solely a modern city, in the by-now banal sense of that word; it must be a city worthy of its glory, and that glory must be revivified tirelessly to pass it on as the legacy of the Fascist era to generations to come.23

“Spectacle and surveillance,” “the twin pillars” of Fascist urbanism, in Diane Ghirardo’s words, have become a key interpretative framework for the study of the regime’s urban and architectural projects.24 Yet while spectacle-centered analyses explain Fascism’s interest in totalitarian control over the most exterior aspects of life, Il Duce’s regime did intervene, and profoundly, on core elements such as press censure, imprisonment of anti-Fascist intellectuals, persecution of dissenting voices, and displacement of potentially dangerous populations.

The Via della Conciliazione was not only an example of Fascist aesthetics of power but enacted one of Fascism’s most distinctive strategies: the systematic deurbanization of the working class. As architectural historian Paolo Nicoloso observes, the mid-1930s coincided with a moment of consolidation of the regime, when Mussolini viewed architecture and war as intertwining strategies for the formation of new Italians.25 I would like to complicate conceptions of Fascist urbanism in terms of the situationist-inspired notion of spectacle—with its evocation of performativity, theatricality, and ritual—with an analysis of the social effects of the transformation of Rome. Focusing not on the form of Fascist urbanism (spectacle) but on its content (the displacement of the working-class from the city center) helps us understand the concrete ways in which Fascist authority was enacted in the city space. This approach calls attention to the ways fear of class conflict shaped Rome’s built environment during the interwar period. It also unpacks how the transformation of Rome played a role in the construction of political consent and in the organization of the masses in interwar Italy.

Fascist Urbanism against “Local Color”

The construction of the Via della Conciliazione destroyed not only buildings but a thriving community. Yet this second destruction has rarely been portrayed visually—either in official photographs or in works by artists nostalgically representing the sections of Rome that Fascist urban projects destroyed. Mario Mafai’s Demolitions of the Borghi (1939, Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna, Rome), for example, reinterprets a series of photographs by Pietro Canton that record the geometric patterns of a building in Piazza Pia while in the process of being demolished. (Fig. 8) Yet, while Canton’s photographs show the Borgo as a lived space, with pedestrians, tramways, stores and their awnings, and clothes hanging from windows (fig. 9), Mafai depicts a spectral town, completely deprived of life, a ruin akin to Pompeii or Herculaneum. The unpeopled canvas dramatically articulates the human cost of Fascist urbanism and its class-based logic by refusing to depict the urban transformation of Rome in the heroic terms advanced by the regime.26

Fascist urbanism relied heavily on sventramenti, the destruction of existing buildings. The maneuver’s aim was to liberate ancient structures from successive additions and destroy the idea of Rome as a palimpsest of historical layers. The rhetoric of liberation was frequently deployed, with Mussolini claiming that “the millennial monuments of our history must loom gigantic in their necessary solitude.”27 Freeing buildings from later accretions operated as a metaphor for the relation between modern Italy and its heroic past, and between Italy and other nations. Like its ancient monuments, Fascist Italy would finally liberate itself from the ballast of the past and from its secondary position in international politics. The aim was not to erase history but to redefine it in heroic terms by selectively preserving iconic monuments and by opening thoroughfares that facilitated military parades and car circulation.28

Art historians and archaeologists, rather than architects and urbanists, were in charge of most Fascist urban projects—Piacentini’s and Spaccarelli’s involvement with the Via della Conciliazione was one of the few exceptions. Italian archaeologists, as urban historian Italo Insolera observes, had a “stylistic and monumental” conception of the past, in which only the isolated and major monument (e.g., the temple, the amphitheater, the palace) was held in high regard.29 The rhetoric of “necessary solitude,” in Mussolini’s words, operated not only for ancient Roman monuments—buildings that were the center of attention of Fascist urban planning—but also for St. Peter’s because of its iconic status.30 Isolation and monumentalization went hand in hand. Much as the Via dell’Impero (1932) or the Piazza Augusto Imperatore (1937) emphasized the Roman Fora or the Mausoleum of Augustus, respectively, by eliminating structures that had accrued over time and, in the latter case, by creating new ceremonial buildings, the Via della Conciliazione obliterated all the constructions that were considered less important than St. Peter’s, with the purpose of highlighting the basilica.

Sventramenti served no clear urban purpose. Rather, they were ideologically driven. They destroyed what, for architectural historian Leonardo Benevolo, was the marker of modern Rome: the “coexistence of the monumental scale and the ordinary scale.”31 Sventramenti created a visible, direct connection between modern and ancient Rome, encouraging Italians to behave as worthy heirs of their glorious past—above all through imperial wars and aggressive politics.

Sventramenti also systematically obliterated traces of low-income life in Rome. Fascist officials often described such vernacular architecture with the term colore locale (local color). Colore locale was the quaint Rome that foreign visitors loved but that also encouraged them to treat Italians in a patronizing way: “a Rome full of ruins, potholed pavements, scabby houses nestled against ancient monuments out of which grew grass,” one Fascist official wrote, with “barefoot ragged children, and donkeys carrying wood.”32 Colore locale, such as that lovingly represented by Roesler Franz, reinforced an idea of Italy as an unchanged, premodern country rather than the leading industrialized state that many believed the Fascist regime would bring to fruition.

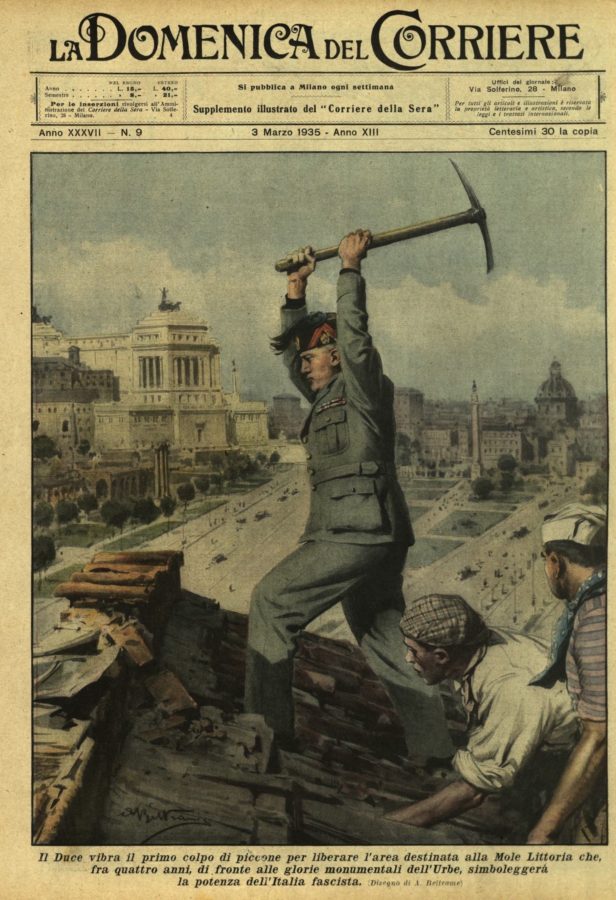

As Rome Governor Giuseppe Bottai stated in 1943, “We do not love colore locale. We are convinced of the absolute sterility of these artificial continuations of a way of life that no longer corresponds to life today.”33 The “grim picturesque” local color, Mussolini explained, had to be “taken care of by its Majesty the pickaxe” and “must vanish, in the name of decency, of hygiene, and of the beauty of the city.”34 (Fig. 10) Demolitions would wipe out this quaint Rome and transform the city into a majestic capital reflecting the new political stature of Fascist Italy. The rebirth of Italy as a nation had to be accompanied, in the Fascist mindset, by the rebirth of its capital.

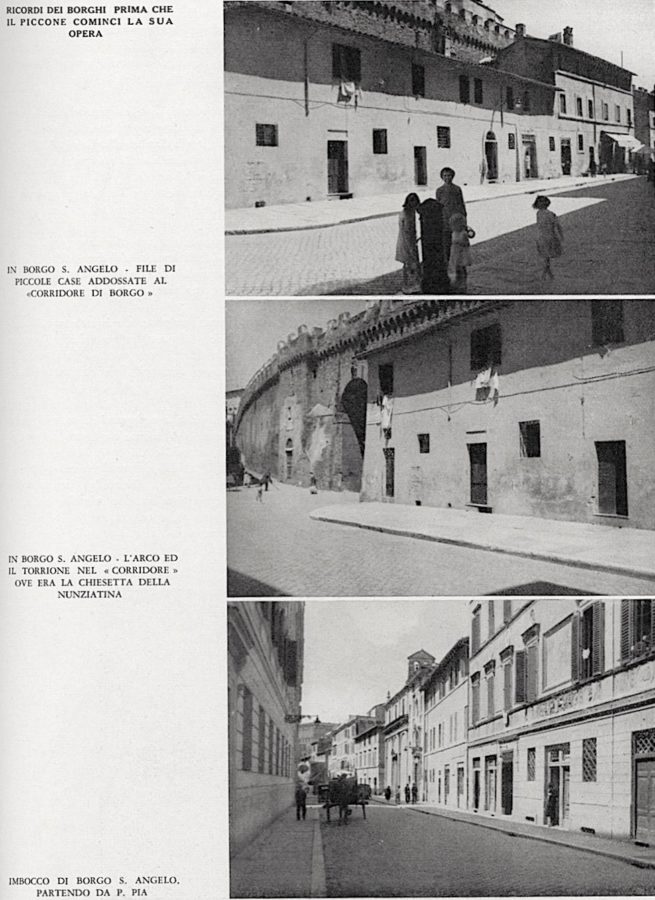

Urban historian Antonio Cederna observes how the language used in official communications reflects Fascism’s contempt for colore locale.Medieval and Renaissance quarters were described as shameful and unbecoming “shacks,” “shanties,” and “hovels.”35 Spaccarelli and Piacentini, too, dismissed the Spina di Borgo as nothing more than remnants of colore locale. They wrote in an article published in the journal of the Governatorato of Rome, “There is no reason for tearing down a neighborhood without a precise motive, either of aesthetics, traffic, or hygiene; but when it comes to sacrificing a very small amount of local color, to obtain perhaps the most beautiful architectural picture in the world, there is no doubt that such fears must disappear, as in fact, they have all completely disappeared.”36 In their articles and books about their project for the Via della Conciliazione, they were careful to include photographs of the Borgo that recorded only its most dilapidated and run-down buildings. (Fig. 11)

Not everyone was against colore locale, though. When the demolition of the Spina was first suggested, defenders of folklore and the picturesque published their views in local newspapers and specialized magazines. But their voices were soon drowned. For most Fascist officials and architects, colore locale represented a view of Italy developed by foreign tourists that perpetuated clichés about backwardness and poverty. By contrast, the “new Rome” was defined by self-representation; it no longer aspired to fulfill the expectations of foreigners but rather to express the dreams and desires of Italians themselves.

Borgate, “Ersatz Communities”

Spaccarelli and Piacentini’s project entailed the razing of 43,000 square meters of constructions. Medieval, Renaissance, and baroque palaces and churches were demolished or partially reconstructed in new locations.37 In addition to artistically and historically significant constructions, numerous residential buildings were destroyed.38

The Borgo, like many other areas of Rome, had mixed-use buildings, with homes and offices in the upper stories, and shops, bakeries, and restaurants on the ground floor.39 Writer Emilio Cecchi once more denigrated the concept of colore locale in an article entitled “Psychology of Demolitions,” arguing, “We do not really care about the little doorways, the little corners, the little courtyards, the little taverns, the boring history, the typical smell of sacristy” of the Spina di Borgo.40 Yet with the Via della Conciliazione an entire neighborhood disappeared, transforming forever the urban makeup of the area.

Such were the artistic and historical costs of the Via della Conciliazione.41 But what about its human costs? The construction of the Via destroyed a vibrant if stratified community. As was common in many areas of Rome, the palaces of the Spina were inhabited not only by their wealthy owners but by renters from other social classes. Surprisingly, Spaccarelli and Piacentini are among the few to have recorded the daily life of the Borgo. In a detailed article in which they presented their project, they included three photographs entitled “Souvenirs of the Borgo before the pickaxe begins its work.”42 One can see disheveled children collecting water at a public fountain while shop owners linger on the doorways of their stores. A modern car and a horse-drawn carriage share the street. A man with a crutch plays with a little boy. (Fig. 12)

A 1937 study commissioned by the city administration shows the heterogeneous class composition of the area. The vast majority of the residents were wage workers (operai salariati). Because of the Spina’s proximity to the Vatican, it also was home to a high number of white-collar workers, merchants, and members of religious orders and the liberal of white-of white-collar workers, merchants, and members of religious orders and the liberal professions.43 The demolition of the Spina forced 1,236 families, a total of 4,992 people living in 729 apartments, to relocate.44

And here the class politics of Fascist urbanism are clearly revealed.45 The relocation of the former residents of the Spina was starkly differentiated according to class.46 Because the owners of the demolished houses and shops received economic compensation for their losses, they acquired new lodgings of equal, if not higher, quality.47 Some middle-class renters were relocated by the government to nearby apartments within the city limits; for example, just across the Tiber River. Their lives were not completely destabilized by the construction of the Via della Conciliazione; in most cases their circumstances improved, as their new homes were of better quality than the ones they had in the Borgo.

By contrast, most low-income residents of the Spina were sent to the borgata Primavalle, outside the city limits. A resident of the Spina recalled the relocation to the borgata: “I still remember when the trucks came, with the Fascists who loaded us up with those few rags we had; my mother screaming and us kids, on the trucks, thought it was a holiday. It was a long journey that seemed endless. They made us get off at a place that was a few scattered little buildings and mud all over. They said the name of the place was Primavalle.”48 (Fig. 13) Primavalle was located nine kilometers west of Rome, in an isolated agricultural area and in close proximity to the military installation Forte Braschi, then the headquarters of the Italian secret services.

Borgate, subsidized neighborhoods developed in Rome’s outskirts throughout the 1920s and 1930s, became the new home for a majority of the city’s displaced low-income residents.49 The term borgate is difficult to translate. From the German burg (just like “the [Spina di] Borgo”), borgata literally means “hamlet” and, as such, originally refers to small settlements in rural settings. In the context of human displacement during Fascism, however, a borgata is a quite large satellite of a metropolis, “a section of the city that does not have the completeness and organization to be called a ‘neighborhood,’” as Insolera puts it; “a piece of the city in the middle of the countryside that is neither city nor countryside.”50 Spiro Kostof calls them “Ersatz communities” and “scraps of city,” their residents living between city and country and belonging to neither.51

In Rome, twelve borgate were created from 1930 to 1937 in the Ager Romanus, the rural area that surrounds the city. Although the quality of the construction was low and they were not included in the urban master plan of 1931, the borgate were created through institutional decisions by the Governatorato of Rome and the Istituto Autonomo Case Popolari (IACP; Autonomous Institute of Popular Housing). Originally, the borgate were built to accommodate the urban poor who lived in shacks throughout the city. After the regime began an intensive campaign of urban transformation, the borgate served to house low-income families who had lost their (rented) living quarters to the “healing pickaxe.”

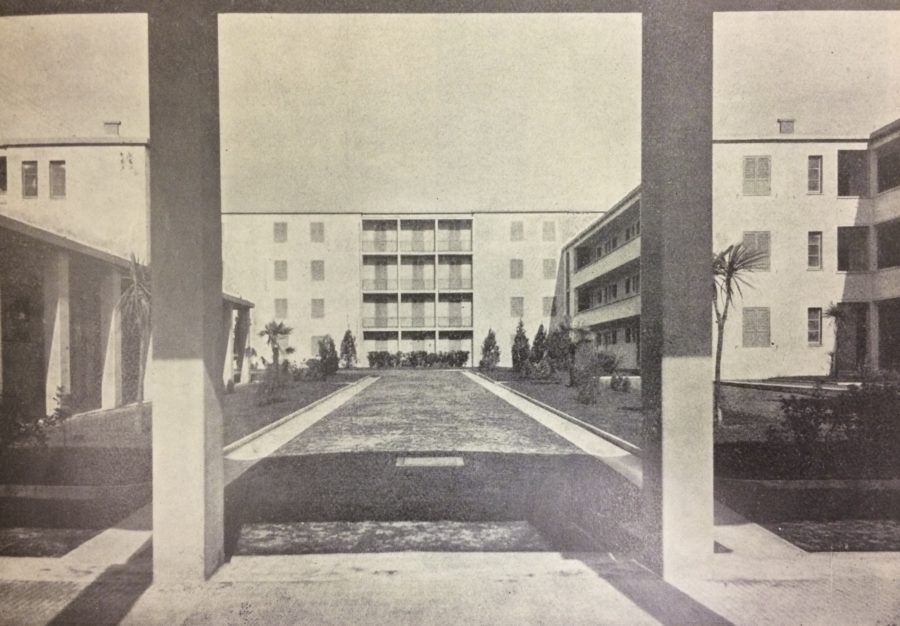

Primavalle, inaugurated in 1939 after two years of construction, offered former residents of the Spina some improvement in living conditions. Instead of cramped quarters, many residents now enjoyed relatively low-density housing with water in every house and communal gardens. Unlike the social stratification of the Spina, where the differences between the piano nobile (noble floor) and the rest of the house were sharply delineated, no class disparity was in evidence in Primavalle.52 The rationalist-inspired buildings had wide windows that allowed for air circulation and light.53 (Fig. 14) With their squared bodies and unadorned façades, they were homogenous and generic-looking. Yet they were easy to keep clean, and the whole area followed a logical plan that facilitated organization and circulation.54

Beyond those ostensible improvements to quality of life, however, the lack of social services and the location of Primavalle posed significant challenges for new residents. In other cities, dormitory neighborhoods or commuter areas served local industries, but Rome had little to none of the latter. Primavalle had no manufacturing facilities and only eleven shops for more than 500 apartments. Although more retail space was envisioned in its masterplan, it was hard to convince Roman shop owners to give up their profitable stores in the city and move to an area under construction and with low-income residents. Only Rome could offer employment. Yet Primavalle’s tenants, whose livelihoods had been based on providing services to wealthier Romans, had difficulty continuing to earn their living in the city. The cost, scheduling, and time of transportation now had to be considered, as the area was poorly connected to Rome.

Oral tradition insists that all the borgate sprang up as a direct result of the sventramenti in the city center. Yet urban historians Fernando Salsano and Luciano Villani have found that most residents of the borgate never lived in the areas affected by the demolitions but rather relocated there as the result of Rome’s housing crisis.55 Primavalle is an exception: it was the only borgata in which a majority of residents had been displaced as a consequence of the Spina’s demolition.

Pushing the Working Class to the Social Margins

While moves to the borgate were often presented as temporary, they were part of a systematic strategy to restrict migration to the cities and encourage exodus to the countryside. In 1928, Mussolini wrote that Rome’s housing problem could be solved only if “immigration into the city was hindered, and people were evacuated from Rome without pity.”56 But not all people, as the Spina di Borgo episode shows: only low-income residents were “evacuated,” thus reducing class stratification and leading to greater homogeneity among Rome’s remaining residents.

One of the first moves to achieve this homogenization—the liberalization of rents in the city—occurred in 1923, a year after the March on Rome. Rent prices had been restricted by previous liberal governments, which in turn facilitated internal migration from the provinces to the capital. Mussolini’s policy led to a rapid increase in the cost of living in Rome, forcing poorer emigrants to live in shantytowns and shacks.57 As Mussolini bragged in an interview with the New York Times in 1933, “in directing the population toward the hills and the sea we are clearing away all the unwholesome hovels, purging Rome, letting in air, light and sun.”58 By preventing the industrial development of Rome, Fascist urbanism rendered the difference between the bourgeois and the proletarian city ever more stark.

Whether because of the sventramenti or as a result of housing policies, the movement of the working class to the borgate was part of a Fascist strategy to encourage it to leave Rome. Borgate were not the byproduct of Fascist urban redevelopment but its goal—not consequence but cause. They were a system of social control, exerted through physical displacement and segregation. Located far from the city, they were also constructed far from one another in order to isolate their residents in easy-to-control neighborhoods.59 A 1930 report from the Governatorato of Rome underscores the necessity of transferring “workers and the unemployed, as well as families of irregular composition, of bad moral precedents… on land belonging to the Governatorato, in rural areas and hidden from the main roads… under the surveillance of a station of the Carabinieri or the Fascist Militia.”60 Like Primavalle, many borgate were built near military forts to better deter working-class protests or sedition.

In a country with a strong urban tradition, by 1921 almost 74 percent of Italians lived in urban centers.61 And urban centers were where Mussolini’s National Fascist Party first acted, occupying squares, exerting violence in the streets, and preventing political gatherings of rival factions.62 Fascism viewed cities negatively as seditious spaces abetting disobedience, class identity, and strife. The regime distrusted the uncontrolled public interactions that could take place in the city.63 Thus they presented cities as alienated spaces. Mario Sironi’s inhospitable cityscapes, for instance, show Milan as squalid and desolate, adverse to social relationships. (Fig. 15) For Sironi, Milan’s industrial development and fast-paced life were not thrilling but overwhelming.64

Influential Fascist intellectuals proudly affirmed an alleged rural identity. The Strapaese (ultra-village, ultra-local) group, for example—to which belonged the artists Mino Maccari, Ardengo Soffici, Carlo Carrà, and Ottone Rosai, as well as journalist Leo Longanesi—opposed the Stracittà (ultra-urban) group—centered on writers Curzio Malaparte and Massimo Bontempelli and their literary magazine Novecento: Cahiers d’Italie et d’Europe. While the latter emphasized their adherence to international literary trends and a cosmopolitan identity, the former aspired to represent the local, rural component of Fascism. Michela Rosso summarizes Strapaese values as “promotion of small-town rustic life and of the peasantry; restoration of the indigenous elements of the native culture; recourse to the proud agrarian tradition of Italy; dismissal of cultural homogeneity, foreign culture and bourgeois values as decadent and corrupt.”65 The group equated Italianness with rural identity: “We are savages,” Maccari wrote in one issue of their magazine Il selvaggio (The savage), “and we think that Italians will save themselves only if they understand and decide, once and for all, to become savages.”66

Fascist propaganda presented the countryside as a wholesome environment fostering the connection between human beings and land, thus replacing class consciousness with national sentiment. Not coincidentally, the borgate included spaces for orchards that, in the words of the architect of Primavalle, “offered significant economic and moral advantages” to the residents.67 Working-class urban identity was seen as a threat to Fascism’s interclass, nationalistic project. Fascist policies sought to prevent the working-class from living in Rome, as their presence could catalyze unpredictable reactions—precisely the kind of emergent rebellion historically nurtured by urban environments.

Sventramenti, and the move of the urban working class to the periphery of Rome, led to the “invisibility of poverty both to inner-city residents and to visitors from outside,” David Forgacs points out. As the poorest inhabitants of Rome were being pushed quite literally to the city’s geographic margins, they were also being pushed to Italy’s “social margins.”68 Fascist urbanism—designed for collective rituals that fostered publicattachment to the regime and its leadership—revitalized Rome as a political and administrative center, not as a residential and commercial area. The city became a sum of panoramic views, a stage rather than a lived space. Fascist urbanism meant to shape the city as a ceremonial site to be performed, not inhabited. In the capital, “only great voices should resonate, only great words should be uttered; and all that is small and wretched should disappear,” argued art historian Antonio Muñoz, a key figure in the most destructive urban projects enacted by Fascism.69 This is still clear in the Via della Conciliazione, as its shops mostly serve pilgrims rather than the (dwindling) permanent population. Fascist urbanism displaced the working classes from the city center but brought them back to it as part of political spectacle—but only as part of spectacle. (Fig. 16)

The regime wanted the potentially disruptive working class to not feel at home in the city. One of the aspects that interwar urbanists most decried in colore locale was how the working classes used the street as an extension of their homes, appropriating the public space to socialize in spontaneous ways. Describing the neighborhood of Macel de’ Corvi (demolished in 1902 for the construction of the Vittoriano), lawyer and Rome expert Ermanno Ponti wrote in 1931,

Here—as elsewhere—as in Monti, as in Trastevere, the populace considered the public street neither more nor less than a kind of legitimate appendix of its own house, and made it its headquarters to gather in groups and play morra [a gambling game] while the wives sitting near the doors chucked the stocking or—a solemn vision—drew the spindle to the rock. Hanging from the windows, the linens dried, while geraniums and marjoram bloomed from the sills or around the small balconies.70

Paul Baxa points out that one of the main aims of the sventramenti was to defamiliarize Rome for its former working-class residents.71 Not only did the new Fascist Rome look unfamiliar, but by forcing low-income residents to live outside the city the regime prevented them from orienting themselves in the rapidly changing landscape. The Via della Conciliazione is an example of how urban renewal was one of the regime’s key strategies to disarm class struggle by breaking the bonds between the working class and urban space.

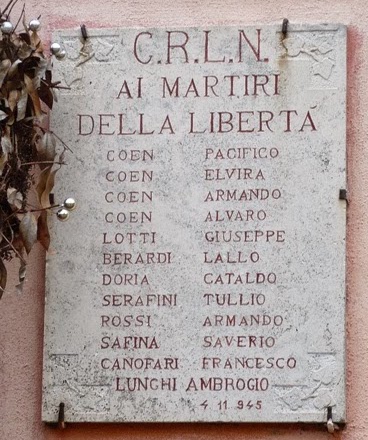

That many borgate became beacons of anti-Fascism is thus a superb irony. (Fig. 17) Even if, as Salsano and Villani have shown, there was no causal relation between sventramenti and borgate, the borgatari claimed that relation as their foundational myth. The sventramenti facilitated the creation of a cohesive narrative that brought together the urban poor, whether directly affected or not by Fascist urban transformation and the demolitions it provoked. The Fascist strategy of social control thus partially backfired. Living in spaces of homogeneous class makeup encouraged rather than hindered precisely that class identity that the regime had tried to prevent through urban dislocation.

Although the borgatari belonged neither to city or countryside, the new areas, despite the efforts of the regime, created new forms of identity.72 Fascism did succeed in reshaping the class composition of Rome’s center: the urban poor did not return as residents after Fascism’s fall. Emptied of traces of vernacular and popular activity, Rome became increasingly gentrified, and a starker separation between bourgeois and proletarian city was enforced. However, paradoxically, in the borgate the proletariat acquired a stronger class consciousness than had been possible when living in the Spina or other central quarters.

- 1 Stendhal, “Promenades dans Rome” (1829), in Voyages en Italie (Paris: Gallimard, 1973), 677. Unless otherwise indicated, all translations are mine.

- 2 Armando Schiavo, “Via della Conciliazione,” Strenna dei romanisti 15 (1990), 409–508; and Richard A. Etlin, “St. Peter’s in the Modern Era: The Paradoxical Colossus,” in St. Peter’s in the Vatican, ed. William Tronzo (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005), 270–304.

- 3 Riccardo Musatti, “La spina di San Pietro,” Il mondo,November 12, 1949, 12.

- 4 F.Z., “La piazza di San Pietro e i Borghi, Sisto X, Bernini e Napoleone I,” L’osservatore romano, November 13, 1934.

- 5 “Mussolini inaugura alcune opere pubbliche del regime in occasione del XVI annuale della marcia su Roma,” October 28, 1936, Archivio Luce newsreel, https://patrimonio.archivioluce.com/luce-web/detail/IL5000026299/2/mussolini-inaugura-alcune-opere-pubbliche-del-regime-occasione-del-xiv-annuale-della-marcia-roma.html (accessed August 31, 2020).

- 6 Richard A. Etlin, Modernism in Italian Architecture, 1890–1940 (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1991); Giorgio Ciucci, “Roma capitale imperiale,” in Storia dell’architettura italiana: Il primo Novecento, ed. Giorgio Ciucci and Giorgio Muratore (Milan: Electa, 2004); Borden W. Painter, Mussolini’s Rome: Rebuilding the Eternal City (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005); Paul Baxa, Roads and Ruins: The Symbolic Landscape of Fascist Rome (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2010); Aristotle Kallis, “‘In Miglior Tempo…’: What Fascism Did Not Build in Rome,” Journal of Modern Italian Studies, vol. 16, no. 1 (January 2011), 59–83; Aristotle Kallis, “The ‘Third Rome’ of Fascism: Demolitions and the Search for a New Urban Syntax,” The Journal of Modern History, vol. 84, no. 1 (March 1, 2012), 40–79; and Joshua Arthurs, “The Excavatory Intervention: Archaeology and the Chronopolitics of Roman Antiquity in Fascist Italy,” Journal of Modern European History, vol. 13, no. 1 (2015), 44–58.

- 7 Spiro Kostof, “The Grand Manner,” in The City Shaped: Urban Patterns and Meanings through History (Boston: Little, Brown, 1991), 209–77; Spiro Kostof, “The Popes as Planners, 1450–1650,” in A History of Architecture: Settings and Rituals, ed. Greg Castillo and Spiro Kostof (New York: Oxford University Press, 1995), 485–509; Michel Carmona, Haussmann (Paris: Fayard, 2001); Terry Kirk, “Monumental Monstrosity, Monstrous Monumentally,” Perspecta 40 (January 2008), 6–15; Patrice de Moncan, Le Paris d’Haussmann (Paris: Les Éditions du Mécène, 2012); and Dorothy Metzger Habel, “When All of Rome Was under Construction”: The Building Process in Baroque Rome (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2013).

- 8 Guido Zucconi, “Gustavo Giovannoni: A Theory and a Practice of Urban Conservation,” Change over Time, vol. 4, no. 1 (Spring 2014), 76–91; and Maria Grazia Turco, “L’Associazione Artistica fra i Cultori di Architettura a Roma: Battaglie, iniziative, proposte,” Bollettino del Centro di Studi per la Storia dell’Architettura 45–52 (2015), 165–98.

- 9 The “Governatorato” was formed in 1925 to replace the elected mayor of Rome; it was an unelected administrative body that reported directly to the central government, which appointed the “Governatore.” See Paola Salvatori, Il governatorato di Roma: L’amministrazione della capitale durante il fascismo (Milan: Franco Angeli, 2006)

- 10 Maria Luisa Neri, “Il collegamento tra le due città: L’apertura di via della Conciliazione,” in L’architettura della Basilica di San Pietro: Storia e costruzione, ed. Gianfranco Spagnesi (Rome: Bonsignori Editore, 1997), 435–44.

- 11 Mia Fuller, “Wherever You Go, There You Are: Fascist Plans for the Colonial City of Addis Ababa and the Colonizing Suburb of EUR ’42,” Journal of Contemporary History, vol. 31, no. 2 (1996), 397–418; Paolo Nicoloso, Mussolini architetto: Propaganda e paesaggio urbano nell’Italia fascista (Turin: G. Einaudi, 2008); Luca Acquarelli, “The EUR Utopia: Scenographic Views in the Service of Fascist Regime,” in Lo stile Italiano (Milan: Silvana Editoriale, 2011), 207–209; Vittorio Vidotto, Esposizione Universale Roma: Una città nuova dal fascismo agli anni ’60 (Rome: De Luca, 2015); and Vieri Quilici, EUR: Una moderna città di fondazione (Rome: De Luca, 2015).

- 12 Aristotle Kallis, “‘Reconciliation’ or ‘Conquest’?: The Opening of the Via Della Conciliazione and the Fascist Vision for the ‘Third Rome,’” in Rome: Continuing Encounters between Past and Present, ed. Dorigen Caldwell and Lesley Caldwell (Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2011), 129–51; and Paolo Nicoloso, Architetture per un’identità italiana: Progetti e opere per fare gli italiani fascisti (Udine: Gaspari, 2012), 82–88.

- 13 See, among others, Federico Chabod, “L’idea di Roma,” in Storia della politica estera italiana dal 1870 al 1896 (Bari: Laterza, 1951), 179–323; John Pollard, Money and the Rise of the Modern Papacy: Financing the Vatican, 1850–1950 (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2005); Roberto Pertici, Chiesa e stato in Italia: Dalla grande guerra al nuovo concordato (1914–1984) (Bologna: Il Mulino, 2009); and Francesco Campobello, La chiesa a processo: Il contenzioso sugli enti ecclesiastici nell’Italia liberale (Naples: Esi, 2017).

- 14 Roberto Morozzo della Rocca, “Piazza San Pietro,” in I luoghi della memoria: Simboli e miti dell’Italia unita, ed. Mario Isnenghi (Rome-Bari: Laterza, 1996), 514–23; and Terry Kirk, “Framing St. Peter’s: Urban Planning in Fascist Rome,” Art Bulletin, vol. 88, no. 4 (2006), 761.

- 15 Valter Vannelli, “La spina dei borghi dopo l’unità: Dibattiti, progetti e questione romana,” Quaderni dell’Istituto di Storia dell’Architettura 25–30 (1997), 425–34.

- 16 Spiro Kostof, The Third Rome, 1870–1950: Traffic and Glory (Berkeley: University Art Museum, 1973), 70. For their own analysis, see Marcello Piacentini and Attilio Spaccarelli, Memoria sugli studi e sui lavori per l’accesso a S. Pietro (Rome: Ti Velograf, 1944).

- 17 Studio Fotografico Vasari, “Fotomontaggi del modello del ‘nobile interrompimento,’ il porticato monumentale che, da progetto, avrebbe dovuto concludere via della Conciliazione prima dell’arrivo in piazza San Pietro,” in Archivio Storico Capitolino (Rome), V Ripartizione, Posizioni Collaudate (b.25, f. 1), 1937–38.

- 18 “Cantiere per la costruzione del modello al vero del ‘nobile interrompimento,’ il porticato progettato dagli architetti Piacentini e Spaccarelli alla fine della Via della Conciliazione,” in Istituto Luce, Cinecittà, A00079442, 1937–1938. According to Paolo Nicoloso, the pope was favorable to such separation, but the regime cancelled it. Nicoloso, Architetture per un’identità italiana, 88.

- 19 Nicoloso, Architetture per un’identità italiana, 82–88; and Aristotle A. Kallis, The Third Rome, 1922–1943: The Making of the Fascist Capital (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014), 127.

- 20 Andrew Anker, “Il Papa e Il Duce: Sixtus V’s and Mussolini’s Plans for Rome,” Journal of Urban Design, vol. 1, no. 2 (June 1996), 165–78; and Kirk, “Framing St. Peter’s,” 756–76.

- 21 Simonetta Falasca-Zamponi, Fascist Spectacle: The Aesthetics of Power in Mussolini’s Italy (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997), 10, 15.

- 22 Ibid., 25.

- 23 “Speech by Benito Mussolini on April 21st 1924, When He Was Made Honorary Citizen at the Campidoglio,” in Scritti e discorsi di Benito Mussolini, vol. 4 (Milan: Hoepli, 1934), 93.

- 24 See Diane Yvonne Ghirardo, “Città Fascista: Surveillance and Spectacle,” Journal of Contemporary History, vol. 31, no. 2 (1996), 347–72; Franck M. Mercurio, “Exhibiting Fascism: Italian Art, Architecture and Spectacle at the Chicago World’s Fair, 1933–1934” (MA thesis, Northwestern University, 2001); D. Medina Lasansky, The Renaissance Perfected: Architecture, Spectacle, and Tourism in Fascist Italy (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2004); and Maria D’Anniballe Williams, “Urban Space in Fascist Verona: Contested Grounds for Mass Spectacle, Tourism, and the Architectural Past” (PhD diss., University of Pittsburgh, 2010).

- 25 Nicoloso, Mussolini architetto.

- 26 I thank the anonymous reviewer for encouraging me to reconsider my initial position on Mafai’s canvases.

- 27 “L’insediamento del Primo Governatore di Roma,” Capitolium, vol. 1, no. 10 (1926), 596.

- 28 Emilio Gentile, Fascismo di pietra (Rome: Laterza, 2007).

- [29] Italo Insolera, Roma moderna da Napoleone I al XXI secolo (Turin: G. Einaudi, 2011), 140.

- 30 Daniele Manacorda and Renato Tamassi, Il piccone del regime (Rome: A. Curcio, 1985); and Stephen L. Dyson, “Archaeology and Urbanism in Fascist Rome,” in Archaeology, Ideology, and Urbanism in Rome from the Grand Tour to Berlusconi (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2019), 154–79.

- 31 Leonardo Benevolo, San Pietro e la città di Roma (Bari: Laterza, 2004), 40.

- 32 Carlo Magi-Spinetti, “Colore locale,” Capitolium, vol.11, no. 1 (January 1935), 23.

- 33 Giuseppe Bottai, Fronte dell’arte (Florence: Vallecchi, 1943), 59, translated in Anker, “Il Papa e Il Duce,” 165–78.

- 34 Benito Mussolini, speech to the Senate in March 1932, in Benito Mussolini, Opera omnia, vol. 25 (Florence: La Fenice, 1952), 86, translated in Kallis, The Third Rome, 115.

- 35 Antonio Cederna, Mussolini urbanista: Lo sventramento di Roma negli anni del consenso (Rome: Laterza, 1979), xxiii.

- 36 Attilio Spaccarelli and Marcello Piacentini, “Dal Ponte Elio a San Pietro,” Capitolium, vol.12, no. 1 (1937), 5–38.

- 37 Anna Cambedda, La demolizione della Spina dei Borghi (Rome: Fratelli Palombi Editori, 1990); and Maria Cecilia Mosconi, “La demolizione della Spina di Borgo nelle documentazioni fotografiche nelle cronache e nelle fonti archivistiche,” Storia dell’urbanistica, vol. 6, no. 2000/02 (2007), 156–78.

- 38 Italo Insolera and Antonio Cederna, Roma fascista nelle fotografie dell’Istituto Luce (Rome: Editori Riuniti, 2002), 197.

- 39 Cambedda, La demolizione della Spina dei Borghi, 40.

- 40 Emilio Cecchi, “Psicologia delle demolizioni,” Capitolium, vol.12, no. 1 (1937), 37.

- 41 They are analyzed in Claudio Parisi Presicce, Laura Petacco, and Anna Aletta, La Spina, dall’agro vaticano a via della Conciliazione (Rome: Gangemi Editore spa, 2016), the catalogue of an exhibition that took place in Rome’s Musei Capitolini in 2016.

- 42 Spaccarelli and Piacentini, “Dal Ponte Elio a San Pietro,” 29.

- 43 Lanfranco Maroi, “Il rione The Borgo,” Capitolium, vol. 12, no. 1 (1937), 50–51.

- 44 Spaccarelli and Piacentini, “Dal Ponte Elio a San Pietro”; and Mosconi, “La demolizione della Spina di Borgo.”

- 45 For middle-class housing as an issue for Fascist urbanism, see Maristella Casciato, “The ‘Casa All’Italiana’ and the Idea of Modern Dwelling in Fascist Italy,” Journal of Architecture, vol.5, no. 4 (2000), 335–53; and Flavia Marcello, “Fascism, Middle Class Ideals, and Holiday Villas at the 5th Milan Triennale,” Open Arts Journal 2 (winter 2013–2014), 1–21.

- 46 Fernando Salsano, “Il ventre di Roma: Trasformazione monumentale dell’area dei Fori e nascita delle borgate negli anni del governatorato fascista” (PhD diss., Università degli Studi di Roma Tor Vergata, 2009), 167.

- 47 Luciano Villani, Le Borgate del fascismo: Storia urbana, politica e sociale della periferia romana (Milan: Ledizioni, 2014), 205–48.

- 48 Augusto Moltoni quoted in Alessandro Portelli, The Order Has Been Carried Out: History, Memory, and Meaning of a Nazi Massacre in Rome (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003), 62.

- 49 On the borgate, see Giovanni Berlinguer and Piero Della Seta, Borgate di Roma, vol. 1 (Rome: Editori Riuniti, 1960); Alberto Clementi and Francesco Perego, eds., La metropoli “spontanea”—Il caso Roma (Bari: Dedalo, 1983); Insolera, Roma moderna da Napoleone I al XXI secolo; Villani, Le Borgate del fascismo; Milena Farini and Luciano Villani, Borgate romane: Storia e forma urbana (Forlì: Libria, 2017); Flavio Conia, “Le politiche abitative della Roma fascista: L’esempio della Borgata Popolarissima di Tormarancia,” Diacronie: Studi di storia contemporanea, no. 35 (2018), https://journals.openedition.org/diacronie/8925 (accessed August 31, 2020); and Andrea Greco and Paolo Petaccia, Borgate: L’utopia razional-popolare (Rome: Officina, 2016).

- 50 Insolera, Roma moderna da Napoleone I al XXI secolo, 144.

- 51 Kostof, The Third Rome, 19.

- 52 Italo Insolera, Roma moderna: Un secolo di storia urbanistica (Turin: G. Einaudi, 1962), 143.

- 53 For the influence of architectural rationalism on the borgate, see Greco and Petaccia, Borgate.

- 54 Giorgio Guidi, Piano urbanistico della nuova borgata residenziale di Primavalle: Primo nucleo di costruzioni (Rome: np., 1938).

- 55 Salsano, “Il ventre di Roma”; and Villani, Le Borgate del fascismo.

- 56 Benito Mussolini writing in Il Popolo d’Italia in 1928, in Benito Mussolini, Opera omnia, vol. 22 (Florence: La Fenice, 1957), 256.

- 57 Villani, Le Borgate del fascismo.

- 58 New York Times, March 19, 1933, V:6, quoted in Painter, Mussolini’s Rome, 94.

- 59 Pietro Ottilio Rossi, “Nascita e sviluppo della borgata di Primavalle,” Parametro 44 (1976), 36–47.

- 60 See Berlinguer and Della Seta, Borgate di Roma, 90. Emphasis in the original.

- 61 Riccardo Mariani, Città e campagna in Italia: 1917–1943 (Milan: Edizioni di Comunità, 1986).

- 62 David Atkinson, “Totalitarianism and the Street in Fascist Rome,” in Images of the Street: Planning, Identity and Control in Public Spaces, ed. Nicholas Fyfe (London: Routledge, 1998), 13–30.

- 63 For the regime’s views on urban life, see Michele Dau, Mussolini l’anticittadino: Città, società e fascismo (Rome: Castelvecchi, 2012), 29.

- 64 On Futurism’s ambiguous relation with technology and the city, see Christine Poggi, Inventing Futurism: The Art and Politics of Artificial Optimism (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2009), 1–34.

- 65 Michela Rosso, “Il Selvaggio 1926–1942: Architectural Polemics and Invective Imagery,” Architectural Histories, vol. 4, no. 1 (2016), 2.

- [66] Mino Maccari, “Idee selvagge e parole a muso duro,” Il selvaggio 3, no. 8 (1926): 21. See also Emily Braun, “Italia Barbara: Italian Primitives from Piero to Pasolini,” Journal of Modern Italian Studies, vol. 17, no. 3 (2012), 259–70.

- 67 Guidi, Piano urbanistico, 14.

- 68 David Forgacs, Italy’s Margins: Social Exclusion and Nation Formation since 1861 (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2014).

- 69 Antonio Muñoz, Campidoglio (Rome: Governatorato di Roma, 1931), 23.

- 70 Ermanno Ponti, “Roma sparita tra la Pedacchia e Macel de’ Corvi,” Capitolium, vol. 7, no. 10 (October 1931), 477–87.

- 71 Baxa, Roads and Ruins, 57.

- 72 For protests in the 1970s around housing issues, see Luciano Villani, “The Struggle for Housing in Rome: Contexts, Protagonists and Practices of a Social Urban Conflict,” in Cities Contested: Urban Politics, Heritage, and Social Movements in Italy and West Germany in the 1970s, ed. Martin Baumeister, Bruno Bonomo, and Dieter Schot (Frankfurt: Campus Verlag, 2017), 321–46.